Archibald Lee Moore, the light-heavyweight boxing champion of the world, is 44 years of age by his own account and 47 by his mother’s. She says that he was born on December 13, 1913, in Benoit, Mississippi, but he insists that the year was 1916 and, on occasion, that the place was somewhere in Missouri, or perhaps Illinois. “My mother should know, she was there,” he has conceded. “But so was I. I have given this a lot of thought, and have decided that I must have been three when I was born.” Whoever is right, Moore is the most elderly champion in the history of boxing. By all the rules of the game, he should have faded into retirement long ago, like his contemporaries Joe Louis, Joe Walcott, Ezzard Charles, and Rocky Marciano, all of whom have settled into a sedentary life appropriate to their gray hairs and accumulating paunches. Moore’s hair is gray and he is often grievously overweight, but he just doesn’t seem to age. “I don’t worry about growing old, because worrying is a disease,” he says. Not long ago, he was chatting with a friend in a Los Angeles gymnasium after a workout when he chanced to overhear a couple of young fighters discussing him. “That old man should quit,” said one of the apprentices, nodding toward Moore. “He should get out and let us take over. Look at him with his old gray head!” Moore walked lightly over to where the two fighters were standing, and said, smiling, “It isn’t this old gray head that worries you young fellows, it’s this old gray fist.”

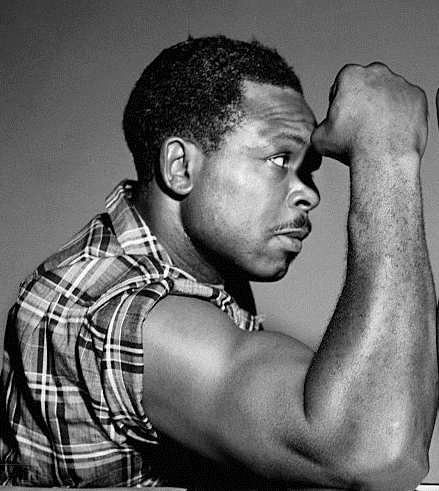

Moore has been a professional boxer for twenty-six years, starting as a middleweight, winning his championship as a light-heavyweight in 1952, by beating Joey Maxim in 15 rounds, and on two occasions fighting for the heavyweight title—first, in 1955, against Rocky Marciano, and then, in 1956, against Floyd Patterson, both of whom knocked him out. He has had 214 fights to date, and won 183, 131 of them by knockout—a record unmatched in pugilism. However, because his build is undistinguished and countenance unscarred, there is nothing about his appearance that hints at the violent nature of his trade, and he affects a wispy bebop goatee that gives more the look of a jazz musician than of a fighter. His taste in wearing apparel is something less than severe—he usually goes into the ring draped in a gold or silver silk dressing gown festooned with sequins, and he has been photographed at Epsom Downs in England wearing a gray topper, striped pants, and a cutaway, and on Fifth Avenue strolling along, cane in hand, in a white dinner jacket and Bermuda shorts—but his natural poise and his almost regal bearing enable him to carry off such trappings with dignity. Moore calls himself “the Mongoose,” but although he is sharp-sighted and agile and fearless, like a mongoose, he has practically none of the irritable nature of that ferocious little animal. Moore’s warm personality and rough-and-ready wit make friends for him everywhere. People come up to him on the street to shake his hand, and motorists wave to him. He can go unannounced into a nightclub in Harlem or its Los Angeles counterpart and soon the management will have him on the bandstand, entertaining the customers with his light patter. Children respond to him enthusiastically. “Wouldn’t it be awful if a man had to go through a day—even one day—without a little music and laughter?” he once said when somebody complimented him on his happy disposition.

Moore is probably the most widely traveled boxer of all time—largely because there was a period of some years when it was impossible for him to get fights in this country with anyone near his class—and he is proud of the attention he has received from Toronto to Tasmania. “I have passed the time of day with President Eisenhower and, if you will pardon me, several dictators,” he remarked some time ago. “I was once criticized for some newspaper pictures showing Juan Perón with his arms around me. I can only reply that when the head of a government invites me to meet him, I think it is judicious to do so. I have been in Germany, too. I posed with all the West German politicians, policemen, generals, and fighters. When I ran out of dignitaries I went to the parks and posed with the statues. I really dig that historic stuff, you know. However, I am not a political person. I am an ambassador of good will.”

In actuality, Moore isn’t quite the political innocent he often pretends to be. He is a registered Democrat and, as a San Diego resident of some 20 years’ standing, has worked on behalf of several California office seekers. Moreover, in 1960, he ran for a lame-duck term as assemblyman in California’s 79th Assembly District, but he was beaten, probably because he didn’t bother to train—a tendency that he had carried over from his professional life. (Instead of campaigning for the office, Moore went off to Rome and rounded up a suitable challenger for his championship—an Italian fighter named Giulio Rinaldi, who outpointed him in a non-title bout.) When Moore took out his nominating papers, he listed Mississippi as his birthplace on one affidavit and Missouri on another. Advised that he’d have to make a choice, he protested, on the ground that both states deserved this honor. Eventually he decided in favor of Mississippi. (In Nat Fleischer’s The Ring, though, he is quoted as having said he was born in Collinsville, Illinois.) He also listed his occupation as “the light-heavyweight champion of the world,” but a deputy registrar pointed out that California law permits only a three-word description on the ballot, so he reluctantly settled for “light-heavyweight champion.”

“I think I’ve made a definite contribution to boxing; if everybody is going to forget that, why, I’ll get a job or go into the movies or something.”

If the deputy registrar had chosen to make a point of It, he might have questioned that capsule description as well, for although Moore is the recognized champion where it counts—in New York, Massachusetts, and California, and abroad—the National Boxing Association, which presides over the small-time, or remaining 47 states, decided late last year that he was not defending his championship often enough and declared the title vacant. Moore, who has had a running feud with the National Boxing Association for years, appealed to the United Nations. It hadn’t previously occurred to anybody that the United Nations had jurisdiction over boxing, but when Moore’s camp sent a telegram to Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge asking him to help a “great internationalist,” the NBA backed up and granted Moore an additional period of grace in which to contract for a championship fight. Moore paid no heed. “When I wanted the NBA to recognize me as a challenger, they let me wither for five solid years,” he said. “I think I’ve made a definite contribution to boxing; if everybody is going to forget that, why, I’ll get a job or go into the movies or something.” When the deadline was up, the NBA defrocked Moore a second time and arranged for a fight between the two leading contenders—Jesse Bowdry, a 23-year-old St. Louis fighter, and Harold Johnson, whom Moore had fought five times and defeated four times, the last fight being a championship bout at Madison Square Garden in 1954, when Moore knocked him out in 14 rounds. Johnson knocked out Bowdry in nine rounds, and the NBA said he was champion. The fact remains that Moore is in the big money and Johnson is not.

Johnson currently declares that he is no longer interested in fighting Moore. “Archie is an old man, and they can put you in jail for beating up old men,” he said not long ago. “Why, Johnson is my protégé,” Moore countered. “I have always looked after Harold and said nice things about him. The trouble with Harold is that he is under the impression the clock of time has stopped. As soon as the young man”—Johnson is 33—”makes a reputation for himself, I’ll be glad to give him another shot at my title.” At various times, Moore has announced that he intends to keep his championship for 16 years, or until 1968 (“That would help me get even for the 16 years I waited until they finally let me fight Maxim”), and that he will continue to defend his title until he can pass it along to his son, Hardy Lee. Hardy Lee recently observed his first birthday.

Moore loves to talk. “I am a great sidewalk talker,” he once said. “I can talk Mexican-fashion, squatting on my heels, or big-city style, with my spine up against a lamppost or a building, or even garment-center technique, with my backside at the edge of a curb.” He is a frequent after-dinner speaker, and he plans his post-fight speeches, which are usually addressed to a nationwide radio and television audience, with loving care. “When I am invited to speak at a prison, I usually accept, because nobody walks out in the middle of my speech, and there is no heckling,” he says. Moore sometimes talks while he is fighting, too. In 1957, when he knocked out Tony Anthony in the seventh round of a championship fight in Los Angeles, Anthony’s manager Ernie Braca, complained that his man had been befuddled by Moore’s line of chatter. “Archie is a smart old guy,” he said. “He talked his way to victory.” “Please remind Mr. Braca that I mixed a few punches into the conversation,” Moore responded.

Moore acknowledges certain defects in his conversation. “I’d rather use six little words than one big one,” he says. “I tend to draw a pitch out. I say this to say that. Eventually, however, my meaning comes clear. Like the night I was fighting Bobo Olson. I hit him in the belly with a left hook and followed with a right to the head. The right was slightly high, but Bobo got the message. Still, there is, I fear, that one chink in my armor. I am inclined to waste words. In fact, I throw them away. It is my only excess.” The last statement is not entirely accurate. Moore has such a tremendous fondness for food that he regularly eats himself out of shape—so far out that every time he has defended his championship he has been obliged to take off from 25 to 40 pounds in order to reach 175 pounds, the weight limit of his class. The sports columnist Jimmy Cannon once accused him of gluttony, to which he replied, with all possible solemnity, “No, Jimmy, I am not a glutton—I am an explorer of food.” According to his associates, the difficulty is that he chooses the wrong terrain to explore, and Moore himself admits that “the things I like to eat are not becoming to a fighter.” He is particularly attracted to starches and to fried foods, and between meals he finds an icebox irresistible. Some months ago, when he was in New York with his lawyer on business, the two men shared a hotel room, and one night, a couple of hours after they had retired, following a seven-course dinner, the lawyer, awakened by a stealthy noise in the room, turned on the light just in time to see Moore walking in his sleep through the door. Leaping out of bed, the attorney grabbed him by an arm and steered him back into the room. “Archie! What are you doing?” he demanded. Moore mumbled sleepily, “Where is the icebox in this house?” He then awakened, ate a bagel he had bought that evening from a street vender, and slept quietly until it was time for breakfast.

Although Moore contends that “fat is just a three-letter word that was invented to confuse people,” his battles with the scales have often provided more excitement and suspense than the ring battles they prefaced. He always waits until the last possible minute to start reducing. “In order to lose weight, I’m must get myself into the proper frame of mind,” he once said when he was facing such an ordeal. “I’m circling the problem now, looking it over carefully. I may pounce at any time.” When Moore pounces, the mongoose in him comes out. He believes in trimming down the hard way, by means of a low-calorie diet and savage exercise—a combination that would almost certainly hospitalize a lesser man—and the regimen makes him snappish. In the summer of 1955, while Moore was training for his championship fight with Bobo Olson at the Polo Grounds, he took off 23 pounds, the last few at Ehsan’s Training Camp, a dreary, unpainted sweat pit in Summit, New Jersey. His trainers closed the doors and windows of the gymnasium early every afternoon, quickly transforming it into a steam cabinet, and in this suffocating atmosphere Moore, swaddled in a skintight rubber costume, went through his ritual of shadowboxing, sparring, bag-punching, and rope-skipping, giving off sprays of water like a revolving lawn sprinkler. The close air was almost unbearable, but he drove himself furiously, and during the last 24 hours before the weigh-in had nothing to eat or drink except half a lemon. The method seemed extreme, particularly for a middle-aged athlete, but it was effective. Moore made the weight by two pounds and knocked out Olson in three rounds.

“You can eat as much as you like, as long as you don’t swallow it.”

Last May, when Moore started training for his most recent title defense—on June 10, at Madison Square Garden, against Rinaldi, the man who had outpointed him in a non-title match in Rome the year before—he weighed 198 pounds. For the Rome fight, Moore had agreed to weigh in at a maximum of 185 pounds or forfeit a thousand dollars. He started taking off surplus weight, mostly in steam cabinets, only six days before the match, and the best he could do was a hundred and ninety, so he lost the thousand. Furthermore, Rinaldi took the decision. For the New York match with Rinaldi, when the title was at stake Moore diminished himself with such a desperate crash diet (“You can eat as much as you like, as long as you don’t swallow it,” he was fond of saying at the time) that the fight crowd began speculating on whether he would have enough strength left to mount the steps into the ring. Rocky Marciano, who visited Moore’s training camp, called Kutsher’s in the Catskills, was appalled by his training methods. “I don’t believe Rinaldi can lose the fight,” he said. “The weight-making will beat Archie—that’s the big thing.” The promoters of the bout, alarmed by the possibility that the star would either collapse from exhaustion or be disqualified by excess poundage, invited the alter champion, Harold Johnson, to serve as a standby. “Hasn’t Harold always stood by?” Moore asked when be was told about it. Moore made the weight by half a pound, and Dr. Alexander Schiff, who examined him for the New York State Athletic Commission, marveled at his condition. “I don’t know his age, but he has the body and reflexes of a man of 30 or 32,” the doctor said. A great sigh of relief was heard from Harry Markson, general manager of boxing for Madison Square Garden. “I feel as though I had lost that weight myself,” he said, beaming. Johnson was not surprised. “I knew he’d make it,” he said. “Archie wasn’t going to let me have all that money.” Moore won an overwhelming 15-round decision, and seemed as fresh at the finish as he had at the start. Fascinated by this time with the whole subject of weight removal, he issued an invitation to newspapermen: “Come to my home town a year from now and you won’t find a fat man in San Diego. I’m going to open a chain of health studios.” He hasn’t got around to it yet, but at last report he was still thinking about it.

A self-styled expert on nutrition, Moore frequently speaks of a “secret diet” that he says he obtained from an Australian aborigine in the course of his travels. (“Did you ever see a fat aborigine?” he asks.) He declares that he got the diet in exchange for a red turtleneck sweater, and he regarded it as a professional secret up until last year, when he included it in his autobiography, The Archie Moore Story, written in collaboration with Bob Condon and Dave Gregg, and published by McGraw-Hill. The diet proved to be about like most other diets, except that it placed uncommon emphasis on the drinking of hot sauerkraut juice for breakfast—an idea that the aborigine had somehow overlooked. Unfortunately, the appearance of the diet coincided with the embarrassing disclosure that Moore was asking postponement of a fight with Erich Schöeppner, a German light-heavyweight, because he was unable to make the weight.

Moore’s alternating periods of feast and famine subject his physique to such drastic restyling that he finds it convenient to buy clothes in three sizes. There’s one rack of suits for the heavyweight Moore, at around 215 pounds; another for the junior-heavyweight Moore, at 190; and still another for the championship weight. Moore tends to regard his smallest self as something of a stranger. Studying his profile in a mirror before one of his title fights, he said critically, “I look sort of, funny, when I get down to 175. I’m not skinny, exactly, but I don’t look like me.”

Once a fight is over, it doesn’t take long for Moore to become recognizable to himself again. When he is in residence in San Diego, he likes to entertain his friends with cookouts at which the staple item is barbecued spareribs, and when he is fooling around at his rural fight camp, a small ranch situated on a ridge of rocky but oak-shaded hills 30 miles northeast of San Diego, and known as the Salt Mine, he often takes a skillet in hand and fries up a tasty batch of chicken, which is one of his favorite dishes. “Fried chicken has a personality of its own,” he says. “You can eat it hot or cold, with a fork or free-hand style.” As a matter of fact, Moore’s home, a two-story brick house on the edge of downtown San Diego, was built on the site of a restaurant that he owned and operated for a number of years and that was called the Chicken Shack. Under his personal supervision, the house has been remodeled and expanded, at a reported cost of $150,000, until it has become one of the showplaces of the city. The creature comforts include a swimming pool in the shape of a boxing glove; a poolside cabana that is equipped, fittingly, with both a barbecue pit and a steam room; a soundproof music studio where he plays a piano or a bass fiddle in occasional jam sessions, or listens to an extensive collection of jazz records; and three rumpus rooms—one for himself, one for his wife, and one for his children. In his rumpus room, Moore has a regulation-size pool table, imported from England. “I play piano, but will shoot pool with tone deaf guests,” he says. “After all, a man can’t spend his whole life just fightin’ ‘n’ fiddlin’.”

“Fried chicken has a personality of its own,” he says. “You can eat it hot or cold, with a fork or free-hand style.”

He is also an expert pistol shot (he practices frequently on targets at the Salt Mine), a skilled angler, a student of boxing history, and a handyman who is equally at ease with an electric drill or behind the steering levers of a bulldozer. “The main secret of true relation is diversion,” he says. “A person who has no hobby has no life.” He is devoted to the current Mrs. Moore—the former Joan Hardy—a tall, attractive, light-complexioned woman, who has borne him two daughters and two sons in six years of marriage. Because she is a sister-in-law of the actor Sidney Poitier, she is not much awed by her husband’s celebrity, and she cheerfully makes allowances for artistic temperament. She didn’t complain, for example, when Moore insisted that she shorten the heels on her shoes by a full inch. He is 5 feet 11 inches tall, and she is only an inch less. The champion didn’t want his wife towering over him, and he refused to wear elevator shoes. Since he wouldn’t go up, she agreed to come down. (When Moore first sprouted his goatee, along with a light mustache, a reporter asked him if his wife didn’t object to the new growth when he kissed her. Moore smiled indulgently and replied, “A girl doesn’t mind going through a little bush to get to a picnic.”) Mrs. Moore—she is his fifth wife—has been a stabilizing influence on her husband. Not only has she given him domestic happiness but her quiet efficiency has brought a measure of order to his once disorganized social and business affairs. Until she assigned herself the duties of secretary, bookkeeper, and business manager, Moore was surrounded by clutter and chaos. Well-meaning but irresponsible, he would accept half a dozen speaking engagements for the same date and ignore them all. Now his appointments are cleared through his wife, and he usually shows up on schedule.

Mrs. Moore is also secretary of Archie Moore Enterprises, Inc., a firm that was established two years ago for the purpose of supervising the champion’s investments and maintaining amicable relations with the Director of Internal Revenue. Moore is the president of the corporation; the vice president is Bill Yale, a young San Diego attorney; and the treasurer is Clarence Newby: a San Bernardino CPA who serves as Moore’s accountant and tax expert. The president’s income from boxing and related activities goes to the corporation, which pays him a salary. Moore doesn’t like to talk about his financial affairs. “I am wealthy in terms of happiness, because I have a wonderful wife and fine children,” he says, “but I still must scratch for a living.”

Moore’s professional entourage, whose members wear uniform blue coveralls as they go about their various duties at the Salt Mine, includes an odd assortment of friends. There is, for instance, Redd Foxx, a sort of court jester, whose admiration for Moore is so extravagant that he once had his hair barbered to form the letter “M.” There is a wizened little man in his late seventies known as Poppa Dee (his real name is Harry Johnson) whom Moore calls “the medicine man of boxing.” “I like to have Poppa in my camp because he makes me feel good,” Moore says. Then, there is a sparring partner called Greatest Crawford, who has made a substantial reputation in the ring on his own hook, and a masseur called Big Bopper (his real name is Richard Fullylove), who stands 6-foot-2 and weighs 298, and who used to play football for a small Negro college in Texas. At one time, Moore planned to farm him out between fights to the San Diego Chargers, of the American Football League, but the Big Bopper was unable to pass the Charger physical examination. He had high blood pressure.

Moore has had three trainers in recent years—Cheerful Norman, Hiawatha Grey, and the incumbent, Dick Saddler. Cheerful Norman left the Moore entourage five years ago, and Hiawatha has quit several times after minor disputes with Moore, but the two men remain firm friends. Hiawatha, like Archie’s other trainers, and like Archie himself, is a Negro. “He is a very wise old owl,” Moore has commented. “It would be wise to be married to him 14 years before you call him Hiawatha, because he doesn’t like the name. Most people just call him Hi. He goes his own way.” Saddler has been the most enduring of Moore’s trainers, and his staying power can probably be attributed as much to a happy nature and a talent for playing the piano as to his technical qualifications. Moore’s authority is unquestioned when he’s in training, but Saddler’s clowning relaxes him, and when he’s relaxed, he willingly takes orders. (Nevertheless, Moore insists on taping his own hands before a workout or a fight—he is the only pugilist of stature to do so—and won’t wear protective headgear while sparring in the gymnasium, lest he come to depend on it.) When Moore is skipping rope, a routine that invariably attracts a crowd at training headquarters, Saddler accompanies him on the piano, usually pounding out a boogie-woogie beat. “My only trouble with Dick is that he is a ham,” says Moore. “He tries to upstage me. I put the piano behind a curtain, but he insists on being seen.” Saddler is satisfied with the relationship. “I guess Archie hired me because I can play piano,” he says, “but he admits I know a little about fighting, too.” Another long-time friend and camp follower is Norman Henry, a drowsy sort of man who is always welcome at the Salt Mine, even though he is a fight manager and fight managers, collectively, are anathema to Moore. Moore simply enjoys his company. One afternoon when Henry was catnapping in a chair, Moore nodded toward him and remarked to a visitor, “At the dawn of civilization there were three men. One, watching lightning strike, saw the possibilities of fire. Another invented the wheel. Norman? Well, Norman was asleep. He had already invented the bed.”

Last winter, Moore’s Salt Mine sparring partners included a handsome young boxer out of Dallas named Buddy Turman, who a short time later turned up as Moore’s opponent in a ten-round non-title bout in Manila. (Fighting one’s sparring partners, it should be explained, is an old and cherished custom in the fight game. Rocky Marciano fought a series of harmless exhibitions with one of his relatives a few years ago, and Young Stribling, a fighter of an earlier era, was—until Moore deposed him—the all-time knockout champion, thanks in no small measure to his custom of flattening his chauffeur in one small town after another.) Moore usually has two or three rookie fighters on tap at his training camp, and for a brief period the cast included a distinguished young man named Cassius Marcellus Clay, who, having made a reputation by winning the Olympic light-heavyweight championship in Rome the summer before last, had decided to learn what he could at the feet of the Master. Accompanied by a woman lawyer, Clay flew to San Diego last fall and announced that since he planned to turn professional, he was going to spend at least a month studying under Archie Moore at the Salt Mine. Clay said he admired the Mongoose more than any other fighter in the world and would gladly do anything asked of him—that no sacrifice would be too great, no chore too mean or small. He devoutly hoped that Moore would become his manager. It sounded like an ideal arrangement, but within two weeks Clay had turned in his blue coveralls and left, saying, “I wanted Archie to teach me to fight, but the only thing l learned was how to wash dishes. Whoever heard of a fighter with dishpan hands?” Clay is now fighting under other management and remains unbeaten after eight bouts. He is considered a long-range threat to Patterson.

It was at the age of 15 that Moore determined to become a fighter. His color was chiefly responsible for this decision, because boxing was the only way he could see for a Negro to rise above the kind of poverty he grew up in. He was born Archie Lee Wright, but his parents were separated shortly after his birth, and he and his sister, Rachel, and his half-brothers, Louis and Jackie, were all brought up in a St. Louis slum by his Uncle Cleveland and his Aunt Willie Moore, whose surname he adopted as a convenience. His uncle died when Archie was 14, leaving only a small insurance policy, and it was up to Aunt Willie to support the family. “We had a tie of affection in our home—oh, it was so beautiful,” Moore recalls fondly. “As they say, we were too poor to paint and too proud to whitewash, so we kept everything spotless. We had bare wood floors, and on Saturdays we scrubbed them with lye soap. We kept our house so clean it was like a hospital. My auntie taught us that we might not have the best furniture or wear the best clothing, but we sure could keep them clean.” Despite the best Aunt Willie could do to bring them up properly, however, both Archie and Louis had brushes with the law in their teens (as Moore recalled in his autobiography, “Louis was light-fingered by nature, and somehow a man’s watch got tangled up in his hand, and the man sent the police to ask Louis what time it was.”), and Archie spent a 22 month term in the Missouri reformatory at Booneville for hooking coins from a streetcar motorman. Of the reformatory experience, he says, “I don’t say I enjoyed it, but I’m grateful for what it did for me. It was a glorious thing in my life, because it forced me to get eight to ten hours of sleep every night; it gave me an opportunity to have three hot meals a day; it gave me a lesson in discipline I would never have got at home. They used to pay me a little something for the work I did, but it should have been the other way around. I should have paid them for what they did for me.”

“I began to read in the newspapers about the boxers. Kid Chocolate was my first hero. I suppose I liked him because his name sounded so sweet. His skin was ebony; he was like patent leather. Most of all, the money intrigued me.”

Shortly after Archie returned home from Booneville, he and his aunt had a conference about his future. “I had thought about what I could do, and I told my auntie I wanted to fight. For a Negro starting a career, that was the only way. It was the last road. I considered the other possibilities. I could get an education and become a postman or a teacher; I could become a policeman or fireman; I could play baseball. There weren’t many opportunities then, even for an educated Negro. As a teacher, the most I could become was a school principal. As a policeman, I couldn’t advance beyond the rank of lieutenant or captain. I couldn’t be a police chief or a fire chief; my color made that impossible. Professional baseball didn’t offer much, because at that time all the colored ball players were in Negro leagues, and Satchel Paige was the only one of them who was making big money. He had a reputation and his big drawing power, so he took a percentage of the gate. The other colored ball players were lucky to earn $300 a month. Remember, this was right in the middle of the depression. I began to read in the newspapers about the boxers. Kid Chocolate was my first hero. I suppose I liked him because his name sounded so sweet. His skin was ebony; he was like patent leather. Most of all, the money intrigued me. I read that Kid Chocolate was fighting for a gate of $10,000, and that seemed like all the money in the world. I knew Kid Chocolate got 25 percent of the purse. According to my figures, that was around $2,500, and he was a rich man. Twenty-five hundred dollars! Do you know what kind of money that was then? Do you know how much it was to a family that depended on the government for a basket of food each week—for a family that waited for a government check each month to pay the rent? It was fabulous. It was my way out.”

It is unlikely that any fighter has ever put more thought and effort into learning the boxing trade than Moore. He was skinny as a boy, but he developed unusual strength with exercises of his own invention. One of his stunts was walking on his hands. He’d go up and down stairs on his hands, and sometimes around the block, or around several blocks. The boy also developed his arms and shoulders by exercising phenomenally on a chinning bar. While still in his teens, he once chinned himself 255 times, and he used to shadowbox hour after hour in front of a mirror. “The idea was to take myself out of Archie and put me into my image,” he says. “I tried to visualize what I would do to Archie if I were the fellow in the mirror. I wanted to anticipate the reaction to my moves. I learned boxing from beginning to end and from end to beginning.” To develop his jab, he got the idea of practicing before a mirror with a five-pound weight in each hand. He would wrap his fists around a pair of his Aunt Willie’s flatirons and spar for six minutes without a rest. Then he’d pause for breath and repeat the procedure. “I knew I’d be wearing six-ounce gloves in the ring,” he explains. “If I could spar with five-pound weights, the six-ounce gloves would feel as light as feathers. I’d never have to worry about becoming arm-weary.” He credits his stinging jab to the flatirons. “I had the best jab in the business, Joe Louis notwithstanding,” he says proudly.

In the course of events, Moore went to work in one of the Civilian Conservation Corps camps, at Poplar Bluff, Missouri, and there had a chance to take part in the Golden Gloves competitions, which gave him excellent training. After a while, he was fighting and winning what are known in the trade as “bootleg fights,” in which technically amateur fighters make a little side money fighting anybody they can get a match with. One of the earliest such bouts he remembers was with Bill Simms, at Poplar Bluff, in 1935. Moore knocked him out in two rounds. This sort of campaigning—in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Illinois—kept him on the go, and he was learning fast. “When I was fighting as an amateur, I used to ride the freight trains, and once I had an experience I’ll never forget,” Moore recalls. “I was on a freight returning to St. Louis when a brakeman got after me. I had been standing there on the side of a tank car—it had molasses in it, I think—and I was daydreaming, without a care in the world, when a sixth sense told me I was in danger. I pulled back just as the brakeman swung at me with a club. He missed, and the club splintered on the handrail of the car. It would have killed me sure if he had hit me. I was scared and excited, but I got away from him. I ran. I was as sure-footed as a goat. I’ve always wondered why that fellow wanted to kill me. I was just a harmless hobo. I wasn’t bothering anybody. I suppose that brakeman will never know the grief he caused me. When he swung that club, I dropped the little bag I was carrying. I lost all my fighting equipment. I had a pair of nice white trunks, a pair of freshly shined shoes, and my socks all neatly rolled. Those things meant a lot to me, and I was heartbroken over losing them.”

Moore’s first professional fight, to the best of his recollection, was against Murray Allen, in 1946, in Quincy, Illinois, and he won a decision, breaking his right hand in the process. His share of the gate was three dollars, which was two dollars less than the sum required for a boxing license. (“The commission was very generous,” says Moore. “When they told me that I’d have to take out the license, they agreed to waive the other two dollars. I didn’t fight in that state again until 1951. By then, I guess the license had expired.”) The newspapers and the record books had not yet deigned to take notice of young Archie Moore, but before the year was out he had begun to establish himself. According to the latest edition of The Ring, Moore won 13 fights in a row that year, all by knockouts, and then lost the next three by decisions and won the seventeenth, by a decision. The first of the recorded knockouts was over Kneibert Davidson. The following year, 1937, he fought a dozen times and won the middleweight championships of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Missouri, all 12 bouts by knockout.

Early in 1938, Moore headed for California, where he hoped to establish himself by fighting the prominent middleweights of the day—Bandit Romero, Eddie Booker, Swede Berglund, and others. He was riding in an automobile driven by a St. Louis mechanic named Felix Thurman, who was his manager at the time, when, near Bartlesville, Oklahoma, a car in the opposite lane suddenly bore down upon them. Thurman had a split-second choice—meet the other car head on or pile into an irrigation ditch. He chose the ditch. The car flipped over and landed on its roof, knocking Thurman unconscious. Moore, unharmed but frightened, tried to pry open a door, but it wouldn’t budge. Then he heard the sound of dripping liquid. It was water dribbling from the upturned wheels, but Moore thought it was gasoline, and was afraid the car would catch fire. In a panic, he smashed a window with his right fist, and then crawled out through the jagged glass, cutting an artery in his right wrist. Unaware that the cut was bleeding badly, he made a desperate effort to lift his unconscious companion from the wreckage, but he couldn’t, so he stood beside the road, helpless and bewildered, until a car came along—carrying, as luck would have it, two interns. They quickly administered first aid to Moore and revived Thurman, who was not seriously injured. “Do you know how long you would have lived with the blood spurting like that?” one of the interns asked Moore. “About 14 minutes!” Moore still speaks with awe about the kindness of the two men who saved his life. “It was almost too much for me to understand,” he said some years later. “I figured that anybody in Oklahoma seeing two Negroes overturned in a ditch would drive on. Yet the first car stopped and came to my aid. I don’t know whether God is a white man or a black man, but I knew then He truly made us all.”

Fortunately, the automobile, once it had been turned right side up and towed to a filling station, proved to be still navigable. Thurman straightened the dented top with a mallet he had brought along in his tool chest, and the two resumed their journey. The tow job had cost them $12, leaving them with a capital of $23, and this was reduced by $5 the next day, when Thurman developed a toothache and was obliged to go to a dentist and have a tooth pulled. When they ran out of money completely, Thurman began trading his expensive mechanic’s tools for gasoline, yielding his treasures piece by piece. A spray gun got them their last tank of gasoline, and they arrived in La Jolla, where Thurman’s wife had preceded them, at three o’clock in the morning, weary and hungry, having driven several hundred miles and eaten only a sack of peanuts and two oranges in the past 24 hours. Moore, always an early riser, awoke at 6:30 and went for a pre-breakfast sprint along the beach, in the course of which he noticed a great column of smoke arising from the direction of nearby San Diego. He wondered idly where the fire was, and later that morning, when he and Thurman called on a San Diego boxing promoter named Linn Platner, he learned that it was at the Coliseum. The aspiring young fighter had arrived in San Diego on the day the boxing arena burned down.

For the next several years, Moore moved around a great deal but moved upward in the boxing world only a little. He toured Australia and Tasmania and came off very well, winning four of his seven fights there by knockout and the others by decision, but when he returned to this country, there still seemed to be no place for him in the big time. Not long ago, Moore was asked whether he thought racial bias had kept him out, and he said, “I would rather believe it didn’t. In fact, I would be making excuses for myself if I blamed my troubles on color. Joe Louis, Henry Armstrong, and John Henry Lewis were Negroes, and they all won championships during that period. Racial prejudice couldn’t have been the main reason. My problem was that the people who handled me didn’t have good enough connections. Looking back, though, I’m glad that’s the way it was. The people who handled me did not deliver me to the element that controlled boxing. I don’t want to talk about that element. I’m just happy I never came under the control of those people. I’m not saying, mind you, that I have any affection for fight managers. If it weren’t for managers, a lot of fighters would have been millionaires. I have emancipated myself from the pit of boxing, and I am no longer tied down by managers.” Moore was particularly aggrieved, it seems, because the last manager to hold his contract—Charlie Johnston, with whom he parted company in July of 1958—insisted on doing some of the talking for the firm. “Charlie was the sort who always wanted to speak for his tiger,” Moore says. “But he didn’t bother to call when our contract ended; he knew better. I have finally earned the right to meet the press and public the way a fighter should.” Not long ago, Moore outlined a plan for turning his ranch into a haven for aged and indigent managers. “Every day, I would come in with a blacksnake whip and get them up. Then I’d have them do five miles of roadwork around the ranch. That would be good for their health and also give them a chance to understand their fighters a little better. But I wouldn’t be altogether harsh. I’d furnish them with cheap cigars, and give them plenty of time to lie and boast to each other. Of course, I’d have a small problem remembering all their names because most fight managers look alike to me. But I’d overcome that. I’d have a common name for them—Bum. That’s what they spend their lives calling the kids they live off.”

Moore’s current manager, Jack (Doc) Kearns has the official title of “boxing representative,” because the champion can’t stand the word “manager”. A veteran of the boxing world, Kearns gives his age as 69, though 80 is probably closer to the mark. He has been part of Moore’s life since Moore won the championship from Maxim, in 1952. Maxim was then managed by Kearns, and Moore had to guarantee Maxim $100,000 for the fight. This gave Moore a clear idea of the value of the championship and of the value of Kearns, and when the title changed hands, Kearns came along with the franchise. Moore, who received only $800 for winning the championship, not only adopted Kearns but adopted his policy of demanding $100,000 guarantee for putting his title at stake. The only contract between him and Kearns is a handshake. “I cut my purses with Doc because I like him,” says Moore. “Doc is for his fighter. He made my big matches with Olson, Marciano, and Patterson. We’ve had a fine relationship. Doc is a promoter, a talker, a guy who knows how to maneuver. You could give Doc 200 pounds of steel wool and he’d knit you a stove.”

In 1941, Moore was industriously beating his way through thickets of contenders on his way to the middleweight title, and had achieved the eminence of fifth rank in that division, when, in March, he collapsed on the sidewalk in San Diego and was taken unconscious to a hospital. His illness was diagnosed as a perforated ulcer, and an emergency operation was necessary to save his life. The newspapers reported that if Moore survived, which seemed doubtful, he would never fight again. He was in the hospital 38 days, and spent an even longer period convalescing, and then came down with appendicitis, which necessitated another operation. Then, late in the summer, gaunt and wasted, he appeared in the office of Milt Kraft, who at the time was overseer of a government housing project that was about to get under way in San Diego, and asked for work as an unskilled laborer.

“When Archie came to see me, he was so weak he could barely stand,” says Kraft, who now owns a wholesale sporting goods business in San Diego. “Three different kids who were working for me put in a word for him, separately. They all said he was sickly but a good worker. ‘Don’t worry about this guy—we’ll see that his work gets done,’ they said, but I didn’t want it that way. If I hired a man, he had to be able to do a job, to pull his own load. Archie obviously wasn’t in shape for heavy work, but I decided to find something for him. You don’t turn away a man when three people speak up for him. When that happens, the fellow is pretty sure to be something special. I had an opening for a night watchman and I offered the job to Archie. We had a big trailer camp where the workers were going to live, and about 550 empty trailers to look after. I gave Archie a key to one of the trailers, and told him to lie down and rest. I asked only one thing—he’d have to get out every hour during the night and check the trailer area.” ‘I’ll do anything,’ he said. ‘I’m desperate.’” Moore had been on the job about a week when Kraft began receiving reports of strange activity in the trailer camp. People in the neighborhood complained of a phantom runner in the night, and, investigating, Kraft found Moore jogging along among the trailers as he made his rounds. “My association with Archie was the most inspiring experience of my life,” Kraft says. “I’ve never seen a man with such determination. Here was Archie, down on his luck, a physical wreck, the doctors telling him he would never fight again, yet he was positive in his own mind that he’d become a champion.”

Kraft and Moore soon became firm friends, and the fighter got into the habit of reporting early for work each evening. “Archie came early because he wanted to talk,” says Kraft. “He told me about himself and he wanted to know about me. Somebody told him I had won the national bait-and-fly-casting championship in 1939, and he began examining me like a trial lawyer. He had to know everything about me. He asked me if I had been confident before the tournament, if I had been sure I was going to win. He wanted to know at what point I became sure of myself, whether I had been afraid or excited. I told him I had been very confident, and positive that I would finish high among the leaders. That made his eyes shine. He told me, ‘Mr. Kraft, I feel exactly the same way. I’m absolutely certain I’ll be champion of the world someday.’”

Many years later, after Moore had indeed become champion of the world, the two men went fishing on the Colorado River, in California. It was the first time Moore had ever held a casting rod. Kraft showed him how to grip it and where to throw the plug. “When he reeled it in, he had two bass, weighing two pounds apiece,” Kraft says, smiling happily at the memory. “Imagine catching two bass with one cast the first time you wet a hook! A man who can do that can do anything.”

Moore, disqualified for military service because of his two operations, returned to the ring early in 1942, and won his first five fights by knockout, but it was not until 11 years and 54 knockouts later that he got a chance at a world’s title, and by this time he was officially a light-heavyweight and was occasionally taking on heavyweights. He met Maxim, the light-heavyweight champion, in St. Louis on December 7, 1952, won a decisive victory on points, pocketed his $800, and shook hands with Doc Kearns. Prosperity was just around the corner. During the next 19 months, he won 13 fights, including two more with Maxim, and he was just beginning to get his share of the big money when, in the course of a routine physical examination for the California Athletic Commission before a scheduled bout with Frankie Daniels, in San Diego, in April, it was discovered that something was wrong with Moore’s heart. The boxing world was stunned. The Daniels fight, which was called off, was to have been a warm-up for a bout at Las Vegas between Moore and Nino Valdes, who was then the No. 2 ranked heavyweight. Moore was ordered to bed in a San Diego hospital, and the diagnosis was confirmed by a heart specialist. The doctors held out little hope. Moore’s heart ailment was organic; he would never fight again, and he would have to forfeit his championship. Friends who visited him in the hospital at the time found him close to despair. “This is so cruel,” he said, clenching his fists in anguish. “I’ve been fighting all these years and I’ve never made any real money. Now I’ve got a chance to cash in, and this happens.” He turned away, rolling on his side to face the wall. For the first time that anybody could remember, he seemed defeated.

Doc Kearns was the only person who didn’t lose courage. With nothing to go on but faith in his fighter (the title “Doc” was conferred on him by Jack Dempsey, and not by a medical school), he convinced himself that Moore’s heart condition was correctable. At any rate, he was certainly not going to accept the judgment of two local doctors as final. He obtained Moore’s release from the San Diego hospital and flew with him to San Francisco to consult another specialist. The verdict there was the same: Moore had a heart murmur, and fighting was out of the question. Then Kearns, Moore, and a friend named Bob Reese—an automobile dealer from Toledo, Ohio—took off for Chicago, where they went to Arch Ward, sports editor of the Chicago Tribune, for advice. Ward himself, as they knew, was receiving treatment for a heart ailment, and he recommended that they see the Chicago specialist who was treating him. Once more the news was bad: Moore dare not fight; no commission would license him. Ward, who later died of a heart attack, wrote a column urging Archie to retire. Then Moore and Kearns decided to go to the Ford Hospital, in Detroit, for an examination by Dr. John Keyes, of the cardiology department. “Detroit was our last hope,” Kearns recalls. “I’d been told that they had the greatest heart doctors in the world at the Ford Hospital. If they couldn’t help Archie, I knew he was finished.” Dr. Keyes’ findings brought the sun up again for Moore and Kearns. The heart condition wasn’t organic, after all; Moore had a fibrillation—an irregular heart rhythm that was correctable with medication. “They put me to bed, and I began receiving medication every two hours,” Moore says. “This continued for four days. On the fifth day, I had another electrocardiogram, and the heartbeat was regular again. The doctor gave me a clean bill of health, and I got my walking papers.”

For all Moore’s popularity with the sports writers and with other students of boxing, who were aware of his artistry from his early days, the public regarded him as just another good fighter, though one with a flair for publicity,

A month and a half later, on May 2, 1955, Moore fought Valdes as scheduled, in the Las Vegas ball park. Many of Moore’s friends thought that he was foolish to fight so soon after recovering from a heart ailment, and some sports columnists were ghoulishly speculating that he might die in the ring; they warned the Nevada State Athletic Commission against assuming responsibility for the bout. Sports writers arriving in Las Vegas a couple of days before the fight found Moore exercising before a paying audience in a ballroom above the Silver Slipper gambling casino. He looked terrible. Free to enter the ring at whatever his weight happened to be on the day of the fight, he had allowed himself to balloon to 200 pounds, and he was in such poor shape that he had difficulty lasting three minutes with a sparring partner. He spat out his mouthpiece after 30 seconds in the ring because he could barely get his breath.

The fight itself was scheduled for 15 rounds. When it began, Valdes was as trim as a panther, and Moore looked like the winner of a pie-eating contest. Silhouetted against the evening sky, he shuffled about the ring, his long trunks flopping in the breeze. He landed a few blows and was clearly exerting himself as little as possible. The crowd began to jeer him, and Valdes steadily piled up a lead on points. Then, starting in the eighth round, the old man suddenly became the aggressor. He began scoring with his left hook, he jolted the Cuban with right hand leads, and now and then he banged Valdes with stinging combinations. It became obvious that Moore was using the bout as a training fight—that this was merely the first step in his preparations for bigger bouts later in the year, with Olson and Marciano. As the contest progressed, Moore became stronger and Valdes faded. There were scattered boos when the referee, Jim Braddock, who was the only official, awarded the decision to Moore, but most of the working press at ringside agreed with Braddock.

Seven weeks later and 25 pounds lighter, Moore defended his light-heavyweight championship against Olson at the Polo Grounds, and knocked him out in three rounds. In September, back up to 188 pounds, Moore attempted to take the heavyweight title away from Rocky Marciano, at the Yankee Stadium, and succeeded in flooring him with a short right uppercut in the second round, but Marciano got up and pounded Moore down and out in the ninth. (A year or so later, the two were reminiscing about the fight, and Marciano said, “When you had me down in the second round there, Archie, it was too close.” Moore replied graciously, “Rocky, it’s like I’ve always said—it was a pleasure to fight you.”) Marciano never fought again. The next spring—in April, 1956—he announced his retirement from the ring, and on November 30th of the same year Moore and Floyd Patterson, who had been adjudged the ranking contenders, met in the Chicago Stadium for the vacant title. Moore’s best fighting weight is between 182 and 185 pounds, but he came into the ring at 196 pounds, looking like a Buddha in boxing gloves. He was 39 (or 42) years old. Patterson, at a trim 182¼ and 21 years old, knocked him out in the fifth round with a looping left hook that Moore, normally an extremely clever defensive fighter, should have avoided easily. It was probably the worst performance of Moore’s career, but when the writers trooped into his dressing room after the fight, he received them with his customary aplomb. Instead of sulking, he stood on a bench and courteously answered questions during a long interview, but his lame explanation that he was overtrained obviously failed to satisfy the critics. Nevertheless, when the inquisition finally ended, he thanked the writers for their time and their company. “God bless you, Archie, you’re wonderful!” shouted the late Caswell Adams, then boxing writer for the New York Journal-American. Boxing writers are a cynical breed and seldom applaud anybody, but this time they cheered.

For all Moore’s popularity with the sports writers and with other students of boxing, who were aware of his artistry from his early days, the public regarded him as just another good colored fighter, though one with a flair for publicity, up until three years ago. He was suspected of being something of a fraud—a glib con man who, incidentally, could punch. Then after 22 years of struggling for recognition, he suddenly became a celebrity. The transformation came on the night of December 10, 1958, in Montreal, when Moore was pitted against a brawling 29-year-old Canadian fisherman named Yvon Durelle. For the official weighing-in ceremonies at the Montreal Forum, Moore showed up wearing a homburg and a midnight-blue shawl-collared tuxedo, and carrying a silver-headed cane. The fight mob was transfixed. “I’m only trying to give boxing a touch of class,” Moore explained. “Why, Durelle, there, is dressed like a farmer!” Moore got his deserts a short time later, when Durelle nearly slaughtered him in the first round. He knocked Moore down three times then and once more in the fifth, but Moore somehow weathered the merciless beating, outlasted his younger opponent, and, in the eleventh round, battered him unconscious. It was as wild and savage a spectacle as anything that has been seen in the television era of boxing, and it did more for the Mongoose than any other victory or combination of victories in his long, improbable career. For the first time, he had earned the respect, affection, and sympathy of the public. Instead of a personification of bravado and bluster, the public saw a resourceful and cunning fighter of surpassing grace and skill, a man of fierce pride, a man with a special kind of valor. There was a certain majesty about him, and when the end finally came, and Moore’s hand was raised in tribute to the hundred and twenty-seventh knockout of his career, the emotion of the crowd was so powerful as to be almost overwhelming.

When Moore crashed to the canvas for the third time in the first round, no one would have blamed him if he had called it a night. Instead, he recalls, he regarded himself with cool detachment (“I asked myself, ‘Can this be me? Is this really happening to me?’”) and set about redeeming himself. He got through the first round largely on instinct, and from then on he fought with all the guile and mastery he had acquired through the years. At the end of the fifth round, when he had been knocked sprawling a fourth time, Doc Kearns wouldn’t let him sit down but told him to stand there in his corner and wave to his wife in the audience. Moore couldn’t see her, but he waved anyway, and Durelle, across the ring, thought Moore was waving at him, disdainfully. It took the heart out of Durelle, and from then on Moore was in charge. Durelle wilted completely in the eleventh round, and as referee Jack Sharkey stood over him, completing the count of 10, Moore, according to Doc Kearns, was calling to the prostrate challenger, “Please get up, Yvon! I got up for you!”

All in all, it was probably the most violent and taxing night of Moore’s life, but when they put a microphone before him and trained in the television cameras, he sounded as though he had been taking tea with the Governor-General. “I enjoyed the fight very much,” he said. “I am happy everybody was satisfied with it.” Later in the evening, when the furor in the dressing room had quieted, Archie behaved like an actor on opening night, waiting impatiently for the early editions. “Was it a good action show?” he asked a friend who had dropped in. Assured that it had been the hit of the season, he said, “I’m glad I gave them a good show. At my age and at this stage of the game, I just had to win!”

In 1959, largely as a result of his astonishing rally against Durelle, Moore was voted the boxing world’s equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize—the Edward J. Neil Memorial Trophy as the fighter of the year—and on the occasion of its presentation he was given the full treatment as a newly arrived celebrity. The ceremony, which took place in the course of a banquet at the Waldorf-Astoria, was, of course, one of the grander moments of his life. When Moore got up to accept his award, instead of going directly into his speech he looked out into the banquet audience and requested permission to make an introduction. Then he asked Durelle to rise. “It takes two to make a fight,” he said. Until then, few of the guests had realized that Durelle was in the room. From this time on, Moore was in great demand at public functions, and as the banquet season progressed, his account of the Montreal fight became increasingly entertaining. He would describe in rich and dramatic detail for his various audiences the thoughts that passed through his mind while Sharkey was counting over him. As he elaborated on this fascinating theme, it often seemed that he must have been on the floor for hours instead of seconds. One version began, “I was lying there and I said to myself, ‘This is no place to be resting. I’d better get up and get with it.’ Every time I looked up, I looked into Sharkey’s face. I got tired of looking at that man.” Another version featured his eldest daughter, Rena, then just over a year old. “When Durelle knocked me down the first time,” Archie related, “I had a peculiar idea. I remembered that I had left my baby, Rena, on the bed at the hotel. She was wearing red pajamas. I was dazed by the punch, and I got the idea that if I didn’t get up somebody was going to take those red pajamas away from her. I loved to see Rena in those red pajamas, and I didn’t want anybody taking them away. So l got up.”

The American Broadcasting Company sent Moore an unedited film of the famous evening, complete with commercials and curtain speech, and one evening Moore, in a darkened room at the Salt Mine, watched it for the first time, with immense enjoyment. As he saw himself on the canvas after the first knockdown, a pathetic figure groping in a shadowy world as he desperately tried to regain his balance, Moore jeered, “Look at the poor guy. He can’t even find the floor.” When Durelle dropped him for the third time, Moore seemed faintly amused. He watched himself clutching at the ropes and trying to get up before Sharkey’s count reached 10. “Now he’s so dazed he can’t even find the ropes,” said Moore, with a soft chuckle. When the lights went up, however, he seemed thoughtful. “That guy belted me so hard he knocked out my bridge,” he said. “And my elbow was sore where I fell on it. Being hit like that isn’t much fun. It won’t happen again—not if I can help it.”

The two fighters met again in August of 1959, and Moore knocked Durelle out in three rounds. The champion is a great one for putting away an opponent as soon as the opportunity presents itself. “In this game, you have to be a finisher,” he says. “I call it ‘finishing,’ and you don’t learn it in Miss Hewitt’s school for young ladies.”

Moore is acutely aware of his special position as a champion—and, more particularly, as a Negro champion. “A Negro champion feels he stands for more than just a title,” he says gravely. “He is a symbol of achievement and dignity, and it is tough to be a loser and let down a whole race.” In 1959, not long after the Durelle fight, Sam Goldwyn, Jr., invited Moore to try out for the role of Jim, the runaway slave, in a movie version of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Both Moore and his wife were leery of what they called “handkerchief-head parts,” and a Negro publication cautioned him against taking an “Uncle Tom” role, but he proceeded with the screen test, was offered the part, and signed a contract with Goldwyn. Moore is unconscionably proud of the fact that he won the role in competition with professional actors as well as amateurs. (Among the latter was Sugar Ray Robinson, who was then the middleweight boxing champion. “Ray lost the part because he was too sleek,” said Archie. “They didn’t have sleek slaves in those days.”) Moore has boasted about how, although he was training for a title fight at the time, he memorized a 16-page script for his screen test and went before the cameras after only one rehearsal. The way he tells it, his performance in the test alone entitled him to an Oscar. At the end of the scene, as he recalls it, the professionals on the set—electricians, stagehands, and the like—broke into spontaneous applause. “Tears came from the director’s eyes,” says Archie. “Goldwyn was dabbing his eyes and shaking his head in wonder. An electrician told me it was only the second time in 30 years that he had seen such emotion during a test.” However accurate these recollections may be, the director of the movie, Michael Curtiz, appears to agree with Moore’s own estimate of his talent. “Archie has instinctive acting ability,” said Curtiz. “He seems to know just the right inflection to give a line, and his facial expressions are marvelous.”

“You are a young man, Mr. Goldwyn, and times are changing. How could I play this part when it would cause my people to drop their heads in shame in a theater?”

When Moore first saw the script of the movie, he noted that the offensive word “nigger” appeared in it now and again, but he said nothing about this until the part was his and the contract signed. Then he began maneuvering. “I’m not a clever man, but I know how to get things done,” he said later. “The script used the word ‘nigger’ at least nine times. I went through it with a pencil and struck out the word everywhere I found it. Then I took it up with Mr. Goldwyn. I told him I couldn’t play the part unless he would agree to the deletions. I told him, ‘You are a young man, Mr. Goldwyn, and times are changing. How could I play this part when it would cause my people to drop their heads in shame in a theater?’ Goldwyn thought about it and he agreed with me. He ordered the deletions. The man who wrote the script was furious; his anger meant nothing to me. I had saved my people from embarrassment.” (Actually, the word was used only once in the movie, and then when Moore was off camera.)

During the filming of the picture, Moore’s career was the subject of a program in the television series This Is Your Life, broadcast from a studio in Burbank. Since surprising the honored biographee is the cream of this show’s jest, Moore was not told what was in store for him but was whisked away from the Huckleberry Finn set with the explanation that he was needed at Burbank for some publicity shots. He had grown a stubble beard for the part, and, being vain about his appearance, he was momentarily thrown off stride when he realized that he was being seen on television screens all over the country in this woefully unbarbered condition. By the time some of his cronies got a chance to tease him about it, though, he had recovered his aplomb, and retorted, “Us slaves can’t afford razor blades.”

Moore the character actor became quite a lion at Hollywood cocktail parties during this period, and on one occasion a determined actress shouldered her way through a swarm of publicity men, actors’ representatives, and newspaper people surrounding him and demanded his attention. “Archie, there’s something I must know, and I must have an honest answer,” she declared in a compelling voice. “What was your greatest thrill—getting a starring role in Huck Finn or winning the championship?”

Moore seemed surprised. “Why, it was winning the championship, of course.”

The woman persisted, “But you’re an actor now, remember that.”

“I am a fighter,” he said softly. “A fighter first, last, and always.”

Publicity still from “Huckleberry Finn” (1960). Moore with Eddie Hodges.

After the whole Hollywood episode was over, an old friend asked him why—aside from the monetary reward, which was far from negligible—he had got so wound up in the part of Jim. “I wanted to prove that I could act without losing any dignity,” he said. “I don’t agree with those who say the role belittled the Negro. Slavery was a fact at the time; there’s no escaping that. Jim had something to say that was important even for today. He was a man searching for freedom. This man Jim is really every man who is trying to be free. Jim is spiritually free, but he yearns to be free physically, so he can buy his wife and his two children out of slavery. Every man wants to be free in a different way. Jim is just one in the long history of man’s struggles to be free.”

For all his eloquence about Jim, Moore has seldom made an issue of his color, and, unlike baseball’s Jackie Robinson, say, has not been known as a supporter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and allied causes. For this reason, many of his admirers were surprised when, seizing the microphone after his Madison Square Garden victory over Rinaldi, he used the prize ring as a platform for endorsing both the NAACP and the Freedom Riders. He announced, with some 19,000,000 people listening, that he was donating $1,000 of his purse to the Freedom Riders, another $1,000 to the United Fund in San Diego, and a $500 lifetime membership to B’nai B’rith, and was also purchasing a $500 lifetime membership in the NAACP. Certain fight fans, particularly in the South, wondered where he had got the idea, and whether he had been coached. A man who has known Moore for a long time asked him later on whether the incident had simply been an impulse of the moment. “I wouldn’t be telling the truth if I said it was an impulse,” Moore replied. “I’d thought about it. This has been brewing inside me for a long time. I knew what I wanted to do. Of course, I always rough out my speech before a fight, because I always anticipate victory.” He smiled. Then he was asked whether the idea had been his own. “Nobody puts words in my mouth!” he said sharply. With less heat, he added, “Let me tell you how I feel about this. As a colored champion, I have a responsibility to my race. I have a minor voice. So long as I have popularity, I can make my voice heard, though that isn’t always enough. Joe Louis had great popularity, but he wasn’t articulate. Some of my white friends were surprised when I spoke out, because they know I am not a militant man—they know I am not militant outside the ring. But they know the depth of my feelings. I read something not long ago that expresses what I believe. The writer said, ‘He who would deny one person freedom does not himself deserve freedom.’ I believe that. I knew I would vex certain people, but it didn’t matter. In my own way, I will do whatever I can that is right, because right will always stand.”

Some years ago, Moore and one of his numerous newspaper friends were returning to San Diego together after watching an afternoon boxing card in the bull ring at nearby Tijuana, Mexico. They had gone to the fights separately, and met there by chance, whereupon Moore had insisted on driving his friend back to San Diego in his Cadillac. The newspaperman soon noticed that Moore was strangely moody and subdued. They drove for several miles in silence, and then Moore remarked, “A fellow called me a nigger today.”

Startled, his companion kept quiet and waited for Moore to continue. “I heard there was some property for sale near the Salt Mine, and a friend drove me over to take a look,” he said. “We were driving around the property, looking for the owner, when we saw a watchman coming toward us. We waited. The watchman wanted to know what we were doing on private property. Trying to break the ice, my friend said to the watchman ‘Archie Moore lives around here; do you know him?’ The watchman said, ‘Oh, yeah, I know him; he’s just another nigger to me.’ My friend was shocked. I’ve had my place, the Salt Mine, in that area for quite a while, and he figured everybody knew me. I think he was afraid I might jump out of the car and shake that fellow, or something. Then he said to the watchman, “I’ve got a man here I want you to meet—this is Archie Moore.’ The fellow gulped. I mean I could see him gulp. I sat there and looked at him. Here was a man who looked like he was past 60; he had lived all his life with no respect for a Negro. I wondered how a man could be so ignorant. The watchman recognized me, and then he was trembling. He said, ‘If you wanted to, I guess you could get out of that car and knock me down.’ I didn’t want to hit him. I felt compassion for him. I told him, ‘No, I don’t want to hurt you; I wouldn’t waste my time. I just feel sorry for you, Mister. I offer you my sympathy.’”

The long left hook that knocked out Archie Moore for the sixth time in his career and made Floyd Patterson the heavyweight champion of the world was photographed by movie and television and newspaper cameras from almost every conceivable angle. Patterson had clearly put the last ounce of his enormous punching power into the blow, and it stretched Moore out flat on the canvas. It seemed impossible to the crowd that he could get up before the count of 10, but he did—at nine—only to go down again under a flurry of punches. He struggled to his feet a second time but referee Frank Sikora, convinced that Moore was through, stopped the fight.

As the days went on, gossip began to arise in the boxing world to the effect that Moore had taken a dive. Not long ago, a visitor to Moore’s home in asked him about it. They were sitting over a pot of coffee in his rumpus room where Moore had been writing letters—mostly to newspapermen, with whom he carries on a steady correspondence. (He takes particular pleasure in composing letters to Red Smith, the Herald Tribune sports columnist, but for reasons known only to himself he always addresses them “Mr. Red Smith care of Mr. Al Buck, New York Post,” Al Buck being another sports columnist.) Stationery and envelopes were scattered about the floor, the smooth organ music of Jimmy Smith was emerging softly from Moore’s hi-fi set, and the Big Bopper, the resident sparring partner of the moment, was dozing in a chair at the far end of the room. Moore poured a cup of coffee for his guest before replying. “It was one of the worst beatings of my life, but it was on the level,” he said. “I didn’t dump the fight. I strongly resent all this whispering, too. It’s been said I took a dive because I had bet on Floyd. Well, it takes at least two to make a bet. If the man I bet with will come forward, I will be glad to meet him for the first time. If I had beaten Patterson, I would have been both the heavyweight and the light-heavyweight champion. Don’t you suppose I could make more money with the title than by selling out in one fight? Forget my pride for a moment and look at this objectively. The odds weren’t right for a gambling coup. I was a 6-to-5 favorite. The odds didn’t change. If you rule out money, what other reason would there be for me to take a dive? I lost that fight because I was being harassed by a Cleveland woman at the time and I was upset. I lost because I got ready too soon. If the fight had been held three days earlier, I would have been the champion. The worst mistake a fighter can make is to come along too fast.”

The talk turned to the Valdes fight, and Moore was asked how long he thought he could get away with, in effect, using men as dangerous as that for sparring partners. Moore reflected a moment, and then replied obliquely. “They wonder how an old fighter like me can keep going,” he said. “The secret, my friend, is experience. I learned many things in my youth, and these are the things I have going for me now. Naturally, I fought Valdes with a plan. I’ve always had an uncanny sense of pace. In all my years as a fighter, I’ve been forced out of my pace only twice. The first time was in 1940, when I was fighting Shorty Hogue in San Diego. I had banged him up pretty fierce, and a kind referee would have stopped it. I thought he was hurt real bad and I got careless; I abandoned my plan of action and tried to finish him. He caught me with a sucker punch, then he rallied in the last two rounds, and they gave him the decision. Marciano was the other fighter who forced me out of my pace. He was so strong, so difficult to hurt. I hit him with punches that would have knocked out any other fighter, but he kept on coming. I wanted to box, but I had to slug it out to keep him from killing me. They asked me if Marciano was the greatest fighter I ever met, and I don’t know how to reply. I don’t want to seem ungenerous—but it is well to remember that I was 38 when I boxed Marciano.”

Moore went on to say that, pound for pound, Henry Armstrong, the former welterweight champion, was the best fighter he had ever seen in the flesh, but that the boxer he most admired was the late Jack Johnson, who held the heavyweight championship from 1908 until 1915. Moore had recently seen a film of the 1909 fight between Johnson and Stanley Ketchel, which ended in a 12th-round knockout by his hero. “Johnson knocked out Ketchel as easily as I would toss a ball out a window, he said. “Believe me, he would be something in these days and times. Johnson loved to punish a man; he got a great pleasure from it. He was a counterpuncher, and he got the most out of a minimum of effort. He was a master of the art of self-defense, and there have been very few masters.”

In due course, the conversation got around to the current crop of fighters, and it developed that Moore has his own way of estimating their worth. According to him, there are old-old fighters, old-young fighters, and old fighters who stay young forever. It isn’t hard to imagine where Moore fits himself into this scheme. He described Ingemar Johansson, the Swedish heavyweight, as a 10-year fighter. (This was after Johansson had won the heavyweight title from Patterson and then lost it in a rematch.) “The Swede is a 10-year fighter, but that takes in his entire career, including his amateur fights,” said Moore. He was reminded that Johansson had already been fighting 10 years. “Yes I know,” Moore said. Since there has been talk of a fight between Moore and Johansson, possibly in Goteborg, Sweden, and possibly in Philadelphia, Moore’s guest said he’d been wondering if Johansson could make much trouble for him. “No, I’m afraid not,” said Moore. “The Mongoose knows too much.”

His guest asked Moore how he expects to be remembered by boxing historians, and the thought seemed to excite the champion. He said he wanted to make a statement, and wanted it taken down verbatim. This is what he dictated: “After 26 years, it is more and more apparent there never has been a perfect fighter and there never will be. It might be said in years to come that there was the Will-o’-the-Wisp—meaning Willie Pep. There was the Saccharinated—meaning Ray Robinson. There was the magnificent Benny Leonard and Joe Gans, before our time. The Wisp, the Sweet One, they both have the marks and have suffered the wounds of the club fighter. More especially, Sweet Raymond has undergone several facial liftings and eyebrow archings. But there are still some of the writers who want to be identified with this era who swear by the beard of the false prophet that these were the only two gladiators. Meanwhile the Merry Mongoose, after more than 213 battles, fighting men in their time who were rated and qualified practitioners of the art of boxing, have suffered no more hurts than wounded feelings and only a quarter-inch scar between the eyebrows by being anxious to see what damage, if any, he had done to Floyd Patterson, by looking up suddenly and then incurring a butt—this is the only mark Moore has garnered in 26 years of boxing. Will-o’-the-Wisp, Sugary One—ring immortals? Poppycock—you can have them!” Moore got up and paced the floor for a few moments, and the Big Bopper stirred in his slumber. Then the Mongoose’s mood changed, and he was off on a lecture about “breathology” and “escapeology.” “Very few fighters know how to breathe properly nowadays,” he said earnestly. “Breathology is an art I mastered many years ago, and it still serves me well. It served me very well in my second fight with Willi Besmanoff. I didn’t get him until the tenth, but I got him. The punch that did it was something quite special. You may have thought it was just an overhand right, but that punch was delivered at a 90-degree angle and it had 500 pounds of pressure per square inch. It traveled eight inches and had enough pressure to drop a Missouri mule. I bent his horn and got his undivided attention! Now, against Rinaldi, I used the technique of Applied Muscular Tension. By feinting and moving according to a predetermined plan, I exhausted the Italian from muscular tension. I myself was unaffected by muscular tension, because my moves were calculatedly relaxed—oily and easy. It’s all in knowing the art of escapeology. Some of the boxing writers were critical of Rinaldi because he was as awkward as an amateur, punching wildly and without any plan. All that could be part of the cleverness of Moore. Please keep in mind that even the great Marciano missed me 39 consecutive times, though he finally caught up with me, aided and abetted by the law of averages.”

The hour was late, and Moore’s guest stood up to leave, but Moore detained him long enough to say, “One of these days, the law of averages, or maybe the law of gravity, will catch up with me. I can’t last forever. I’ve been thinking about how I want to go. I want to be respected. When I’m finished, I want people to say only one thing of me. I want them to say, ‘There goes a man.’” At the door, he added, “When I retire, I’m going to write a book in my own hand, and the last chapter will be entitled ‘The Prolonged Sunset.’ I’ve been looking at the sun for a long time, but it still hangs there on the horizon. When it goes down, it will go all of a sudden.”

[Featured Illustration: Jim Cooke; Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons]