“Gilbert, my God, you look great!”

“Jesus, Gilbert, that suit looks amazing on you.”

“It’s the suit they gave him on the Cosby Show!”

“Gillie! I got hold of the Cinemax special—it’s, it’s … beautiful!”

“Gillie, who’s doing your hair? It’s fabulous!”

Oh, baby, there’s no business like it. At the moment, the business is outside Studio 6A, awaiting the taping of Late Night With David Letterman. Ego boosts are flowing around Gilbert Gottfried like Thorazine in a psychiatric emergency room. Two years ago, when Gilbert first appeared on Late Night, he arrived at NBC alone, hung out in the greenroom by himself, went on, did his set and went home. Now he’s surrounded by a genuine show business entourage. But then, entourages always materialize around a star, and make no mistake about it, Gilbert’s “people” are absolutely positive that Gilbert is “three months—four, tops!” away from being a big star.

“He’s going to be huge.”

So, okay, why? Why should Gilbert suddenly be a “can’t miss” after years as a “near miss”? After all, he’s been a relatively obscure comic for sixteen years, lasting just one season as a regular on Saturday Night Live and even less on Thicke of the Night. Granted, he’s a kind of inside legend—“the comic’s comic”—whom his peers call “a stand-up genius” as they quote his bits like English professors dissecting King Lear. And, yes, many comics see him as infinitely more brilliant than Robin Williams, who, some say, has “borrowed” portions of Gilbert’s material. (Gilbert says only that Robin is reputed to be “absorbent.”) But still you wonder, Who are all these people, and why are they draped all over Gilbert Gottfried?

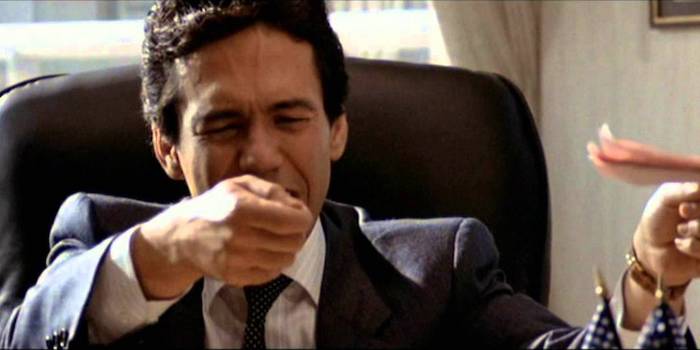

The curious thing about Gilbert’s people is how maternally they treat him. Then again, there is something childlike about him. At 32, he’s a slight five feet six, with thick black hair: the Hebraic Corazon Aquino. And wearing that sharp suit, which, with the help of a few jokes, he persuaded Bill Cosby to let him keep, he’s a guy to make any entourage proud. Agents, producers, secretaries, flacks and makeup artists treat him like the lovable, amusing kid of the family: coddling him, complimenting him and then coaxing him into doing his impressions of other comics—Cosby, Richard Belzer, Jerry Seinfeld—mimicry so dead-on, it’s almost eerie. The entourage howls. They seem to be grasping their son one last time before pushing him into the real world. You wonder, Is he headed for stardom or college?

“Stardom! He just did a Cosby Show, a Cinemax special, and he’s in Beverly Hills Cop II. He’ll be huge in three months—four, tops!”

When Letterman goes onstage, Gilbert heads for the greenroom. On a couch behind him is another guest, actress Heather Thomas. God, is she ever blonde! Who needs these distractions when you’re a Jewish kid raised in captivity (a.k.a. Brooklyn) and just about to perform on the hottest talk show in America?

Gottfried goes on ahead of Thomas. Does he sneak a last peek at her? Maybe a tiny one. He hits the stage and his body turns into one spasmodic synapse. In an autistic frenzy, he faces the audience but makes no eye contact. His hands grab at his face as if he’s hemorrhaging. His stage voice is loud and guttural—like that of a crotchety middle-aged New Yorker with a hearing disorder who just assumes everyone else is equally deaf.

He opens by telling the audience how much he envies their chance to sit and watch him. “OOOH, WHAT A TREAT FOR YOU! I ENVY YOU! OOOOH, HOW I ENVY YOU! OOOH, HOW I ENVY YOUR LIVES!”

He’s like a mutant version of a borscht-belt “shticktician.” Many in the audience laugh, others look around, figuring this is another of Letterman’s surreal gags.

Suddenly Gottfried switches gears. His voice quiets to 110 decibels.

“I had dinner the other night with Charles Manson. In the middle of the meal he said to me, ‘Gilbert… is it hot in here or am I crazy?’”

Letterman is helpless at his desk. Bandleader Paul Shaffer, America’s barometer of hip, is roaring. Back in the greenroom, Heather Thomas is in a blonde laughing fit.

After the show, Thomas comes up and asks him for an autograph. Gilbert is shocked. With the jittery hand of a man writing a suicide note, he scrawls, “To Heather, Best wishes, Gilbert Gottfried.” He wonders if someone taller, or Waspier, could cash in on this situation.

Instead, in the next few minutes, Gilbert will say goodbye to Heather Thomas. To Late Night staffers, William Morris agents, PR people from a comedy club. He’ll get in a Late Night-provided limousine and direct the driver to Avenue A on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, a timeworn zone of the city, where the star-to-be lives in an apartment with his mother, on the other side of the world from the glitz he’s just left behind.

A day after the Letterman taping, Gilbert sits for lunch at a midtown restaurant, peels off his coat, sweater and vest, then launches into a perfect David Brenner impression: “You know when you’re in a restaurant, who decides where the napkins go? C’mon! It’s crazy.”

Aside from the never-ending jokes, Gottfried looks waif-like, right down to his sneakers, which seem rescued from Woolworth’s must-go bin. To be funny is all the ambition Gilbert seems to have. The other attendant aspects of show business seem to just hem in on him. Take that entourage of his. “I don’t know what most of them do,” he says, looking puzzled. “I stand around and say, y’know, ‘I’m going to the watercooler for a drink,’ and one of them says, ‘No, I’ll get that for you, Gilbert,’ and that’s how I find out what they do.

“James Dean once said to me, ‘The key to this business is longevity.’”

“My biggest problems are, like, standing around for an hour in a store deciding whether to get waxed dental floss or unwaxed. That’s what I really need people around for. Going onstage and doing comedy is one of the few things I can do for myself.”

Gottfried is being about as straightforward as he gets about himself. Ambivalence is his theme song, and if enigma makes an entertainer that much more compelling, Gottfried may exceed his entourage’s wildest dreams. Discussing his life, career, comedy—anything—is something he almost pathologically avoids. Ask him a serious question: “Do you have any deep ambition in show business?” Watch him ponder the question. Assume he’s on the brink of a thoughtful reply. Hear his answer: “James Dean once said to me, ‘The key to this business is longevity.’”

Try another: “Have people told you you’re self-destructive?”

Beat. “Sylvia Plath once told me to lighten up.”

Though he’s loath to admit it, Gilbert has friends. Most are comics. Try to get some clues about him from them and they all mention what a good-hearted person he is. Then they talk about his quirkiness—how he’s never had a driver’s license, or how he’s so cheap that at 2 A.M. on frigid nights he’s been seen waiting for a bus home.

Finally, they all admit to being in the dark about his personal life. All they have is a grapevine of psycho-babble theories—most of which include the adjective “neurotic,” often preceded by the adverb “deeply.” Magnificently alienated artist? Idiot savant? Hopelessly self-destructive in his career moves? One comic says, “My feeling is that Gilbert is a brilliant comic, but he doesn’t play the game. The feeling among some of us is ‘He’s had his chances. He should be a star, but he’s not, so fuck him.’”

What a week.

First Gilbert has a part on The Cosby Show. Then it’s Letterman, followed by six shows in four nights at New York’s hippest comedy club, Caroline’s, where five of the sets will be recorded for an album. Sprinkled in are a slew of commercial auditions and a taping of some more of those MTV promo spots he’s been doing to such acclaim.

Is Gilbert excited about all this? “I try not to pay any attention,” he says. Excuse the blasé attitude. He’s been through all this before.

Gottfried was one of Saturday Night Live’s seven regulars in 1980, the year after the last of the original cast had left and Jean Doumanian had taken over from Lorne Michaels as producer. As the season went on, Gilbert, never one comfortable with performing other people’s material or sitting down to write in groups, was involved in fewer and fewer sketches. “Toward the end, I played the part of a corpse on one show,” he says ominously.

When Doumanian was fired late in the season, Dick Ebersol took over and told Gilbert not to worry, that he was giving the cast some time off and would then meet with all of them. On the day of the meeting, Gottfried got a fan letter from a midwestern girl who wrote him frequently. It started off, “Dear Gilbert, I’m really sorry about what happened….”

That’s how Gilbert Gottfried found out he had been fired.

Immediately after, Gottfried went back to playing gigs at Manhattan’s Catch a Rising Star. According to club regulars, his act was temporarily erratic, featuring Gilbert making feedback sounds and doing obscure impressions that had audiences walking out in droves. The comic’s comic was naturally using his act as a vehicle to express his anger.

Three years later, on Thicke, the show’s producers wanted Gottfried to do a short set every night. Gilbert, unwilling to burn up so much material on one program, refused. At the end of the season, the producers let him go.

Many comics say that if Gilbert had adapted or compromised a little more he’d have made it big off either Saturday Night or Thicke. Their attitude is, if you blow such opportunities, you don’t really want success. The same is true for Gilbert’s inability to find a manager who can guide his career. (He hired and fired his most recent one within the first three months of this year.)

“Fun? Who has fun? Nobody has fun.”

Nowadays, Gilbert can laugh off the Thicke experience. As for Saturday Night, he insists, “Much to people’s dismay, I was neither elated when I got on Saturday Night or devastated when I was fired. People say, ‘Gilbert really flipped out when he was fired from Saturday Night,’ but I think it happened long before that.” He laughs at his own joke. “That’s a good quote, isn’t it?”

It was wailing on MTV that brought Gilbert Gottfried back to life. Bob Pittman, originator of MTV, is now producing Gilbert’s album. His first exposure to Gottfried was when MTV was looking for a radical departure in its promotions. MTV executives called Gilbert, gave him an idea of what they wanted and let him wing a series of brief, manic spots ideal for him: He could scream at an invisible audience that demanded no eye contact. The spots met with wildly unexpected reaction. “Ad agencies were calling us all the time, asking, ‘Who is that guy?’” recalls Pittman.

One thing quickly led to another. Says Stu Smiley, head of East Coast comedy programming for HBO and Cinemax, “I saw Gilbert’s MTV spots and thought it was the first time he was really effective on television. So I went to see him perform at a few clubs and decided we had to do a Gilbert special.”

Bill Cosby, meanwhile, had liked Gottfried’s work on Thicke of the Night and had recommended him for TV roles in the past. Then one night Cosby spotted Gottfried on MTV and told his casting people to get Gilbert on his show. Gottfried’s episode aired the night of a blizzard on the East Coast and wound up the highest-rated sitcom half hour in American television history.

“What was amazing was that Gilbert was one of the few people who constantly made Bill crack up on the set,” says Cosby co-executive producer John Markus. “Then one day I went up to Gilbert on the set and asked him if he was having fun, and he said, ‘Fun? Who has fun? Nobody has fun.’”

So how was Gilbert’s experience on Beverly Hills Cop II?

“Oh, that was fun …,” he says with mild conviction. The impact of Gilbert’s small but concentrated role, which he totally rewrote, is being compared to that of Bronson Pinchot’s in Beverly Hills Cop.

Comedian Richard Belzer doesn’t see Gottfried as freakishly hot for no reason. “Gilbert was always ahead of his time,” says Belzer. “He never adhered to any commercial winds. Before this new wave of ‘character comics,’ like Sam Kinison, Bob Goldthwait and Emo Philips, there was Gilbert. He’s become commercial without ever changing. The times have caught up with him.”

If Belzer is right, if the times have caught up with Gilbert, why is there so much talk among other comedians of Gilbert’s blowing it, of his somehow finding a way to finesse his way out of success again?

Perhaps it’s because if there’s any place where Gottfried does exhibit self-destructive tendencies, it’s onstage, where he regularly commits stand-up sacrilege, like coming up with brilliant bits that he, inexplicably, never performs again. Or seemingly having no awareness of audiences. Or doing a six-minute impression of an obscure character actor, such as Howard Da Silva.

For his part, Gilbert says, “I think doing Howard Da Silva is selling out. He’s too well known.”

Gottfried on being self-destructive: “To me, self-destructive is driving a car off a bridge. As far as comedy goes, one person’s view of self-destructive isn’t necessarily mine.” On being aware of audiences: “I’m sure Laurence Olivier is aware of the audience when he does Hamlet, but that doesn’t mean he says, ‘To be or not to be,’ then looks into the audience and says, ‘Hey, buddy … nice tie.’”

As for audience response, Gilbert refers to a bit in which he’s talking with Charles Lindbergh, who says, “Gilbert, y’know, it’s so hard to get a good sitter these days.” Gottfried says the joke “gets lots of groans. It’s surprising how many people are still sensitive about that Lindbergh baby. Lots of times, I do the joke and someone says, ‘That’s it, honey, get your coat. We’re leaving. He did a Lindbergh baby joke.’” Truthfully, Gilbert can recall only one time when he really offended someone in an audience. In the late Seventies, he was onstage reading from the Bible in a voice one would use for a trashy sex novel. A tall black woman stormed out of the room. It was Donna Summer.

“You know, this week I’m going to be on The Cosby Show and soon I’ll be appearing in Beverly Hills Cop II with Eddie Murphy.”

The audience at Caroline’s cheers for Gilbert’s successes. He raises his voice. “You would think at this point in my career, at least one white person would hire me! Why don’t white people want to work with me? I’m now being billed as ‘the funny Jew for black shows.’ What, phone call for me? Who? Nipsey Russell? Great, I’ll be right over! What? Another call? Stu Gilliam.…?”

The Caroline’s shows are pure Gilbert, unrehearsed and untamed. He opens one set by shouting, “Stop staring at me! Please! Stop staring at me! I don’t go to your job and stare at you!” The next night, he reacts to the opening applause by blaring, “Stop it! Stop it! Please, stop it! Please! Did I say ‘please’? Yes, I said ‘please.’ So just stop it! You’re getting giddy! And when you get giddy, the next thing you know, you poke someone’s eye out. Then you have dinner with that person and you say, ‘How’s the chicken?’ and the guy says, ‘What about my eye?’”

“You would think at this point in my career, at least one white person would hire me!”

He sets up a bit in which he’s in the middle of a field when a spaceship lands. Thousands of greenish-gray aliens surround him and stare. Finally the leader says to him, “Ben Gazzara. He’s a good actor. Why can’t he get a series?”

In another set, he swerves into an ad-lib off the same bit, talking about how shocked NASA was when men landed on the moon and failed to find Zsa Zsa Gabor leading a race of moon girls in silver miniskirts.

NEIL ARMSTRONG: “Uh, hello, NASA? There’s nothing up here!”

NASA: “You’re on the moon?”

ARMSTRONG: “Yeah, yeah, where else am I gonna call from?”

Later, Gilbert says the bit just hit him, so he ran with it. His onstage confidence is so fireproof, he regularly does an alter-ego character named Murray, an old man who does nothing but criticize Gilbert’s jokes. Gottfried puts on huge eyeglasses, bares his upper teeth, and, in an immigrant’s voice, “Murray” says, “That’s funny? Ahhh, I don’t see the humor. I mean, Zsa Zsa Gabor on the moon? She’s never been there! Wha- what kind of joke is this?”

Gottfried began working Manhattan comedy clubs at 16, having never considered college. He says he’s never been influenced by any one comic (“Influence is a polite word for plagiarism”) and can barely point to one he really admires. Mention names and he’ll roll his eyes or say, “He never had an original thought in his head.”

Though Gottfried’s sets are wrought with tragic references—Kent State, Manson, the Lindbergh baby, Nazism, John Kennedy’s assassination, Kurt Waldheim, the Reverend Jim Jones—Gilbert denies any overly serious motivations behind an act to which he gives “not much focused thought.”

But if there’s any insight into Gottfried’s soul, it came in a talk with Stu Smiley while they were filming the Cinemax special. “Just before the shoot,” says Smiley, “I was talking to Gilbert about this other comic, and he said to me, ‘Judging by that guy’s act, you’d never know there was a Holocaust.’”

The more popular Gottfried becomes, the more people will dust his psyche for fingerprints trying to find where he’s been touched. His secretive homelife always winds up the main focus. You feel as though you’re dealing with a comedic Norman Bates.

His two-bedroom apartment is in a twenty-one-story high rise in the Alphabet City section of New York, where middle-class families mix with unbridled punkers, gentry with crack dealers. Small shops are boarded up day by day, one after another. Huddled masses of the elderly who have lived there for decades schlepp groceries home, their darting eyes wary of the area’s virulent “bad elements.” In nice weather, they sit outside the building and say to Gilbert, “You’re the TV star, no?” Gilbert usually says, “No, it must be someone who looks like me.”

He goes up the elevator and walks quickly through cold, thick-walled, stark hallways. The building, which houses a cultural cross section, is well kept but no-frills. In mid-afternoon, wafts of cooking seep under doors, mingling into a heavy smell of clashing ethnic cuisines.

“I think Hogan’s Heroes is The Pawnbroker with a laugh track.”

When Gilbert reluctantly allows someone in his home, he seems a hybrid of fragility and ego—first ushering you around with monosyllabic nervousness, then proudly showing tapes of himself and articles he’s written for National Lampoon.

His widowed mother, a familiar voice on the phone to Gilbert’s showbiz contacts, is sweet and friendly as she welcomes you. She’s a small, gray-haired woman whose slight waddle is reminiscent of her only son’s (Gilbert has two older sisters). People who talk about Gilbert’s “good heart” would melt at the tenderness with which he treats her. Still, he won’t let her be interviewed, and besides, she’s never seen him perform live anyway. (“I don’t know why … she was supposed to see me once, but she had tickets for Howie Mandel.”)

The apartment seems to have a time-warped sepia tone. Old furniture is haphazardly arranged, like in a congested antique shop. Everything is functional, not decorative. Worn chairs abut cabinets overflowing with knickknacks, all of which converge on Gilbert’s bed, positioned for the optimum view of a color TV and a VCR, the only reminders that you’re not touring a museum of 1930s domesticity. Gottfried says he spends many nights in this spot, watching old movies and sitcoms. Sometimes both: “I think Hogan’s Heroes is The Pawnbroker with a laugh track.”

Writer Betsy Borns has pondered the sight of Gilbert in front of this TV in this home she’s never seen. In writing a book on comics, she’s become “as friendly with Gilbert as is humanly possible.” She finds that “he’ll make obscure references, and you think he’s so knowledgeable. Then he’ll badly mispronounce a reference, and you get the feeling everything he knows has been read or learned from old movies.”

Gilbert says that after a great set at a place like Caroline’s, he can sometimes understand the allure of drugs. Something to keep that feeling of invincibility. Instead, it will be more midnight hours in front of the television’s blue light, sitcoms and movies filling his eyes while he sits on the bed, surrounded by an unframed photo of himself arm in arm with Jerry Lewis at the Montreal comedy festival, and an autographed picture of Heather Thomas.