I. 80 DAYS IN THE LIFE OF BOB ARUM

From his fourteenth-floor, comer suite on Park Avenue and 57th Street, Bob Arum, the man many consider the most powerful boxing promoter in the world today, has a commanding view of midtown Manhattan. The center of gravity of the boxing business, like that of the city itself, has moved north and east over the years. Once, Madison Square Garden was the most prestigious arena in the country. By controlling its gate, promoters like Tex Rickard, Mike Jacobs and James Norris dominated the fight game for nearly half a century. Today, the Garden is no longer the main event. Real power has moved uptown. From Arum’s office, one can see the outlines of an imaginary ring—north, up Madison Avenue, to rival promoter Don King’s 69th Street townhouse; west and south to the television networks along Sixth Avenue; and east back to Arum’s office—within which most of the modern-day business of boxing is transacted.

But, for all these geographical shifts, the fight business is much the same today as it always has been: two men in a ring beating each other’s brains out and a third man at the door selling tickets. The man selling the tickets may be better dressed and better educated, the men in the ring may be better paid, and the success of a fight may be measured in Nielsen points instead of gate receipts, but boxing remains, as Arum himself describes it, “the last refuge of desperadoes.” There are no universal rules, no leagues, no regularly-scheduled seasons. The competition outside the ring can be as primitive and as brutal as it is inside. And the future is always up for grabs—at least until the present catches up with it.

When he opens his mouth, Arum sounds as if he’s getting ready for a shootout. His weapons are a telephone and a pencil.

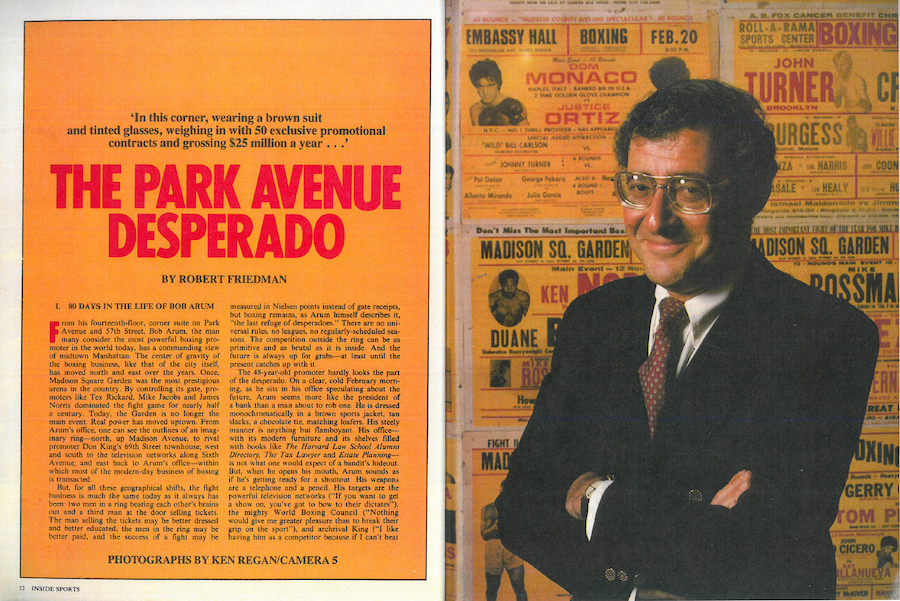

The 48-year-old promoter hardly looks the part of the desperado. On a clear, cold February morning, as he sits in his office speculating about the future, Arum seems more like the president of a bank than a man about to rob one. He is dressed monochromatically in a brown sports jacket, tan slacks, a chocolate tie, matching loafers. His steely manner is anything but flamboyant. His office—with its modem furniture and its shelves filled with books like The Harvard Law School Alumni Directory, The Tax Lawyer and Estate Planning—is not what one would expect of a bandit’s hideout. But, when he opens his mouth, Arum sounds as if he’s getting ready for a shootout. His weapons are a telephone and a pencil. His targets are the powerful television networks (“If you want to get a show on, you’ve got to bow to their dictates”), the mighty World Boxing Council (“Nothing would give me greater pleasure than to break their grip on the sport”), and archrival King (“I like having him as a competitor because if I can’t beat him his own ego eventually will”).

He is not just shooting from the hip. Arum has, in his pocket, exclusive promotional contracts with a number of champions in different weight classes. These agreements are the source of his power. By tying up the rights to a champion’s future fights, a promoter can usually force a contender looking for a title fight to give up options on his future fights should he win. The new champion thus becomes another link in the promoter’s chain. (In 1959, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that similar practices, as engaged in by the International Boxing Club, violated federal antitrust laws. The IBC, which was forced out of business, was accused of having three champions under exclusive contract at the same time. Clearly, the game has changed. At one point last year, Arum had eight.)

This morning the future, as seen through the promoter’s tinted glasses, looks especially rosy. Within the next two months, he will be staging six title fights—three of them on a prime-time boxing extravaganza the night of March 31. In the light-heavyweight division, Arum not only controls both the WBC and World Boxing Association champions—Matthew Saad Muhammad and Marvin Johnson, respectively—but one of his most popular fighters, former champion Mike Rossman, will be making a comeback attempt later in the month. In the middleweight division, Arum has multi-fight contracts with Vito Antuofermo, the undisputed champion, as well as top contenders Alan Minter and Marvin Hagler. And, in the welterweight division, both champions—Pipino Cuevas and Sugar Ray Leonard—are now fighting for him. Although Leonard is under contract to no one but himself (“He’s sui generis,” as Arum puts it), he has hired Arum to promote his next two title defenses, including a possible bout with Roberto Duran.

But it is about the future of the heavyweight division, traditionally the most lucrative for promoters, that Arum seems most concerned—and most optimistic. The man he considers the best heavyweight in the world, WBA champion John Tate, just happens to be under contract to him. And already, Arum is thinking past Tate’s upcoming bout with Mike Weaver to a title unification match in September with WBC champion Larry Holmes—a match Arum has recently agreed to co-promote with King.

“Tate-Holmes is not a competitive fight anymore,” he says, taking a cigar from a box stamped “Bob & Sybil Arum.” (Sybil, Arum’s second wife and a former model from Hawaii, is more of a presence in the office than a name on a cigar box: She answers phones, types letters, and functions as both a confidante and an ornament.)

“Once Tate beats Holmes,” the promoter says, “we’ll invest $250,000 in pushing him. We’ll take him on a tour of the country, of the world. Get everybody to meet him. That would maximize his value for the future, because he’s going to be champion for many, many years.”

And if Tate loses?

“Not to have the heavyweight champion?” Arum muses, thinking the unthinkable. “The stakes are very, very large. If Tate doesn’t win, then we have to go back to the drawing board. But I don’t do things haphazardly. Sure, anything can happen in boxing, but we’ve planned all of this.”

He leans forward, halfway across the desk, and flicks on his calculator. “Look,” he says with a sudden intensity, “what I’m hoping is to be in a good position along about 1984 or ’85 when the business is going to switch over completely to pay television and heavyweight champions will be fighting for $20 million a fight.”

He punches some numbers into the machine and jabs his pen at an empty sheet of paper. The thought of besting the networks excites him. “I can see it now. John Tate against Marvis Frazier for the heavyweight championship of the world. I have 10 million homes on the Comsat system. I don’t know exactly what the deal’s going to be, but let’s assume Comsat takes 20 per cent of the gross revenue for use of the channel. Now the question is: What do I charge?”

Here, he pauses for a moment to do some quick mental calculations. “I think, given the rate of inflation, that I’ll be able to charge—easily and comfortably—$20 per home. Let’s say we get 30 per cent—that’s a conservative figure—of the sets in use. At $20 a pop, that’s $60 million. Comsat takes its 20 per cent, leaving me $48 million.”

He leans back in his chair again, a smile playing across his mouth for the first time all morning. “With these numbers, I can afford to pay the champion $30 million. Marvis Frazier can get more than his father ever got—say $5 million. And that would leave, after costs, $10-12 million for the company. That’s what’s going to make this all worthwhile. All this stuff now is just biding time.”

A few days later, the promoter sits hunched over in a tiny telephone stall at New York’s La Guardia Airport. The stall looks like it was designed for a midget, and Arum, though hardly a giant of a man, looks distinctly uncomfortable. In a few minutes, he will be boarding a plane for Portland, Maine, where he is staging his first fight of the 1980 season—a non-title bout between Hagler and Algerian middleweight Loucif Hamani. Right now, Arum has more important things on his mind.

“Tate will kill you,” he shouts into the phone in a voice raspy from too many cigarettes. “He’s young and strong, and you’re in no condition to fight him.”

He holds the receiver an inch from his ear as the man on the other end of the line shouts back. Something about still being the greatest.

“You’re crazy,” Arum says. “What do you need this for? Do me a favor and think it over on the plane. I’m sure you’ll change your mind.”

“Arum,” the voice responds, “you can’t say no.”

Muhammad Ali, the man on the other end of the phone, is, at this moment, sitting in an airport in Los Angeles. He is probably smiling, for he knows Arum as well as any man he has ever sparred with. He has been doing business with him for the past 14 years. And he knows that no matter how strenuously Arum may try to talk him out of making another comeback, he can’t and won’t say no. There is simply too much money at stake.

“Do I have any choice?” Arum asks a few minutes later as he fastens his seat belt. He has a silly, how-did-I-get-myself-into-this-mess grin on his face, but already his mind is racing ahead, computing just how much money he could get for an Ali-Tate fight.

Seven million dollars?

He sticks his thumb straight up and jabs the air above his head a few times. “But it’ll never happen,” he says, bringing his hand down swiftly. “Ali will change his mind when he realizes how badly he could be hurt. I got to play this out because I value my relationship with him.”

Later he would say: “What have I got to lose? Even if it ends up costing me 10, 15 thousand dollars, could I buy that kind of publicity for Tate? Nobody can say anymore, ‘Who’s John Tate?’ ”

Up in the sky this afternoon, there isn’t a cloud in sight. But, on the ground below, the vicissitudes of the boxing world will soon bring the promoter back to earth.

The first sign of trouble is a phone call the next morning from New York. Mike Rossman, the former WBA light-heavyweight champion whom Arum is grooming for another shot at the title, has decided to cancel out of a bout with Ramon Ronquillo in Atlantic City the following weekend. Rossman’s father has just filed a lawsuit against his son, and the kid is too upset to get into the ring.

Earlier in the week, at a press luncheon in Atlantic City, Rossman appears out of sorts. He keeps talking about “trying to save the ship.” Midway through lunch, his father, Jimmy De Piano (Rossman fights under his mother’s maiden name), comes over to Arum’s table. De Piano—Jimmy D as he is known to his friends—weighs a good 280 pounds without his jewelry, and doesn’t look like the type of fellow one would want to disagree with. Until recently, he was also his son’s manager. Last winter, after years of filial impiety, Rossman found himself a new manager, and together they bought out the father’s interest for $40,000. The only problem is they still owe $22,000, and, as far as Rossman is concerned, he isn’t paying another dime for what, after all, is a piece of himself. So Jimmy D has come to talk to the man with the money.

“Just send me the check,” he says in a whisper loud enough to be heard around the table. Arum tries to calm him down, but it is clearly he who needs the Valium.

“What’s happened to the feed?” he cries. “Where’s the goddamned feed?” The screen remains dark. Arum crumples into an empty $100 seat, head in his hands.

“I don’t want to make a public stink about this,” Jimmy D continues. “I just want my money before the fight. Or else somebody gets hurt. Understand?”

Considering the nature of the request, the news that Jimmy D has taken his dispute to a judge is received in Portland with some relief. One Mike Rossman fight more or less isn’t going to make a big difference in the promoter’s scheme of things.

But Jimmy D is a bad omen. All of that week, things continue to go wrong. Late Thursday afternoon, while sitting in the lounge at the Ramada Inn, Arum receives a telegram from Duran’s manager in Panama declining his offer of $1 million to fight Leonard. Arum has been hoping to deal with Duran without having to go through King, but the fighter’s loyalty to the rival promoter is proving as firm as his legendary fists. Ever the optimist, Arum announces to those in the lounge that the bad news is really “a go-ahead signal” for continued negotiations.

By Saturday, Arum is thoroughly exasperated. A predicted “record-breaking” crowd of 6,000 at the Portland Civic Center turns out to be only 4,000. “Promoter’s luck,” Arum says, blaming the low attendance on a sudden snowstorm that afternoon. A 143-pound preliminary fighter turns out to be nine pounds over weight. Arum lets the match go on. And Hamani, whom Arum has been touting as “maybe one of the two best middleweights in the world,” but who, in fact, hasn’t been in a fight in 18 months, turns out to be a stiff; he is dispatched from the ring head first in the second round. “That’s boxing,” Arum shrugs after the fight.

The high point of the weekend comes at a post-fight, pretzel-and-potato-chip affair. Arum announces he is going to promote a fight between Hamani and Mustafa Hamsho, a Syrian, for the “Arab middleweight crown.” Maybe it is just a Jewish promoter’s idea of a joke, but the fight never happens.

It is after 11 the night of March 31. The Stokely Athletic Center on the University of Tennessee campus in Knoxville is dark now. Most of the 12,769 fight fans have gone home. Above the empty ring where Tate was knocked unconscious less than an hour ago, four large, white screens have been lowered like shrouds. On each of the screens, the other heavyweight champion, Holmes, is mauling a helpless opponent. His punches are being thrown in Las Vegas, 1,740 miles away, but their impact can be felt here in Tennessee. No matter where you stand in the arena there is no escaping the electronic image of Holmes dancing on Tate’s canvas grave.

In the dark, Arum is pacing the perimeter of the ring. His head is thrust slightly forward as he walks. His lips are tightly drawn. His eyes are fixed on the littered, concrete floor. He is alone.

As he pauses to light a cigarette, the picture suddenly goes dead. The voice of Howard Cosell from Las Vegas is silenced. Arum throws his arms in the air, as if beseeching some authority even higher than Roone Arledge. “What’s happened to the feed?” he cries. “Where’s the goddamned feed?” The screen remains dark. Arum crumples into an empty $100 seat, head in his hands.

For Arum, the evening has been a disaster. (Later, at a somber, post-fight party, he will refer to it as the “Passover Night Massacre.”) Two fighters with whom he has exclusive promotional contracts—Tate and light-heavyweight Marvin Johnson—have lost their WBA titles in the same ring on the same night. Although Arum expects to make nearly $500,000, he has suffered a stunning setback in his bid for undisputed control of the sport.

For two hours, he sat at ringside glumly watching the seconds slip away on a pocket-sized, digital stopwatch. He tried to put the best face on what was happening inside the ropes—telling reporters seated near him how impressive his fighters looked whenever they scored a punch; smiling lecherously when the blonde University of Tennessee cheerleaders he had hired as card girls strutted around the ring. But with each round, his composure deteriorated. By the end of the first fight, in which Johnson was bloodied into submission by top-ranked contender Eddie Gregory, Arum was on his feet, shouting orders to his subordinates over a walkie-talkie and frantically gesticulating to referees and ABC technicians to clear the ring and get on with the next bout. He had good reason to want to put Gregory out of his mind: The new light-heavyweight champion had taken a $50,000 cut in pay so he would not have to give Arum any options on his future fights.

But the next match only made things worse. Before an estimated 55 million TV viewers, “Big” John Tate, around whom so many of the promoter’s future plans revolved, was humiliated by a 15th-round knockout punch from Mike Weaver. The dramatic finish made the defeat all the more agonizing. Only 45 seconds remained in a fight Tate was winning on points. Just the week before, Arum signed a deal for a June bout with Ali that would have earned Tate an estimated $3 million. And, in September, there would have been a chance to snatch the WBC crown from Holmes and rival promoter Don King.

Now, in the darkened arena, as Arum waits for Holmes to return to the empty screen and finish his opponent, he assesses the damage. Although he has secured options on Weaver’s next three title defenses, he is stuck with a champion whose value is debased by nine previous losses, including defeats by both Holmes and Leroy Jones—the same Leroy Jones Holmes was dancing circles around when someone in the Knoxville arena mercifully pulled the plug.

II. FROM ALI TO EVEL AND BACK

If, as Evel Knievel once put it, a promoter is “just a guy with two pieces of bread looking for a piece of cheese,” then Bob Arum waited a long time before making his first sandwich. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1962, while working as a tax attorney for the Justice Department, that Arum got his first taste of boxing, and not until 1966 that he promoted his first fight. For the son of an Orthodox Jewish accountant who grew up in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn and graduated from Harvard Law School, becoming a boxing promoter was about as likely as being served a ham-and-cheese sandwich in a kosher delicatessen. But once he put on his first fight, becoming the top promoter in the business was no surprise at all.

Arum (the name is pronounced “Air-em”) was always near the top of his class. At New York University in the early 1950s, he had an A average and was president of the student council. At Harvard, he was cum laude. (Kennedy speechwriter Richard Goodwin, a classmate and still a close friend, says Arum’s grades at Harvard were legendary.) At his first job, with a prominent Wall Street firm, Arum earned high marks as an aggressive tax lawyer—high enough to land him an appointment in 1961 as chief of the tax section of the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Manhattan. Working under Robert Morgenthau, the 30-year-old assistant U.S. attorney went after such giants as Stavros Niarchos, Macy’s and First National City Bank. He won almost every round in court.

But it was a case against lawyer-turned-promoter Roy Cohn that gave Arum his most gratifying victory—and that set him thinking about a new career. In 1962, Cohn was promoting a heavyweight championship fight in Chicago between Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston. Rumors reached the Internal Revenue Service that a scheme had been devised to spirit proceeds of the fight to Switzerland to avoid paying taxes. The IRS called in the Justice Department, and Robert Kennedy, then Attorney General, called in Arum. In what Arum calls “a great operation,” revenue agents were dispatched to Comiskey Park and to some 260 theaters around the country with closed-circuit television. The money from ticket sales—nearly $5 million—never left the box office.

Arum had a realization: A promoter, if he knew what he was doing, could make a fortune in the boxing business.

In December 1965, Arum went to his first fight, an Ernie Terrell-George Chuvalo match in Toronto. That night he decided to make his move. He approached football star Jim Brown, who was doing the commentary and who was a friend of Ali: “Why can’t we do what Cohn did?” he is said to have asked Brown. “Only better.”

When Brown introduced Arum to Ali, he had no way of knowing he was acting as matchmaker for what was to become one of boxing’s oddest, and most enduring, relationships. But, within a matter of weeks, the Jewish tax lawyer and the Muslim prize fighter were contractually married. They made a perfect pair: Ali, who had been looking for a new promoter to replace the Louisville syndicate that launched his career, liked the idea of being represented by a man he called his “Jew lawyer”; and Arum, who had been growing bored with his button-down, suburban existence, liked the excitement of doing business with the Black Muslims. Their union soon led to the birth of a new company, Main Bout. Three months later, in March 1966, Arum staged his first fight.

For the next 14 years, Arum’s success as a boxing promoter would be hitched to Ali’s roller-coaster career. For many years, Arum, as Ali’s lawyer, got a fee in addition to a share of the promotion company’s profits. So dependent was he on Ali that, as Arum himself concedes, “From 1966 until 1974, I don’t think I promoted six fights that didn’t involve Ali. And that includes the three and a half years he wasn’t fighting. It would be more accurate to say I was in the Ali business than the boxing business.”

The first time Ali was derailed from the championship track—when he refused induction into the Army in April 1967—Arum partially recovered his footing by forming a second company, Sports Action Inc., to stage a heavyweight elimination tournament. But it wasn’t until Ali reentered the ring in 1970 that Arum’s fortunes began to rise again. Although he was closed out of the former champion’s triumphant return against Jerry Quarry in October, by the end of the year Arum was back in the Ali business. Yet another company was formed—this one, Top Rank, Inc., destined to survive to the present day.

Over the next three years, Top Rank promoted many of Ali’s fights as he unsuccessfully attempted to regain his heavyweight crown. Even when other promoters muscled in, Arum still collected his fee as Ali’s legal adviser. In 1972, confident that his relationship with the fighter was secure, the promoter left Louis Nizer, for whom he worked eight years, and started his own law firm.

Two years later, however, just as suddenly as Ali had come into Arum’s life, he was gone. After the second Ali-Frazier fight in January 1974, another promoter—a smooth-talking ex-convict from Cleveland by the name of Don King—offered Ali $5 million and a chance to win back his title. All Ali had to do was agree that, in the future, he would do business with King instead of Arum. The proposition was too good to turn down. And so, that October, like a fickle lover, the former champion flew halfway around the world to Zaire to reclaim his crown from George Foreman and pick up his biggest paycheck to that date.

Arum reacted like a jilted wife. His first impulse was to jump into bed with someone even bigger—in the promotional sense—than the heavyweight champion of the world. Unfortunately, he landed short of his mark. Evel Knievel, the motorcycle stuntman, may have been as great a self-promoter as Ali, but the product he was selling was made of decidedly inferior stuff.

“Ali was going off to fight Foreman for King,” Arum says, explaining how he got involved in promoting Knievel’s ill-fated, but appropriately named, Snake River Canyon Jump in September 1974. “I guess, subconsciously, I was looking for some way to keep Top Rank in the public eye. Now this guy was a super salesman. He convinced me how great this jump was going to be. And it seemed to me that a good buck could be made.”

Even today, when Arum recounts what happened on the banks of Idaho’s Snake River that Labor Day weekend, he is not quite sure whether to be embarrassed or pleased with himself. Although he admits it was “a terrible fiasco,” he can’t seem to control his tongue: “The logistics on this thing were unbelievable. We rented Lear jets, we put a fortune into the site, and the telecast itself cost us $300,000. Suddenly, from a nothing event, it was the talk of the world. The world went crazy. We were trying to figure out how much money we were going to make. It was going to be the greatest event of our time.”

Not quite. The $6 million Arum told the press he had guaranteed Knievel—$1 million more than Ali was getting from King, as Arum frequently pointed out—turned out to be $250,000. The 200,000 spectators Arum had been predicting all summer turned out to be 15,000. And the Greatest Event of Our Time turned out to be a dud.

“The guy was just drinking and screwing,” Arum says, as if abstinence might have made a difference. “That’s all he wanted to do. He hadn’t practiced anything. Well, blast-off time comes and the rocket goes off with a tremendous thunder. Knievel’s scared to death and, before the goddamned thing is off the ramp, the parachute’s out.”

Knievel ended up in the river, but it was Arum who got soaked. Did he really believe Knievel was going to risk his life for $250,000 and a percentage of the gross? “Let me tell you,” he says, still a victim of his own hype, “it was a dangerous stunt. God knows what might have happened. The problem was we oversold it. It was a show that basically appealed to children, and parents didn’t want their kids watching somebody die.”

From the bottom of the Snake River Canyon, Arum had no place to go but up. The story of his climb back reads like the concluding chapter of one of those conventional Hollywood romances: Promoter meets fighter, promoter loses fighter, promoter gets fighter back.

In late 1975, a year after Ali walked out, a man named Ronald “Butch” Lewis showed up at Arum’s office. Lewis remembers the scene: “All Arum had was a desk, a telephone and a secretary. Basically, he was out of the boxing business.” Lewis was 27 at the time, a black, silver-tongued, would-be promoter given to wearing fancy white suits and carrying a walking stick. His only dream in life was to promote a heavyweight championship fight. So Lewis decided to get some experience: He went to see Bob Arum.

At first, Arum wasn’t interested. But he soon saw in the younger man a perfect instrument of revenge. “Arum was extremely bitter,” Lewis recalls. “He told me he wanted to get back at King and at Herbert Muhammad. Now one thing about Arum—he’s a devious guy. He’ll go way out of his way to get you. And he’ll wait a year to do it if he has to.”

All through 1975, as King staged one Ali fight after another, Arum had been plotting his comeback. For months, he tried to put together an Ali-Frazier fight in Manila. He had a group of Filipino businessmen ready to put up the money, but he couldn’t get a commitment from Ali. King, who had Ali, was having trouble raising money. Over lunch at the Friars Club in New York, the two came to terms: King would promote the fight, but Arum was to be cut in for a guaranteed $300,000 and a percentage of the gross. (“The two men genuinely hated each other,” says public relations man Harold Conrad, who acted as peacemaker, “but if you dangled enough green, they’d kiss and make up.”) The “Thriller in Manila” was hardly over before the truce fell apart. Arum charged that King had shortchanged him by under-reporting the gross receipts. “He handles his business the way they do in the numbers game,” Arum told a reporter. “A master of trickeration,” King retorted. “He’s the kind of guy who tells a lie and then makes the lie come true.”

The third and final Ali-Frazier blowout, generally acknowledged to have drained the two fighters, also took its toll on Arum. Once again, he had failed to win back boxing’s biggest drawing card. “King’s relationship with Ali wasn’t all that tight,” Arum says, “but I had lost my heart. It became a bidding match between me and King, and I just didn’t want to spend the rest of my life chasing after Ali.”

Which is where Lewis figured in. The indefatigable upstart was eager to do Arum’s running for him. He flew to Miami, to Houston, to Chicago, and then to London, where Ali finally promised Lewis that, if he could come up with money, he could promote his next fight. Ecstatic, Lewis went to a group of German businessmen he had met in Zaire, found a willing opponent in Richard Dunn, and, early in 1976, 11 months after he had begun his quest, walked into Arum’s office with all the elements of a package in place. “He was like in heaven,” Lewis recalls. (Even Arum, who later had a bitter falling out with Lewis, grudgingly admits there is “a semblance of truth to Lewis’ claim that he got Ali back for Top Rank.”)

Once again, Ali was in Arum’s corner. And this time, with the exception of one brief fling with the owners of Madison Square Garden, he was there to stay.

A month after the Dunn fight, Arum staged a farcical, but lucrative, match with Japanese wrestler Antonio Inoki (“The worst thing I ever did,” he admits). In September of that year, he promoted the Ali-Ken Norton fight at Yankee Stadium which earned the champion $6.5 million, his biggest payday ever. And, in October, he signed Leon Spinks to an exclusive, three-year contract.

The following year, when King was tripped up in a television boxing scandal, Arum reasserted himself as the premier promoter in the country. He solidified his control over the lower divisions—he put on 13 non-heavyweight world title bouts that year—and he muscled in on an Ali-Shavers fight that Madison Square Garden thought it owned. (The dispute ended up in court, where a federal judge accused Top Rank of “hovering like a bird of prey.” The case eventually was settled out of court in Arum’s favor.)

By 1978, Arum had reached top form. His company had its best year, promoting 20 title fights—including the two highly successful Ali-Spinks matches—and grossing approximately $25 million. (Arum refuses to disclose what Top Rank’s profits were that year or any other.)

With Ali’s retirement, Top Rank’s revenues inevitably declined, but Arum’s dominant position remained secure. During 1979, he had as many as eight champions under contract at the same time, leading Madison Square Garden’s vice-president of boxing, John Condon, to describe him as “an octopus in the sport of boxing.”

But, increasingly, Arum found himself in the center of the ring with his gloves down. In 1978, for example, one controversy followed another like a series of stiff jabs. First, Arum was roundly thrashed for breaking an agreement to give Norton a fight with Spinks after Spinks beat Ali. The promoter decided instead to stage a rematch with Ali—a move that cost Spinks his WBC title. “Arum is ruining boxing,” Norton said, “and he’s ruining Leon Spinks along with it.” Don King accused the promoter of treating the new heavyweight champion like a “slavemaster.” And New York Times sports columnist Dave Anderson wrote that “Spinks has turned into a pawn for Bob Arum, the devious Top Rank promoter.” Arum, for his part, bluntly told a reporter: “No way is Spinks going to give up a purse with Ali. The bottom line was you had to screw Norton.”

Then, the promoter made the blunder of booking the Ali-Spinks rematch into an arena in Bophuthatswana, a South African puppet state whose government is recognized by only one other country—South Africa. That brought protests from numerous civil rights organizations and eventually led to a change of site. “It was a terrible mistake,” Arum apologized at the time. “I thought it would be a great idea holding the fight in the newest country in the world. I was totally unaware.” (A year later, fully aware of just how “independent” Bophuthatswana was, Arum went ahead and promoted a fight there anyway between Tate and South African heavyweight Kallie Knoetze.)

After the Ali-Spinks rematch in September at the New Orleans Superdome, Arum had still more trouble on his hands. A remark he made to some reporters at a post-fight party to the effect that Spinks had been drunk every night for two weeks before the bout resulted in a suit. (The case was later dropped when Arum publicly apologized to the fighter.) And a falling out with Butch Lewis whom Arum had made vice-president of Top Rank, led to a much-publicized squabble over allegedly missing gate receipts. “He was trying to destroy my credibility,” claims Lewis, now an independent promoter, “so I wouldn’t be a threat to him after I left. That son of a bitch is a shrewd bastard. As soon as he has no more use for you, he’ll stick a knife in your back.”

III. ON BEING BOB ARUM

Being Bob Arum is not an easy job. The pay is good, the travel opportunities are unlimited, and the excitement is never-ending. But what one earns in material rewards, one loses in emotional taxes. For every dollar made, more and more is withheld in affection. And, for a man in as high a tax bracket as Arum, life can be miserable. Indeed, few men in the sport of boxing are more intensely disliked.

It is not that Arum is more dishonest or corrupt or ruthless than anyone else in the business. He is not. When pressed, his detractors are usually unable or unwilling to come up with specifics. (Most of them understand that in the small world of boxing they will probably have to do business with him one day.) The charge most frequently made is that he exerts undue influence over the ratings and affairs of the WBA. But, despite the appearance of control, little hard evidence of impropriety has emerged.

Rather, there is something about the promoter’s very being—some inimical force—that seems to make people uncomfortable. To be sure, there are those who have nice things to say about Arum—that he has a brilliant legal mind; that he works hard; that he earns more money for his fighters than did promoters in the past. But no one goes so far as to say they actually like him. “He’s all right to talk to,” says Bert Sugar, editor of Ring magazine. “Just don’t turn your back on him.”

To observe Arum over a period of several weeks is to understand why people are both drawn to his power and repelled by his presence. He is monomaniacal, uninterested in all things unrelated to boxing. He is the man with the deal, the man with the authority to dictate the terms of the future. For him, the ordinary virtues of truth, loyalty and compassion have little meaning. Self-interest is his only guide. What happened yesterday is to be forgotten, what is happening today is to be exploited, and what will happen tomorrow is to be sold off to the highest bidder. Former New York Times sports columnist Robert Lipsyte, who saw a lot of the promoter during Ali’s glory years, perhaps puts it best: “The remarkable thing about Bob Arum is his ability to passionately believe in whatever is to his best interests of the moment. I never had the feeling that he was consciously lying—even when he was telling me the most outrageous things.”

That ability to exaggerate with conviction, to lie without knowing it, is what has made Arum such a successful promoter. It is the secret of all great salesmen. King, who is not above self-interest himself, used to tell a parable that illustrated the same point, though somewhat more obliquely: “Arum reminds me of the asp who asks the alligator to ride him to safety because the flood waters were rising. ‘You know you gonna bite me,’ the alligator says. But the asp tells him that wouldn’t make no sense because ‘If you die, I die, too.’ ‘That do make sense,’ the alligator says. They get to the middle of the creek and, sure enough, whomp, the asp bites him. ‘Why? Why? Why?’ says the alligator. ‘Now we both drowning.’ ‘I can’t help it,’ says the asp. ‘I’m a snake.’ ”

“I never really disliked Arum,” King says after the press conference, “I just disliked his ways.”

Whether a snake, or just a shrewd businessman, as he prefers to see himself, Arum has managed to thrive in a world where a man’s word is good only until the next one is uttered, where all fighters are great until they lose, and where ethics are of no value at all. “In Arum’s book,” says Butch Lewis, “it’s who gets who first. The man has no feelings, no morals. The dollar sign is his only God.”

Unfortunately for Lewis, who prays to the same deity, most people in the fight business, as much as they might dislike Arum, still recognize him as the high priest, the man who not only promises salvation but who delivers. Take Marvin Hagler. For years, he had trouble getting a fight. He was too good. Then Hagler found Arum. The promoter promised the fighter a shot at the middleweight title if—and only if—Hagler would give Arum the rights to his next three fights. Hagler accepted the terms and, sure enough, he got his chance last November against Vito Antuofermo.

“Arum’s a man of his word,” Hagler said before his fight with Loucif Hamani. “It’s a pleasure doing business with him. He promised me a shot at the middleweight championship, and he stood on his word.”

Privately, however, Hagler was known to want a shot at Arum. After his controversial draw with Antuofermo, he had asked Arum for an immediate rematch. But the promotor—who now owned the rights to Hagler’s next three fights for the fixed-in-advance sum of $300,000, as well as the rights to Antuofermo’s fights—had other plans. He would wait until September to stage the rematch, by which time he expected to generate more excitement—and more television money. (Antuofermo’s loss to Alan Minter in March upset these plans and further frustrated Hagler’s quest for the title, since Minter would likely stay out of Hagler’s reach as long as possible. In fact, a Minter-Antuofermo rematch is tentatively scheduled for London on June 28, Arum promoting.)

“Arum’s the manipulator, the kingpin,” says Steve Wainwright, Hagler’s angry attorney. “He’s interested in what will make the most money for Bob Arum. Hagler, on the other hand, is only interested in the belt. We’ve done business with Arum in the past because he’s been able to deliver. But we do not want to sell our souls to him.”

IV. CLOSING REMARKS—FOR NOW

“My biggest problem right now is that I’ve got to figure out a way to keep Don King in business. I like having him around. I mean, as a competitor, I want to beat him. But, as a businessman and a promoter, I need him around.” —Bob Arum, March 29, 1980

That statement, made over dinner two days before the Tate-Weaver fight, would soon come back to haunt Arum. After the setbacks of the preceding weeks—the foul-ups in Portland, the cancellation of the Rossman fight, the loss of Antuofermo’s title—the promoter was feeling confident again. The day before, he had signed a $10 million deal for a Tate-Ali fight in the Superdome in New Orleans in June. That very morning, he had obtained what he thought (or claimed) were the exclusive promotional rights to Duran-Leonard—a deal that would have left King out in the cold on one of the richest promotions of the year. He could afford to shed a few crocodile (or were they alligator?) tears for his old enemy.

And yet there was some truth to his words. Don King had been good for Bob Arum. Like Coke and Pepsi, Ford and General Motors, Democrats and Republicans, each had boosted the other’s business. On the surface, they were opposites: one white, the other black; one a graduate of Harvard, the other of Marion. Correctional Institution; one tight-lipped, the other’s mouth never at rest. But they had more in common than they let on. Neither would have got where he was without Ali and neither was willing to give up what he had without a fight.

Although they called each other names in public, in effect, the two men functioned as an informal boxing cartel. Between 1976 and 1978, for example, they had what Arum calls “a pretty concrete dividing line” when it came to selling television rights: Arum took his fights to CBS, King took his to ABC, and, practically speaking, nobody else had access to the airwaves. This arrangement broke down in 1978, when Roone Arledge convinced Arum to bring the second Ali-Spinks fight to ABC. The two men also profited from the divided titles in most weight classes. King, who was close to the WBC, was thus able to have his set of champions, and Arum, who was on good terms with the WBA, had his. It didn’t always work out that neatly, but there were plenty of title fights to go around.

All of this, as both men wanted it, left other promoters with little opportunity to get ahead. So-called “third promoters” could discover fighters and build them up, but when they went looking for a title fight, they had to come to either Arum or King. (Murad Muhammad, an independent promoter (he has contracts with Ali and light-heavyweight James Scott), had a difficult time getting his foot in the door. “Arum and King fight in public,” he complains, “but when someone else comes on the scene they join hands to keep them out.”

In the past two years, although King had Holmes, the best of the heavyweights, Arum had clearly gained the upper hand in the battle of the promoters. Two days before the Tate-Weaver fight, he could be excused for pulling his punches. King was wobbling, and behind him no other promoter was in sight. But, on March 31, the solution to Arum’s “problem” would be staring him in the face. With one punch, Weaver would put King back on his feet and turn the fight promotion business on its head.

“I welcome all the help Bob Arum can give me,” he says, when told about the other promoter’s “problem,” “’cause it sure has been difficult to survive.” Then, between peals of laughter that freshly jolt his hair and ripple the frills of his shirt, he asks, “Did he really say that?”

It is April 23, and King is, at this moment, standing in one corner of a ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria waiting for a press conference to begin. At the other end of the room, Arum is shouting into a microphone, trying to clear all the photographers and cameramen from the stage. Even this simple task seems beyond his diminished powers: No one is paying attention. King and Arum in the same room is news, but the more than 200 reporters there are more interested in two other men who happen to be in the ballroom—Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran.

In the three weeks since the Passover Night Massacre, Arum has suffered a series of reversals. First, he had signed and then lost a fight between Ali and Weaver. Although he buoyantly claims this morning that he will eventually get the fight back and that “the fun is just beginning,” it is looking more and more likely that if Ali fights anyone, it will be Holmes sometime this summer. (The deal for an Ali-Weaver fight was signed in Arum’s hotel room in Knoxville just hours after Tate’s knockout. Arum had the rights to Weaver’s next fight, but he had assumed that Ali would want to fight Holmes. So he was surprised when Murad Muhammad, who had secured the rights to Ali’s next fight, offered him $2 million for a bout with Weaver. Arum was even more surprised two weeks later when Murad suddenly changed his mind and called King in Panama to offer Holmes the fight. According to Murad, the Weaver fight fell through when Arum demanded control over the television rights. “He was trying to push me against the wall,” Murad says. “He was taking a gamble that I had no place else to go. He was playing Russian roulette, and he ended up shooting himself.”)

“I can’t afford to be knocking the same guy I’m in bed with. If I wasn’t in bed with him, maybe I could.”

Equally distressing was what had happened with Leonard. Unable to pry Duran loose from King, Arum decided to match Leonard, the WBC champion, with Pipino Cuevas, the WBA champion. Fearing that Duran was being closed out of a fight, King stepped in. First, he exerted pressure through the WBC, which insisted that Leonard fight Duran, the number one contender, or be stripped of his title. Then, he got the government of Panama (Duran is Panamanian) to intercede with the head of the WBA (who is also Panamanian) on behalf of his countryman. The WBA subsequently announced that it was withdrawing its sanction of a Leonard-Cuevas match on the grounds that Cuevas had to fight Duran, also the number one contender in the WBA, before he fought Leonard. The net effect of all these complicated maneuvers was to bring Leonard and Duran together—and with them, Arum and King.

So, here are Arum and King at the Waldorf, working together for the first time since Manila almost five years ago. And the sight of them with their arms around each other—of Arum introducing King as “my good friend”—is like watching history being rewritten. But the seeds of future discontent are sown even before the press conference is over. When a reporter asks if Madison Square Garden is a possible site, King quickly says, “Yes,” and Arum just as quickly says, “No.” (Arum has been at war with the Garden’s management for years.) When another reporter asks if the two promoters have a side bet on the fight, Arum whispers to King not to answer.

Arum is obviously uncomfortable having to share the stage with King. Being King’s equal again, after so many years of ascendancy, does not sit well. And King seems equally uncomfortable with the partnership, perhaps sensing that it is only temporary, that Arum is always capable of maneuvering himself back to the top. After all, he still has half the Leonard-Duran promotion, continued close ties to Ali, and a string of options in other weight divisions that could keep King boxed out for years.

“However, at this particular time, we’ve got a moratorium. I can’t afford to be knocking the same guy I’m in bed with. If I wasn’t in bed with him, maybe I could. But, under the circumstances, I am in bed with him. Right now, Arum and I are partners, and I don’t want to do anything that would be detrimental to the promotion of the fight. It would be stupid, just outright stupid, for me to say anything negative about Arum at this particular time.”

He pauses, and then, almost as an afterthought, adds, “See me in a month.”

[Photo on original magazine spread by Ken Regan/Camera 5]