One of the first stories I heard about Danny Casolaro’s funeral was the five blondes at the grave site. Five stunners ranging in age from twenty to forty, all dressed in black, all weeping copiously.

I was feeling pretty bad about Danny myself, for my own reasons. I’d been thinking, Maybe I shouldn’t have yelled at him the last time we spoke. Maybe I shouldn’t have been so harsh, shouldn’t have told him, “Danny, you’ve got to get ruthless with yourself.”

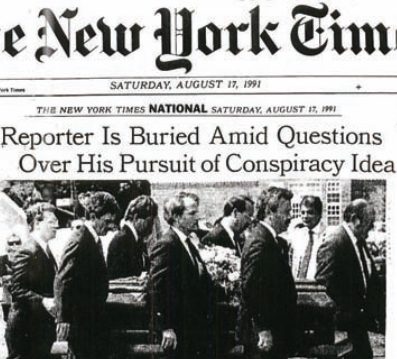

I’d been feeling that way ever since the morning of August 13, when I was idly flipping through The Washington Post and froze at the headline: “WRITER PROBING INSLAW CASE FOUND DEAD— Freelancer Was in West Virginia to Meet Source, Friends Say.”

Friends were saying more than that. Friends and family were disputing the local coroner’s hasty preliminary verdict of suicide, a verdict issued before the locals learned about who Danny was and what kind of story he’d been looking into. About the death threats and warnings he’d been getting in the final weeks before he was found, his wrists sliced open with an X-Acto-type blade in a bloody motel room bathtub. The friends were saying that Danny was hot on the trail of the long-sought Missing Link between the scandals that had been convulsing Washington—B.C.C.I., the October Surprise, and Iran-contra—and that he was killed to keep him quiet.

And it wasn’t just friends saying this: a former U.S. attorney general, Elliot Richardson, the ordinarily circumspect Brahmin, was calling for a federal investigation, and suggesting Danny “was deliberately murdered because he was so close to uncovering sinister elements in what he called ‘The Octopus.’” Was this another Silkwood case? Was Danny murdered because he was “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” as Time put it?

But at that point I wasn’t thinking murder. I was thinking guilt—my own. I’d had several phone conversations with Danny about his Octopus idea in the weeks before he died, and I’d been pretty skeptical: a lot of it sounded like a rehash of familiar conspiracy-theory connections. That’s what I’d meant when I raised my voice and enjoined him to be “ruthless” with himself: slash away the underbrush, so that whatever he had that was news would emerge. Still, when someone you’ve yelled at to be ruthless with himself is found dead with his wrists slashed, it makes you wonder if he took your words too much to heart.

Which is why I had to go down to West Virginia. Which is why I’m sitting fully clothed in an empty bathtub in the motel room just across the hall from the one in which Danny died, here at the Sheraton Martinsburg (“where meetings and fitness are our business”). Staring up at the cheap cottage-cheese-textured ceiling of the bathroom, perhaps the last sight Danny Casolaro saw.

I’ve spent the past ten days immersing myself in Danny’s world, retracing his steps from the fragments and pieces of the puzzle he left behind in his notes, trying to reconstruct the vision of the Octopus that led him to meet his death here. To see if I could find out, to my own satisfaction, the answer to the murder-or suicide question: Did Danny Casolaro die because he was, in some sense, too ruthless with himself? Or because someone got too ruthless with him?

“Danny, this story isn’t fun, it’s no adventure. It’s traumatic, it’s a disease, it’s like going into the depths of insanity …. It [the story] is the Octopus.’’

—Danny’s friend Ann Klenk, summer 1991.

I didn’t know the guy well. Met him about a dozen years ago down in D.C. I was doing a story about revisionist Watergate theories for The New Republic and someone had referred me to Danny as a guy who was pursuing the “Democratic trap” theory—the idea that shadowy figures in the intelligence community hostile to Richard Nixon actually set up the Nixon White House for the Watergate bust.

What I remember most about that evening was not so much the mysteries of Watergate as the mystery of Danny.

The Arabian horses, for instance. Not many investigative reporters I knew raised thoroughbred Arabians in the heart of Virginia horse country. Danny did. Good-looking, good-natured, golden-haired Danny looked less the ink-stained wretch most investigative reporters are than a Fitzgerald golden boy. I was left with a hazy impression of a Gatsbyesque horsey-set dabbler in the arcana of right-wing conspiracy theories.

In fact, it turns out Danny did have a kind of Gatsby fixation, one that apparently persisted until the final hours of his life. One of the last people to report seeing him alive was a waitress at a Pizza Hut, the one that shares a parking lot with the Sheraton Martinsburg. She describes Danny as flirting with her in a lighthearted way on the Thursday afternoon before his body was found. She says that Danny, apparently in high spirits, was quoting to her some lines from a favorite poem, the one about the “gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover” that Fitzgerald used as the epigraph to The Great Gatsby.

According to Wendy Weaver, an attractive blonde ad exec who was Danny’s steadiest girlfriend, Danny was a romantic who loved to quote those particular lines, because it was how he saw himself. Once, Wendy told me, “he painted a tin hat gold, and came into a restaurant that I was in, wearing a tuxedo and carrying roses.”

Had Danny struck gold in his Octopus investigation or was he just gilding tin? What was the grail he died trying to find?

He started calling me last winter—I hadn’t heard from him in years—first to ask for a copy of a story I’d done for V.F. involving “the Blond Ghost,” the legendary ex-C. I. A. -covert-operations mastermind Ted Shackley (“The General and ‘the Blond Ghost,’” January 1990). He was pursuing some leads concerning Shackley, he said. Danny wouldn’t tell me anything more at that point than that he was working on “something really big,” that there was a Shackley angle to it, and that he was reluctant to elaborate (“It would take hours”).

Then, this past summer, two months before he died, he started calling me again, asking me for advice on a proposal for a book, a book he wanted to call The Octopus, about a shadowy group of rogue intelligence operatives who, in a Ghostly way, were linked to spectacular covert-world-generated scandals from the Bay of Pigs and Watergate to Iran-contra, B.C.C.I., and the October Surprise.

I liked the guy, but when I tried to cut through the thicket of conspiracy-theory connections he was reeling off for me, I just couldn’t get a clue to what he might have that was new.

And there was something in Danny’s tone of voice that disturbed me, something I’d heard before: that note of smug, condescending certainty that begins to creep into the voice of those who feel they have it All Figured Out and are quite beyond the need to document and substantiate. (Later he left a message on my answering machine thanking me specifically for the advice to be ruthless—it was the last I heard from him.)

And so as I headed down to Washington and West Virginia to begin retracing the last journey Danny took, I was so skeptical about the Octopus murder theory that I even harbored a suspicion that Danny might have staged his own death. That, while his friends were saying it was murder disguised to look like suicide, maybe it was really a suicide staged to provoke suspicion of murder. That by killing himself and leaving enough ambiguities to raise the possibility of murder Danny would make his own death the sensational final chapter of the book he never wrote—the one thing that would validate the seriousness of the quest he was on. It would be the Gatsbyesque thing to do.

But now I think I may have wronged him in at least one respect. By the time I got to the motel here in Martinsburg— after spending hours immersed in his notes, days talking with his friends, nights having strange conversations with his sources—I still didn’t believe in the Ludlumesque Octopus conspiracy Danny hyped up for his book proposal. But I now believed that he was onto something, that his investigations were real, and that, in the months before his death, they were taking him into areas that involved dangerous knowledge and dangerous characters—one of whom had already been convicted of “solicitation of murder.”

“Will you kiss me when I’m dead?”

—Danny Casolaro to Ann Klenk three weeks before he died.

The line that best characterizes the kind of journey Danny Casolaro was on in the months before his death was one I found on a scrap of paper amid the literally thousands of sheets and scraps of notebook paper, envelopes, and cocktail napkins I’d been studying. (Was the “Denise” whose number is written on a cocktail napkin from a bar in Tacoma, Washington, a key source or a waitress he was trying to pick up?)

Five big file boxes of Danny’s Octopus-investigation notes were retrieved from his basement office by his close friend Ann Klenk, who raced over there as soon as she got the news he was dead.

“He’d told me several times that summer that if I heard he met with an accident, make sure I got that shit out of there,” says Klenk, an attractive ex-girlfriend who stayed close to him for twelve years after they broke up. Over dinner at a place near her CNBC office, where she works as a producer for Jack Anderson, she told me that, toward the end, a change had come over Danny. That his obsession with the story had become grim and all-consuming and that one evening at her place he’d turned to her and asked, “Will you kiss me when I’m dead?” (Danny’s brother Dr. Anthony Casolaro reports that in the last couple of months Danny warned him “not to believe it” if he died in what was reported to be an “accident.”)

Was this another Silkwood case? Was Danny murdered because he was “The Man Who Knew Too Much”?

Anyway, there it was on a scrap of notepaper in Danny’s files, that line, written in his cheap ballpoint, probably the best testimony to how he had come to see his quest:

In the middle of the journey of our life, I found myself in a dark wood, having lost the straight path.

It is, of course, the opening passage of the Inferno, the description of Dante’s state of mind when he came upon the hole in the world that led down to the gates of hell.

Danny Casolaro’s dark wood was a bizarre, tangled lawsuit involving a computer-software company called INSLAW; unfortunately, his guide was not exactly the wise Virgil figure who took Dante in hand. Danny’s guide—some would say his Svengali—was a Machiavellian rogue scientist who wove the web Danny was tracing from a jail cell in Tacoma. And the hole in the world Danny fell into was a sunbaked Indian reservation located, appropriately enough, a few hours south of Death Valley as the buzzard flies.

Before plunging into that dark wood, it might be useful now to fill in the picture of the pre-Octopus Danny. He was always a restless soul. The son of a successful obstetrician, he grew up to be an affable, athletic six-footer, a boxer with a touch of the poet, searching for something more than his suburban-Virginia setting offered. At age sixteen, his brother Tony remembers, “Danny got it in his head to go down to Peru to look for the lost Inca treasure.” Tony recalls he got only “as far as Ecuador, where he ran into some rich guy” who distracted him into a scheme to ship corbina fish to the U.S.

Danny’s first brush with a mysterious death came when his younger sister died in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury in the late ’60s. It was never certain whether it was an accidental death or suicide. But friends say the traumatic effect of the death on his family made Danny, a Catholic, even more adamantly anti-suicide.

After graduating from Providence College in 1968, Danny began a writing career that shifted fitfully back and forth between fiction and nonfiction. In a ten-year-old resume I dug out of the file boxes retrieved from his house, Danny informs us that, “in 1969, I wrote two books and authored the initial treatment for Rain for a Dusty Summer, a film starring Ernest Borgnine.

“From 1970 to the present [circa 1982], I’ve been a Washington correspondent, contributor, columnist, editor for national magazines, daily newspapers, weekly newspapers, professional journals and trade journals including World News, National Star, London Sun, Sydney Daily Mirror, National Enquirer … El Dorado News Times, Home and Auto, Washington Star, American Paint Journal … Media Horizons magazines … Washington Crime News.”

A mixed bag, perhaps skewed a bit toward the supermarket tabs, but Danny goes on to claim, “During these years my investigative work included reporting on some of the most important stories of the decade. In 1970-71 I was one of the first journalists to expose the renewed Soviet Naval presence in Cuba, prompting the U.S. Government official warning statements …. In 1971 I was one of the first U.S. journalists to uncover the make up and composition of the Castro intelligence network in the U.S. …. In 1972-3 I was the first journalist to expose how the Chinese Communists were smuggling opium into America. In 1973 to 1974 I was the first journalist to expose and document the ‘prior knowledge of Watergate’ story, a major breakthrough showing an untold side of the Watergate Scandal.”

In fact, there’s some doubt about where his investigative output on some of these stories appeared. Reed Irvine, the chairman of the right-wing watchdog group Accuracy in Media, recalls that Danny came to talk to him about his revisionist Watergate theory. “But he never wrote anything for us and I never saw anything on the subject he ever wrote,” Irvine told me. “I think he was one of those guys who liked to talk big but never delivered.”

What’s interesting about Danny’s investigations is that they all had a definite right-wing agenda. Subversive Castro spy networks, sinister opium-peddling Red Chinese, Soviet naval nukes in Cuba—these suggest Danny had a pipeline into right-wing intelligence networks, or at least hard-right propagandists. It’s ironic that Danny’s Octopus conspiracy theory has been picked up by the left-leaning Christie Institute. Because a close reading of his book proposals makes it clear that Danny viewed the Octopus as something that subverted the right-thinking, anti-Communist covert operations he believed in, like the Bay of Pigs.

By the end of the ’70s, Danny’s life changed in a couple of important ways. His ten-year marriage to his wife, Terrill, a former Miss Virginia, came to an end. She moved to Florida; their son, Trey, stayed with him. It was, by all accounts, a shattering breakup. “He loved her deeply, very deeply,” Ann Klenk told me. “He even started writing a book about her. It was a romantic novel, he called it Pursuit.”

Around that time, Danny dropped out of journalism and became a kind of entrepreneur. He started working for, then acquiring, a series of computer and data-processing trade journals. He began making good money, but with daily and weekly deadlines, he had little time for the kind of investigations he once boasted of. By the mid-’80s, after playing the field with a succession of what his friends invariably describe as remarkably beautiful women, he entered into a long-running relationship with Wendy Weaver.

“It was love at first sight for me,” says Wendy, still very starry-eyed about Danny. “He was magnetic, charming, charismatic.”

But then, at the end of the decade, just when it seemed he’d settled down into a comfortable, early middle age, he found himself adrift. He’d decided to sell his chain of computer publications, but according to friends and family, “Danny was really out of his league making the deal. He just didn’t have a business sense.” He walked away with a sum not commensurate with the sweat equity he had put in over the years.

Another friend says that Danny’s bitterness over the deal marked the beginning of “a clear deterioration in his morale. He was not the kind of guy to run around bitterly raging. Danny just internalized. He felt under pressure to make something of himself in a highly achievement-oriented environment.”

Danny set out to settle the score with fete by bagging that One Big Story, the contemporary equivalent of the Inca treasure.

His friends recall an enormously generous guy who’d throw them surprise bon voyage parties and write them soulful birthday poems. “He was someone with an incredible ability to give love, but he had trouble taking it in,” another ex-girlfriend told me.

Clearly, something was missing. And so, in the spring of 1990, Danny set out to settle the score with fate by bagging that One Big Story, the contemporary equivalent of the lost treasure of the Incas.

“This story killed my friend, and I want very simple questions answered …. These people who were jerking him around—whether he killed himself or he was killed—/ still hate them.”

—Ann Klenk

It was Danny’s computer-world contacts that brought him to the INSLAW case, and it was INSLAW that brought him into the ambit—some would say under the spell—of the rogue scientist/weapons designer/platinum miner/alleged crystal-meth manufacturer who sent Danny off on the quest for the grail he was to die seeking.

The INSLAW case alone is enough to drive a sane man to madness, if not suicide. The INSLAW lawsuit has devoured the lives of those involved the way the all-consuming Jarndyce v. Jarndyce Chancery suit devoured its progeny in Bleak House. If they ever make a movie of the INSLAW suit, it could be called Mr. and Mrs. Smith Go to Washington and Meet Franz Kafka.

The Mr. and Mrs. Smith in question are Bill and Nancy Hamilton, an earnest, dedicated St. Louis couple who went to Washington and, in the early seventies, began working on the high-tech side of the war on crime, INSLAW, the software company they built, designed a breakthrough program for use by U.S. attorneys in administering the crime war: it tracks cases, ranking their priorities and helping allocate resources to them. It put INSLAW on the ground floor of a potential quarter-billion-dollar market.

Then, the Hamiltons claim, their company became a crime victim. They charge that elements within the Justice Department—cronies of Reagan attorney general Ed Meese’s—plotted to sabotage their contract with Justice, drive the company into bankruptcy, and steal the valuable software for their own profit. Farfetched as that might sound, back in 1987 a federal bankruptcy judge ruled definitively in favor of Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton, declaring that the Justice Department had used “trickery, fraud, and deceit” to misappropriate the software and then tried to drive INSLAW out of business. (The decision, reversed on appeal, is now heading for the Supreme Court, where Elliot Richardson will argue the Hamiltons’s case.)

But this victory was merely the cue for the real Kafkaesque weirdness to begin. Suffice it to say that the Hamiltons, struggling desperately to escape from bankruptcy, began to suspect there was something larger going on behind the scenes that accounted for what they saw as a pattern of mysterious interventions and string pulling directed against them.

Then along came a master conspiracy theorist who confirmed their darkest suspicion: That they weren’t in the world of Kafka but that of Robert Ludlum. That the alleged theft of their software by Reagan-Meese Justice Department cat’s paws was actually a key element in the hottest new conspiracy theory of them all. He told them that their case was, in effect, the grassy knoll of the October Surprise plot.

His name is Michael Riconosciuto, and he’s the rogue scientist and self-proclaimed former covert operator who became the Hamiltons’s tutor and Danny’s Svengali. (It should be noted that the person who brought Riconosciuto to the Hamiltons’s attention was a key lieutenant of conspiracy-cult leader Lyndon LaRouche; LaRouche intelligence reports were also found in Danny’s files.)

In May 1990, according to the Hamiltons’ internal “Memorandum for the Record” I found in Danny’s files—a memo which became a road map for Danny’s fatal journey—Riconosciuto gave the Hamiltons the following account:

That in October 1980, Riconosciuto was serving as director of research of a weapons-design project operating out of the sparsely populated Cabazon Indian Reservation in the California desert (there were only twenty-four Cabazons living there at the time). That Bill Casey—then Reagan-campaign director, later C.I.A. head—hired Riconosciuto and a Reagan confidant, Earl Brian, to undertake a secret mission to Iran.

Riconosciuto told the Hamiltons that he “did the electronic funds transfer” to convey a payoff of more than $40 million to “certain elements in Iran” to “prevent a deal with the Carter Administration to release the American hostages prior to the election.”

Riconosciuto added that Brian’s reward was a kind of license to grab the Hamiltons’ lucrative software, with the help of Reagan’s Justice Department minions. Riconosciuto further told the Hamiltons that he “saw documents” in the law offices of a former U.S. senator in which the INSLAW-related October Surprise payoff was “chiseled in stone.” (Brian denies all these charges and any connection to the INSLAW case.)

Enter Danny Casolaro. In the summer of 1990, shortly after Riconosciuto had disgorged the details of this story to the Hamiltons, Danny showed up in their offices on K Street in downtown Washington, expressing interest in doing some kind of story on the INSLAW case. And at some point that summer the Hamiltons made available to Danny their twelve-page Riconosciuto memo with its profusion of suggestive and seductive leads, its wealth of references to code names, cover-ups, corporate fronts, cutouts, and covert ops—all of which show up in the notes Danny left behind, many of which go far beyond the October Surprise.

The moment he got his hands on that maddening memo, with its maze of illusion and reality, was the moment Danny’s life changed and he began his descent into the obsession that would lead to his death. He was slowly, then rapidly, sucked into a kind of covert-ops version of Dungeons & Dragons, with that memo as his guide and Michael Riconosciuto as his Dungeon Master.

“Stop it, Danny. Just stop it! Get a job. Just let this goddamn story go.’’

—Ann Klenk

In Danny, Riconosciuto found the perfect audience. The spook and the journalist have always shared an affinity: each thriving in a realm of secrets and lies, cover-ups and cover stories, sharing the romance of the covert mentality, with its thrilling sense of being privy to the secret heart of matters undreamt of by the ordinary, CNN-watching citizen. And both Casolaro and Riconosciuto were in a similar position: lone operatives freelancing on the fringe, longing to be at center stage.

The turning point in their relationship came when a dramatic prediction Riconosciuto made seemed to come true. In February 1991, he told Danny, a high-ranking Justice Department official had warned him not to give a deposition to House Judiciary Committee staffers investigating the INSLAW controversy or he’d end up in jail. Several weeks later, federal agents arrested Riconosciuto on charges of distributing speed. (Riconosciuto, who did talk to Judiciary Committee staffers, insists the chemicals were actually being used in an innovative process for refining platinum ore; the Justice Department official has denied making any threat.) As soon as he got news of the arrest, Danny hopped a jet and flew all night cross-country to Tacoma, where he spent ten days working as an unpaid, unofficial investigator of the Riconosciuto “frame-up”—and of the endless tangled tales of intrigue and dirty tricks this imprisoned Scheherazade of the spook world had to tell.

Not many investigative reporters I knew raised thoroughbred Arabians in the heart of Virginia horse country. Danny did.

“Danny said that when he started out he only believed 5 percent of what I was saying” and doubted 95 percent. “But by the end,” Riconosciuto boasted to me from jail during one of our marathon conversations, the ratio was reversed.

I’d still put his credibility at Danny’s original figure of 5 percent—but even so, the 5 percent that does check out makes Riconosciuto one of the more remarkable characters I’ve encountered in years of debriefing spook types. If he’s a liar, he’s not your ordinary liar. He’s extraordinarily skillful at weaving fact and fiction into a seamless web of seductive intrigue. And he did direct Danny down some dark paths in which he came into contact with some seriously dangerous dudes.

“These people in the desert were murdered. Murder, dope, government. That’s dangerous. Think about it, Danny.”

—Warning from “Clark Gable.”

It was a whipsaw, a psychological whipsaw, Danny Casolaro got caught in. A cruel game of paranoid psych-out played with Danny’s head. The players batting him back and forth were Michael Riconosciuto and his longtime shadow-world nemesis, the man we’ll call, for reasons to be clear soon enough, “Clark Gable.”

But it was no game, it was a long-distance duel. In fact, the only thing the two men agree on is this: Danny’s death was murder. And each implies the other may well have had something to do with it.

Let’s look first at Riconosciuto. Here are some of the things he told Danny—and me—about himself:

That he was a child prodigy who developed a powerful argon-based laser, then went to work in the lab of a Nobel Prize-winning scientist at Stanford at age sixteen. That his grandfather was a top military aide who worked with an early C.I.A. chief, General Walter Bedell Smith—family connections, he said, “opened a lot of doors for me.”

That from Stanford he went on to Haight-Ashbury in the ’60s, where he was responsible for an underground newspaper spread in which, he said, “we published pictures of narcotics agents,” including one “showing [an agent] having sex with these under-age girls that we took from a rooftop.”

Ultimately, Riconosciuto told Danny and me, vengeful narcs engineered his “frame-up” on charges of manufacturing psychedelic drugs.

In Danny’s notes I found evidence that he’d checked out these claims, even getting Riconosciuto’s grades and I.Q. from a parochial school he attended: the I.Q. was a somewhat-less-than-prodigy level 124; the story about building the argon laser is true. But Danny dug up clips which tell a somewhat different version of the narc-sex-vengeance “frame-up.” They report that Riconosciuto was arrested in Seattle in September 1972 by “federal narcotics agents who say they have had the defendant under surveillance off and on since 1968.” What Riconosciuto said back then at his trial was that sinister drug people tried to force him to make psychedelic drugs, threatening to kill him if he didn’t do their bidding. They’d already been “responsible for 14 murders,” he told the court.

That figure—“14 murders”—rang a bell. In my first conversation with Riconosciuto, I was exploring some cryptic but provocative notes I’d found in Danny’s files about “biological warfare” projects. The notes made references to the possibility of manufacturing “slow-acting brain viruses” such as “Mad Cow Disease” which could be slipped into “meat pies.” (Hey, I just report the facts here.)

Riconosciuto was reluctant to talk about the germ-warfare leads. “It’s a real Dr. Strangelove tale,” he said. “But it’s obviously real enough that anybody who’s ever come near it has gotten killed. And Danny was starting to make progress.”

When I asked him to elaborate on the germ-warfare story, he uncharacteristically—or perhaps theatrically—clammed up. “I really don’t want to be the one to say, you know, because I know of fourteen people that are dead that have tried to come out publicly on this.”

While it’s clear Riconosciuto has a special affection for the figure of fourteen deaths, that’s only a fraction of the mortality rate around him, he said. “That’s only on the ‘biotech,’” as he called the germ-warfare stuff. “There’s almost fifty dead total that have been connected with me in one way or another since the early ’80s.”

While this claim captures the paranoid flavor of conversations with Riconosciuto, it’s deceptive in one sense. Because, while there may not have been fifty, or even fourteen, there were some real, documentable murders happening around him, particularly after he arrived at the Cabazon Indian Reservation in the early ’80s and became involved with Clark Gable and ‘‘Dr. John.”

The whole Cabazon-reservation maze Danny was pursuing is further proof that the reality of the covert-ops shadow world will always out-invent the cliches of a Tom Clancy. It is also, to my mind, the strongest barrier to believing Danny’s death was a simple suicide. Regardless of what money problems he had, or book-proposal rejections he suffered, he was really onto a story here.

His investigations were taking him into areas that involved dangerous knowledge and dangerous characters.

Evidence that Danny was onto something real can be found in a frontpage, three-part investigative series in the respected San Francisco Chronicle that appeared three weeks after Danny died and that was inspired in part by his probe into the Cabazon-reservation enigma.

“Just fifteen years ago,” Chronicle reporter Jonathan Littman begins, “a handful of Cabazon Indians barely scratched out a living on their reservation in this tumbleweed desert just north of the Salton Sea,” near Indio, California. But since a “mystery man,” Dr. John Nichols, took control of their affairs as the “administrator” of the tiny tribe, a staggering quarter-billion dollars has been poured into projects based on the reservation.

What Nichols did was leverage the one asset of the woebegone Cabazon band—their “sovereign status” as a quasi-independent nation, which allows them to build casinos and enter into joint ventures with corporations. Such joint ventures are shielded to some degree from the usual legal and regulatory scrutiny, making the reservation extremely attractive to the kind of enterprise which prefers to operate in the shadows. In fact, Dr. Nichols (the doctorate is of divinity) seemed to have close contacts with C.I.A. and military-intelligence operatives (according to the Chronicle, he would tell some that he’d had a hand in the C.I.A. assassination attempts on Fidel Castro and Salvador Allende). Contacts which attracted to the desolate reservation what the Chronicle called “a maze of politicians, military officers, organized crime figures, intelligence agents, foreign officials ranging from Saudi sheiks to Nicaraguan Contras.”

One of the people who materialized in this maze is our friend Michael Riconosciuto. He claimed he’d spent the years since his psychedelic-lab bust as a government informer on the anti-war movement and as a covert C.I.A. operative in South America (where he says he first met Dr. Nichols) infiltrating the liberation theology movement. Back in the States, Riconoseiuto then became the “technical adviser” to mystery man Dr. Nichols on the reservation. Before long, Riconoseiuto says, he began to learn about some “horrible things” going on out there.

This is the labyrinth Riconoseiuto was leading Danny into—the one he died in. The Chronicle reporter tells us that, “just days before his death,” Danny Casolaro “planned to visit the Reservation.

… Although he did not divulge what role the Cabazons may have had in the conspiracy [he was investigating], Casolaro. . . recently told this reporter that one of the titles he was considering for his [Octopus] book was Indio.”

It would have been a more accurate title. Indeed, the grandiose “Octopus” of Danny’s maladroit, overhyped book proposal was—to continue the piscine imagery—a red herring. But there was a lowercase octopus out there in the desert beyond Indio.

Riconoseiuto himself, the resident demon of this labyrinth, supports the more modest, lowercase characterization of the octopus: “Danny’s theory was different” from the typical mega-conspiracy theory, he told me. “Danny was dealing with real people and real crimes.”

One of the crimes was murder. Several murders, all unsolved. One victim was Michael Riconosciuto’s “business

partner,” a man named Paul Morasca, whom he candidly describes as a money launderer. Morasca was found hog-tied and asphyxiated in a San Francisco apartment. One of the initial suspects in the murder was Michael Riconoseiuto himself, and he says the accusation shocked—shocked—him, and motivated him to spill the beans on all the dirty deeds done on the reservation.

He claims he was responsible for pinning a “solicitation of murder” charge on Dr. Nichols for trying to hire a hit man to kill some casino associates on the reservation. (Nichols pleaded no contest and served sixteen months’ jail time on the charge.) A Cabazon spokesman has said, “There’s nothing sinister going on at the reservation. It’s just a very successful operation.”

Anyway, it was in the midst of this film noir intrigue out there in the sterile desert flats that Riconoseiuto first encountered the man who would become his partner, his target, his obsession, and, ultimately, the second pole of Danny’s Octopus investigation: the man we’re calling Clark Gable.

If they ever make a movie of the INSLAW suit, it could be called Mr. and Mrs. Smith Go to Washington and Meet Franz Kafka.

We’re calling him Gable for two reasons: first, because those among Danny’s friends who met this mysterious figure when he flew into D.C., to warn Danny his life was in danger, invariably describe him as “looking just like Clark Gable, only without the big ears,” and, second, because his real name is Robert Booth Nichols, and there already is a Nichols (Dr. John, no relation) in this story.

The circumstances in which Riconosciuto and Gable met are in dispute. But it seems that for a time they planned some R&D ventures for high-tech hardware behind the shield of the Cabazons’ sovereign status. Gable admits to being the head of a holding company, one of whose subsidiaries has licenses on the prototype for an automatic weapon. But he won’t say much more about his business. When I finally reached him at a California number I’d found in Danny’s notes, he denied any involvement in improper activities. He told me his falling-out with Riconoseiuto began at the reservation when he caught the self-styled scientist in “lies” about his esoteric inventions. He blames Riconosciuto and others who have been “Michaelized” for peddling dark tales about him. He hedged when I asked him about intelligence-world connections. “I have been involved in sensitive activities. That’s the only way I can describe it,” he said. And while he denied being in the C.I.A., he said he’d “been involved with a lot of people who tell me they are in the C.I.A., although I have no way of substantiating it.”

What is certain is that Michael Riconosciuto has it in for Gable, and that he began pointing Danny in Gable’s direction, filling his head with allegations of Gable’s sinister, international covert world connections. Indeed, he began to paint a picture of Gable that linked him to very big, very dangerous organized crime syndicates, including the feared Japanese Yakuza and the fearsome Gambino crime family of John Gotti. That linked him in addition to various C.I.A. and British intelligence plots, because Gable was the friend of a legendary Bond-ish Brit known as “Double Deuce.” (Are you beginning to get a feel for the texture of Danny Casolaro’s world by now?)

In fact, Riconosciuto attempted to convince Danny, with some success for a while, that this man Gable was the key to what Danny was starting to call the Octopus.

According to an ex-F.B.I. man who was a source for Danny in his final weeks, Danny began rashly and unwisely calling Gable himself about these allegations. “Danny began getting into areas that were dangerous, very dangerous,” the ex-F.B.I. guy told me. “This is dangerous work. He was warned. You know. Gable warned him.”

A VISIT FROM CLARK GABLE

I have the details of the strange encounters between Danny and Gable from three different sources, none of whom was eager to be the sole source.

Because all recalled them as chilling. The exotic quality of those meetings is captured by one of Danny’s friends, who had lunch with Danny and Clark Gable. Gable had flown into Washington, D.C., on a weekend about a month before Danny’s death, was staying at the top-bracket Four Seasons Hotel in Georgetown, and seemed to have little business other than to spend time with Danny Casolaro.

The friend, a well-connected player in Pacific Rim politics who requested that his name be withheld, said Gable was “very slick, very civilized-appearing. Danny used to say he had the manners of a gentleman, but underneath he was a thug.”

The friend recalls Gable “doing that thing that guys do on barstools the world over. He looks at you with that wink and says, ‘You know, I’m not in the C.I.A.’ “

When the three of them finally sat down to lunch at Clyde’s in Tyson’s Comer, the friend says, Gable promptly informed them he’d “just taped a radio broadcast as the incoming minister of state security in Dominica, and was preparing a coup that ‘some bimbo in the C.I.A.’ was asking him about. But he was actually at a higher level than the ‘bimbo.’” (The island of Dominica, which figures heavily in Danny’s notes, is an impoverished flyspeck in the Caribbean that has been characterized as “the Third World’s Third World.” Gable says he was asked by the leader of the opposition party on the island if he’d become security minister, should an election bring it to power; he says he cleared this with the State and Justice departments. He also denies any C.I.A. coup plot and says the broadcast was an interview about economic development.)

Danny’s friend says he “never witnessed a performance” like the one that ensued. “[Gable] had this story that they were going to turn Dominica into a C.I.A. base, had plans for a desalination program, and pulled out this design drawn by a French architect of a dome the size of Texas Stadium that was half underwater. Really, the whole thing reminded me of Ernst Stavro Blofeld [the Bond villain], I mean, good Lord, you could just see James Bond swimming out there with a babe. I excused myself at this point. I really didn’t want to hear anything more after seeing Blofeld’s underwater lair.”

“Did he come across as a con man?” I asked Danny’s friend.

“It’s funny,” he said. “It was like he was real slick, really like Clark Gable, and there were nuggets of truth. The guy just oozes intrigue.” (Gable told me he was exploring plans for exploiting the island’s heavy rainfall to export purified water, and denies anything improper about it.)

Then, the friend says, Danny showed him a side of Gable he didn’t want to know about.

“After lunch Danny pulls me aside and pulls out this purported F.B.I. wiretap summary on [Gable], and it showed how [Gable] is connected. It linked him to the Yakuza and to the Gambinos as a money launderer. And that widened my eyes. I said, ‘Danny, I’m gonna take you out back and whip your ass! You just put me in a meeting with this man and didn’t tell me what the hell—why didn’t you tell me before?’ And Danny was kind of, ‘Oh, I don’t know. I wanted to see how [Gable] would react.’ In other words, he gaffed me with a hook and tossed me in the water to see if the Octopus would move!”

Gable says the suggestion that he’s involved with the Yakuza and the Gambinos is “totally false.” It’s “absolutely ridiculous” to link him to “the Gambia family,” he told me, conspicuously mispronouncing the name. He traces the trouble to an F.B.I. misunderstanding of his screenplay career. He says he was introduced to a high-level executive of MCA several years ago at a coffee shop. When the MCA man encouraged him to turn some tales he’d told him into screenplays, they became friends and, briefly, business associates. Unknown to him, the MCA man was the subject of a full-court-press F.B.I. investigation for being a key organized-crime link to the entertainment industry. And so, Gable says, his voice was picked up by taps on the MCA man’s phone. The bureau misinterpreted their conversations as containing code words for illegal activities, turned around, targeted him, and slandered him to his business associates. In fact, Gable’s company is suing an F.B.I. man for libel and slander. He says that the wiretap summary was part of the F.B.I. man’s affidavit in the Gable slander suit.

In addition to the dispute over the wiretap affidavit, there’s also a dispute over the nature of the warning Gable gave Danny. Riconosciuto, who wasn’t there, tries to portray it as a personal threat from Gable. But others recall that it was Gable warning Danny against Riconosciuto.

Danny’s girlfriend Wendy Weaver, for instance, spent a long, strange evening with Danny and Gable and has an indelible memory of the warning.

“It was a weird night, so weird,” she recalls. “We met at the Four Seasons [bar]. He was pretty well lit when we got there. He was very charming, very handsome. When I tried to find out who he really was, he really didn’t give me an answer. He just started these warnings …. He kept saying, ‘You don’t know how bad this guy Riconosciuto is. Tell Danny to stay away.’ He said, ‘Riconosciuto—he might not get you today, he might not get you next month. He might get you two years from now. If you say anything against him he will kill you.’ “

He repeated it several times, Wendy says. “At least five times.’’

Later in the evening, Wendy reports, there was a heated altercation with “this

The only thing his two chief sources agree on is this: Danny was murdered. And each implies the other may well have had something to do with it

Asian-looking guy, who apparently insulted me in some way. And Danny was scared. After we got rid of [Gable], Danny goes, ‘Wendy, this guy is scary.’ That’s the first I heard him say that.”

While Gable was trying to warn Danny about Riconosciuto, Riconosciuto, for his part, was desperately trying to warn Danny about Gable. Or so he says. “I was absolutely frantic trying to warn him,” Riconosciuto told me.

It was Danny’s habit of “bouncing” Riconosciuto’s stories off Gable that put him in peril, Riconosciuto says. One of the things he was supposedly “bouncing” involved what Riconosciuto said was a major heroin-related sting. (Gable denies any involvement in drug traffic. “I hate narcotics,” he told me.) Another involved Riconosciuto’s claims about an effort by the Cali cocaine cartel to derail the extradition of an alleged Colombian kingpin called Gilberto.

Gable just “went ballistic,” Riconosciuto says, when Danny bounced this Gilberto matter off him. “But by the time I heard about it, there was nothing I could do, you know, except to warn Danny.

“And I called from that day on—it was on a late Monday—Tuesday, Wednesday, all the way through the weekend when they found Danny. Every day I was calling the Hamiltons, asking if anybody had heard from Danny. And I was frantic.”

MAD COW DISEASE AND A BLAZE OF GLORY

What was going on in Danny’s head as he was being whipsawed between these two shadowy operators and their death warnings?

There was one point in my immersion in Danny’s mental world when I felt a flash—a brief, chilling, but illuminating flash of what it must have been like for him when he got in too deep. It came in the course of a phone conversation I had with Ann Klenk, who was not only one of Danny’s oldest and closest friends but also the one whose skeptical perspective on his obsession I’d come to rely upon.

She was telling me of her surprise and puzzlement over something she’d just learned: that not long before his death Danny had approached a nurse he knew and questioned her closely about the symptoms of multiple sclerosis and brain diseases.

This was particularly pertinent to the murder-or-suicide question, because an autopsy examination of Danny’s brain revealed possible symptoms of M.S. Initially, his friends and family had dismissed this as irrelevant—it couldn’t be a motive for suicide, because Danny had never complained of symptoms or, to their knowledge, known of the disease.

Then I mentioned to Ann the cryptic notes I’d found in Danny’s files: on germ warfare, on slow-acting brain viruses like Mad Cow Disease, about targeting people with them by slipping them into meat pies.

That’s when it struck me. “Oh, God,” I said to Ann, “Danny’s asking a nurse about brain disease—maybe he thought he’d been targeted.”

Had he gone that far, or was I now too far gone down the road to paranoia that he’d traveled?

A few days later, I happened to mention the report of Danny’s seeking information about brain-disease symptoms to Michael Riconosciuto. Who promptly said, “Oh, yes. He, uh, was concerned. And that was one of the reasons he had such an obsession [with this story]. Because he felt he had been hit by these people.”

“Hit by them?”

“He confided this to me to try to get me to talk further” about biological warfare projects he’d discovered, Riconosciuto explained. He’d been warning Danny that he wasn’t appreciating the danger his investigation was exposing him to. “I told him, ‘You can’t envision your own death. Why would you want to do this [kind of reporting]?’ And he finally came out and said, ‘I’m going to die anyway and… I want to go out in a blaze of glory and take them with me.’ “

What did he mean, he was going to die anyway? I asked Riconosciuto.

“He suspected that he had been, you know…a source told him that he, among others, had been targeted with this sort of [slow-acting virus] thing.”

This was too much even for Riconosciuto. “I told Danny, ‘Look, the paranoia will consume you. You need to go and get tests.’ And Danny went and got tests and they were inconclusive. Now, what he probably had was the genesis of a naturally occurring ailment.”

The paranoia will consume you. This exchange marks the moment when Danny’s conspiracy-obsessed imagination surpassed even that of his most inventive source. In fact, the definition of true paranoia might be the point where Michael Riconosciuto says you’re too paranoid for him.

And yet, there’s something in Danny’s reported remark that caught my attention: Riconosciuto’s recollection of Danny’s saying, I want to go out in a blaze of glory.

Certainly, as it turned out, Danny went out in a blaze of publicity. The networks, the magazines, the mainstream reporters who had given him the brushoff in the weeks before he died, gave him star treatment as a corpse. ABC’s Nightline and CNN assigned swAT-team investigative squads to follow the leads in his notes. He couldn’t have had it better if it had been scripted.

Could he have scripted it?

More than anything, it’s the conspicuous theatricality of Danny’s behavior in the last ten days of his life—when he suddenly went into his “I’ve cracked the whole case” mode—that led me to reluctantly revive consideration of what might be called “the Gatsby scenario”: that his death was a final act of selfcreation.

What ultimately led me back to the Gatsby scenario was the inadequacy of both the case for murder and the case for simple suicide.

One can certainly understand why almost every one of Danny’s friends and family leans toward the murder theory. (His mother’s first reaction when she heard the news: “They’ve killed him!”) They knew he’d been getting warnings. They knew he’d been getting threatening phone calls. On the Monday before the Saturday he died, he told his brother, “I’m getting these strange phone calls saying, ‘You’re gonna die.’” Also that week, shortly before he left on the fatal journey to that West Virginia motel, the neighbor who looked after his house reported answering Danny’s phone and hearing a voice saying, ”You’re dead.” She reports a similar “You’re dead, you son of a bitch” call hours after his body was found—which rules out Danny himself as a possible source of the alleged threats against him.

And then there was the unmistakably clear—at least on the surface—prophecy to his brother: If anything happens to me it won’t be an accident.

With admirable dedication, Danny’s younger brother Dr. Tony Casolaro has made it his mission to ensure that there is any truth to this he will make certain it gets out. Which has resulted in this soft-spoken, reserved specialist in pulmonary medicine—quite the opposite of the extroverted, gung ho party dude Danny was—plunging into his dead brother’s world.

He’s talked to Clark Gable. He’s even taken collect calls from Michael Riconosciuto in which Danny’s jailbird Svengali spun out his “fentanyl” theory: that Danny was immobilized by the powerful synthetic heroin-like drug fentanyl, and then, in a state of compliant, semi-paralyzed alertness, was forced to cut his own wrists.

After spending weeks on his brother’s case, Tony Casolaro is tom. He can’t believe it’s suicide, because his brother was so excited and upbeat about his investigation on that last Monday he saw him.

Tony is also troubled by a number of facts. Papers and files Danny had been seen with up in West Virginia were missing from his motel room. Stolen by his murderers? (Of course, if Danny wanted to create doubt he could have made a point of “disappearing” the papers before killing himself.) Then there are the still-unexplained phone calls from people who seemed familiar with the implications of Danny’s death before even the police knew. There was the hasty embalming, the cursory look at the death scene by the cops, who made an initial judgment of suicide. (The reinvigorated Martinsburg police investigation—ongoing as of this writing—has been far more thorough, but perhaps too late.)

But, on the other hand, Tony knows the actual scenario for murder is “kind of Tom Clancy-ish. ‘‘

“The way I envision it could have happened,” Tony told me over dinner one night in downtown Washington, D.C., “someone stands over him and says, ‘You write this suicide note or my partner who’s standing with your son will, you know, [kill your son].’ And Danny would just go, ‘Fine.’ ”

Danny was a big, tough guy, a boxer, fearless, Tony says. But if he felt his son’s life was being threatened, “he wouldn’t be someone who would resist that kind of pressure.”

Having written the suicide note, this murder scenario goes, Danny would then have run the bath, gotten undressed, gotten in, and started carving up his wrists with the blade his captors provided him.

The reason his friends and family, all solid-citizen types, could believe in such a farfetched scenario is precisely that Danny made such a big point of telling each of them in the week before his death that he was on the verge—or over the verge—of the big breakthrough he’d been looking for. That he was about to go to West Virginia to “wrap it up,” to get the final piece of the puzzle, to nail it once and for all. He told one friend he was going to West Virginia “to meet the head of the Octopus.” He told another he was going to West Virginia to “bring back the head of the Octopus.”

Riconosciuto was reluctant to talk about the germ-warfare leads. “Anybody who’s ever come near it has gotten killed.”

The exact nature of the breakthrough he was trumpeting seemed to vary. He told three people he had finally solved the whole insanely complicated INSLAW mystery. He gave two other friends the impression that he’d gotten the goods on the October Surprise case and linked it to B.C.C.I. He told a source he met in West Virginia that he’d just “gotten enough information on B.C.C.I. to hang Clark Clifford.” He went through an elaborate charade with the two friends —showing them a key document that he said tied it all up. The document was a photocopy of a $4 million check signed by Adnan Khashoggi, the Saudi arms dealer who’s been linked to Iran-contra. The check, copies of which I found in his files, is made out to Manucher Ghorbanifar, the shadowy Iranian exile arms dealer who played a mysterious role in the Iran-contra deal.

“He was really excited when he got that,” Danny’s friend Ben Mason told me. “It was like, ‘This is it!’”

Was this the magic document/smoking gun of the whole October Surprise/B.C.C.I. /Iran-contra mega-conspiracy?

That’s what Danny implied to his friends. Mason, a musician who wrote songs with Danny, is still under the impression that the discovery of the check was a scoop, a Danny Casolaro exclusive. But, as it turns out, the check had been made public by the congressional Iran-contra committee in 1987 and was well known to reporters in the field.

Ben Mason says that the real bombshell significance of the check is in its link to another document Danny showed him on the eve of his West Virginia trip: a passport photo of an Iraqi named Hassan Ibrahim, a reputed arms dealer. There are those who say that it was Ibrahim whom Danny was going to meet in West Virginia, that it was most likely Ibrahim who was the mysterious “Middle Eastern-looking man” Danny was seen with in the bar of the Sheraton Martinsburg the day before he died. But thus far nothing solid has turned up to suggest the whole magic “Missing Link check” act was anything other than a creative leap of speculation by Danny— if not a deliberate charade.

It should also be recalled that Danny was a novelist. And that he’d spoken to a number of his friends about possibly telling the whole Cabazon-Octopus story as a novel. His theatrical “I cracked the case” declarations in that final week suggest the thriller-novelist imagination at work, setting the stage for the obligatory mysterious murder essential to every spy thriller—in this case, his own.

The timing for all this is notable. The sudden flurry of melodramatic “I cracked the case” calls began at the end of July, shortly after Danny’s nonfiction-Octopus-book proposal was rejected by the first mainstream publisher he sent it to, Little, Brown. One friend Danny called that final week remembers him “planting the seeds” earlier that summer. “Danny began telling me about these death threats he was getting on his answering machine,” the friend says. “And I said, ‘Look, Danny, the telephone company can find ways to trace these calls.’ And he got very embarrassed.”

Meaning he faked it? I ask.

“Right.” This friend’s theory is that Danny knew he was suffering from some progressive debility, like M.S.— there’d been several “accidents” involving Danny’s muscle coordination. That Danny knew he wouldn’t or couldn’t ever get his book written, in part because he wasn’t sure what he really had. ”What he did is throw a whole issue up against the wall so that it would be sorted out in some fashion.” The friend believes that if Danny staged his death to look like murder, it would be “tragic,” but also a “very wild, courageous,” desperate attempt to get the truth out.

Then why leave a suicide note? Ann Klenk asked. It’s a cogent objection. If he’d left no note, or, she suggests, if he’d driven his car off a cliff, or jumped off a building, then people would be more likely to speculate he’d been run off the road like Karen Silkwood, or he’d been pushed off the building he “jumped” from. She thinks if it was suicide it may well have been because “Danny finally found it all a crock,” because the whole thing was “LaRouche sickthink, doublethink,” and disinformation.

Some, however, cite the note itself as a clue to the murder. The note read, “To those who I love the most: Please forgive me for the worst possible thing I could have done. Most of all I’m sorry to my son. I know deep down inside that God will let me in.”

Several of Danny’s friends have told me emphatically that that last line— “God will let me in”—is the tip-off. That Danny, a Catholic, knew that suicides could not be “let in” to the Kingdom of Heaven. And that by including that line, by saying he would be “let in,” he was signaling—under the noses, or under the guns, of his captors—that his death was not suicide.

Perhaps. But the best response to Ann Klenk’s contention that he wouldn’t have left a suicide note if he had wanted people to think he’d been murdered is, well. . .the actual reaction to his death. A VICTIM OF “THE OCTOPUS”? asked Newsweek in a full-page takeout. THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH? asked Time. CLOUDED IN MYSTERY, People said darkly two months after his death.

And that’s only the mainstream media. Among the conspiracy theorists it’s already an article of faith that Danny was assassinated. “A government-sanctioned hit,” declares Virginia McCullough, a California-based October Surprise-conspiracy specialist who exchanged notes with Danny before he died. She says Danny was just the latest of several reporters murdered because of their October Stir prise investigations— all ‘‘government hits.” Riconosciuto has added Danny’s body to the fifty he says were murdered because of their proximity to him and his schemes. Danny’s missing files have already begun to assume the all-purpose, prove-anything status of such other totems of conspiracy theory as the eighteen-minute gap on the Watergate tapes, the stolen papers of Howard Hughes, and the missing diary of Mary Meyer (the murdered J.F.K. mistress).

Several of Danny’s friends have told me emphatically that the last line of his suicide note is the tip-off.

And Danny himself—the reality of who he was and what he was really after— has begun to be subsumed by his enshrinement in the rolls of the martyrs to the great Octopoidal conspiracy in the sky.

That evening, in my room at the Sheraton Martinsburg, I climbed out of the bathtub. You stare too long at that cottage-cheese ceiling and you begin to see patterns coalescing in the pockmarked surface.

I sat down at the functional desk, trying to ignore the heavy-handed irony of the hotel’s promotional card in front of me. It showed a picture of a knotted rope being stretched taut between two fists. This trip probably has you tied up in knots. . . . If you’re at the end of your rope, give us a call. It was an ad for the hotel’s massage service.

I tried to imagine Danny Casolaro at the end of his rope, stretched to the breaking point by his two sources, staring at that knotted cord.

For about the tenth time in the past twenty-four hours, I opened up Danny’s last surviving notebook, one of those cheap composition notebooks with a speckled black-and-white cover. On the inside cover was a date: August 6, four days before Danny died. Wendy Weaver had just located it and supplied it to me, along with ten loose pages of notes which had not previously surfaced.

The notebook itself had only one page written on by Danny. There was only one substantive note:

Bill Hamilton Aug. 6

M.R. … also brought up Gilberto.

This is an apparent reference to the alleged Cali-coke-cartel kingpin who figured in the last murky Michael Riconosciuto quest Danny was pursuing.

What caught my attention were the two names and phone numbers on that page, above the note, under the heading “To Call.”

One name was “Jonathan,” apparently Jonathan Beaty, the reporter who broke Time magazine’s story on alleged B.C.C.I. hit squads.

The other was “Ron.” Followed by my phone number.

He didn’t call, but I suspect that if he’d reached me in the forty-eight hours before he left for Martinsburg he might well have told me some version of the “I finally cracked the case” riff. And I suppose if I’d heard it, it would have had the same effect on me: I would have been far more predisposed to believe the murder theory.

There is, of course, a legitimate, even compelling reason to pursue every piece of missing evidence, every discrepancy, every unexplained circumstance surrounding Danny’s death—the reason Jack Anderson, dean of investigative columnists (who believes it’s likely that Danny was murdered), gave: “Anytime a reporter is found dead while covering a story, it’s a threat to all of us until the truth comes out.” I don’t think we should close the book on Danny Casolaro until we rule out the murder theory. Just as maybe a disturbing 5 percent of what Michael Riconosciuto says is credible, I’d say there’s still a disturbing 5 percent chance that Danny Casolaro was murdered.

But I do have my own theory about what really killed Danny Casolaro. And the larger lesson his death has for us.

I believe that, in a sense, Danny was correct when he worried he might have been “targeted” with a “slow-acting brain virus.” Not exactly the organic virus he worried about, not Mad Cow Disease or multiple sclerosis. Rather, I believe what destabilized Danny was an extremely virulent strain of the information virus we’re suffering from collectively as a nation: Conspiracy Theory Fever. A slow-acting virus that has infected our ability to know the truth about the secret history of our age.

Don’t get me wrong: I believe there are real conspiracies—Watergate was one; Iran-contra and C.I.A./Mafia plots against Castro were others. But those in the grip of Conspiracy Theory Fever seem compelled to believe that (to paraphrase the Flannery O’Connor title) everything that conspires must converge. That all conspiracies are tentacles of one big Octopoidal conspiracy that contains and explains everything.

The chief symptom of slow-acting brain viruses like Mad Cow Disease is that the brain becomes “spongiform,” riddled with holes. The chief symptom of Conspiracy Theory Fever is that the brain becomes too sponge-like, too absorbent, indiscriminately accepting all facts and conjectures as equals, turning coincidence into causality, conjectures into certainties.

It’s clear that toward the end Danny Casolaro fell victim to this kind of fever. He couldn’t be content with the lowercase octopus of the Cabazon-reservation maze. He somehow had to convince himself and the rest of the world that he’d come upon the mega-conspiracy that explained everything. Even if he died trying.

Certainly a share of the blame for conspiracy fever must go to spooky sources like Riconosciuto and Clark Gable, to the LaRouchians, to paranoids-in-power like C.I.A. counterintelligence guru James Angleton, to the overly credulous Christie Institute types. And to the mainstream media, whose inadequate performance on the key scandal nexuses of our time have left the field open to the paranoids and opportunists who populate it with phantom Octopi.

Still, I think of Danny Casolaro not as a paranoid or opportunist but as a kind of Gatsbyesque conjurer, a feverish romantic illusionist.

The far-off glow Danny Casolaro yearned for was the illusory Ultimate Story, the one that would illuminate the source of the ongoing American nightmare. It was an illusion Danny loved so much he may well have given his life to make it seem true.