I’ve have been working on a proposal to write a biography on Curt Flood for a Young Adult audience. Needless to say, I’m pretty jacked up about it. And who better to talk about Curt Flood than Marvin Miller, now 86, the former Executive Director of the Players Association? There is an excellent chapter in Miller’s autobiography, A Whole Different Ballgame, on Flood, so I didn’t think he’d mind talking about him.

Miller was easy enough to get in touch with.

“He’s in the book, under Marvin J. Miller,” said the receptionist at the Players Association. Ten minutes later I had scheduled an interview.

Alex Belth: When did you first learn of Curt Flood’s plan to sue baseball?

Marvin Miller: My first knowledge of it was his telephone call from St. Louis, to our offices in New York. It came right after he had been notified that he had been traded. And I believe that his first notification had not come from the club, but a newspaperman, which was adding insult to injury.

[According to Flood’s biography The Way It Is, Flood didn’t hear about the trade from a reporter, but from Jim Toomey, assistant to the Cardinals GM Bing Devine: a flunky. A pencil pusher. A schlub.]

Flood came to New York. But he did something first. He had a personal attorney in St. Louis for business matters. He had a portrait business; he was an accomplished artist. And for whatever reason, he had a personal attorney. He asked in the telephone call if he could bring him and I said sure. So that first meeting involved Flood, his attorney [Allan H. Zerman], Richard Moss, the general counsel of the Players Association, and myself. We met for hours. For hours and hours. It started out in the office, it continued as lunch in the hotel restaurant for pretty much the rest of the afternoon.

Alex: Were you excited about a player of Flood’s stature taking on the owners? And did you think he had any chance of winning?

Marvin: Yeah, I think I was excited about the idea that somebody thought so seriously about the problem. But to answer your next question, no, I didn’t think he had a chance. I spent a good part of that day—and subsequent days and subsequent phone conversations—and explained to Curt Flood and his attorney why I thought the case could not be won. I thought it important to do that because he was risking a lot with this. I knew that it was almost certain that if a suit were filed that he would not be able to continue playing. I knew that he was no longer a 20-year-old kid, but somebody who was going to be 31 or 32 at that point.

And that taking time off from playing while a case would wind its way through the courts meant almost certainly that he would not be able to regain his old form and play again. Much more than that, I thought that it was important for him to know all of the risks he was taking. Ending his career as a player was only one of them. I told him that I did not know what his ambitions after his player career were, whether it included being a manager or a scout. In other words, to stay in Major League Baseball.

I said, “If your ambition is running in that direction you have to know that the owners are very vindictive people. And they have long memories. They are not going to take kindly to a lawsuit, and I would be amazed if you were not blackballed from everything. That is part of what you have to understand.”

I also explained to him that I didn’t want to know anything but what I was about to say, but I wanted him to think about it. I said, “If there is anything in your life that you would rather not see on the front page of your local newspaper, then you shouldn’t go ahead with this.” Because I would not put it past Major League Baseball to root out anything unpleasant in his life and release it. Even though I had asked him not to tell me about anything in his life, he told me anyway. He said, “Well, I do have a brother that is in jail for drug passage.”

I said, “Well, there is something that is not publicly known and if you’d rather not have it publicly known then it’s something you have to consider, because it will become publicly known. So, Flood takes all of this in. A lot of what I’ve just mentioned did not happen in our first conversation, but before the case was filed, in subsequent conversations, and so on. I felt it my responsibility to play devil’s advocate and then some, so Curt would understand all of the down side to this.

At one point I finally said, “You know winning the case would be a million-to-one shot. The Supreme Court has already ruled on this two times, and the court just doesn’t reverse itself that often.” Major League Baseball has always gotten the silk-glove treatment by the court, by the Congress, by presidents. Baseball is considered holy writ. And the courts look away way all the time with regard to baseball.

Alex: Why is that?

Marvin: Well, because it’s holy writ. I mean, you don’t need any better example than the first Supreme Court case in 1922, Federal League v. Baseball. Oliver Wendell Holmes, a noted jurist, and a poet, wrote the most asinine decision you ever saw in a case that said that baseball was not covered by the antitrust laws. Not because of anything it said in the law but because baseball was not an industry operating under interstate commerce. This, about an industry that in the Major Leagues alone, involve travel across state lines from New York to Pennsylvania to Ohio to Massachusetts. Holmes, to his ever-lasting disgrace, wrote that baseball is an industry, that’s not an interstate commerce, and it’s not even an industry. It’s a series of exhibitions he said. [Heh-heh] Exhibitions with millions of dollars changing hands. Such nonsense.

If you ask me how a noted and able jurist ever gets himself to write an opinion like that for a unanimous court, [heh-heh], I just can’t explain it. Numerous court decisions after that, both on the Reserve Clause and all kinds of things effecting baseball, they never rule against baseball. At least in those days.

Alex: Considering the long odds of the case, what did you hope to gain from the suit?

Marvin: Well, it wasn’t so much what I hoped to gain. Before our meetings were over I was convinced that Curt Flood was going ahead with this. Therefore, since I couldn’t stop it, my concern was to have the best foot forward, to get the best possible council for him, to prepare the best possible case, so that it would not result in causing further damage for court cases in the future. It was not a question of hoping to gain; it was a question of hoping to cut losses.

Alex: Were you surprised that Flood v. Kuhn made it all the way to the Supreme Court?

Marvin: “Surprised” is a funny word. I did not know. As you probably know, it takes four Supreme Court justices to agree to hear a case. I had had some discussions about this with lawyers whom I respected. And there were differing opinions. I just did not know whether the court would accept it for argument. It was great when they did because it meant that at least four justices felt that there was some merit and it was worth the time of the Supreme Court to look into it.

Alex: Even though the Flood case ended in failure, how much of an influence did it have on the advent of free agency a few years later?

Marvin: That is very hard to assess. I’ve thought about it a lot, and I’ve always felt that it must have had some effect. If it did nothing else, it brought to the center of discussion the inequity of the Reserve Clause. The Reserve Clause had existed for a hundred years up to that point, but there was almost no discussion of it before the Flood case.

Writers who cover baseball never wrote about it. Almost nobody did. Here and there, there were people in academia who did write about it. Once in a while it would get mentioned at a seminar in a college group. But by and large, there was no publicity about it. I think what the Flood case did was to bring it front and center. It focused attention. I think it made a few people realize for the first time how bad that system was, how un-American, if you will. To that extent Flood’s case made a positive contribution. I think it brought out to the players who also were in the category of not having really focused on it, because of something they had grown up with and had been told repeatedly that baseball would collapse without it, and all that nonsense.

It focused the attention of the players not just on the case itself but the arguments being made. In that sense it was an educational contribution. I think it educated the media, it educated the players, it educated the general public to a certain extent, it educated a few congress people here and there, it caught the attention of at least four justices of the Supreme Court, and it may have even reached some of the owners.

Alex: It’s ironic that none of Flood’s peers managed to show up at his trial. Was that a bitter disappointment for either you or Flood?

Marvin: I think for Flood it was a bitter disappointment. I think for me it was a disappointment about myself. I had not made a concerted effort to get players to come. One of the reasons is that I was always cautious about exposing players to danger to their careers. I felt at that point and time that individual players coming to court, where there were owners and the commissioner and owner’s attorney’s also attending. I felt that kind of exposure was more dangerous than I wanted to recommend.

Now you have to understand that we are still the early days of the union, we had not been tested by a strike yet. Our first strike was in ’72. We still did not have the right to have grievances eventually heard by an impartial arbitrator.

Alex: When did that change?

Marvin: In the 1970 basic agreement. But when Flood was traded and he made his mind up to sue baseball, it hadn’t been agreed to yet. Up till that point, if players were discharged, or discriminated against, you could grieve but it would eventually be heard by the commissioner of baseball who was an employee of the owners, who was paid by the owners.

Alex: So the provision in the 1970 basic agreement that arranged for an impartial arbitrator was far more important to how free agency came about than Flood’s case.

Marvin: Oh, without any question. Because as you know, what eventually overturned the Reserve Clause was a grievance heard by an impartial arbitrator in 1975, and without that having been gained in the contract, it would have been heard by the owner’s commissioner, who could tell you up till today, how he would have ruled.

Alex: How did the owners overlook the provision?

Marvin: Like so many things, there is a mythology in baseball. One mythology is that baseball labor’s relations are the rockiest ever seen in any industry: strikes and lockouts every time a contract comes up. All of it untrue. All of it totally untrue. All of the important progress made in labor relations in baseball, all of it, from the first collective-bargaining agreement, to the recognition of the union as the sole collective-bargaining representative, to a grievance procedure with impartial arbitration, from salary arbitration to the free-agency agreement: all were resolved without strikes. All of them. It’s amazing to me how revisionists can rule history.

It’s not just like this in baseball; it’s like this in a lot of things. But in baseball since I have firsthand knowledge of it.

[Laughs]

At any rate, the negotiation of the impartial arbitrator as the final point in the grievance procedure in the 1970 agreement was achieved through collective bargaining. Through discussion, through proposals, and counterproposals, through argument.

Alex: Did you have any idea how important this ruling would eventually be for the players in the future?

Marvin: I had a vision of how important it would be before I had it.

[Laughs]

I think it was a victory for baseball. I know the owners would not agree with this. Anytime you enhance justice and human dignity, it’s an advantage for everybody concerned. I think the notion that a commissioner in baseball, who is recruited by the owners, whose powers are only what the owners will give him, who is paid only by the owners, who can be fired, and is fired at will by the owners, can not be an impartial individual whether it’s over a tiny grievance or a big grievance between the employees and the employer that pays them. It can’t be. It’s a conflict of interest that sticks out all over the place. Any time you get rid of a conflict of interest that it so glaring, you have done something that has enormous benefit to everybody involved.

Alex: Flood’s legacy is often misconstrued. I often hear him referred to as the first free agent, or the guy who started free agency, which isn’t the case at all.

Marvin: You are right; it wasn’t the case at all. The case lost, beyond appeals. Nothing concrete came of it other than the educational aspect that we talked about before. The union itself, which through the unity of its members, through the understanding of the members of what needed to be done, through the skills of people like Richard Moss, who was the general council, who argued the case, to the union’s successful effort to have both a grievance procedure and eventually impartial arbitration, all these factors and more, were responsible for the progress that was made.

Alex: Why would Curt Flood’s story be meaningful for a high school kid growing up today?

Marvin: [Laughs] It’s hard to put myself in the place of a young boy today. It’s been a long time since I was a young boy. But I think Flood’s life as an adult was admirable. People often talk about role models, about professional athletes as role models. I don’t necessarily accept that athletes are or should be role models. But when you find somebody like Flood who was not just a superb performer and great teammate—as all of his teammates from the St. Louis Cardinals will tell you—but as someone who thought about social problems and about injustice and who was willing to sacrifice a great deal to try and change things. I think the integrity of a man like that is so impressive that it’s hard to describe.

Alex: It puts Flood in Jackie Robinson’s company in terms of having a ton of guts.

Marvin: I will not run down Jackie Robinson’s contribution in any way—Robinson had to have great internal fortitude, great courage, great discretion, judgment, all of those things. Curt Flood, too. But Flood was risking something. Risking a great deal. Robinson was being given an opportunity and he did well. Earned it and then some. Flood already had it. And was a star player, making close to a top salary in the Major Leagues at the time. He clearly knew the risks—I learned this first hand—and took them anyway.

I think you have to recognize that while the Robinson experience did eventually pave the way for black and Latin players to play in the Major Leagues, the terms under which they worked were not that great. In fact, they stunk. Truth be told, they were still the most exploited people in the country. And by that I mean, not that they were the poorest in the country. As an economist, I will tell you that exploitation means the difference between what your services are worth and what you get paid. With that definition, Major League Baseball players, including those who benefited from Jackie Robinson’s experience, were the most exploited people in the country. While Flood alone did not change that, he helped. The union changed all that, but Flood’s contribution was significant.

Alex: Did you keep in touch with Flood when he left baseball? Did you ever run into him again?

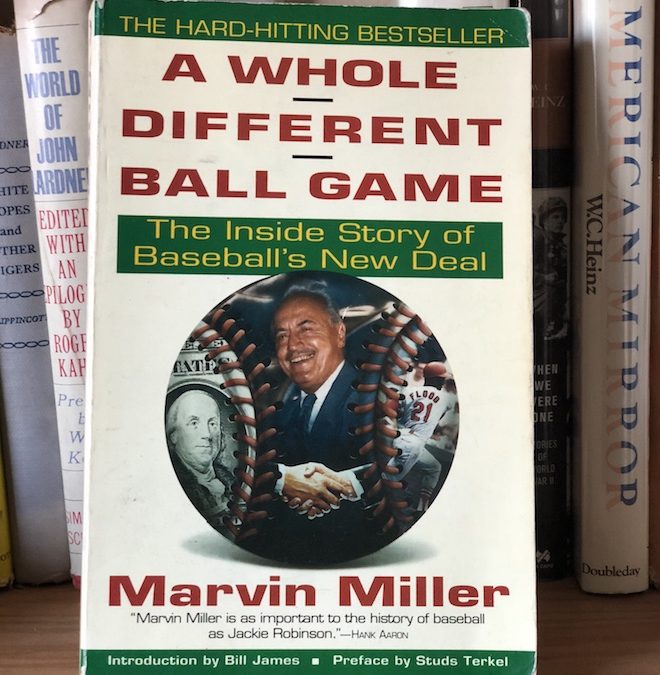

Marvin: Well, not exactly run into him, but I wrote a book that was published in 1991 called A Whole Different Ballgame. The publisher, in conjunction with the publication of the book, hosted a book party in New York here. I invited Curt Flood and Mrs. [Judy Pace] Flood. They came to New York. We had several meals together and we talked about old times together, and they attended the party and I was very glad to see them.

Alex: There is a general impression that Flood that ended up a sour, resentful man. The martyr. Was he able to move on with his life outside of baseball and get come to peace with his suit against MLB?

Marvin: That’s, that’s my impression of him. I don’t know if you know this or not, but before he became ill, sometime in the mid ’90s, Don Fehr—the present director of the Players Association—invited Curt to attend a board meeting. I’ve forgotten where it was held, I wasn’t there, but all the reports agree that when Curt Flood walked into that room the board meeting was in progress, and the board meeting stopped, and there was a long, loud standing ovation.