Leonard Chess had just turned forty. He had two children and was living on the South Shore of Chicago. Each new station in his life would be marked by a new house, a new office. It’s one of the places where the Jewish character and the American character bleed into one, this rootlessness, this urge to roam: how can you tell you are moving if the scenery doesn’t change? Leonard truly became Leonard only at forty. As a young man, he seems miscast, itchy in the too-tight costume of youth, a man who craves the authority of middle-age-papa, with his brood and mind made up and voice so much like the rumble of a bass guitar. Leonard fully realized: a man who knows when to shout and when to whisper; who, though balding, never attempts a comb-over; who, though graying, never attempts a dye, and wears bland suits and blah shirts and lets his eyes carry the weight of expression. A man who sits on his desk, folds his arms, lets his head roll back and says, “We take care of this problem now, or it takes care of us later.”

On his way to work, you could not pick him out from the crowd of nine-to-fivers. A face in a sea of faces, how could you know he hid among them like Oppenheimer, building a lab to split the atom. Coffee, donut, Sun-Times, galoshes. Leonard was a progressive in a (not really) progressive town; a Democrat in a city of machine-built Democrats. When he made millions, he would give it away by the tens of thousands to charity—that classic chow mein of Jewish philanthropy, half to Israel, half to everyone else, mostly blacks, NAACP, CORE. He might seem old-fashioned, a relic of the pre-Kennedy, hat-wearing era, but he was in fact a true modem, a pioneer in a business as new as the Internet is today. In this, he followed a long tradition of Jews who sought their fortunes in the brand-new thing, often in that place where show biz intersects with technology. It was the age of the Jewish photographer, the Jewish filmmaker. Such men placed their faith in progress because what did they have to be nostalgic for, because show me an invention and I will show you a way to get rich, because a new technology is inevitably followed by a new industry that has not had time to build the barriers to keep out men like Leonard Chess.

For Leonard, this was an era of long days, the sort well known to our fathers and grandfathers but not to us. He would spend seven, eight hours in the office, or in the studio, or hustling distributors, then head to the Macomba, which he had mostly left for Phil to run. The life of the club owner was something Leonard left behind, the noise and violence drifting into lore. In 1948, Charles Aron, co-owner of Aristocrat, divorced his wife, Evelyn. Leonard, with ten grand borrowed from his father, bought out Charles Aron’s share. Leonard now had a stake in the gold mine. He was an owner. A capitalist.

So what kind of a record man was Leonard?

“I never during all those Chess years looked upon my father or my uncle or myself as artists,” Marshall Chess told me. “We were businessmen trying to make it. My father wanted to make what black people wanted to buy. We were not out to make great music. We were out to make hits, to make money. And that’s what the artists wanted.”

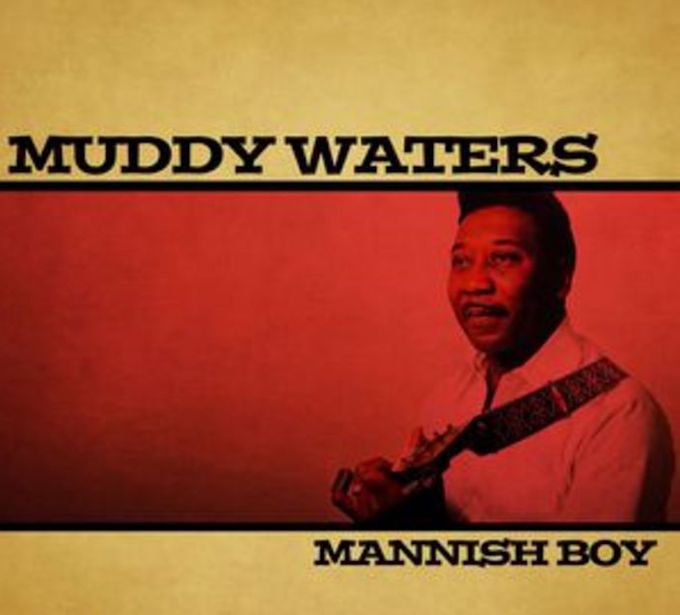

Up to this point, he had flown on the prevailing winds, producing flat jazzed-up blues that sounded like everything else; records that came and went like wind across the sand. Fire-spotting trends, anticipating the next break in a wave, talent scouting his way up the charts (shit, shit, shit, hit, shit)—these were not Leonard’s skills. He was no genius. He did not dazzle into the big score. He instead had to work for it, fake it, steal it, copy it, shuffle and fight. He was smart and tough in the way of the hard worker, the long-distance runner, the gambler who wins on stamina. In business, and probably in art, too, such men have the advantage over the genius, who depends on the great big nothing, a fluky, unpredictable freak. One day it’s there and one day it’s gone back to whatever nowhere it came from, and you are like the card sharp who bets on instinct when his luck runs out, with no way to fake your way back into the game. But for the hard worker, it is a fake from the beginning, and so he’s developed a million tricks and bluffs to get through. Leonard could not spot a song, something he was criticized and mocked for, but he had a skill far more important: he could spot the man who could spot the song, woo him and hire him, and then, when the gift goes away, dump him like an aging wife. It was not music Leonard had a talent for—it was people. A bloodsucking skill because, if done right, it means, in a business sense, never growing old. Willie Dixon would serve as the key man in the glory years, but in the beginning, it was Sammy Goldberg. And it was Goldberg who, one day when a musician did not turn up for a session, remembered the kid he had met in the union hall: Muddy Waters.

“I never during all those Chess years looked upon my father or my uncle or myself as artists,” Marshall Chess told me. “We were businessmen trying to make it. My father wanted to make what black people wanted to buy. We were not out to make great music. We were out to make hits, to make money. And that’s what the artists wanted.”

When the call came, Muddy was out on the truck—he had a job delivering venetian blinds. The relative who took the message got in his car and raced around the city looking for Muddy, another moment so crucially cinematic you imagine it in storyboard: jagged lines, narrow streets, the big truck tearing around a corner. When Muddy got the message, he ran to a phone and called his boss. He said his cousin had been found dead in an alley and he had to rush home. This lie is the original sin on which Muddy built his career—OK, not a deal with the Devil, but still pretty graphic and ghetto-y in a way meant to titillate the white boss. So here comes Muddy, and this guy walks like John Wayne, a soldier back from the war, a farmer in the rain, drenched but not about to hurry. His first recordings were a classic case of trying too hard, aping the Bluebird beat. In the second or third session, after he had burned up considerable tape and money, and the patience of Leonard was wearing thin—and as a Negro from the South Muddy could always sense the loss of patience in a white man—he figured, Fuck it, if I fail at least I will fail as myself, and launched into some old Delta Blues. This is the moment the needle, after popping and hissing, falls into the groove and the music blasts away a song that will play for the next thirty years. Two sides came out of the session: “I Can’t Be Satisfied” and “Feel Like Going Home,” basically the same songs Muddy had recorded for Alan Lomax.

Leonard did not get this music. Every time Muddy sang a verse, Leonard would ask, “What is he saying? What the fuck is he saying?” He would ask this in the same way that, on trips in the Toyota Celica, when I played my tapes, usually by the Clash or R.E.M., but also the Alarm and Mojo Nixon and Tom Petty, my father would slap the dashboard and say, “Where in the name of Sweet Pete is the melody?” This was just before my father replaced my tape (“Road Mix Two”) with Sinatra’s “Old Blue Eyes Is Back,” saying, “Now that’s music!” Or: “When Frank says, ‘The summer went so quickly,’ he is not talking about the summer, he is talking about life. It’s life that goes so quickly.” And then Leonard said, “Who’s going to buy that?” This question, unlike, “What the fuck is he saying,” or, “Where in the name of Sweet Pete is the melody,” would soon be answered to Leonard’s satisfaction.

When the record was cut, Leonard kept it on the shelf. Muddy came in week after week to ask when it would hit stores. Leonard said, “Patience” or “Give it time” or “Wait your turn.” Over the years, this became the habit at Chess. If Leonard was your boyfriend, you would call him commitment-phobic: he recorded and recorded but seemed never to release. He blanched when it came time to plunge, invest the money, press, and distribute. A record would spend years in larval form as an acetate, the big waxy master from which copies were made. For every four songs recorded, maybe one was put into production. To suspicious artists like Bo Diddley or Jimmy Rogers, it seemed a form of control, with the songs held as hostages. Leonard said he was in fact protecting his investment, guarding the reputation of his artists by only releasing quality—an assertion scoffed at until Leonard died and many of those shelf-bound originals were released. In 1997, Jimmy Rogers told Living Blues magazine, “I hear some stuff they released on Muddy Waters, it’s terrible, man. I made lots of stuff. I hope they don’t ever release it.” At times, it seemed Leonard was awaiting a portent or an omen. He tended to rely on oracles. Sonny Woods, who worked in the stock room, would listen to each new cut, saying, “This ain’t shit” or “Put that motherfucker out.” When Sonny Woods first heard “High-Heeled Sneakers,” he said, “Let’s get it on the street.” And also, those random individuals, like the blowzy neighborhood lady who was standing out of the weather under the front awning when Leonard put on the acetate of Little Walter’s “Juke.” The music drifted through the rain and the woman started to clap her hands and dance. The record was rushed into production.

But these songs by Muddy—no one had ever made commercial records like this. It was music from the underclass, the language of rent parties and cotton fields. Who the fuck is going to buy that? In the end, it was not Leonard who had the guts to press and release—it was Evelyn Aron. She was in the business less for the money than for the connection to the real, and these songs were real. It was Evelyn who pushed Leonard to release that first record by Muddy. “Evelyn was the one who really liked my stuff,” Waters said. “Leonard didn’t know nothing about the blues, but Evelyn, she really got it.”

For the first generation of rock stars, hearing these blues was a revelation. “It changed everything,” Eric Clapton told Rolling Stone.

A few thousand copies of “I Can’t Be Satisfied” were released in the summer of 1948. “This was old deep Delta Blues, no doubt, but it was also something new,” Robert Palmer writes in Deep Blues. “It stood out amid the glut of sax-led jump combos and balladeers because of its simplicity, passion, and hypnotic one-chord droning.” Of course, with songs, as with people, context is everything. The passage of time can diminish or enhance a song, or change it into something else. A tune that was crap when new, like “Wang Chung,” returns years later as a time capsule, which, if it catches you unaware, will knock you out. For a few weeks you revel in it, feeding off its flavor of the past, until you bleed it out like gum and so bring it back into today, where once again it’s crap. Songs that, on first release, were good but probably not mysterious, like early George Jones or Johnny Cash, are remade by time into hints of a vanished America, spooky in the way of old photographs. “In Dreams” by Roy Orbison was surely excellent when new but could not have carried that charge that sends the malaise needles deep into the red. Other songs are diminished by time, and this is often the case with the blues, which have been so ripped off and imitated they’ve become almost impossible to hear. Time has made them into background noise, like a ragtime tune used in a documentary about the Jazz Age, so you must really work to hear them as they sounded in those first years, the novelty and charge and sex and dirt of them. How strange to hear “Feel Like Going Home” in 1948 after years of the bland pop on the Hit Parade. “The first guitarist I was ever aware of was Muddy Waters,” Jimi Hendrix is quoted as saying in Crosstown Traffic: Jimi Hendrix & Post-War Pop, by Charles Shaar Murray. “I heard one of his early records when I was a little boy, and it scared me to death.”

It was this music that would set up the collision between poor blacks and middle-class whites that would result in Rock & Roll. For the first generation of rock stars, hearing these blues was a revelation. “It changed everything,” Eric Clapton told Rolling Stone. “Muddy was the first person that got to me and his is still the most important music in my life.” For those who loved the music but could not play, these records drew forth that cataract of articles and books that suggests a cultural shift—wherever you see a cloud of paper, something big has happened. The music ushered in a super dorky school of music writing, educated white guys picking apart the thoughts and lyrics of poor black guys. Here is John Collis, in his book Chess Records, summing up the plot of the Muddy Water’s song “Louisiana Blues”: “The singer is yearning for Louisiana as an escape route from his troubles and to equip himself with a ‘mojo hand’ to ensure greater sexual success.”

Leonard placed Muddy’s record in stores across the South Side, in groceries and beauty salons and newsstands, where he hoped people would recognize Muddy’s name from the dives. This is the part of the story where I am supposed to say this record, which the boss did not want to release, a record without precedent, made by a mostly illiterate black man (Muddy could sign his name) who, until a few years before, lived in a shack on the edge of a cotton field, became a surprise, runaway hit—and so it did! On the morning of its release, when Muddy walked to Maxwell Street to buy a copy, he was told, because the record was selling so fast, customers were allowed only two copies. Muddy bought two and sent his wife back for two more. There was no radio, no advertising, no nothing. It was word of mouth. Leonard had stumbled upon a vast reserve: over a hundred thousand blacks from Mississippi who craved their own music. For everyone else, it was a change in the weather, an appearance of the real, Brando mumbling in a movie. It was like that commercial: she told two friends, and she told two friends, and so on, and so on. The record sold out by the end of the first day. Leonard pressed thousands more. He did not analyze this success or take it apart—he simply did what good merchants do: played out the string, not caring why it worked, just glad it did. He stayed with it until it redefined him: switched the label from sophisticated blues to a down-home sound. Leonard was now the impresario of Delta Blues, music sold to the poorest people in the city. He began signing the artists, most of them from Mississippi, who would turn his company into a powerhouse: Robert Nighthawk, Robert Little John, Little Milton, Clarence Gatemouth Brown, John Lee Hooker. Muddy’s record went on to sell over sixty thousand copies, many more than any other record ever released by Aristocrat. It reached top twenty in Billboard.

For Muddy, it was a strange sensation. Fame. As if he had cast off an image that had gone on to live a life of its own. What did it have to do with him? Late one night, he was driving alone through the city in his new convertible, the streets shut down and the windows dark and the dark towers like a distant line of hills, and that warm wind that blows all summer, and he heard a sound so forlorn and familiar he pulled over and sat for a long moment listening before he realized it was his own voice, his own song, floating down from the dark apartments above. “And it really scared me,” he said. “I thought I had died.”