It was some big boat, all right—a ’79 Lincoln Continental, long as a city block, blue with a white top and enough chrome to make it look like a rolling mirror. When it steamed out of Chicago’s West Side last year, there wasn’t anybody on the cracked sidewalks who didn’t figure a heavy-duty gangster was lurking inside. But, no, it was just Mark Aguirre driving over to play a little basketball at DePaul University. Naturally, people started wondering what kind of budgetary provisions the good Vincentian fathers had made for the All-American whose jump shot told the nation about their gritty, little El-stop campus.

Aguirre tried to explain that the Continental was his mother’s, that his family was better off than the public had been led to believe, that he wasn’t a flashy outlaw risking an NCAA-sponsored flogging. But the basketball program kept getting muddy tire tracks on its image, so he finally pointed the big boat back to mama’s and returned with the pearl-gray ’77 Oldsmobile 98 he still drives. As a concession to the demand for modesty, it is only half a city block long.

No matter now, though. Aguirre has another concern as he warily circles the Olds in the parking lot behind DePaul’s Alumni Hall. A dent in the right front fender is staring up at him and he is glaring back at it. “Shouldn’t never let my mother use my car,” he murmurs. “Every car I ever had, she give it a wreck first. Uh-huh, that’s what she did.”

The promise of dinner—turkey with dressing, a julienne salad without the lettuce and a couple of tall 7UPs—gets him on the road. His destination is The Seminary Restaurant, where DePaul’s training table is set nightly. When he hoofs the three blocks to dinner, he doesn’t get a chance to prove how adept he is at finding parking places for his boat, and if there is one thing Mark Aguirre likes to do when he has an audience, it is put on a show.

“How ’bout that one?”

In one instant, he is pointing across Fullerton Avenue at a space a short jump shot away from The Seminary’s side entrance. In the next instant, he is making a frantic U-turn to ace out any competition that might be heading his way from the busy intersection up ahead. As he steps on the gas, he utters a brief prayer: “Please don’t be any police around.”

There are, of course.

The cop at the wheel of the squad car motions Aguirre back across the street—on foot. His partner does the talking through an open window.

“You got a driver’s license?” he asks.

“Yeah, sure, I got one,” Aguirre replies hesitantly. “But I left it at home. I really did.”

“Is that right?”

“Yeah.”

“Okay, then tell me why you made the U-turn. You know it’s against the law to make one 100 feet from an intersection, don’t you?”

“I didn’t know nothing about no 100 feet.”

“Yeah, well, you’re supposed to take a test about rules and regulations when you get your license. That is how you got yours, isn’t it?”

Zipping up his DePaul basketball letter jacket, Aguirre laughs nervously and sits on the curb beside the squad car. Now he and the cop are face to face.

“What’s your name?” the cop asks.

“Mark.”

“Mark what?”

“Mark Aguirre.”

The cop isn’t impressed, and when he notices a man with a notebook at Aguirre’s side, his dispassion turns to scorn. “Who’s this?” he asks. “Your lawyer?”

“No, man,” Aguirre coos. “He’s a writer. He’s writing about me.”

“Yeah?”

The cop looks as though he has just found a hair on his bacon cheeseburger.

“All right,” he says, turning toward the writer and jerking a thumb back at Aguirre. “Maybe you can vouch for this guy.”

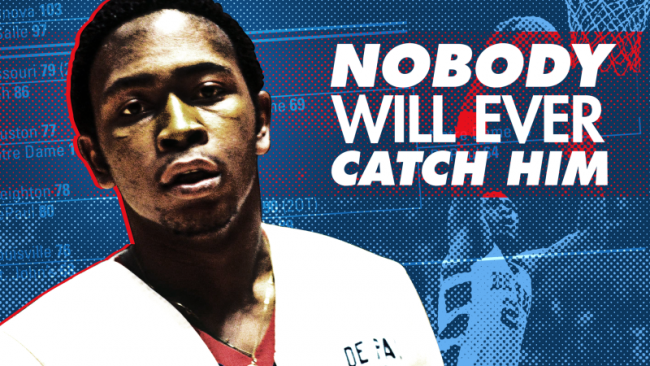

DePaul—alma mater of George Mikan, spawning ground for seemingly every City Hall fat cat in Chicago, cornerstone of a neighborhood that has gone from street-gang treacherous to rehab chic—has never seen a basketball player like Mark Aguirre.

And you can read that any way you want to.

The good way is to imagine Aguirre on the court, muscling inside with the ferocity of Adrian Dantley, then floating in jumpers from the faraway places where Dantley never treads. Dantley, Dantley, Dantley. You hear that name every time one of the National Basketball Association’s deep thinkers starts rooting around for a standard for measuring Aguirre.

It’s an understandable comparison in terms of physique as well as talent. At 6-5, Dantley of the Utah Jazz has always had to look up at the NBA’s other small forwards, and Aguirre seems destined to do the same; he was listed as 6-7 at Chicago’s Westinghouse High and DePaul does likewise, but the pro scouts project him at 6-5 1/2. Would that he could shed weight as easily as he loses inches. Unlike Dantley, who has shackled his appetite far from the nearest refrigerator, Aguirre’s caloric intake remains suspect. Even though the rigors of playing for the Olympic team last summer helped trim 24 pounds from a body that once weighed 252, no one can forget that his high school coach nicknamed him Ziggy the Elephant. God, how that reputation for flab gripes Aguirre. And yet it may have underscored his startling grace on the court. “When Mark gives you that little Julius Erving swoop,” says Pat Williams, general manager of the Philadelphia 76ers, “you forget about his bulk.”

Aguirre has been mesmerizing people one way or another since he was the 5-9, 180-pound seventh grader the other kids called Laundry Bag unless they needed two points. Then they shut up and gave him the ball. “The only reason I was around,” Aguirre says, “was because I could shoot good from the outside.” With time, a sudden surge of genetic juices and the fierce counsel of his cousin Ricky Scott—“He told me he’d never speak to me again if I didn’t keep playing”—Aguirre tied the rest of his game together with the gaudy bow now on display at DePaul.

On offense, the package looks complete. He can call on the soft 20-footer. He can take two hard dribbles and pull up with a 10-foot power jumper that bears testimony to both his strength and his accuracy. He can slant across the free throw lane, double-pump in midair and drop the ball in the basket so gently you’d think it is a snowflake. He can bull underneath, bench-press anyone who steps in his path and throw down a dunk shot. He can even lead a fast break, and will as long as he gets to dribble the ball between his legs at least once while running full speed.

There are those who suggest this is everything there is to do, but Ray Meyer, the grandfatherly taskmaster of DePaul basketball, is not among them. “Points?” he says, as though the very word offended him. “I want something besides points. When Mark has six or eight assists and 14 or 16 rebounds, then I’ll tell him he played a good game.”

The implication is obvious: Aguirre is capable of more than he gives much of the time. Much more. Dave Gavitt, his coach on the Olympic team, realized just what a special case Aguirre is after watching him loaf. “He’d be getting back on defense, going down the left side of the floor,” Gavitt says, “and he’d see his man over on the right side. Well, hell, he wasn’t going to run way over there, so he’d holler for somebody else to take his man, even if that guy had to run just as far himself. God, that made me mad. But I’ll tell you something: It takes a pretty smart player to figure that out on the fly.”

For someone whose announced goal in high school was to become a carpenter, Aguirre plays with the wisdom of a talmudic scholar. He knows what defense his team should be in; he knows when he should have the ball and when he shouldn’t; he knows because his natural instinct tells him so.

“I don’t want to give anybody any ideas,” says Joey Meyer, Ray’s son, chief assistant and heir apparent, “but Mark could coach this team.”

There is a catch, though. He would have to want to be a leader, and so far in his three years at DePaul, he has rarely shown such inclinations.

“You can tell when Mark’s not going to play,” Ray Meyer says. “If he doesn’t think the team we’re playing is any good or if he has something else on his mind, he’ll just go out there during warm-ups and fool around. And when the game starts, he won’t say anything to pick the other kids up. He could make them jump through knotholes if he wanted to, but he just worries about Mark.”

It is a tribute to the enormousness of Aguirre’s skills that the other Blue Demons pretend they don’t notice his sleepwalking routine. “If you need a bucket,” says Clyde Bradshaw, the savvy point guard, “you just automatically throw the ball in to Mark, because you know he’s going to get it for you.” Such blithe confidence is a blessing when Aguirre is primed for action and a curse when he is either uninspired or triple-teamed. The classic example of the latter was last spring when fuzzy-cheeked UCLA upset DePaul in an NCAA West Region playoff in Tempe, Arizona, and sent Aguirre running from the arena in tears. “I got my pride hurt the way it had never been hurt playing basketball,” he says. “It shook me up. It made me want to destroy UCLA when we played them again.” True to his word, he shot down the Bruins 93-77 two days after Christmas, dunking savagely, mugging relentlessly for AI McGuire and a national television audience, and pulling out a nine-month-old T-shirt bearing the words “BEAT UCLA.”

“I can wear it now,” Aguirre announced proudly.

Once again he had been vindicated. He was free to revel in his teammates’ unspoken adoration, a gift he has been receiving since he first wrapped his hands around a basketball for DePaul. He was on the baseline in Pauley Pavilion and David Greenwood, the UCLA All-American, was staring down at him imperiously, wondering what sort of trash this moon-faced freshman fatty was going to try.

Aguirre dribbled once, twice, then took off for a dunk shot that still may be ringing in Greenwood’s ears. Even Ray Meyer was impressed.

“We wound up losing by 23,” says Meyer, “and other than that dunk, we really had Mark’s hands tied the whole game. On the plane home, it all came to me. I thought, ‘My God, this kid can give me the first team we ever had that could go one-on-one with UCLA and beat them. Why not let him go?’”

Meyer had been coaching at DePaul since 1942, and never before had he surrendered to talent, mainly because he never had much talent to surrender to. The legendary Mikan? A gawky giant who spent part of his career riding the bus in from Joliet so Meyer could untangle his feet. Howie Carl? A Jewish boy who made the Catholic All-American team, but hardly a franchise. Bill Robinzine? A trumpet player who never thought of basketball in high school. Dave Corzine? An almost 7-footer who spent half his career at DePaul in outer space. And they were the top of the line.

The rest of the time, Meyer made do with kids nobody else wanted, zealous ex-seminarians and candidates for the intramural league. You learn to coach that way—to coach and plot and scheme. Meyer could do it all. He even got his Blue Demons within one game of the 1978 Final Four. But surely he must have wondered if he didn’t deserve some greater reward for his labors.

So it was that Aguirre descended on DePaul, a gift truly the result of providence. Joey Meyer was spending the winter at Westinghouse High four years ago putting the dog on a jump shooter named Eddie Johnson when he saw the glow of the future. Suddenly it didn’t matter that he would lose Johnson to the University of Illinois. Joey had struck gold in Aguirre, the pudgy junior whose feathery shooting touch blunted worries about his dining habits. What’s more, Aguirre fell in love with DePaul as soon as he realized DePaul was in love with him. Showed up at the Blue Demons’ games, watched the Blue Demons practice, spruced up his wardrobe with Blue Demon T-shirts and sweatshirts. Oh, there was a scare when Aguirre went out to visit Colorado because an assistant coach there had helped mold Adrian Dantley—that name again—in high school, but the scare was short-lived.

“The question has never been Mark the talent,” says the 76ers’ Pat Williams. “It’s always been Mark the person.”

“I wanted to play at home,” Aguirre says, “so I could get me a piece of Chicago.”

Ray Meyer realized his sincerity after Aguirre came to a game with an unholy case of the blues, then left without saying good-bye. “Nobody thought anything about it,” says Meyer, “but two days later, Mark called and apologized.” It was both a sign of how charming Aguirre can be and a warning of future funks.

One day he would be hugging the little round man he calls “Coach Ray” the way he did when they upset UCLA to make the Final Four in 1979. The next day he would be clouding up and raining on everybody, coming late to team meetings, not coming at all to pregame meals, getting bounced out of practice for overwhelming sloth, even talking back to Meyer in front of overflow crowds. Last year, when the Blue Demons were packing to move to the spacious new Rosemont Horizon and Aguirre was trying unsuccessfully to break Howie Carl’s single-game scoring record at tiny Alumni Hall, player and coach spent night after night screaming at each other and feeding bad impressions.

“The question has never been Mark the talent,” says the 76ers’ Pat Williams. “It’s always been Mark the person.”

“The people in the pros, they put that label on me and I’ll probably never get rid of it,” Aguirre said. “But I’ve changed, man. I really have. Like last year, there were some games I wasn’t ready to play. This year? No way. Sometimes I won’t take a shot for five, six minutes, but that’s not loafing on my part; I’m just trying to get my other players involved in the game. You know what I’m saying. I can play with anybody. When I reach the pro level, they’ll understand. Go ask coach.”

“I yell at Mark, sure,” Meyer says, “but I don’t treat him the same as the other boys. You can get by without the other boys, but you can’t do without Mark. He’s a superstar.”

The old coach sighs plaintively.

“I don’t know. We want to make Mark the all-around boy, but I don’t know.”

There are things that Meyer can’t control. He is dealing with one of nature’s children, and just as the right moves instinctively come to Aguirre on the floor, so do the off-court moves that perplex his elders. To them, he is almost alien at times, glowering, seldom speaking. Yet to the friends he confides in, this shell is nothing more than the natural by-product of fame. “He got to do this, he got to do that,” says Bernard Randolph, who followed him from Westinghouse High School and became DePaul’s sixth man. “Everywhere he go, he got to be Mark Aguirre.”

Nobody will ever mistake him for just another DePaul junior schlepping to school on the El, then hurrying down to Kroch’s & Brentano’s to stock the shelves with best-sellers. He is the 1980 College Player of the Year, the shooting machine who shattered Corzine’s career scoring record midway through this season. He is someone special, and being special is not without the price he has just begun to pay.

The first installment came due at DePaul last season when he fathered a daughter out of wedlock. “We have a very conservative faculty here,” says one of its more liberal members, “and when they heard that Mark wasn’t getting married, they were shocked.” But Aguirre held his ground, debating the issue in a philosophy class and declaring loudly, “I’m not ashamed of my baby.”

Erika Allen was the product of a short-term romance that perhaps was never destined for the altar, a romance that flowered amid the questionable ambience of a South Side summer basketball tournament. “Mark didn’t even want to go at first,” says DePaul guard Skip Dillard, a friend and teammate since the two of them were 12. “Only reason he went to the tournament at all was because I said there was going to be lots of girls there.” Dillard quickly tired of the available leg, but Aguirre remained until he sealed the liaison that made him a father who visits his daughter on weekends at her maternal grandparents’ home. While it doesn’t sound like much, it is more than he sees of his child’s mother.

“She’s going to nursing school right now,” he says. “In Peoria, I think it is. She just briefly told me about it.”

He stares down at the record album he is carrying.

“We’re real close,” he says softly.

The name of the album is “At Peace With Woman.”

There was never a word that Mark Aguirre’s mother was pregnant. Maybe it was because everybody had the blues 21 years ago about daddy selling the farm in Arkansas, acknowledging at last that none of his sons wanted to stay home and work those 80 acres. Maybe it was because of the excitement over the move to Chicago, daddy in his faithful pickup truck, mama and the expectant Mary on the train. Who knows?

The verifiable answers didn’t start coming in until December 10, 1959, when the three of them arrived in that strange northern city. At midday, mama called her eldest daughter, a strong-willed storekeeper who had already settled there, and said Mary was sick.

“So I took her over to Cook County Hospital,” Tiny Dinwiddie Scott says, “and that’s where Mary had little Mark.”

He weighed 8 pounds, 11 1/2 ounces and had the beginnings of the hands Ray Meyer would later compare to toilet seats. “When we got home,” Tiny recalls, “I said, ‘Lord, Mary, will you look there? Little bitty baby and big old hands like that.’”

Tiny can wax poetic on them or most anything else. “I’m a big talker,” she says proudly. But on the subject of Mark’s father, a slight postal worker named Clyde Aguirre, her expansiveness quickly shrinks. Clyde Aguirre did not stay long with his family and he is regarded now as if he never existed.

“You just have to put some spaces in there,” Tiny says.

The spaces seem bigger than ever when you realize that Mark’s mother isn’t going to fill them in for public consumption. “She’s hidden from us, she’s hidden from everybody,” says a member of the DePaul coaching staff. The response seems somehow childlike, yet it fits the way Tiny Scott thinks of Mary. “She’s my baby sister; I’m 16 years older than she is,” Tiny says. “Her, Mark, they both my children.”

Tiny’s children live in an inner-city stereotype that seems to be substantiated by the talk about Clyde Aguirre’s shadowy fatherhood and his divorce from Mary about a decade later. It all appears as predictable as the vacant lots, boarded-up windows and abandoned automobiles on the 1300 block of South Karlov Avenue, where Mark Aguirre spent the first 15 years of his life.

“Mark, he still calls me every week, he still stops by and sees me whenever he can. There’s no snobbish in him. Now that’s a miracle these days, isn’t it?”

They call the neighborhood “K Town” because of the street names—Karlov, Kedvale, Kedzie, Keeler, Kastner, Kilbourn. “It’s a jungle,” says Skip Dillard, who grew up there, too. And the jungle is ruled by the West Side’s cruelest gangs. The Four-Corner Hustlers. The Vice Lords. The Souls. They used to chase each other through the pickup basketball games at Bryant Elementary School, which sat outside Mark’s back door. They carried knives, chains, sticks, rocks. And guns. You always knew they had guns. “One time we went out to play ball,” Dillard says, “and we seen a guy that had been shot.”

“You hear bang-bang,” Tiny Scott says as she stares out the window at the emptiness across the street from her corner grocery store. “Okay, you hear, uh-huh. Where you going to run to? K Town, to me, is home. If there’s something better, I don’t know about it.”

The stereotype stops at Tiny.

It was she who encouraged her four brothers and two sisters to come north. By the time she was finished, almost the whole block was family. And the family ate dinner together after church on Sunday, helped shoulder each other’s burdens and watched out for each other’s kids. “I guess we was pretty emotional,” Mark says. “Whenever there was any kind of crisis, everybody would be there helping.”

Time brought changes. Mark, so overweight and withdrawn as a child, sprouted into the giant who worked such wonders with a basketball that gang members gathered to drink wine and watch him. His grandmother, Cora Dinwiddie, died when he was 13 and, says Aunt Tiny, “He was surely his grandma’s boy.” His mother got married again, this time to Wesley Ross, the owner of a trucking company, a man who could put her and Mark and her three daughters in a big house a couple of miles from Karlov. The old house caught fire one night and burned to the ground, leaving yet another space in K Town.

“But, you know, that Mark, he still calls me every week, he still stops by and sees me whenever he can,” Tiny says. “There’s no snobbish in him. Now that’s a miracle these days, isn’t it?”

Perhaps it is testimony to the appeal of the corner grocery store that it has no name out front and greets its customers with this felt-tip proclamation: “You must buy at least $1.00 in all meat.” Aguirre, Skip Dillard and Bernard Randolph scarcely notice the symbols of hard times, though. They are too busy taking advantage of Tiny’s family discount (translation: no charge), charming the Hostess Cakes delivery man out of a box of Twinkies and astounding Terry Cummings, the gentle muscleman who plays center for DePaul.

When Aguirre goes to wash down his share of the Twinkies with a quart of milk, Cummings proves he’s a stranger in K Town. “You’re going to drink that by yourself!” he asks.

“Sure,” Aguirre chirps merrily. “That’s the way we do things around here.”

Basketball is the No. 1 sport at DePaul University. Trying to figure out Mark Aguirre runs a close second.

He never shows anyone the same face two days in a row, and the result has been as many opinions about him as he has moods. The opinions range from the obtuse—“He’s deep and he isn’t”—to the cynical—“He’s an actor; he wants to keep you off balance so he can have his way with you.” Lately, however, there has been a tacit moratorium on the amateur psychoanalysis, primarily because in the town where you can see a man dance with his wife, you can now also see Mark Aguirre dive on the floor for a loose ball.

That,” says assistant coach Jim Molinari, “is a first.”

The first of what, though? Of the changes that will turn Aguirre into the good soldier everyone thinks he should be? In Ray Meyer’s office, with the thump-thump-thump of the handball court next door punctuating every sentence, the old coach is telling himself exactly that. “There’s no sense in saying we made him into the player he is,” Meyer says, “All we’re doing is maturing him.”

If that is indeed what is happening, Meyer’s blend of screaming and back-patting is part of the story, but not all of it. The rest is rooted in the gauntlet Aguirre has been running for the past year.

He began his long, strange trip by flirting with the same sweet temptress who will be back this spring—the NBA draft. It would have been easier on the nerves to straight-arm the agents who came around eager to do his bidding. Instead, he enlisted one Charles Tucker to serve as his middleman—not his agent, mind you; an agent would have made him a pro. Tucker, the Michigan-based psychologist who held Magic Johnson’s hand in similar circumstances the year before, screened the offers, rumors and gossip. And Aguirre listened, suffered and brooded, for no team could promise it would deliver on his dream of a five-year, $1.5 million no-cut contract.

Since the Celtics had the first pick last spring and, after failing to woo Ralph Sampson into the pros, expressed an interest in Kevin McHale, Aguirre would have been left dangling. Obviously, the Celtics were the only team with a guaranteed first-round pick. Any other franchise could have been cut off at the pass by another team which drafted ahead of it.

“I have decided,” Aguirre announced after a sleepless April night, “that I have a love for more than money.”

It may not have been the whole truth, but Aguirre had been force-fed enough reality for the time being. He realized that, as he says now, “you make yourself crazy if you wait till the last minute the way I did.” And, although he didn’t verbalize it, he seemed to understand that he had some work to do on his game and his image. “For the first time,” says Rod Thorn, general manager of the Chicago Bulls, “I think Mark figured out that the sun doesn’t rise and set on him.”

Maybe that was why he played for the U.S. Olympic team last summer. He certainly didn’t have to. Look at the ease with which Ralph Sampson of Virginia said no to the red, white and blue. “We weren’t going to Moscow,” says Dave Gavitt, the wise man from Providence who coached the Olympians, “but we were going to play a series of games against the best players from the NBA. I thought that ought to be a helluva thrill for any kid.” It was enough for Aguirre, who willingly banged heads and bodies with teammates Michael Brooks of La Salle and Danny Vranes of Utah, did his share of the rebounding and passing, and kept his mouth shut when he only played 24 minutes a game. “He did the dirty work,” Gavitt says, “and he was still the greatest talent we had.”

Only once did Aguirre act like he knew it. In Phoenix, with the NBA stars on the ropes, Gavitt’s assistant, Larry Brown of UCLA, yelled at him to shake a tailfeather on defense and Aguirre responded with a snippy “Yes, sir!”

“I yanked him right there,” Gavitt says. “Told him to clean up his act. I told him he wasn’t playing for some Catholic boys’ school in New Orleans where he could get away with that crap. Then he went back out and played like hell.”

The fire and brimstone has stayed with Aguirre this season at DePaul. After Georgetown outrebounded the Blue Demons by 19, he tore into San Diego State for eight rebounds in the first half alone. When his teammates turned to stone on offense against Maine, he boogied for 47 points, hitting eight of nine shots from the field in one stretch and leaving Ray Meyer mumbling that only seven-foot centers are supposed to dominate games that way.

It is hard to believe that in DePaul’s home opener, with Gonzaga down by 22, Aguirre was overcome by disinterest, threw away three straight passes and found himself on the bench next to Meyer engaging in acrimonious debate. The next day, Meyer kicked him out of practice for sulking while an assistant coach muttered, “He’ll always be a shitass.” A week later, they all resumed talking about how much Mark had changed for the better.

“So what are we going to do with you?” The cop is obviously enjoying a pliable audience. “Think we ought to take you to the station downtown and book you?”

“Ohhhh, man,” Aguirre says, smiling as if he isn’t sure he is being kidded.

“You broke a law, didn’t you?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, I got to do something, right?”

“Uh-huh. I guess.”

“How about this? How about you spell the word DePaul for me? You do that and you walk, huh? How about it?”

“Sure. D-e-p-a-u-l.”

“Wrong.”

Aguirre’s baffled smile suddenly reappears.

“It’s capital P. Now get out of here.”

Aguirre does as he is told, heading back across Fullerton Avenue, back toward The Seminary and some dinner. He pauses only long enough to take another look at his dented Olds, and when he does, his smile changes character, becoming strangely triumphant. “If the police seen that,” he says, pointing at a temporary license sticker that expired three weeks ago, “I would’ve gone to jail for sure.”

Mark Aguirre likes to think that nobody will ever catch him.

[Illustration by Sam Woolley/GMG]