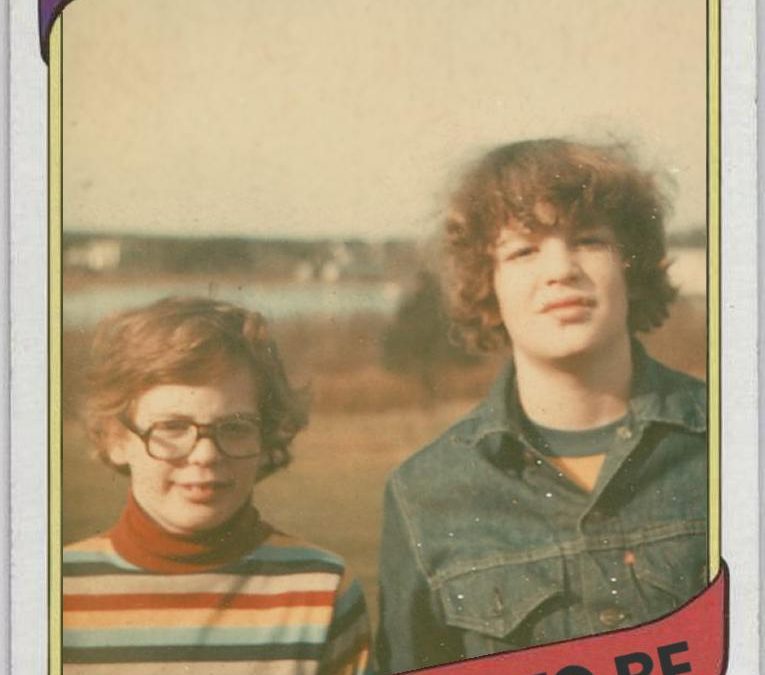

Every so often, you run into a kindred spirit, a guy you aren’t envious of, just proud to know. Todd Drew was like that, and so is Josh Wilker (pictured above, on the left with his brother Ian). When I first read Josh’s work at Cardboard Gods, I was thrilled. He had a strong voice, wonderful sensitivity, an unassuming sense of humor, and the courage to dig deep, way below the surface. I’d want to belong to the kind of club that would have a misfit like that as a member.

And I’m not alone. Josh’s long-awaited memoir, The Cardboard Gods: An All-American Tale Told Through Baseball Cards, has generated some great buzz and strong reviews. Josh hits the Big Apple tonight—he’ll be at the Nike Store in Soho from 7:30 to 9:30. He’s here through early next week and we’re happy to have him around.

I got a chance to chat with Josh recently and here is our conversation. Enjoy.

Alex Belth: Dude, first thing, what were your favorite kinds of packs to get when you were a kid? The single pack? Remember those triple packs that would be clear packaging with three little sets side-by-side?

Josh Wilker: I’m a single-wax-pack guy. The clear packaging ruined some essential part of the fun for me since you could see the top and the bottom card in the stack. It was better that it was a total mystery.

Alex: Bro, how deep does your nerdiness run? Do you carry a card around with you in your wallet?

Josh: I don’t, but I usually have a card that I’m working up an essay on in the pocket of the nap sack that I lug to and from work. And a couple summers ago when I came to New York to—among other things—go to Shea Stadium for the last time, I made a point of carrying an Ed Kranepool in my pocket every day of the trip.

Alex: Nice. Do you ever feel any attraction to modern baseball cards?

Josh: I just wrote a piece for GQ.com, of all places—considering my unstudliness—on the 2010 Topps cards. I bought a couple packs for the piece and got a charge out of it, and though the cards mostly left me cold for being too slick, I admired the high quality of them. The photos and the back of the card text is light-years advanced beyond the rudimentary nature of the 1970s cards, which may be why the new cards leave me cold. There’s no homely humanity in them.

Alex: Can you at all relate to the generation of kids who bought cards for what they might be worth one day, instead of being important for more personal reasons, or just ’cause they were the things to have, trade, and flip?

Josh: I can relate, I guess. I mean, when I was a kid, I fantasized that one day my Butch Hobson and Frank Tanana cards would be worth millions, so it’s not like the idea of the cards being “investments” was completely foreign to me. I was just too lazy to actually pursue that angle. I did feel like things were taking a wrong turn when I noticed, in the late 1980s, that the cards my younger cousin was collecting were going immediately into protective plastic. You have to be able to touch the cards, otherwise what’s the point?

Alex: When you started the Cardboard Gods blog did you have it in your mind to write a book? Or did that develop later?

Josh: My first intention was to play around and to keep writing and to maybe connect with some readers. I’d been working on a novel for several years previous to starting the blog, and I wasn’t able to sell it, and I was wary of signing on for another several years of solitary toil only to have the end product of the work end up at the bottom of a drawer. But I also thought it could be a book, too, from very early on. It was not unlike the first time I saw my future wife: a feeling like, “Hmm, I think there might be something here.”

I held off for quite awhile on trying to start shaping the material into a book, a tendency that has in the past had a way of crushing the life out things before they have a chance to grow. Instead I just tried to keep having fun and churning out material. After a while, I knew I had enough stuff for a book, if I could ever pull it all together into something coherent.

Alex: So, let me get this straight, you only write about cards from your collection, not the cards you missed from those eras, right? Excuse me if I haven’t caught it, but have you written much about cards you coveted but never actually got?

Josh: That’s the idea, though I have also occasionally written about cards that have come to me since childhood, most often cards that I find on the street, which I seem to have a gift for. My collection of cards from the 1970s has not grown since I was a kid except for when a friend sent me a 1979 Mark Fidrych card and when a kindly reader sent me a Rowland Office card after I complained in a post that I was convinced I once owned it.

Alex: So were you just riffing on topics as cards came to mind or did you know that certain stories were going to be attached to specific cards?

Josh: At first the idea was to reach in and pick a card at random and then try to start writing about it, about the details of the card and about whatever memories or fantasies it happened to suggest. I actually pulled all my cards out of the rubber band team stacks I’d had them in since childhood and shuffled them all together to promote this randomness.

But then I started getting ideas about certain cards or players and seeing ways in which certain cards or players connected to my life, and I ended up sorting all the cards back into their stacks so that I could find something when I needed to. My wife helped me sort them, which was a highlight of my life … I could feel the lonely pubescent kid inside me screaming: “A real live girl is helping you sort your cards!” I still periodically draw a card at random, especially if I’m feeling like I have nothing left to say.

Alex: Your wife helped sort your cards? Did you touch yourself while she was doing it? Did she have her own system of cataloging or did she follow what you told her to do? The erotic possibilities of your wife touching your Pete LaCock is almost too much to bear.

Josh: It didn’t really go in that direction, except in my fantasies. My wife likes organizing things—which is good for our life together, since I am a slob—and so when I tried to grab her as she was dutifully helping me divide all my cards into teams, she shrugged me off and said what I would have said as a kid if someone had tried to grab me during that process: “Not now, I’m sorting.”

Alex: You mentioned the desire to interact with an audience instead of being locked in a room with your thoughts. How quickly did you develop a readership and what effect did they have on your writing?

Josh: For a while, I didn’t even tell anyone about the blog. Then, after I got a few posts up I sent an email to some friends and family. Somehow, Darren Viola at Baseball Think Factory found one of my posts a couple months in—a Mario Guerrero essay that alluded to a Twilight Zone episode about a town called Willoughby—and put up a link to it and a few more people started visiting. Several months after that, a move of Cardboard Gods to the late, great Baseball Toaster group-blog site upped the readership, thanks to all the fans at the other blogs there, including, of course, Bronx Banter.

Being on Baseball Toaster was my favorite time so far in the life of my blog, because of the feeling of being in a fairly tight-knit community of smart, literate baseball fans. Having those kinds of readers paying attention and chiming in with their own great stories about growing up with the game, as well as correcting or expanding upon any factual errors or slights, definitely inspired me to work harder on the stories I was trying to tell. But I also found I had to learn to forget any potential readers, too, and write like I had just pulled the first card from the shoebox and was starting brand new in my room alone.

Alex: Interesting. It can be a trap to be overly influenced by the awareness that you’ve got an audience. Did you ever find that a particular post or story got positive attention and that became, not something you didn’t appreciate, but something that you were cautious about in terms of repeating yourself?

Josh: I can’t remember if I’ve ever felt that way about repeating a post that got a positive reaction, but I worry about repeating myself all the time. I used to worry about that more, actually, wondering if I was telling anecdotes that I’d already told, but after a while I decided to follow in the footsteps of one of my storytelling heroes, Howard Stern, who has been circling back around to his childhood and adolescence on a daily basis for decades, and just try to keep telling stories about the past that seem to have some vividness and sincerity in the present.

I also lean on a supposedly more highbrow influence in the constant return to my past—the poet Rilke once said something like the world of one’s childhood is something a writer can take an entire lifetime to explore.

Alex: Do you ever worry about running out of stories about your childhood or that there are a finite amount of cards in your collection from which to choose? Or like the quote from Rilke suggests, do you think this is a topic that you won’t exhaust for a long time?

Josh: I think I’m actually in a state of constant near-exhaustion, and I’ve felt that way since about a week into the whole endeavor. No joke, I remember writing about Otto Velez after about only three or four posts on the first location of my blog and thinking “That’s it, I’m completely out of things to say about baseball cards and my life.”

But I kept trying and will continue to keep trying to show up and see what’s there. I don’t have a huge collection of cards, compared to a “real” collector, but I still have enough cards to last me for years to come, maybe all the way to the graveyard. So I’ll keep trying to come up with some bullshit or other to say. And the past is a fiction, anyway, that we all keep creating and re-creating, so you can never come to the end of it.

Alex: Did you have any stories thought out in your head about a card before you’ve picked it out or did they all pretty much start as an improv of sorts?

Josh: I wouldn’t say I had anything completely thought out, but, sometimes, since my mind is once again intertwined with my cards, I can be thinking of a story and see how a card or a player might fit into that story.

Alex: What, if any, baseball-card books did you read either as a kid or then later on?

Josh: I read a lot of baseball books as a kid, but no baseball-card books. Later, in my twenties, a friend clued me in to the classic baseball-card book, and one of the best baseball books of any kind, The Great American Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book, by Brendan C. Boyd and Fred C. Harris. The authors riff hilariously, nostalgically, and lyrically on the cards they collected in the 1950s and early 1960s. It’s a big inspiration for my own writing on my site and in my book, probably the biggest direct influence along with Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes.

Alex: When you read the Flipping, Trading card book, did that help cement the idea that cards were not only a worthy subject for a book but that it could be done in weird and original ways?

Josh: When I first read it I just remember laughing a lot. But certainly it helped open up some thought that the cards could be a jumping-off point for all manner of pontification and elegy and celebration.

Alex: Tell me more about Exley’s influence. Is it a matter of theme—the obsessed sports nut—or his gonzo-prose style?

Josh: In terms of influence, not really either of those things, primarily, though they’re definitely part of it, but, rather, his ability to expand the art of narration to include something that looked in some ways like my world. Other writers I loved expanded the possibilities for me in other ways, but they didn’t let me know as strongly as Exley did that it might be possible to tell a story about my own stupid life without distorting it to resemble the narrative worlds of Jack Kerouac or J.D. Salinger or Raymond Carver.

Alex: Did you know ahead of time that you wanted to revise card posts you wrote online for the book?

Josh: I knew that I wouldn’t be able to touch anything I’d already written without testing it and pounding on it and reworking it, just because I’m always revising everything. And I also knew that I had a distinctly different purpose with the book than I had with the blog. While the blog allows me to riff whichever way the wind blows, in the book I wanted to build a long narrative with at least some semblance of a propulsive momentum from start to finish. I knew that the raw material for the latter was in the blog but that I’d have to wrestle it all into a new shape.

Alex: Was it difficult for you to structure a narrative around the fragmented concept of individual-card chapters? At any point did you have to drastically cut things down because they were too tangential?

Josh: I’m tangential by nature as a writer and as a relatively adrift human being, so the cards at the head of each chapter actually helped anchor the story with a concrete reality that my aimless life lacks. But yes, I did have to make some tough final cuts of baseball cards and baseball-card tangents. Sometimes I had to make a cut to adhere to one of a couple formalistic rules I set up for the book—four packs, fifteen cards a pack, at least one card for every one of the teams that were around when I was a kid—and sometimes I had to make a cut because the riff at hand did not offer a way to circle back toward the overarching narrative of the book—my life.

Alex: Did you ever feel self-conscious about the memoir as a genre?

Josh: I don’t know if this answer relates to the question, but not too long ago I heard Natalie Goldberg, who is a great and inspiring teacher of writing through her books—so I hope this doesn’t come off too harsh—on an interview show pronouncing that word as “mem-waah,” and it really grated on me. She kept doing it again and again, “mem-waah, mem-waah,” and it reminded me of a person I was once at a writing retreat with who kept talking about her “mentor.” “You mean your teacher?” I said. “My mentor,” she said, giving each syllable of the word an overheated gravity.

Anyway, I guess I’ve got issues. But to me a teacher is a teacher, and a book is a book. I was writing a book that I wanted to be like the books I have loved the most and that have meant the most to me in my life, which were all close-, single-P.O.V. books and—except for the work of Kafka and Bruce Jay Friedman—all first-person narratives. Some of them have been classified as nonfiction and some as fiction, but the lines between the two in many cases are blurry. Basically, they are all stories of narrators hanging on for dear life.

Alex: That’s a classic. I can’t help but think of John Malkovich in Burn After Reading talking about writing a “mem-waah.” Part of me feels that there is something so self-indulgent about the genre that there is something really distasteful about it. But that’s just my own self-consciousness because I’ve read some great memoirs like Half the Way Home by Adam Hochschild or North Toward Home by Willie Morris, to name just two. And you are right, in the long run a novel can be a thinly veiled memoir just like memoirs can contain a lot of fiction.

Josh: I’ll have to check out those books you mention.

As for the thought about memoirs and novels bleeding into one another, I just want to add that all memoirs contain fiction because of their reliance on memory, which is a creative mental faculty, rather than, as it is sometimes imagined, some kind of mechanical receptacle of unchanging data.

Also, I find it interesting that in some other artistic mediums there’s not the same compulsion to designate one type of the product of the medium into fact and another type into fiction. But it seems very important in the book world these days, as evidenced by all the hysterical furor over that Oprah Book Club guy whose memoir was revealed to include some tall tales. I never read that book, but my thought on it is to imagine it as a painting or a song. If it was a painting, and it moved you, it wouldn’t make a difference what kind of a painting it was. Same with a song: Did you find your ass shaking to the beat? Did you find yourself humming the melody? Then it doesn’t matter if it was “made-up” or “true.” It is a song, and you liked it.

That said, given the popularity of memoirs these days, I just want to say that my book is a memoir and that everything in my memoir is a completely accurate reproduction of past events.

Just kidding. Such a thing is impossible, but I did try to tell the truth as I feel it and as I could best remember it, more or less.

Alex: Other than a Fan’s Notes, did you read any other memoirs that you enjoyed?

Josh: I should point out that A Fan’s Notes, a first-person account of a man with the same name as the author, was classified by its author as a novel or, more specifically, as “a fictional memoir.” He starts the book with a note to the reader that ends, “I ask to be judged as a writer of fantasy.” He’s a bullshitter! As are many of the authors who I have loved in my life and who I could feel helping me along as I tried to inch through the darkness with my book.

Another novelist and obvious favorite of mine, Jack Kerouac, imagined that when he was telling his thinly veiled fictionalized accounts of his life that he was spinning out a yarn in a barroom, and the barroom tale would certainly be a genre to allow in some bullshit. Frank Conroy and Tobias Wolff were another pair of fiction writers who wrote works that were classified as memoirs—they read as fiction, with scenes including dialogue that had—considering the frailty of memory—to have been partially invented. That had a tremendous impact on me (Stop Time and This Boy’s Life, respectively).

When I was a kid I read The Basketball Diaries by Jim Carroll because I thought it’d be about basketball, and because of the diary form and the author referring to himself as “Jim Carroll” I took every word as absolute fact. Later, I came to realize that it was indeed the truth but that he was getting at that truth not by reporting “facts” but by letting loose with a voice expansive enough to include the tall-tale yarn-spinning that has been a central vein in American literature since the time of Mark Twain. He was like The Beastie Boys in Paul’s Boutique, another influence on my book for both the way it embraced the genre of first-person bullshitting and for the way it incorporated an avalanche of pop culture references into a Whitmanesque Song of Myself.

So music was helping me along, too. I got the final push to write the last section by blasting Fun House by The Stooges. Movies, too, like Ross McElwee’s Sherman’s March, the best digression-embracing memoir you could ever hope for. And I wouldn’t be a good son of an art historian if art wasn’t helping, too: I wanted the book to have some of the mystery, or at least the sense of care and love, that Joseph Cornell gave to his boxes. I love the way he elevated being a fan—most notably of ballerinas, not ballplayers, though he does have a baseball-themed box at The Baseball Reliquary (web site)—into an art form all its own.

Alex: Funny that you mention Cornell who is one of my favorite artists. In a way, the digressions are part of what your story is all about. It’s all of a piece, the idea of a narrative told through the fragmented memories of the cards. Did you ever find you were straying too far from the narrative?

Josh: The process wasn’t so much one where I felt I was either on the right path or straying from that path but, instead, like I was trying to wrestle a big, amorphous blob to a draw. My life has been pretty aimless. So what’s the narrative? In that question is the wrestling match and the blob.

The cards helped me deal with the blob, so in a weird way the digressions about the cards were actually vital in helping me make some kind of sense of my meandering life.

Alex: Do you still find yourself attracted to stories about narrators hanging on for dear life? Is that the major theme in your life? And has it changed at all?

Josh: I do still like those kinds of stories, but it’s hard, perhaps harder than it used to be, to find those stories that speak to me as strongly as the ones that are in my personal book Hall of Fame. I think it’s a little like how I am with music—when I was younger I devoured music and was often discovering new artists that spoke directly to some fresh wound on my psyche. Now I pretty much stick to my favorites, which with a few exceptions all first got into my head over 20 years ago.

The difference between music and books is that I still read constantly and widely and curiously, whereas with music I really have stopped growing for the most part, though I still love music. I just don’t experience very often that rare and beautiful feeling that an author is speaking directly to the center of my being.

Alex: Have your tastes changed? Are there writers that you’ve outgrown in a sense of how directly they speak to you?

Josh: I have become more appreciative of writers with quieter skills, for example short story masters like Anton Chekhov and Alice Munro.These writers would not have been able to grab me when, for example, I was 17 years old and high on bong hits, but I am blown away by them now, the way they can suggest the deepest and most solid realities on the page without any self-indulgence or even any apparent effort. A contemporary of Chekhov’s once wrote to the Russian master that Chekhov’s writing made the contemporary feel like his own stories had been written not in pen but with a charred log. But my personal favorites are still my favorites. I re-read them religiously.

Alex: Were you ever concerned about how you portrayed yourself as a character? As either too self-pitying or unsympathetic? Or did you exaggerate those qualities? I remember Pat Jordan once saying that he was extra hard on himself in A False Spring because otherwise he didn’t feel he’d have any credibility being critical of anyone else.

Josh: Pat Jordan is a master at presenting himself “warts and all.” Tobias Wolfe, too. I guess I just wanted to be as honest as possible. I do have a propensity for self-pity, which probably comes through loud and clear in the book. It would have been even louder, but my heroic editor, Pete Fornatale, had a good feel for when I was dipping too deeply into that well, and with his suggestions I cut back here and there on the “woe is me” editorializing and tried to just let the reimagined moments do the talking.

Alex: My taste in writers has changed like yours too. I’m more inclined to read Flannery O’Connor now than William Faulkner. Have your tastes in other mediums—music, movies, etc.—changed in a similar vain?

Josh: Music, not so much. As I mentioned earlier, I pretty much stick to the stuff that grabbed me back when I was a young and open-hearted, drug-doing lad, or possibly I augment those preferences by delving further back in history into the influences on the artists I like.

My passion for movies peaked in my twenties, when I saw them constantly, especially movies from the 1970s, especially ones that happen to end with a bullet in the head. This is not why I was drawn to them, I don’t think, but there really were a lot of great movies from that decade that ended more or less that way: The Deer Hunter, Nashville, Serpico, Taxi Driver, Mean Streets—sort of—The Wild Bunch, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, etc.

I still love those movies, but I’m not racing out to rent them constantly and reveling in their life-affirming sacrificial splendor, or even thirsting for new movies that might hit on that same note of violent hyper-realism—or however you want to designate the brilliant era of movies in the 1970s.

But I still love movies from that decade the most, and when I find a good one that I hadn’t seen before, I’m happy. The two most recent “finds” along those lines were Two-Lane Blacktop, a Monte Hellman film from the early 1970s that starred two musicians, James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, and Over the Edge, Matt Dillon’s first movie.

Alex: Faulkner felt that The Sound and the Fury was a failure. He tried to tell it through the eyes of an idiot and having failed he wrote it through the eyes of his brother, and that was a failure for him so he wrote the two other sections. Years later when Malcolm Cowley was putting together The Portable Faulkner, Faulkner wrote an appendix. Cowley noticed factual discrepancies in what appeared in the book and the appendix and Faulkner said, “Go with the Appendix.” In other words, he was still writing the story, still trying to get it right.

I use this as an example not to compare you to Faulkner, but you mention how you’ve honed the essays from what might have been a first draft online. Do you feel like the story is complete, to your liking or, if you had to write it again now or in five years, they’d keep changing?

Josh: I don’t see the stuff that I’ve done online as a first draft, in part because I often write several drafts of a given piece before posting it, but also because it is its own thing, an open conversation with anyone who wants to join in. But just like that conversation is ongoing, my understanding of “my story” and how best to tell it will always be changing. My writing is either dead to me or a work in progress. I most recently noticed this when I got the hardcopy of my book and could not get a single flicker of feeling from it until I started preparing for a reading at a bookstore and decided to start condensing a couple of the posts. Once I started working on the book again, it opened up to me and came alive again.

But I wouldn’t rewrite this book, because it’s true for me at this time in my life. It may not be true later, but I’ll write a different book. I think writers who tamper too much with earlier stuff often risk carving the heart out of it. Example: George Lucas redid the scene in Star Wars when Han Solo offed a guy in the bar scene so that it was clear in the revision that Han Solo was not the first to draw his gun. He wanted Han Solo to be beyond the shadow of a doubt a hero, instead of the more ambiguous character in the original version of the movie. When I read about this revision it made me sad.

Alex: Over the Edge is really good. I think Dillon was fantastic in Tex, too, which to my mind is the best, most natural of the S.E. Hinton adaptations. I was so offended by the idea of Lucas reworking Star Wars. Then when I finally saw it I actually liked most of the changes, the visual stuff. But the changes in tone—like the Han Solo scene and then the addition of a scene that featured Jabba the Hutt—I thought were awful because they changed the emotional tenor of the movie.

Josh: Yup, a bad move. Why is it that decisions involving guys named Joba always invite so much controversy?

Alex: Well, at least that dildo in the movie didn’t wear those pretentious eye glasses that Chamberlain rocks, or his 37-IQ flat-brimmed lid.

Josh: Ha!

Alex: So were there any specific cards/chapters that were especially difficult to realize? Any that you felt, not precious about, but that you didn’t exactly nail?

Josh: In general, the cards in the last section were harder to pin down, in part because I had to collapse many years of my life into short spaces, and in part because I hadn’t previously paid as much attention in my writing to those years of my life as I had to my childhood years, which I’d been writing about for years and years, getting the story straight, like Mr. Orange practicing his tale in Reservoir Dogs—the last of the great movies that end with a bullet in the head?

As far as what chapters don’t feel to me as if I nailed them, that’s a very difficult question for me right now. I don’t ever really feel like I nailed anything, anyway. How can you know? I remember when I was a young writer, in college, and the poet Mark Cox came to give a reading, which was great, and then afterward stuck around to answer some questions. He was talking about his process, specifically revising, and I asked him, “How do you know when a poem’s done?” He heaved a sigh and said, “When you can’t bear to even look at it anymore.”

Anyway, right now, like I said, the book is inaccessible to me. It’s not really mine anymore. I know that certain sections came about differently, some in a rush of inspiration, others more methodically, but I don’t think the “making of” tale is ever a guide to what writing ends up connecting more strongly with a given reader. I’m sorry to be so vague about all this, but I really find that I can’t differentiate the bad from the good in the book right now.

Alex: Which ones do you feel closest to? And which ones do you think are the most successful?

Josh: I think the question of closeness, since it’s a feeling, has got to be answered subjectively. The first one that comes to mind is the Nolan Ryan chapter, the section where I describe going swimming at a nearby pond with my brother, right on the cusp of him going away to school. That one moved me as I was working on it. They all did, one way or another, but that one happened to come out in a fairly unbroken rush, so it probably impacted me more than the ones that came together more slowly. I’m not sure if it’s successful. I hope so.

Alex: The Garvey card is one of my favorite chapters in the entire book. Can you explain how this one came together?

Josh: That one is a real Frankenstein monster in the sense that it draws on stuff from a couple different Garvey posts I did on the blog as well as on various “fictional” attempts to address the “chimney in the van” element of my childhood, attempts that began maybe fifteen years ago. I was trying to cobble all these things together and in the end I think I had to just kind of write the whole thing as if from scratch with all those earlier efforts in my head. At that point, the Garvey stuff began playing more strongly off the scenes of me and my family.

Alex: What do you make of what happened to Garvey later on?

Josh: The stuff about Garvey’s money troubles that came out a few years ago, I honestly don’t recall even registering it. I’m sure I must have heard about it, and I probably shrugged. You know, new day, new tarnishing of a sports icon. Of course, Garvey had already fallen off his pedestal years earlier, at the end of his playing career, when all that stuff about his “extracurricular” activities started coming out. That was right around the time when my baseball fandom was at its lowest—after the bloom of childhood love and before the adult realization that it was like family—something in the middle of my life for good.

So I wasn’t paying much attention, and even if I had been I don’t think I would have been particularly staggered by the revelations, since I didn’t idolize him to begin with. History has been cruel to Steve Garvey, and not just via the gossip pages. Has anyone ever fallen farther under the scrutiny of the newer, more sophisticated statistics? He was a huge star in his day with his seasons of 200 hits and 100 RBI and .300 batting average, and then after he retired those statistics lost their luster as overrated “counting stats,” so much so that I think it’s possible that Steve Garvey is now a little underrated. Good glove, good power, excellent durability. You could do worse.

Alex: I know that’s like when a guy like Jered Weaver is called an innings-eater. It seems like such a putdown, but he doesn’t exactly suck.

Josh: I think games played is a huge stat. I leaned on it heavily one time to make a consciously hysterical devil’s-advocate case on my blog for Pete Rose as the best player of the 1970s. I didn’t really believe that he was, but I wanted to make the case for him so as to make the case for durability itself. On a given day, he can’t really hold a candle to Joe Morgan, but over the course of 162 games he is there every day, while Joe Morgan’s value is diminished somewhat in the same span by his being replaced in the lineup for 20 or so games by the likes of Darrel Chaney.

Alex: What did Ian and Tom and your mom and dad think of the book?

Josh: The response from the family has been great. I am lucky to have a great family. Some of the stuff was pretty painful for them to read, I think. They’ve had some preparation in the matter of seeing subjectively viewed portions of their lives put into my writing. I’ve written a lot of fiction that covered similar terrain and have explored a lot of the material on my blog, so it wasn’t as if this was their first dose of my propensity to talk about intimate family details. I think this might have helped.

Just before the book was going to come out, I was talking to my dad about how I was worried about how he might respond to the book, and he assured me that he understood it was my perspective on things, not some kind of objective “truth,” and then he gave me a very rousing speech about how I should never worry about how other people might react to my creative efforts. Everyone else in my family has always been just as supportive, all my meandering life. I didn’t show them drafts, but they read the proof copy of the book. I hope that they—and everyone—sees that they are the heroes of the book, the people who have helped me along all the way.

Alex: So do you feel like the book is now, not dead to you, but outside of you, now that it is published and out there in the world? And do you feel that the stuff you are writing on the blog was molded by the book, or how you developed as a writer with the book? Or is it more of a give-and-take experience with the readers?

Josh: The book is definitely “not mine” anymore, which feels weird, especially since it contains personal stuff that I’m not even really comfortable talking about in a regular conversation. I’m not sure how the book and my work on the book is affecting the continuing work on the blog, except to say that at first I found it hard to write anything because I felt depleted, but that eventually went away and I got back to doing it because it helps keep me out of trouble.

Alex: Loved your piece on Wrigley Field the other day. The Copa reference from Good Fellas is spot on, exactly how I felt when I was at Yankee Stadium with Ray Negron on several occasions. I don’t mean to be obvious, but are you enjoying promoting the book?

Josh: As far as the one reading, so far, and the radio interviews and the one TV spot with the Marlins guys at Wrigley, I enjoy most of the during and I enjoy the after but the before turns my stomach into knots. The guest articles and written interviews are mostly fun, too, and I’m glad to have the chance to do them, but I’ve noticed that they have been eating up a lot of my writing time.

Alex: Have you been able to soak in the critical success of the book or does it make you uneasy?

Josh: It’s been really gratifying to read good reviews, but I’m waiting for a piano to fall on my head.

Alex: Schmuck, just make sure to wear a helmet. Anything else memorable happen yet?

Josh: It’s mostly been “from the comfort of my own home” stuff, so nothing too interesting yet, besides the Wrigley Field visit you mentioned earlier. But I’m scheduled to appear at a signing in Boston with Bill Lee, so that might change.

Alex: Might want to have a chin strap on that helmet. Okay, last thing. I know it may be too early to ask, but have you considered what you’d like to do next?

Josh: I’m working on a little book for a series of books on film. My assignment: The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training. After that, I’m not sure, but I’m feeling pretty ready to leap off into some unknown.

Alex: Why the sequel? Why not the original? Because it’s already been written about? I love the choice. It’s so particular and scrubby.

Josh: It was never even a question for me between the two. I could (and will) write a whole book about why, but I guess the short answer is the sequel means more to me. Nothing against the first movie, which is great and groundbreaking and has the trump card of Walter Matthau, but the second movie—which I saw first—was everything a nine-year-old baseball nut could want in a movie. Plus, Kelly Leak goes from side story to Great American Hero in the sequel, in the process leading the Bears into the great American medium’s greatest genre: the Road Movie.