Glenn Stout, a longtime favorite here at Bronx Banter, is most famous around these parts for his historical writing, particularly Yankees Century and Red Sox Century. Stout also serves as the series editor for The Best American Sports Writing; his oral history Nine Months at Ground Zero is one of the most fascinating and devastating things I’ve ever read about 9/11.

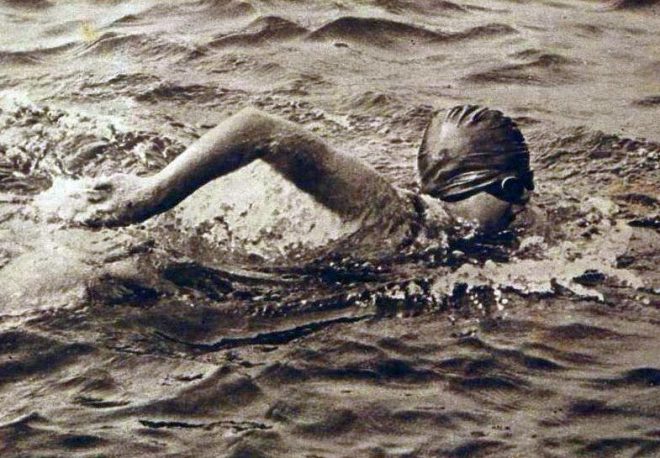

Stout has a website as well as a blog, and his latest book, Young Woman and the Sea: How Trudy Ederle Conquered the English Channel and Inspired the World, may be the most interesting project of his career. It is the story of Trudy Ederle, the first woman to swim the English Channel (read an excerpt here).

I had the chance to talk to Stout about the book.

Alex Belth: I know you are comfortable writing about history, especially in the first part of the 20th century. What drew you to Ederle?

Glenn Stout: Her story is seminal, as central to the story of American sports in this century as that of Red Grange, Babe Ruth, Jack Johnson, or Jackie Robinson. Yet to most people, Trudy, aka Gertrude Ederle, is unknown. I wanted to change that. In many ways she was both the first modern female athlete and one of America’s first celebrities. Had she not done what she had done, which is not only to become the first woman to swim the English Channel but in the process to beat the existing men’s record by nearly two hours, the entire history of women’s sports would be radically different.

You can, I think, break down the history of women’s sports in this country into “Before Trudy” and “After Trudy.” Before Trudy, female athletes were anomalies, and their accomplishments, with just a few exceptions, primarily took place out of the public eye. Many early female athletes, like Eleanora Sears and Annette Kellerman, were sometimes seen as publicity hounds who performed stunts and not serious athletes. The question of whether or not women were either psychologically or physically capable of being athletes was still a topic of debate—at least by the men who ran sports. Although there would still be some who would stubbornly cling to that belief, by swimming the English Channel and shattering the existing men’s record, Trudy answered that question quite definitively.

She was the answer. One can argue that had it not been for her women would not have been allowed to compete in track and field and many other sports as early as they did—women competed in track events for the first time at the Olympics in 1928. It may have been another generation—until after World War II—before there was any acceptance of female athletes. I am old enough to remember when women could not play little league, or run marathons, and when school sports were pretty much limited to gymnastics and basketball. Now of course, women can and do play everything. Without Trudy that happens much later than it did.

Trudy also has a compelling personal story that I think resonates with any reader. She grew up in New York, the daughter of German immigrants, and overcame anti-German prejudice in the wake of World War I to become arguably the most famous woman in the world. At the same time, she was partially deaf and was able to overcome that challenge. Swimming the English Channel, while perceived to be somewhat commonplace today, is still extremely difficult—it was the first “extreme” sport. More people have climbed Mount Everest than have swum the Channel, and most of those who try to swim the Channel fail. In most years more people will succeed in climbing Everest than in swimming the Channel. When I first began to research the book, that really, really surprised me and made Trudy’s story even more compelling.

Alex: Why isn’t Ederle remembered like Grange, Thorpe, Ruth, and the other greats of the first great era of sports? For someone who had such a profound impact, why has her legacy faded?

Glenn: Hopefully, my book will help rectify that, but there are several reasons. Trudy herself soon discovered she just wasn’t cut out for the spotlight. Within 48 hours of her return to the United States, where New York gave her an enormous ticker-tape parade, she was in the fetal position in her bedroom, completely overwhelmed. She was both slow and reluctant to “cash in” on her achievement. Her attorney mismanaged her career, turning down easy money for a grueling vaudeville tour. By the time that got going a male swimmer had broken her record and a second female swam the Channel, which stole some of her thunder—the public began to think that swimming the Channel was far easier than it is, something that holds true today.

She also had increasing trouble with her hearing—she was partially deaf since a bout with the measles as a child, and that made her less comfortable in the public eye. And a few years after the swim she fell and was virtually bed-ridden for a time. And let’s face it, swimming simply isn’t a big spectator sport like football or baseball.

Alex: What is Ederle’s reputation in the world of women’s swimming? Is she properly recognized?

Glenn: Swimming historians certainly recognize her as one of the all-time greats, but in a sport like swimming, records have been broken so many times that it is difficult for any swimmer from her era to remain in the public eye. Her only contemporary recognized by the public today is Johnny Weissmuller and that’s because of the Tarzan films. But in the world of swimming, she has to rank as one of the top seven or eight swimmers of all-time. No one else combined her success at shorter distances with open-water success, and in the world of open-water swimming, I think she’s right at the top. Anyone who has ever swum the Channel, or thought about it, knows about her.

Alex: How did Ederle manage to beat the existing time of swimming the channel by such a great margin? That seems almost inconceivable.

Glenn: There are a couple of reasons. For one, she used a stroke known then as the “American Crawl” essentially what most people recognize as the “freestyle” today. Her coach with the Women’s Swimming Association was one of the stroke’s pioneers and its greatest advocate. And although it had been used for about two decades, no one believed it could be used for long-distance swimming—it was thought to be too demanding, physically. Long-distance swimmers usually used the breast stroke at the time, with occasional use of the side stroke and trudgen. The crawl was much faster, and Handley recognized that women in general, and Trudy in particular, although not as strong as a man, had just as much stamina. She was the first swimmer to use the stroke in the Channel and proved the superiority of the stroke.

Secondly, her trainer for the Channel swim, William Burgess, was a real student of the Channel currents and tides, and he found a somewhat new route across that was something of a breakthrough. Also, before Trudy, most of the people who tried to swim the Channel simply were not great swimmers. They had great stamina and desire but as swimmers were rather pedestrian. Trudy was world class at every distance from fifty yards on up. She was simply a far, far, far better swimmer than anyone else who had swam the Channel before. For a swimmer of her ability to take on the Channel would be the equivalent of Michael Phelps doing so today—if he had her stamina.

And lastly, while Trudy was growing up she spent summers in Highlands, New Jersey, where she spent hours and hours swimming in the ocean. She developed a very special relationship with the water, once saying “To me, the sea is like a person—like a child that I’ve known a long time. It sounds crazy, I know, but when I swim in the sea I talk to it. I never feel alone when I’m out there.” When she was swimming, she was in her place, right where she wanted to be, and where others found only torture, she found joy; and when you love what you do, well, there are no limits.

Alex: Can you share the story about the tragic boat fire that helped lead to changes in the way Americans thought of woman and swimming?

Glenn: In the summer of 1904 nearly 1,500 German immigrants, mostly women and children, were aboard the steamship General Slocum going from lower Manhattan to Long Island for a picnic. It caught fire and the boat captain ran the boat aground on North Brother Island in the East River. But despite the fact that the boat was only a few yards off shore, in relatively shallow water, over 1,000 passengers died—most by drowning. A terrific book called Ship Ablaze tells the whole story.

As I write in Young Woman and the Sea, it was “murder by repression.” Women were not allowed to learn to swim and that is what killed them. Had they been able to swim most would have survived. Not until 9/11 did more New Yorkers die in a single incident. But in the wake of the tragedy some women’s groups began advocating for the rights for women to learn how to swim. That provided the impetus that led to Trudy’s accomplishment twenty years later.

Alex: Describe the Victorian attitudes toward women and swimming.

Glenn: In short, you weren’t supposed to swim if you were a woman. It was considered risqué and sexually provocative. Moreover, most medical and athletic experts—all men—felt that women simply were not physically able to compete in any sport, including swimming. It was considered too taxing, and women were not supposed to be strong enough to swim. The few that tried had to be covered from head to toe—wear woolen leggings and a long skirt and a swimming shirt that left only your head, face, and hands uncovered. Even when standards relaxed somewhat and the Women’s Swimming Association, of which Trudy was a member and which pioneered women’s sports, started holding meets in the late teens and early 1920s, women were still getting arrested on beaches around New York if they exposed their calves.

Alex: Having written a biography, I have a great deal of admiration and respect for historians who can bring their subjects to life, especially when none of the participants is living. What are the narrative challenges that you faced in trying to achieve this?

Glenn: That was the challenge of the book: How do you animate a subject and her accomplishment, particularly one that took place more than eight decades ago, and one that most people have probably never heard of, in a sport that—let’s face it—does not easily lend itself to narrative? How do you make those fourteen and half hours she spent in the water into a compelling story?

To do so I felt I had to give her story the proper context and tell several stories at once—the geology and history of the English Channel itself, the history of swimming, the history of Channel swimming, and the history of women’s athletics, as well as Trudy’s own personal story. Of all the books I have done, this clearly provided the most difficult structural challenge. What I ended up doing was to begin the book using sort of an “alternate chapter” structure. In one chapter I tell part of Trudy’s story—her background and upbringing, for instance, or how she learned to swim—and then in the next chapter I’ll tell a piece of one of those other stories, like how the English Channel was formed and why that makes it so difficult to swim, or the story of Matthew Webb, the first person to ever swim the Channel. My goal was slowly to bring those stories together so they intersect when Trudy enters the English Channel, at which point the reader has all the information he or she needs to appreciate it and accompany Trudy on her journey. It has been incredibly gratifying to learn from readers and reviewers that I managed to pull that off.

But the central story of the book is the actual swim itself, which I tell over two chapters. From the outside one might expect that just entails putting one arm out in front of the other for hours and hours and hours. But it is not. Although swimming the Channel isn’t like telling the story of a baseball game—there are no innings when swimming the Channel—there is a similar unfolding of an event over time. I was able to plot the story quite specifically by using the “bulletins” the press sent out by wireless from the press boat that followed her across. In that way, in effect, I was able to put “innings” in the story of her swim and find moments of drama, clarity, and insight. I think I was able to deliver the dramatic tension in the event through both the changing weather conditions in the Channel, the changing mood on her escort boat, and in her own mood and physical condition. Once again, readers have really responded to this in a very positive way. Several people who have swum the Channel themselves have read the book and told me that I captured the experience.

All of that, of course, is built from research. I read everything I could possibly find about her, the Channel, the history of swimming, and women’s sports at the time. I watched films, looked at photos, read blogs and diaries and stories about other swimmers. I immersed myself in 1920s fashions and music and slang. Writing a book like this is like building a brick wall. Each fact is a brick—and you have to have enough bricks—so each snippet of information you find becomes extremely, extremely important. If you say it’s raining, you better have looked at the weather report. For the weather on the day she swam the Channel, I got the official report from the National Meteorological Archive of the British Weather Office. Let me put it this way: I think I did more intensive research in this book than I did in any of my big baseball books, like Yankees Century or Red Sox Century, even though those books are twice as along and cover much longer time spans.

Alex: In the back of the book you mention that you spent a good chunk of time in the water yourself. How did that experience help inform you about Ederle?

Glenn: It was absolutely necessary because I needed to be able to translate accurately that experience—to “get it right.” I’ll admit that I am not much of a swimmer, but I do live on Lake Champlain near the Canadian border in northern Vermont and from April through November have the opportunity to either be in or on the water. Now Lake Champlain isn’t the English Channel, but it is a sizable body of water, and for much of the year it is cold. So I made sure I got in the water and spent some time in it when the water temperature was about sixty degrees, the same temperature it was for Trudy. Obviously, I can’t swim for nearly as long as she—and it wouldn’t be safe for me to try to do so—but I did spend an hour once in the shallows, dog paddling till I got tired running in place with only my head sticking out.

I also spent hours and hours and hours kayaking on the lake in all sorts of weather conditions, including some that I probably shouldn’t have, to gain some understanding of what it is like to negotiate the water in three- or four-foot waves, both against and with a 20-mile-per-hour gale, with an air temperature of about sixty degrees, for five or six hours, while it is raining. Kayaking isn’t swimming, obviously, but it does put you on the water, and when you are several miles off shore you become keenly aware of the fact that you alone are responsible for getting back to shore—people die on boats out here every year, so it’s no joke. I often took trips of ten or fifteen miles—five or six hours—just to experience these conditions. Even on a good day, you have to stay mindful of where you are, what the weather is doing and how you are feeling. There just isn’t any room for other thoughts, and at a certain point the battle to continue becomes more mental than physical, an experience Channel swimmers know very well.

I think it helped that much of my other athletic experience includes solo sports. I’ve been a runner for thirty years so I have some insight into the mental experience of doing physical activity while by yourself, and I’ll even include the time I spent pitching in adult baseball leagues or pouring concrete as a construction worker as a part of that. It’s just you out there, and that’s the way it was for Trudy. Again, several Channel swimmers have told me straight up that I “got” the experience. That means a great deal.

Alex: You mentioned that you put yourself at potential risk on the lake doing research. Did that have a beneficial effect on the writing or at least your understanding of the perils of the water?

Glenn: Absolutely. Trudy’s swim took place during a storm and I had to understand what that meant. I don’t want to overstate things, but I tried not to put myself at peril. In really bad weather, I’d stay close to shore when I could, I always wore life vests and carried safety equipment, and I never intentionally went out in lightning or anything like that. I also used a very stable, “sit on top” kayak, which is very difficult to flip. But that being said, anytime you are out on the water alone, you get an immediate understanding of the risks that entails—I’ve had boaters tell me they would rather be on the open ocean than in Lake Champlain during a big storm.

I think it was important for me to gain some understanding both of that and of what it is like to perform the same physical activity for hours and hours. My longest kayak trip, in terms of time, was about eight or nine hours, and while that is clearly not the same as swimming, I think paddling that length of time without stopping provided me with some insight into the psychology that allowed Trudy to swim for fourteen hours and helped in the re-creation of that experience in the book, both on the sensory level and descriptively.

Alex: Did you pattern the narrative on anything that you’d read before? In doing this kind of book, did you read anything to “put you in the mood”?

Glenn: I read a great deal of nonfiction in my work as series editor of The Best American Sports Writing, and I’ve always been a big reader of nonfiction. Most helpful to me, structurally, was probably Eric Larson’s Thunderstruck, which simultaneously told the story of a murder and Marconi’s invention of the wireless, which was used in the capture of the murderer. He told multiple stories that came to together over the course of the book. So do I, so it was helpful to see how another author did that. Specifically, however, I didn’t really model the book after anything or read anything specific to “get in the mood.” In a book like this, the reading you do in your research—primarily contemporary newspaper accounts—tends to get you there; you are already immersed in a time. But it also helped that in so many of my other books, in particular the four big baseball histories, I’ve already had to write about the 1920s and, more specifically, the 1920s in New York, so there was some familiarity already there.

Alex: What is the trickiest part about re-creating scenes and situations? What is it like, both aesthetically and ethically, for a writer?

Glenn: You owe it to the reader to, as much as possible, re-create the experience, to make it live. That is the aesthetic challenge. You can’t expect people to spend six or seven hours of their time reading a book and be bored. But regardless, the short answer remains the same: You don’t make anything up, you don’t create dialogue, and you don’t put a thought in anyone’s head that is not informed by the facts. Too many books and too many writers have recently gotten in trouble for that, and it is just not worth it. Besides, it is cheating, and taking a shortcut, and if you have done the research and the work, you shouldn’t even have to fight the impulse to make anything up—you should have enough information already. The truth always makes the best story.

Where you can and have to be creative is in the way you combine that information, how you layer it upon your subject and take something that is one- or two-dimensional and make it three-dimensional. I’ll give you an example. In my proposal for the book I described the color of the water as Trudy viewed it while she swam—she was wearing amber-tinted goggles, and I knew from my own time in the water, when I put the lens from an old pair of sunglasses in a face mask, that this would make the water appear not green or gray, but as I described it, a “golden ochre.” But as I worked on the book I could not find a specific statement from her about this, so even though I was certain I was right, I took it out. Then, when I was working on my final draft about the swim, I was double-checking my research one last time and there it was, one line in an interview in which she did mention the color of the water. I had been right, so I put it back in.

In another instance, I was struggling to write about how it looked for her as she approached Kingsdown Beach—she landed in England after dark, and I knew there were bonfires on shore and flares in the sky and searchlights scanning the water, but I didn’t know if she noticed them—was she too exhausted to care? Did it make an impression? Again, she herself provided the best description, telling one interviewer that when she first lifted off her goggles, it looked like a child’s fairy story, a fairy tale. Now, when I use those impressions in the book I don’t stop the narrative to reference it directly in the text to those interviews like an academic book would, but those impressions are factual. That’s how it should work.

But you are only as good as your information, and there are places where you have to use your own best judgment. Multiple accounts about the same event rarely line up in all areas—even the quotes will sometimes be different. In those instances you try to create a composite. Or if you have one account that differs radically from others, you have to use your own intellectual judgment to weigh the veracity of the evidence. For example, at one point in her swim someone on the boat yells for her to “Come out, girl, come out of the water!” But no two stories phrase it exactly the same way, so I created a composite. But no story identified the speaker, either. It was very tempting for me to do so, but even though I have my own thoughts on the matter, I didn’t have enough evidence to make me feel comfortable doing so, so I leave it as is, simply as “someone.” Besides, she probably could not hear well enough at the time to know exactly who called out to herself, which is probably why she never identified the speaker.

But she knew how to respond. She asked, “What for?” And that’s the crux of the book right there.

[Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons]