A summer storm cell breaks, purplish and powerful, over the North Park Baptist Church on the north side of Orlando. Hard rain drums speedy and loud off the rusted tin portico of the recreation center, the bright little gym that Pastor Harry Bush calls “a little beam from God.” It is the kind of place where basketball is born in the hearts of the people who play it. Shorn of numbers, salaries and reputations, they come to places like this to bring the game at one another, testing at the roots the fundamental authenticity of basketball’s rewards.

The Orlando Magic have begun to filter into town, one or two at a time, as the season approaches. For a moment, several of them sit, and they listen to Pastor Bush, who talks to them of gifts and of God through the steady thrum of rain on the windows. They are veterans, most of them: big Stanley Roberts, soon to be the central player in a three-way trade that will send him to the Los Angeles Clippers; Dennis Scott, a gifted deep shooter trying to come back from a bad knee injury, and Scott Skiles, a 28-year-old guard with a sweet instinct for the game’s geometry and a go-to-hell attitude that makes him, weight for age, perhaps the toughest player in the National Basketball Association. They politely pay attention to Pastor Bush, all of them looking like men in a rescue mission out of the 1930s, willing to accept a sermon as the price for a bowl of soup.

“Some of you have come here without families,” Pastor Bush is saying. “Some of you have come down here without pastors.”

The youngest of them is also the biggest. Even sitting down, he is perceptibly taller and wider than the older players. When he was a young boy, growing up in Newark first, then on Army posts around the world, Shaquille O’Neal was ashamed of his size. He shot up to 6-foot-8 as a sophomore in high school, but his coordination lagged behind. He slouched, making himself look even more ridiculous. “My parents told me to be proud,” he recalls. “But I wasn’t. I wanted to be normal.”

He first wanted to be a dancer on the television show Fame. He wanted to be lithe and smooth and lightly airborne, working on his break dancing until he could make himself appear to flow. He spun on his head, the way the sharpest breakers did. Until, one summer, he got too wide to flow and too big to spin on his head. He had outgrown his dreams. He was 14 years old.

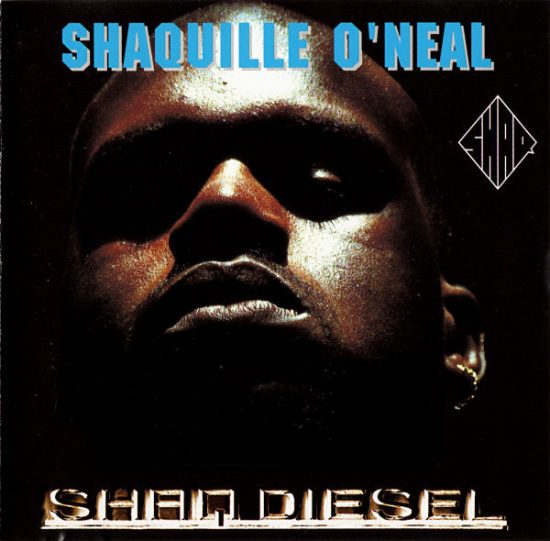

He picked up a basketball because that is what the biggest children do. At age 16, he was the most sought-after high-school player in the country, enrolling at Louisiana State University. Last spring, he became the No. 1 pick in the NBA draft, signing in August with the Magic for an estimated $40 million over the next seven years. In addition, he took the first steps toward being a multinational corporation—wholly owned by himself. Reebok, the athletic shoe company, has made him central to its drive to dominate that lucrative market. Soda companies have come calling. He also will have his own basketball and his own action figures.

The Magic is depending upon Shaquille O’Neal to reverse its sorry history as an expansion team, to make it a competitive basketball operation rather than simply another entertainment outlet fighting for tight discretionary dollars in the Kingdom of the Mouse. The NBA is counting on him to lead it into the next generation and a continuation of the spectacular personality-driven growth of the last decade that has made the league the most astonishing success story in the history of professional sports. “He’s a little mini-entertainment complex,” says his agent, Leonard Armato, “before he ever steps on the floor.” He is 7-foot-1 and 300 pounds. In March, he turned 20.

There are few doubts about his playing abilities. Of his most immediate contemporaries, he is bigger than Patrick Ewing of the Knicks, stronger than David Robinson of the San Antonio Spurs and a more instinctive defender than Hakeem Olajuwon of the Houston Rockets, for whom the game seems to have become a burden. Yet, in some ways, O’Neal is still amazingly raw. In his first exhibition game, against the Miami Heat, he committed nine turnovers, a ludicrous number for a center. There are moments when he seems to get hugely tangled in himself, and he has the devil’s own time with free throws. What he has is enormous natural ability. All he lacks is acquired wisdom.

Says the Knick guard Glenn (Doc) Rivers, who played with O’Neal in a series of pickup games this summer: “He’s going to stumble into 20 points and 10 rebounds a game just because he’s so big. He’s going to have to work on it, but he’s just so… grown-up for his age.”

In an October exhibition game in Asheville, N.C., the good and bad in him were on conspicuous display. Against the Charlotte Hornets, he put up 26 points and 11 rebounds, but he also lost the ball six times. He was duped into silly offensive fouls when smaller men moved in behind him as he powered toward the basket. Still, to watch him slap away a shot by Kendall Gill, a star of the Hornets, and then go 90 feet to drop a layup at the other end is to see almost limitless promise.

O’Neal took all of it with poise and equanimity. “I’m all right,” he said afterward. “I’m at about 70 percent, or maybe 80.”

Orlando coach Matt Guokas explains: “People tend to forget how young he is because of how big he is. He’s still learning the pro game. He doesn’t really even know the language yet.” And if he sometimes looks like an Arthur Murray student confronting the footprints on the floor for the first time (once, against the Charlotte veteran J.R. Reid, O’Neal tied himself in an enormous knot, and Reid blocked his shot), he also clearly looks like the latest coming of basketball’s most compelling mythic figure—the Big Man in the Middle.

Once, a center was called a “pivot man,” with good and clear reason. Everything about the game, from its actual strategy to its psychic rhythms, revolved around him. Over the past 20 years, however, basketball has moved up and out, away from the big men in the middle. First, Gus Johnson and Elgin Baylor took it into the air, where Connie Hawkins, Julius Erving and Michael Jordan have followed. Then, Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, neither of whom could jump conspicuously well, redefined their respective positions, largely through their mutual love for and faith in the pass. Both were 6-foot-9, but both excelled at positions previously thought to belong to smaller men. Bird played essentially the small forward’s slot, and Johnson was a point guard. Centers followed the trend as the game evolved. This led, at its best, to the multiplicity of skills demonstrated by David Robinson, and, at its worst, to the pathetic sight of Ralph Sampson, a 7-foot-4 man trying to play himself shorter.

In this, O’Neal may be the perfect synthesis of old myth and new reality. His is essentially a power game, but it is infused with the kind of speed and agility required by modern professional basketball. He will handle the ball on the perimeter if he must (the first play he ever made that caught national attention came in a televised all-star game after his senior year at Robert G. Cole Senior High School in San Antonio, when O’Neal grabbed the ball off one backboard and took it the length of the floor to dunk at the other), and he is working on a jump shot. But his greatest gifts remain in the classic pivot—close in with his back to the basket. There, he is that thing most beloved by the savants—a “quick jumper,” rising apparently from his ankles and calves without ever appearing to gather himself.

The Big Man in the Middle endures as an archetype, largely because he was so much of what first made basketball unique. Wilt Chamberlain once pointed out that “nobody loves Goliath,” as an excuse for his enduring unpopularity. He was wrong, of course, even scripturally: the Philistines loved Goliath. If O’Neal comes up a little short of Goliath’s six-cubits-and-a-span, his talents and, more importantly, his personality may make him the living refutation of the Chamberlain theorem. He has a quick smile that instantly takes five years off his age. This is what the Magic and the NBA are counting on—a Goliath everyone can love.

For to be merely a player—even a great player—is no longer all there is in the NBA. The league creates stars now, a culture of celebrity that could not have been anticipated in the late 1970s, when the NBA was in very real danger of collapsing altogether. There is an inexorable blurring of the line that separates entertainers and athletes. Most recently, Charles Barkley appeared in a cartoon brawl with Godzilla. This culture reached its apex at the Olympic Games in Barcelona, when the United States team, featuring Bird, Johnson, Jordan, Barkley and other NBA stars, careened across Europe like some strange, elongated outtakes from A Hard Day’s Night.

He drives a burgundy Blazer with the license plate “Shaq-Attaq,” and his black Mercedes sports a front plate that reads, “Shaqnificent.”

That culture of celebrity has its benefits; for example, Jordan’s carefully crafted public image largely insulated him from accusations of high stakes gambling leveled against him last season. But it’s also a fragile culture, largely black and formed during a decade of racial reaction. It needs constant renewal. Bird and Johnson are both retired, and Jordan insists that he will not play much longer. To survive, the celebrity culture that fueled the NBA’s rise needs new, young, charismatic players while it continues to finesse the problems of race and class that bedevil every other institution today.

As soon as he left college last spring, Shaquille O’Neal became the de facto leader of that next generation. No less an authority than Magic Johnson sees that. “He’s got it all,” says Johnson, who worked out with O’Neal in Los Angeles last spring. “He’s got the smile, and the talent, and the charisma. And he’s sure got the money, too.”

Indeed, Shaquille has a goofy kid’s smile that runs up the left side of his face a little faster than the right. On his first day at a summer construction job at L.S.U., he jumped off the roof of the house on which he was working, terrifying the occupants. When a couple in Geismar, La., named their infant son Shaquille O’Neal Long—simply because they loved the name—Shaquille immediately drove out and had his picture taken with the baby.

And he does have something of a sweet tooth for cars. He drives a burgundy Blazer with the license plate “Shaq-Attaq,” and his black Mercedes sports a front plate that reads, “Shaqnificent.” Both are parked at his new house in Isleworth, a luxury suburb outside Orlando. The first thing he did after signing his Orlando contract was to return home to San Antonio and treat two of his friends to a trip to an amusement park. This, from a newly minted millionaire who announced on his first trip to Orlando that he was looking forward to “chillin’ with Mickey,” and who explained on the opening day of the Magic’s training camp, “I was a child star, just like Michael Jackson and Gary Coleman.”

Dennis Tracy, who has signed on as his friend’s unofficial media liaison, says: “I can’t see him ever changing. He’ll always be that kid who jumped off the roof because it was fun to do.”

So far, O’Neal has done all the right things. He signed quickly and without rancorous negotiation. He defused a potentially messy situation over his college No. 33, surrendering it to his veteran teammate Terry Catledge. Over the summer, he impressed current NBA players with his love for hard work and, oddly enough, with his punctuality. “The most impressive thing is that he’s such a mature person,” says Doc Rivers. “When we were playing at U.C.L.A., we started at 9 o’clock in the morning, and he was there right on the dot every day. You don’t see many college kids like that.”

O’Neal listens attentively as Pastor Bush winds up his talk, and then he takes the floor. He is playing with Skiles, who is already in game shape and driving his teammates hard. Roberts, a former L.S.U. teammate of O’Neal’s, tries to shoot a jump shot over him, and O’Neal slams the ball off the floor in a 10-foot carom. Skiles is not impressed. “Shaq,” he says, “block it back to someone on your team.” Shortly thereafter, Stanley Roberts has had enough, and he walks off the floor, claiming an injured leg.

Thunder peals outside, and there is a flash that shows the wire threaded through the thick window glass above the bleachers. On the first day that Shaquille O’Neal came to Baton Rouge, the skies darkened and roared, and a small tornado blew through town. Scared to death, he rode around on Dennis Tracy’s bicycle with the storm blowing up all around him.

There is portent to the way he plays. His team wins. The lightning cracks.

“O.K.,” says Scott Skiles, looking up at his newest teammate. “You guys bring it back.”

It is a comfortable world that Shaquille O’Neal joins. Between 1981 and 1991, the NBA’s gross nonretail revenue grew from $110 million to $700 million—an increase of 636 percent. Its gross retail revenues, which include the vastly profitable licensing of team jackets and caps, exploded even more vigorously, now totaling more than $1 billion per year.

As recently as a decade ago, there was serious talk of folding at least three and possibly as many as six franchises. Now, the average franchise is worth approximately $70 million, and there is talk about selling the Boston Celtics alone for $110 million. “There is no one place that it changed,” says the NBA commissioner, David J. Stern. “A number of things that the owners and players did provided a better stage for all our players.” Indeed, on the two most volatile issues of the past 20 years in professional sports—money and drugs—the NBA and its players have developed workable solutions, while largely avoiding the acrimony that has become customary in both baseball and football.

The league’s greatest triumph has been to inculcate in everyone a fundamental loyalty to the idea of the league. Hence, Stern talks about “the NBA family.” “It may not be a traditional family,” he says, “but it is an extended family.” This has provided NBA players with a stable foundation from which to kick off their own lucrative careers. Each generation builds on the previous one. Erving’s abilities as a player and as a public person made it easier for Bird and Johnson, who made it easier for Michael Jordan, who took the whole business to another dimension. Without Erving, who proved once and for all that black athletes were neither brooders nor cartoons, Jordan’s entree into the corporate class would’ve been that much more difficult. In turn, Jordan’s success eases the burden on O’Neal.

“Ego is acting like you’re all that,” he says. “Like they say on the block, ‘all that.’ Can’t nobody touch you,” he says. “Confidence is knowing who you are.”

He joined the family at the end of last year’s college season, leaving L.S.U. with one year of eligibility left. He was tired of being triple-teamed and physically roughed up. “I played my heart out,” he says. “But there was one game, I was catching alley-oops all day. So, in the second half, I was doing my spin move, and guys were putting their butts into my leg, coming under me. It was not a money thing. I was taught at a young age that if you’re not having fun at something, then it’s time to go.”

The lesson came from his father. In the early ’70s, with Newark just beginning to turn from the riots of 1967 into something even more lost and hopeless, Philip A. Harrison decided to get out. He joined the Army and, before he could marry Lucille O’Neal, he was shipped overseas. She had their baby without him. Looking through a book of Islamic names, she called him Shaquille Rashaun O’Neal, which, she says, means “Little Warrior.” “I wanted my children to have unique names,” Lucille says. “To me, just by having a name that means something makes you special.”

The couple married soon thereafter. The family held together in the gypsy jet stream that is military life. “The best part for me was just getting out of the city,” Shaquille recalls. “In the city, where I come from, there are a lot of temptations—drugs, gangs. Like, when I used to live in the projects, guys’d ride by in their Benzes. Kids want to have the fancy clothes and the Benzes. They say: ‘Look at Mustafa. He’s done this and done that. I want to do that.’ When I was little, I was a kind of juvenile delinquent, but my father stayed on me. Being a drill sergeant, he had to discipline his troops. Then, he’d come home and discipline me.

“The worst part was, like, traveling, you know? Meeting people, getting tight with them, and then having to leave. Sometimes, you come into a new place, and they’ll test you. I always got teased. Teased about my name. Teased about my size. Teased about being flunked. You know, ‘You so big, you must’ve flunked.’ I’d have to beat them up. It took a while to gain friends because people thought I was mean. I had a bad temper. Guys used to play the ‘dozens’ game with me where they used to talk about your mother, and I’d get mad and hit them. One day, I just woke up and walked away.”

They moved to Germany twice, the last time just before Shaquille entered junior high. It was a tight, regimented existence. In Fulda, where Sergeant Harrison was stationed, there was some anti-American agitation; in one bizarre protest, the townspeople painted American military vehicles a bright blue. It is significant, then, that, for all his travels, Shaquille still calls Newark his home and that “the projects” loom so large in his personal iconography despite the fact that he spent very little of his life there. “He didn’t want to leave,” his father explains. “He wanted to stay there with his grandma.”

But that was not the way that the sergeant’s family functioned, and all four of his children knew it. “Society is always dictating to the parent who’s the boss,” says Harrison, who will retire as a staff sergeant in September 1993 and move his family one last time—to Orlando. “You know who the boss is today in the family? The children. My dad disciplined me. Your dad disciplined you. What was said about it? Now, everybody’s in the middle. Back then, the people in the middle were your friends, so you didn’t disrespect them. Now, somebody runs to the court.”

One day near Fulda, Shaquille went to a basketball clinic run by Dale Brown, the energetically eccentric basketball coach at L.S.U. Brown presumed that the big young man was a soldier. Discovering that Shaquille was, in fact, barely a teenager, Brown’s coaching antennae vibrated into the red zone, and he asked to meet the sergeant. Five years later, after Harrison was posted to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio and after Shaquille became a high school all-American at Cole, L.S.U. recruited and won him. It was presumed that Harrison made the choice for his son. “That was him alone,” Harrison says. “We pushed the boat away the day he decided to go there. We told him, ‘Go out there and take what we taught you and what you learned in life and apply it and do what you have to do.’”

In college, O’Neal became a superstar, despite breaking his leg during his sophomore season. By the end of last season, he was averaging 24.1 points per game. But the Pier 6 strategy of rival coaches was wearing his patience thin. In addition, Brown seemed unable to keep O’Neal as the focal point of the L.S.U. offense, something that drove NBA types mad when they looked at tapes of the Tigers, and something that they blame for the rough edges that still exist on his game.

“I saw one game last year when this kid touched the ball about twice in the entire second half,” says one NBA scout. “I said, ‘Is this guy kidding or what?’” O’Neal managed to restrain himself until the Southeastern Conference tournament, when he became one of the instigators of an ugly brawl in which even Brown was seen throwing haymakers at the opposition. Shaquille was suspended for the Southeastern Conference championship game the following day. After L.S.U. was eliminated early in the subsequent N.C.A.A. tournament, he made his decision to turn professional. He closed his bank account and went home to San Antonio.

His father always had insisted that O’Neal would stay the full four years at L.S.U. His parents had tried to impress upon their son the value of a college degree. In addition, Philip Harrison had emphasized the vast differences between the college game and the one that is played in the NBA. But the scene at the Tennessee game gave even the sergeant second thoughts. “I told him I wanted to leave,” Shaquille says. “It was not that hard. He just thought about it and finally, he said, ‘If I was you, I’d want to leave, too.’ Not because of the money, but because I wasn’t having any fun. Everybody thinks he’s a dictator. He’s not.”

His father laughs now. “Everybody’s got this myth that, when the sergeant speaks, everybody listens.” He points at his wife: “When she speaks, everybody listens.”

Shaquille announced his availability for the draft on April 3, and he was taken into Stern’s NBA family almost immediately. Through Dale Brown, the family had met a Los Angeles-based agent named Leonard Armato, who also represents Hakeem Olajuwon, and who also had helped straighten out the tangled public image of Kareem Abdul Jabbar. Armato agreed to represent Shaquille. In June, he went to the NBA finals in Portland, where he was interviewed by Ahmad Rashad. Endorsement offers bloomed everywhere. It was a dizzying time, and Shaquille handled an array of new situations with conspicuous aplomb.

Counselors who work with them say that military children adapt quickly, that they develop social skills faster than other children their age. Shaquille was formed within a dynamic that was at once very stable, and at the same time in predictable flux. Every three years, as the sergeant was rotated between duty stations, there were new places to see and new friends to make. Even though he seems to cling to Newark as some sort of cultural touchstone, Shaquille learned very early in his life to function in different contexts with ease and confidence. He has been an urban homeboy and an American abroad, a Texas schoolboy legend and a college star. He is going to be a professional star, a commercial spokesman and a national celebrity.

“Ego is acting like you’re all that,” he says. “Like they say on the block, ‘all that.’ Can’t nobody touch you,” he says. “Confidence is knowing who you are.”

At various times during his career, the Orlando general manager, Pat Williams, has treated NBA crowds to halftime entertainments involving singing dogs and wrestling bears. He has become known as the league’s premier showman, occasionally at the expense of his reputation as a basketball man. Williams needed to sign O’Neal quickly. For the first few seasons, the Magic were content to sell the entertainment side of the NBA experience. But, in an area where there were so many other entertainment options, it became incumbent upon the team to move toward competitive basketball, lest it drop down past Sea World on the food chain of local attractions.

O’Neal plays with consummate ease and confidence. He blocks shots by catching them. He whips down the lane for a dunk off an inbounds play, and he winks at Leonard Armato’s 4-year-old son while he does it.

“As great as Disney and Sea World are,” explains Jack Swope, the Magic’s assistant general manager, “they’re not considered something that local people can identify with. It’s hard to root for Disney World.” It’s just as hard, however, to root for a basketball team that wins 20 games a year. O’Neal would be the link between the entertainment function of the Magic and the athletic one.

Immediately after the draft, a nervous Williams couldn’t even find his new star. There was nothing coming from the O’Neal camp, he says, like “yippee, we’re glad Orlando won the lottery. There were no warm-fuzzies coming out of that end for about a month,” he says. In addition, Williams was having trouble with the NBA salary cap: It stabilized the league’s fiscal situation, but it also requires general managers to contort themselves regularly through baffling mathematical gymnastics just to get their rosters filled.

Orlando’s situation was complicated further when the Dallas Mavericks signed Stanley Roberts, a restricted free agent, to an offer sheet that totaled $15 million over five years. The Magic had to match that offer within 15 days or lose Roberts without compensation. Moreover, because of salary cap restrictions, the Magic had to sign O’Neal before matching the offer to Roberts.

Williams was going in several directions at once. To make room for O’Neal under the salary cap, he traded guard Sam Vincent to Milwaukee and restructured five other existing contracts. On Aug. 4, O’Neal signed for a reported $40 million over seven years. Orlando also matched the Dallas offer to Roberts, whom the Magic then traded to the Clippers in September in a deal that brought two first-round draft picks, which will be used to put the required supporting cast around O’Neal.

It was a remarkably civil negotiation. “To their credit, Shaquille and his people were bright enough to understand,” Williams says. “They worked with us in those 15 days. Most people thought we couldn’t do it. But we did it.”

That left Armato free to develop the rest of what he calls Shaquille’s “entertainment complex.” While the Magic own the rights to everything with their name on it, O’Neal is free to make whatever outside deals he can. (For example, he can do television commercials, but he can’t wear his uniform in them without the prior approval of either the team or the league.) Soon, a lucrative deal was signed with Spalding for the Shaquille O’Neal basketball, and one is in the works with Kenner for a line of Shaquille action figures. Since Armato made his reputation primarily as a shrewd money manager—as opposed to as a hardball negotiator like David Falk, the Washington attorney who represents Patrick Ewing—O’Neal feels confident that his long-term interests are secure.

“We’ve got good investments going,” he says. “We’ve got stocks, T-bills. We’re all right.”

Armato plans a unified marketing strategy and a logo currently being designed by a team of graphic artists in Los Angeles. “We’re thinking of a single image for Shaquille through all of the products in a way that benefits all of them,” Armato says. “Let’s say it’s a soft drink: The ‘Shaq-Pack.’ On the package as a prize, maybe there’s a Shaquille basketball, or a pair of shoes. The NBA is putting Shaquille in 100 different countries by itself.”

The most obvious modem endorsement is a shoe contract. It’s almost unfathomable today to realize that Kareem Abdul Jabbar once made only $100,000 a year to wear Adidas basketball shoes. In 1983, Nike had passed Adidas as the leader in worldwide sales. The following year, however, Reebok, a smaller, Boston-based company, took over the market from floundering Nike, largely by catching the aerobics boom that Nike missed. Later in 1984, though, after Nike signed Michael Jordan to an innovative promotional deal, Nike won back the market again—by September 1985, the company had sold more than 2.3 million pairs of Air Jordans alone—and Reebok now plans to counter Jordan with Shaquille O’Neal, whose size 20 feet will be shod in Reeboks in exchange for a reported $10 million over the next five years. Nike and Jordan made this deal possible, and Reebok and O’Neal plan to repay the favor by bringing them down out of the air.

“He is going to be the focal point of basketball for us,” says Mark D. Holtzman, Reebok’s director of sports marketing. “We want to portray him as the strongest man in the NBA, and we want to do it worldwide. We’re going to put him in 50 countries.” Reebok is hanging new technologies on the “Shaq Attaq” shoes as well, which will retail for more than $100. O’Neal spent part of September shooting the first commercials for them.

Every step he takes now has consequences. Every move he makes sets off tremors, and his first NBA season is barely a week old. When he and Catledge were wrangling over No. 33 in Florida, the NBA licensing people grew edgy in New York, since they didn’t know what number to put on their official Shaquille gear.

O’Neal is aware that the commercials he so enjoyed making will contribute to a deadly consumer culture that grips the projects where he has anchored his past, to that look he saw in the eyes of the kids who wanted the Benzes long ago. He is going into a culture of celebrity that has been accused of abandoning its most impoverished adherents.

“I’m worried about that,” he says. “I’m not going to make myself a superhero that people can’t touch. The commercials are going to show both sides of me, what I like to do off the court, like listen to my rap music.

“The question was asked of me, should athletes be role models? The answer is, yes, to a certain extent. Like, when I was a kid, I could look up to Doctor J, but if I needed some advice about the birds and the bees, I couldn’t ask Doctor J. I couldn’t call one of these superstars. I had to call Mommy or Daddy. I mean, we should carry ourselves well on TV. We should not do things like beat our girlfriends up, do drugs or alcohol. Now, if all those kids lived with me, then I could be their role model.”

The Forum Club is hopping. Once the NBA was armories in places like Davenport, Iowa, and Rochester. Today it is the Great Western—formerly Fabulous—Forum in Los Angeles. Once it was steelworkers and mill hunks. Today it is agents and movie stars and singers. In the Forum Club, there is taffeta and lace, leather and gold. There is loud talk of agents and properties and the hot places to go later that night. Ice rings like delicate chimes. It is a basketball evening in Los Angeles, and the sky outside is a perfect parfait.

Every August, Magic Johnson hosts a benefit game for the United Negro College Fund. O’Neal has come to play this year. His coach is Arsenio Hall. Coaching the other team is Spike Lee. The singer AI B Sure sits in one section with the female singing group En Vogue. At midcourt, Jack Nicholson sits with his infant daughter, whose parents will later mutually determine that they no longer want to live together in separate houses. It’s a long way from North Park Baptist Church, a great distance from Pastor Bush and his little beam from God’s eye.

He will be a Goliath for everyone to love.

O’Neal plays with consummate ease and confidence. He blocks shots by catching them. He whips down the lane for a dunk off an inbounds play, and he winks at Leonard Armato’s 4-year-old son while he does it. He tosses the veteran Pistons center Olden Polynice this way and that, once bouncing the ball off the backboard, retrieving it with a lightning first step, and then slamming it through as the women from En Vogue rock and Arsenio grabs his head. He ends up with 36 points and 19 rebounds. “Shaquille, the best part about him is that he’s mean,” Magic Johnson says later. “He’s going to be one of those guys that, after you play him, you sleep real good. He’s gonna put guys to sleep.”

He does not look mean. He does not look like a product here. He looks like a 20-year-old discovering himself all over again. There is a purity that extends from north Orlando to this gathering of gaudy dilettantes. He will be comfortable in both places. He will be a kid and a corporation. He will be for sale and he will be free. He will be a Goliath for everyone to love.