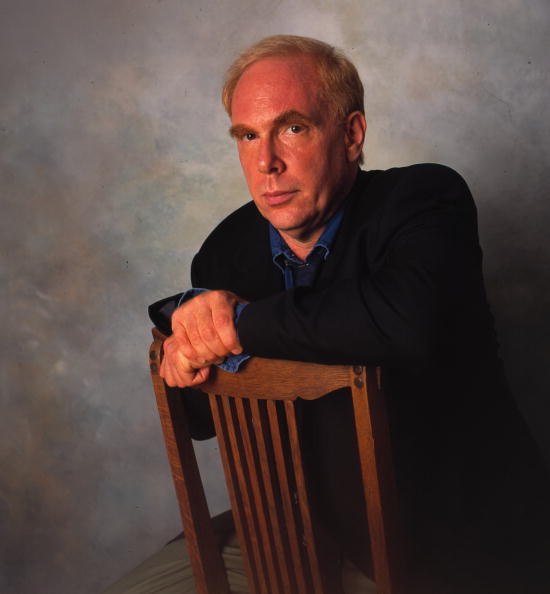

The Classic Q&A: Ron Rosenbaum

Though he needs no introduction, we’ll give is a shot: Ron Rosenbaum is the author of seven books, including three anthologies of his magazine work (most recently The Secret Parts of Fortune). He began his career at The Village Voice, and developed his style as a practitioner of longform, investigative journalism for Esquire during the Harold Hayes era. Rosenbaum went on to write or Harper’s, The New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, New York Magazine and Punk. After which he turned mainly to books, including, Explaining Hitler, The Shakespeare Wars, and How the End Begins. He’s taught writing seminars at Columbia J-school, NYU and the University of Chicago. He is one of the finest magazine writers of our time and he joined us in conversation recently to talk about his career.

Alex Belth: You got into the business in your early twenties but you didn’t study journalism in school. What led you to the field?

Ron Rosenbaum: As an undergraduate English Lit student at Yale, I studied Close Reading, where the idea was if you spent enough time with a text you would find the attentiveness paid off. I later found that in reporting you could apply the same kind of close reading attention to court documents, to transcripts of interviews, and come up with stuff that wasn’t necessarily apparent immediately.

I was very fortunate to get a break early. I had a year’s fellowship at Yale’s graduate school in English Literature. I still loved English literature but I could not bear the idea of the academic life. One late night I was thumbing through the classified section of The [Village] Voice, thinking I might get a traveling salesman job, something like that — and found a small ad for The Fire Island News. They were looking for an assistant editor. I got the job and the editor quit after two or three issues so I became editor of the paper basically. It was a summer paper but a few people from The Voice, notably Nat Hentoff, and the editor Dan Wolf, had homes out in Fire Island and were reading my stuff.

At the end of the summer I went in for an interview and to my surprise got hired on the spot because they had a slot for counterculture reporting. I don’t know if the name Don McNeill means anything to you but he was the early era of counterculture reporting. He was very talented, famous for having his bloody visage blown up on the front page of The Voice. Anyway, McNeill was involved with a bunch of people in a commune in Massachusetts and that summer he walked into a pond and didn’t come out. And there’s still controversy whether it was a suicide or an accident. There was a replacement for him that didn’t work out so there was an opening.

I was thrown into the Revolution, the counterculture, covering anti-war demonstrations, interviewing community leaders. I covered John Lindsay’s Mayoral election. I got to cover everything, not just “Counterculture” but my own brand of wandering America and finding eccentric or esoteric mysteries. I was also the Voice White House correspondent for Watergate. I was in the East Room of the White House when Nixon said farewell.

AB: Were you only writing features?

RR: Yes. I would spend months on pieces sometimes. It was pretty great in terms of freedom. No stupid “pegs” that have made journalism a subsidiary of public relations. I also developed a sub-specialty on New York characters, a little bit like the ones you’d find in A.J. Liebling or Joseph Mitchell’s work.

AB: You go from this academic background to being out there interviewing people. Did you enjoy that part of it?

RR: I’ve always been a shy person. My big discovery, I realized very early on—note-taking is flawed. Note-taking never captures how a person says something, the subtlety and nuance of their tonal inflections, verbal ticks that were giveaways. I’ve often paid for transcription but if I can I love to transcribe myself because you hear things and pick up things that are easy to miss.

AB: Was there an editor who help you give a sense of how a magazine feature should be shaped?

RR: The Voice did not consider itself a conventional magazine. It took me awhile to realize that it was named The Voice for a reason. They wanted voices. At the time, good magazine stories were still believed to be written in the third person based on the false belief they were more objective. Of course some conventional stories require third person, but in the really interesting stories — the ones I got do to at The Voice and Esquire — were about subjectivity, subjectivities. Dan Wolf, who was the founder of The Voice, was very encouraging. Ross Wetzsteon was not only a good writer but a very good editor. There were a lot of good people there. And at Esquire Harold Hayes, an idiosyncratic genius.

I had many, many good editors. The one thing that all great editors have in common is that they are what I call “charismatic listeners.” With Dan, I would go out, interview all these people, have strange adventures, come back with all this information spinning through my head and sit down with him and start to talk it out. And with a good editor you find yourself shaping it as you talk and they will ask a couple of questions that open new things. Some are good at line editing too, but there’s this other, less visible talent. Dan would just nod but you could tell you had his attention, his respect, his interest, and that liberated some kind of area in the cortex, the storytelling area in me that really made a big difference.

Harold had a different kind of attitude, he had a top sergeant-like charisma. I didn’t feel like I was in his league to kid around with him but if he got behind your story he’d let you know and his confidence was a huge benefit. His analysis of a story was so deep and on the mark. I was once struggling with a story about this homicide reporter for the Daily News who’d covered some 10,000 murders, he claimed. I was trying to figure out what it all meant. Harold, out of the blue, said, “Read John Milton. Paradise Lost is about justifying the ways of God to man—that’s what this guy is about. That’s the burden of his quest. Is there a reason this one dies and this one doesn’t?”

I spent two years doing a piece on nuclear war for Lewis Lapham at Harper’s, which was great. He’s a great editor in terms of encouragement. Every six months or so I’d come in and say, “Here’s where I am, here’s what I think the big questions are.” And he’d say, “Keep going, keep going.” And I did. And I think that piece is one of the ones I’m most proud of.

AB: Had you been aware of Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and the other New Journalists when you were at school?

RR: I loved the first time I read Talese’s mafia kidnapping story. Oh my God. It was so good. It was really incredible. He’s just a master at narrative seductiveness and I certainly envied that. Can’t say I ever equaled it. I read everything of his. And I loved the way Mailer could mix metaphysical digressions into his observational reporting. And Breslin’s curt eloquence. Nora Ephron! Working with her was always learning something. But I was not aware when Esquire called me up in 1970 that they were in the middle of being this sort of superchic, hip, distinguished literary journalism. When I went out to report, people in the middle of the country still remembered it for girlie pictures.

here were really two worlds. There was the downtown world of The Voice, and the midtown world of Esquire. They were both very welcoming to me.

Esquire approached me in 1970 to do this Tommy the Traveler story, which metaphorically called into question who is a Revolutionary when you have FBI agents faking that they are undercover revolutionaries, encouraging students to plant bombs. That was also a great thing about Esquire was they weren’t addicted to access. You could do a write-around like Talese did with “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold.” The fact that really smart people were reading it makes a big difference. Editors, copy-editors, fact-checkers. The one thing that The Voice had in common with Esquire was neither place was a slave to “the peg.” It didn’t have to be a peg on an upcoming movie star. They weren’t after mere celebrities, they would write about people who were celebrated for their talent. There’s a difference that’s mainly been lost. Anyway, after my phone phreaks story Harold Hayes asked me to be a contributing editor.

AB: “Secrets of the Little Blue Box,” the phone phreaks story, along with your 1977 expose of Skull and Bones, stands as your most famous Esquire piece. Did it have an immediate impact?

RR: Well, it depends on what you mean. It was hard for stuff to go viral. But it changed America in the sense of unleashing hackers and creating/reflecting the hacker mentality. And although I didn’t know it at the time—it’s been written about by Walter Isaacson—it soon got picked up by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak and helped forge what became the Apple partnership. So it had a long lasting effect.

AB: What I find fascinating about the hackers in the story is that they were enamored with the system.

RR: Exactly. A lot of them wanted to demonstrate how good they were at hacking the system so that they could be hired by Ma Bell.

AB: How did the Angela Davis story come about?

RR: Angela Davis was Harold’s idea. I’d gotten to know a lot of people in the Bay Area radical culture. I rented a house out there and followed the trails of the Soledad brothers who took the rap for George Jackson and got into the intrigues surround the subsequent Angela Davis case. At one point I designed an elaborate diagrammed chronology of the case on poster board for Esquire and sent it back to New York and Harold loved the intricacy of what seemed like a simple story. That one was a little scary in the reporting. There was a moment I was in a room with someone with a gun and I wasn’t really happy about that. But weirdly, they trusted me. My ace in the hole is my nerdiness. I’m always taking down notes. I’m always able to ask the lawyers obscure but important questions.

I think a lot of reporting is about intense preparation so you know what you’re looking for. I read everything about a subject. Make questions. Make notes on those questions. Then I’d make notes on the notes. Then I run through all of those and start to make an order. That was an important thing to learn—the more preparation you do the more a subject will respect you. But also, the more you’ll think about what the real story is.

AB: Richard Ben Cramer used to play the absent-minded mess and get people to feel sorry for him.

RR: The feeling sorry for you thing is really powerful. Also, one of the great secrets of journalism is something that Helen Gurley Brown said. If you are talking to a subject and you feel that they haven’t told you everything you don’t say, “Oh, please tell me more.” Just look at them silently. And the need to fill silence is so bizarrely powerful that they will tell you what they normally wouldn’t have confided.

AB: Was that something that came easy to you because of your natural shyness?

RR: No, I never found that easy. Often, when I later listened to the tapes of the interview I would hear that I would rush in to break the silence. The worst is when you ask a question and don’t let them answer by saying, “Of course, it’s probably because of blah, blah, blah.” And you go on and on and then they say, “Yes.” So you don’t get a quote from them.

AB: I think my favorite story you wrote for Esquire is the profile of Wayne Newton, which isn’t just a colossal Wayne Newton story but a colossal Vegas story.

RR: It’s a colossal American story. I really learned something from that. When I told people I’d spent two weeks in Vegas attending two shows a night to see Wayne Newton they could hardly believe it. But gradually I learned there was so much genuine feeling there. No matter how fake Wayne might seem he’s able to evoke this genuine feeling, twice a night, week after week.

AB: What makes the ideal magazine story?

RR: Many things. But one thing is that it calls attention to the reader to something that they never would have imagined being interested in. And you leave them with a sense of wonder. I have to think more about this.

AB: In addition to your longer features, you also wrote some lighter things for Esquire in the ’70s like the crunch of a Pringles potato chip, or the people who make the official time or the meditation on Oreo cookies.

RR: I remember when I was working on the Oreo cookie one I was at a party with my girlfriend who thought I was wasting my talent on such stories so I went over and grabbed Nora Ephron and said, “Nora, tell her why writing about Oreo cookies is a worthwhile thing.” And I forget what she said exactly but she convinced me. Nora was so smart, so wise. I haven’t met a lot of people in my life where I can say, “This person is wise.” She could also be mean. So you could be nervous about what you said in front of her. But you would always get wisdom, even if it was painful.

AB: How did you eventually come to writing books?

RR: I had an idea for a novel in the early ’80s and I spent a lot of time researching it. And I discovered two things. I don’t have the gift for fiction. All of the characters sounded like me. It was a novel that dealt with the evolution of evil. I had a contract for that, I wrote a bunch, I didn’t like it. Got out of that contract. Later, I got a contract at Random House and found out a way to write about explaining Hitler. So it became a nonfiction book about the industry of people obsessed with explaining Hitler, the theories, the controversies, the scholarship. I found I was really at home doing a huge deep dive. I found a way of doing it by focusing of certain discrete controversies and issues. It’s hard to say how much time I spent writing it because a lot of the research I did was for that novel, although the book Explaining Hitler wasn’t published until 1998. It made me realize I could write a book and I wrote two more—one on Shakespeare, another on nuclear war.

AB: Had you been curious about writing books earlier?

RR: I always thought that I could write a novel. In my case, it was misguided. I do believe that the best nonfiction is not “literary journalism,” a misleading term, but rather journalism that asks the questions that serious literature asks. It’s storytelling that happens to be true. So I don’t think it was a missed opportunity. After awhile you learn what you’re really good at. Life is short, so spend time doing that.

Read Rosenbaum’s essential work for Esquire, here.

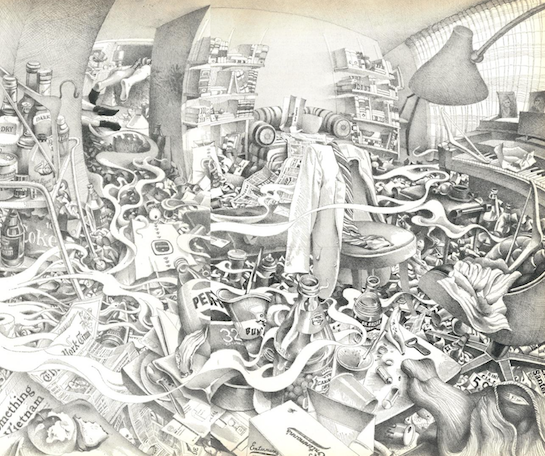

[Illustration Credit: Charles Santore, Esquire; Photo Credit: James Keyser/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images]