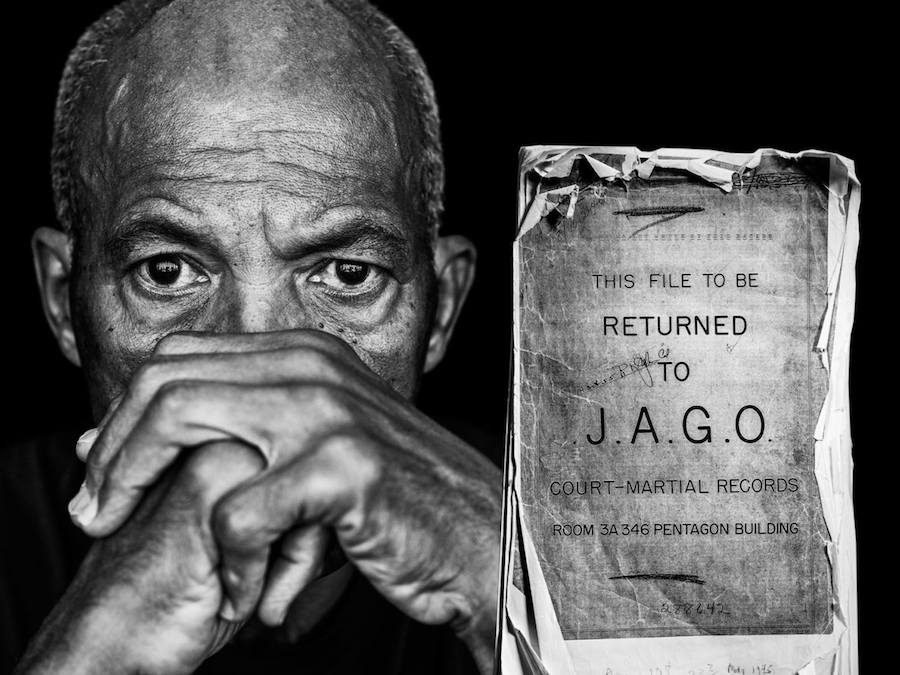

The story of Emmet Till is embedded in our public consciousness as one of the most notorious hate crimes of the century. What is lesser known—and what novelist John Edgar Wideman tackles with candor and humility in his haunting new meditation, The Louis Till File—is the story of Till’s father, who was executed by the U.S. Army in 1944 for reportedly raping and murdering a local woman in Italy.

The book, which is excerpted in our current issue, is less than 200 pages and written in plain-spoken prose, but it is a dense, challenging read. The language is succinct yet there is still a good deal of space—white space on the page, philosophical space—too. The book is a fascinating blend of reportage, memoir, and fiction. Wideman knows about fathers and sons and in searching for Louis Till he moves closer to understanding his own father, and, as he explained to us recently over a glass of wine at an outdoor café on the Lower East Side, perhaps even himself.

Alex Belth: The first piece you wrote for Esquire was a short story about a blind man playing pick-up basketball—“Doc’s Story.” How did that come about?

John Edgar Wideman: I wrote that story as a kind of doffing of my cap to James McPherson, who wrote a story about railroad porters, “A Solo Song: For Doc.” I really liked that story. One of the characters was named Doc, but for me, I was just exploring that territory—men my father’s age, the jobs they had to take, the porter jobs that enabled them to raise their families and have some dignity and have some independence. In the case of railroad porters or waiters, they were able to travel and see the world and live in more than one world. I remembered all those sorts of things from his story and thought about how one of those characters would be on the basketball court, transferred into my world.

Alex: Had you ever written about basketball before?

John Edgar: I don’t know if I ever wrote about it as explicitly before so it was a breakthrough in that sense.

Alex: Had you read John McPhee’s New Yorker profile of Bill Bradley at Princeton in 1965 when it was published?

John Edgar: No, not until much later. Bill’s a couple of years younger than I am and we’ve become good buddies over the years. We played against each other at least on four occasions. He was a sophomore when I was a senior [at Penn]. Everyone knew he was great, one of the best players in the country but he hadn’t quite broken through that magic ceiling yet. Depending on your mojo you either thought Bradley was the best or Cazzie Russell was the best. Like an early version of Magic or Bird. Anyway, Bill was at Princeton and then I knew him at Oxford. We played together on the same team at Oxford—it was my last year there and his first. And then we just kept up.

Alex: You spent three years at Oxford. Did you feel any more at home abroad than you had in the States?

John Edgar: I don’t think so. At the time I grew up I never felt like I lived in the country, exactly. It was always like what Baldwin said—Another Country. I didn’t feel more at home in England. I felt very much at home in Pittsburgh, P.A., on my block, with my people, on the playground. I was quite aware of the larger society, of the good old USA, that all of my smaller worlds were part of. My worlds were plagued by, deceived by, or in a way antagonistic to the larger world. They intersected in ways too, particularly with sports. And language. Oxford for me was a chance to sit and catch up on reading that I had not been able to do in college. A lot of reading.

Alex: You eventually returned to writing about basketball in your journalism. I love your 1990 profile of Michael Jordan because it captures him right before the Bulls started winning championships.

John Edgar: They were still losing to Detroit. The thing I remember about that assignment was how long I had to travel to get to the Palace in Auburn Hills. Through millions of miles of suburbs. And then, it was all white people in the stands. There I was, and there the black guys on the court were, and that was about it. That was quite a strange experience. The other thing I remember distinctly about it was how much fun it was to walk in with the team and be talking to guys and be mistaken for a retired player and make no attempt to disillusion anybody. Then hanging out after the others had gone in to get dressed and still taking that in, that nice vibe of being one of the guys.

Alex: You got a minor injury in a pick-up game the day before you flew to Chicago to interview, which spoiled any chance of you shooting around with Jordan. Was that part of your original plan?

John Edgar: Michael had been playing a shoot-around game and it had been raining and the game was not finished and he insisted they finish, that someone win or lose—of course he wanted to win. They played on the court after it was wet and he just tickled his knee. Enough to scare the shit out of him. So he wasn’t playing any ball outside of the game. I always thought it was lucky that he didn’t have to meet me on the court (laughs) and also I was pissed that I didn’t get to do my George Plimpton thing. Me and Mike, one on one. That was kind of in the back of my mind. I liked him. He was a good dude.

Alex: Basketball also figures in your profile of Denzel Washington when he was filming He Got Game. He comes across as being involved in life outside of his career—sports with his kids, being with his extended family. Did that come across to you?

John Edgar: He believed what he was saying, I think. He was sincere. I got along well with him. He was just ready to peak in terms of fame. In fact, this was the second time I saw him. The first time I met him was when Spike Lee was doing Malcolm X. I was writing about it for a magazine and it got me out of the country, and gave me some bucks and got me on a movie. I’d never been on a movie set. I hung out with Spike Lee and went to Egypt. That was all great fun. First time I met Denzel was in a mosque. It was early morning and the light was quite brilliant outside and it filtered into the mosque in these particular spaces in an organized way. I’d been on a plane traveling for ages, I was in Never-never Land myself, zonked out. I go into this almost candlelit very wide-open space with light coming from a great height. A guy, very far away, at the other end of the building, walked in and he had a nimbus of light around him and he looked otherworldly. He could have been a person, could have been a Mullah, a spirit. He’s pacing, bowing a little bit, taken by the physical beauty of the place. I don’t know who this character is and it turns out to be Denzel Washington.

We talked from that point on about the movie and about his character. He was also having fun in the experience of almost channeling Malcolm as he was playing Malcolm, particularly in that environment because he knew so much about Malcolm’s life and Malcolm’s trip to Mecca. It was interesting for us both. I felt I was on a kind of pilgrimage. I’d never thought a lot about Islam so it was my introduction to a whole different spiritual world. And my introduction to movies. All of those things hitting me at the same time.

Alex: In your Esquire profile, Denzel talks about his father dying. One day, Denzel tells him, “You’ll be okay.” And the old man looks at him like, “Are you kidding, boy?” In the Louis Till book you write a lot about your father. Was the relationship between fathers and sons on your mind when you began the book?

John Edgar: Oh, I think very much so. I had the simple, visceral flash—Emmett Till had a dad, just like I had a dad. Those simple words I said to myself numerous times. It was a generational thing, locating Till, and thinking of how he related to his father, the Army, my father and the Army, WWII, and it all started to come together. It crept up on me that it would be impossible to write about Till without writing about his father so therefore I had to write about my own father since it was my relationship to Till that eventually became the center of the book.

Alex: What was your initial concept of the book?

John Edgar: I had forgotten the father/son relationship in that story. Not only had I forgotten, it had been severed—by history, by time, by the forces of racism in our society. I realized that in many ways black boys weren’t supposed to have fathers. In the public imagination we didn’t have fathers. We were wild things and maybe that’s one of the things that was wrong. We didn’t have white fathers, anyway, and we needed white fathers even if they were slave masters. That’s what we needed to grow up, to become men, to become real human beings. And the absence of those fathers was a wound. There was no way the young men could heal. Me. No way I could heal that because it was out of my hands.

Everybody’s father is taken away by a job, by work, competition with the mother, so there’s that gap anyway, but for young men of African descent that whole business was encrusted by outside layers of interference, outside violence, outside attempts to obliterate or falsify the relationship between father and son. It was used against us so often that we even shied away from it in the most basically biological sense. My skin is brown so I must have a brown father. But brown men aren’t worth shit so what’s that make me? [Points to his skin] Is this color shit-brown? The whole paternal link is problematized. Systematically so. And this is true for any poor kids in a working class family, where the father is drawn out of the house. If he’s really trying to support the family he probably has more than one job and when he comes back he’s probably beat to shit, if he gets back. If you’re going to do two jobs, when is your shift at home? When the kids are asleep or at school. These are systemic ways that separate. Separated me.

Alex: And yet your father was a presence in your house even when his absence served as a kind of presence, right?

John Edgar: He was an intermittent presence in the sense of living in the house or not. Sometimes my father lived in the house, sometimes he didn’t. There were stretches—of years, even—when the family lived with grandparents, and my father was a visitor. And there were other times when he was around.

Alex: How did that affect your sense of waiting? Were you anxious? Or did you just accept it as the way things were?

John Edgar: I had to learn to play it as it went. I had to learn to make do with what was an unfortunate situation. There were other people who took his place, other people who did the jobs he was supposed to do, including my mother doing double-time as support, offering love. But I had aunts and uncles; we had a strong extended family. I had strong grandfathers. And my father wasn’t trying to escape from us. He made his presence felt. He wasn’t happy about what was going on, he just wanted his independence, he wanted his own life. We both made do with a bad situation, and it often wasn’t that bad. I wasn’t crying, I wasn’t waiting up at night for him to come back. There might have been certain times I missed him. I always wish he had been more part of my athletics in school. I was a very good jock. Everybody knew me. People came to see my games. But my father seldom did. He wasn’t the one I wanted there most but I wanted to prove something to him, I wanted to show him. He was, after all, a man. I can’t remember him saying “Sorry, I’m going to miss the game.” He wasn’t apologetic. He was busting his ass. Games were games. What are you gonna do?

It didn’t seem very often like something was missing but another part of me was aware that there was something missing. I knew that my father had been a pretty good playground player. People would say, “You Wideman’s kid?” I played guys he played with. Maurice Stokes and Ed Fleming went to the pros from the Homewood playgrounds. And my father schooled them. He was an old head who beat them up when they were coming up. And then I got to play against them, and they were the pros. They both knew me and took me under their wing and kicked my ass.

I don’t want to make this a bleeding heart story but I was deeply aware that my father was a special person I didn’t exactly know what relationship he was supposed to have to me, nor I to him. Nobody sat down and explained that. I didn’t have a hell of a lot of models for it. I didn’t know how it was in other people’s families. A lot of my friends didn’t have fathers around. Some did. Some had asshole fathers who were around; some had these church people fathers. Even those guys had a certain kind of distance in their family relationships. They got along better with other church members or the guys they played cards with than they did with their kids. Our time would come. When we got to be men we would know more what men did.

Alex: Did that make you want to grow up faster?

John Edgar: No, not particularly. I wanted to have what adults have. I wanted power, I wanted women—that was part of power—but you know, depending on the questions you’re asking and the way I’m thinking about them I realize that all these issues are unsettled. I don’t have a line on them. As I wrote the Till book, or as we’re sitting here talking now, they are never resolved. There’s no story to tell. There are many, many stories. Ask me questions, they open up other questions.

I ask myself questions and I think that’s a healthy way to be. There’s something human that has to do with time and space and being who I am that is in progress and always will be in progress. And who I am, on different days, different moments, depends on different aspects of my past. To be alchemized in a way that I need it at the moment, in the same way that countries and cultures make up history. Who the hell knows what happened? We all know there was a Civil War, we all know there was an institution of slavery, but to what degree does any person really attempt to come to any deep understanding of those events or those traditions? I think the more you do it the more you find out that you’re making it all up as you go along. Everything is made up as you go along. And other people are making things up as they go along.

The war started in 1861 at Fort Sumter. Great. Put that down and it’ll get you into college but now wait a minute. Was I there? Was Till there? And in a funny way my book touches on that. So therefore I’m there, in a certain fashion, and his son Emmett is there. That was a real insight for me. That I could take this person that I was imagining and I could put him almost anywhere. And if I did, there was a kind of chemistry, excitement, and creativity.

Alex: What you are talking about—fiction possibly being closer to truth than facts—is something you address specially in the book.

John Edgar: Everything is up for grabs, everything is relative. Except nothing is if you are serious about it because the moment you become serious about answering a question you have a stake in it. Relatively goes out of the window, in one sense because you’re putting your ass out there—you are depending on the answer, you need the answer.

Alex: Do you embrace the uncertainty more now?

John Edgar: I think I was blessedly innocent [when I was younger]. I thought whatever I thought made sense. There’s nothing like making a jump shot, feeling on top of the world, running back up the court on your toes, and somebody comes up behind you and—boom—either by accident or on purpose. Then you realize the game’s not over.

Alex: You certainly have dealt with a series of particularly dramatic blows in your own life—what happened to your brother and to your son would be enough to floor most people.

John Edgar: Oh, yeah. The hardship, the pain, the suffering of my brother and my son in prison, that’s absolutely their experience, that’s not mine. I don’t get any credit for enduring that. I never give myself any credit for enduring that.

Alex: Because you think you’d be taking something from them or that it would be self-aggrandizing?

John Edgar: No, because it separates me from them. In a funny way, it’s their experience but it’s also mine. I sometimes can look at someone on a bus, and look down at their shoe, and suddenly I’m inside that shoe. I get a sense of that person’s life, the whole texture of their life, and it sends a shiver through me. I’m not being compassionate, I’m not showing humanity towards them, I’m just them, man. I get a vibe from them. And this is something that has always been part of my life. It doesn’t happen often and I’m also very hard-nosed and cold-blooded and I can walk past a drowning man. If I have someplace else to go, well, tough shit. I could do that. I can. Have. Sometimes, not because I was callous but had to do it.

What do you do when a guard says “Time to go?” You’re visiting your son in prison and the guard says, “Time to go,” and you leave. If I had my way, I would grab a gun and turn the place inside out, okay? But I got to walk out. I have to deal with that. I can’t take everything of myself out of that visiting room but I have to take enough to get me to the parking lot and the next thing. So that’s what I’m talking about. And that’s incessant. That’s something I learned from my father. I’m sure that Emmett would have learned more of that from Louis Till had his father been around. That probably would have made him a very different person if he had survived. To pass from boy to man, he would have looked for some man to do that for him if Louis wasn’t around, or he would have had to do it for himself. And that’s called growing up. He didn’t get a chance to do that.

Alex: The book is short but dense. How long did it take to write?

John Edgar: Probably wrote something about Louis Till ten years ago for the first time. I did a nonfiction piece, did some research. I didn’t decide to write this book until about 2007. So, it’s been awhile. I didn’t know where I was going with it. The book is, in a sense, the record of thinking about writing it. My own process of discovering why I needed to write it and what it could be. That’s what made it interesting for me.

Alex: Are you pleased with how it turned out?

John Edgar: Yes, I am. Of course you always think writing a book will change your life.

Alex: You mean how well it is reviewed, how it sells?

John Edgar: No, not in that sense. Not that it will get you something concrete but this sense that everything fails, this pessimisim of being human, being vulnerable. When you start out on a book, you’re hoping that when you finish you’ll be different. How different? What different? If you knew that you wouldn’t need to write the book. You can’t say. Just that you are going to be a different person. That is hope in its most amorphous, shimmery, vaporous sense, but I think it’s part of the artistic urge. To write something, to make a piece of music, you really think you are going to change the world.

You’re not a new person when you’ve finished a book. The world hasn’t changed. But it’s not bad that you were able to sit down and do it. And it’s not bad that it ends. Then you try to sit down and do it again if you get the urge, if you can stretch yourself and make the leap.

[Photo Credit: Alexei Hay]