March 1983—In the motel’s living room two women in their late thirties, wearing much too much makeup, and clothes too tight covering too much flesh, hovered over a hot plate, concerned that everything would taste right “for him.” In the bedroom, behind closed doors, dressed in a robe and stocking cap, his face covered with a facial mask, Marvin Gaye accompanied by three biceped roadies (bodyguards?) watched a fight on Wide World of Sports. Marvin and I sat next to each other in tacky motel chairs, his attention wandering from our conversation to the fight.

I anticipated an upbeat conversation full of the self-righteous I-told-you-so fervor so many performers, back from commercial death, inflict upon interviewers and the public. After all, Gaye was in the midst of one of the most thrilling comebacks in pop music history. “Sexual Healing,” some freedom from the IRS, CBS’s mammoth music machine in high gear for him, and adoration from two generations of fans, were all part of a wave of prosperity. Even his stage act, in the past marked by a palpable diffidence, had been spellbinding. The night before, at San Mateo’s Circle Star Theater, he had been brilliant, performing all the good stuff, and even reviving Mary Wells’s “Two Lovers,” one of Smokey’s best early songs, about a total schizophrenic, a man who was both lovingly faithful and totally amoral.

Gaye’s voice was soft, relaxed, and strangely monotonous (he spoke with almost no inflection). His precise elocution was reminiscent of your stereotypical English gentleman, but he spoke of a world far removed from delicacy and style. These were words of isolation, alienation, and downright confusion. His reviewed acclaim had in no way silenced the demons that made his last Motown album In Our Lifetime (despite its premature release by Motown) an explicit battle between the devil and the Lord for his heart, soul, and future.

“It seems to me I have to do some soul searching to see what I want to say.”

I said to him, “The times seem to call for the kind of social commentary you provided on “What’s Going On.”

“It seems to me I have to do some soul searching to see what I want to say,” he said. “You can say something. Or you can say something profound. It calls for fasting, feeling, praying, lots of prayer, and maybe we can come up with a more spiritual social statement, to give people more food for thought.”

“I take it this process hasn’t been going on within you in quite some time.”

“I have been apathetic, because I know the end is near. Sometimes I feel like going off and taking a vacation and enjoying the last 10 or 15 years and forgetting about my message, which I feel is in a form of being a true messenger of God.”

“What about doing like Al Green and turn your back on the whole thing?”

“That’s his role. My role is not necessarily his. That doesn’t make me a devil. It’s just that my role is different, you see. If he wants to turn to God and become without sin and have his reputation become that, then that is what it should be. I am not concerned with what my role should be. I am only concerned with completing my mission here on Earth. My mission is what it is and I think I’m presenting it in a proper way. What people think about me is their business.”

“What is your mission?”

Without a moment’s hesitation he responded, “My mission is to tell the world and the people about the upcoming holocaust and to find all those of higher consciousness who can be saved. Those who can’t can be left alone.”

A year later I reflected on those words while reading the comments of Rev. Marvin Gaye, Sr., Marvin’s father, from his Los Angeles jail cell. It had all gone wrong for Marvin since our talk. The physical assaults on others, including his 70 year old father, Marvin’s self-inflicted psychological degradation of himself with his “sniffing,” and the lack of creative energy it all suggested, meant Marvin’s unrest was real. Still, to me, the most frightening comment was Rev. Gaye’s response to whether he loved his son or not: “Let’s say that I didn’t dislike him.”

Summer 1958—Stardom was taking its toll on the Moonglows, one of the 1950s top vocal groups. One member had been hospitalized for drug abuse. Another was tripping on the glamour and the friendly little girls. Harvey Fuqua, the Moonglows’ founder and most level-headed member, was disturbed to see how the Moonglows were not profiting from their fame. It was during this period of growing disillusionment that four Washington, D.C. teens, called the Marquees, finally talked Fuqua into listening to them in his hotel room. Well Fuqua was “freaked out” by them, particularly the lanky kid in the back named Marvin Gaye. By the winter of 1959 two editions of the Moonglows had come and gone when Fuqua accepted an offer to move to Detroit as a partner in Gwen Gordy and Billy Davis’s Anna records.

That Fuqua kept Marvin with him is testimony to his eye for talent and the growth of a friendship that, in many ways, would parallel that of future Motown coworkers Smokey Robinson and Berry Gordy. On the surface Marvin was this seemingly calm, tall, smooth-skinned charmer whom the ladies found most seductive. Marvin was cool. Yet there was an insecurity and a spirituality in his soul that overwhelmed his worldly desire, causing great inner turmoil. This conflict could be traced to his often strained relationship with his father, a well-known minister in Washington, D.C. Rev. Gaye was flamboyant, persuasive, and yet disquieting as well. There was a strange, repressed sexuality about him that caused whispers in the nation’s capital. His son, so sensitive and so clearly possessed of his father’s spiritual determination and his own special musical gifts (he sang, played piano and drums), sought to establish his own identity.

So he pursued a career singing “the devil’s music” and in Fuqua found a strong, masculine figure who respected his talent. Together they’d sit for hours at the piano, Fuqua showing Marvin chord progressions. Marvin took instruction well, but his rebel’s edge would flash when something conflicted with his views. His combination of sex and spirituality, malleability and conviction, made Fuqua feel Marvin was something special. Marvin, not crazy about returning to D.C., accepted Fuqua’s invitation.

“I wanted to be a pop singer—like Nat Cole or Sinatra or Tony Bennett. I wanted to be a pop singer Sam Cooke, proving that our kind of music and our kind of feeling could work in the context of pop ballads. Motown never gave me the push I needed.”

Marvin never recorded for Anna records. But he sure met the label’s namesake, Gwen’s sister Anna. “Right away Anna snatched him,” Fuqua told Aaron Fuchs, “just snatched him immediately.” Anna was something. She was 17 years older than Marvin, but folks in Detroit thought she was more than a match for most men. Ambitious, shrewd, and quite “fine,” she introduced Marvin to brother Berry, leading to session work as a pianist and drummer. Later, after Berry had established Motown as an independent label, Marvin cut The Soulful Moods of Marvin Gaye, a collection of MOR standards done with a bit of jazz flavor. It was an effort, the first of several by Motown, to reach the supper club audience that supported black crooners Nat King Cole, Johnny Mathis, and Sam Cooke. It flopped and some were doubtful he’d get another chance. Yeah, he was Berry’s brother- in-law (that’s the reason some figured he got the shot in the first place), but Berry was cold-blooded about business.

Then in July Stevenson and Berry’s brother George had an idea for a dance record. Marvin wasn’t crazy about singing hardcore r&b. But Anna was used to being pampered and Marvin’s pretty face didn’t pay bills. Neither did a drummer’s salary. With Marvin’s songwriting aid “Stubborn Kind of Fellow” was recorded late in the month. “You could hear the man screaming on that tune, you could tell he was hungry,” says Dave Hamilton who played guitar on it. “If you listen to that song you’ll say, ‘Hey, man, he was trying to make it because he was on his last leg.’” Despite “Stubborn” cracking the r&b top ten Marvin’s future at Motown was in no way assured. He was already getting a reputation for being “moody” and “difficult.” It wasn’t until December that he cut anything else with hit potential. “Hitch Hike,” a thumping boogie turn that again called for a rougher style than Gaye enjoyed, was produced by Stevenson and his bright young assistant Clarence Paul. “Stubborn”’s groove wears better than “Hitch Hike”’s twenty years later, yet his second hit was probably more important to his career. Gaye proved he wasn’t a one-hit wonder. He proved too that the intangible “thing” some heard in Gaye’s performance of “Stubborn” was no fluke. The man had sex appeal. “I never wanted to sing the hot stuff ,” he would later tell David Ritz in Essence. “With a great deal of bucking, I did it because … well I wanted the money and the glory. So I worked with all the producers. But I wanted to be a pop singer—like Nat Cole or Sinatra or Tony Bennett. I wanted to be a pop singer Sam Cooke, proving that our kind of music and our kind of feeling could work in the context of pop ballads. Motown never gave me the push I needed.”

Cholly Atkins, Motown’s choreographer during the glory years, remembers things differently. “Marvin had the greatest opportunity in the world and we were grooming him for it,” Atkins says. “He almost had first choice to replace Sam Cooke when Sam passed away. He had his foot in the door. He was playing smart supper clubs and doing excellent, but it wasn’t his bag. He wanted to go on not shaving with a skull cap on and old dungarees, you know what I mean, instead of the tuxedo and stuff. That’s what he felt comfortable doing….But he has his own thoughts about where he wants to go or what he wants to do with his life. And he doesn’t like anybody influencing him otherwise.”

Beans Bowles, a road manager and Motown executive in the mid-60s, remembers Marvin as a “very disturbed young man … because of what he wanted to do and the frustrations that he had trying to do them. He wanted to play football. He tried to join the Detroit Lions.”

“I just love football. I love the glory of it … there’s an ego thing involved … and the glory is with the pros.”

In 1970, at 31, Marvin tried to get Detroit’s local NFL franchise to let him attend rookie camp. This was the period after Tammi Terrell’s death when he was, against Motown’s wishes, working on What’s Going On. Yet he was willing to stop all that for the opportunity to play pro football. Why?

“My father was a minister and he wanted me in church most of the time,” he told the Detroit Free Press. “I played very little sandlot football and I got me a few whippin’s for staying after school watching the team practice.” This parental discipline only ignited Marvin’s contrary nature and his fantasies. “I don’t want to be known as the black George Plimpton,” he said, somewhat insulted by the comparison. “I have no ulterior motive … I’m not writing a book. I just love football. I love the glory of it … there’s an ego thing involved … and the glory is with the pros.”

The Lions, not surprisingly, turned him down flat. Marvin’s attempt didn’t surprise those who knew him then either. At Motown picnics he always played all out, trying to outshine his contemporaries at every opportunity. One time he severely strained an ankle running a pass pattern. In Los Angeles in the early 1970s he developed quite a reputation as a treacherous half-court basketball player. He even tried to buy a piece of a WFL franchise in the mid-’70s.

There were two levels to Marvin’s often fanatical attachment to sports. One was a deep seated desire to prove his manhood, his strength, his macho, in a world where brute power met delicate grace in physical celebration. For all his sex appeal and interest in sexuality (“you make a person think you’re going to do something, but never do until you’re ready”), Gaye wanted to assert his physical superiority over other men.

Linked to this was a need for teamwork, a need to enjoy the fruits of collaboration. All his best work, be it some early hits with Micky Stevenson, Let’s Get It On with Ed Townsend, What’s Going On with Alfred Cleveland or Midnight Love with Harvey Fuqua were done in tandem with others. For all his self-conscious artistic arrogance, he was a team player. In the ’60s Marvin bent his voice to the wishes of Motown, but he did so his way, vocally if not musically. He claimed he had three different voices, a falsetto, a gritty gospel shout, and a smooth midrange close to his speaking voice. Depending on the tune’s key, tone and intention he was able to accommodate it, becoming a creative slave to the music’s will. On the early hits (“Ain’t That Peculiar,” “Hitch-Hike”) Gaye is rough, ready, and willing. His glide through the opening verse of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” is the riff Nick Ashford, the song’s co-writer and producer, has been reaching for all these years. On Berry Gordy’s “Try It Baby” Marvin’s coolly slick delivery reminds us of the Harlem bars I visited with my father as a child. His version of “Grapevine” is so intense, so pretty, so goddamn black in spirit, it seems to catalogue that world of black male emotions Charles Fuller evokes in his insightful Soldier’s Play. Listening to Marvin’s three-record Anthology LP will confirm that no Motown artist gave as much to the music as he did. If he had never made another record after December 31, 1969 his contributions to the company would have given a lasting fame even greater than that reserved for Levi Stubbs and Martha Reeves. But, as Marvin often tried to tell them, he had even more to offer.

“If one were to say that James Brown could be the Fletcher Henderson and Count Basie of rhythm and blues, then Marvin Gaye is obviously its Ellington and Miles Davis.”

In 1971, Motown released What’s Going On, a landmark that, forgive the heresy, is as important and as successfully ambitious as Sergeant Pepper. What?! I said this before Gaye’s demise and I still say it. Stanley Crouch, in a well-reasoned analysis of What’s Going On, explains it better than anyone ever has.

“His is a talent for which the studio must have been invented. Through overdubbing, Gaye imparted lyric, rhythmic, and emotional counterpoint to his material. The result was a swirling stream-of-consciousness that enabled him to protest, show allegiance, love, hate, dismiss, and desire in one proverbial fell swoop. In his way, what Gaye did was reiterate electronically the polyrhythmic African underpinnings of black American music and reassess the domestic polyphony which is its linear extension.”

Furthermore, Crouch asserted, “the upshot of his genius was the ease and power with which he could pivot from a superficially simple but virtuosic use of rests and accents to a multilinear layered density. In fact, if one were to say that James Brown could be the Fletcher Henderson and Count Basie of rhythm and blues, then Marvin Gaye is obviously its Ellington and Miles Davis.”

Though lyrically Marvin never again reached as far outside his personal experience for material, the musical ambience of What’s Going On was refined with varying degrees of effectiveness for the rest of his career.

Part of the reason for Gaye’s introspection was a series of personal dramas—a costly divorce from Anna, a tempestuous marriage to a woman 17 years his junior, constant creative hassles with Motown and antagonism with his father over religion, money, and his mother. Drugs became his escape hatch and his prison. As his In Our Lifetime so brazenly articulates, the devil was after his soul and damned if he wasn’t determined to win.

April 1983—Any purchaser of other Rupert Murdoch newstock publications knows the details of Marvin Gaye’s death. I expect the trial, if his father isn’t declared insane, to be an evil spectacle, full of drugs, sex, and interfamily conflicts. It won’t be fun. What was, and will always be my favorite memory of Marvin, was his performance of the National Anthem at the 1983 NBA Allstar Game. Dressed as dapperly as any nightclub star, standing before an audience of die-hard sports fans, and some of the world’s greatest athletes, Gaye turned out our nation’s most confusing melody, asserting an aesthetic and intellectual power that rocked the house. I play it over and over now. CBS was going to release it as a single. Don’t you think they should now?

From Shake It Up: Great American Writing on Rock and Pop from Elvis to Jay Z, edited by Jonathan Lethem and Kevin Dettmar and published in hardcover by Library of America. Copyright © 1984 by Nelson George. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

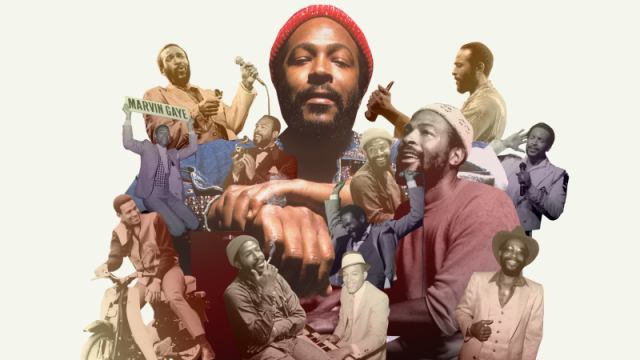

[Featured Illustration by Elena Scotti/Deadspin/GMG]