George Kimball hung upside down some seventy feet in the cold Manhattan air, still in need of a cigarette. Well, the doctors had said smoking would kill him, hadn’t they? The previous autumn, they had found an inoperable cancerous tumor the size of a golf ball in his throat and given him six months to live. Five months had passed. He’d finished his latest round of chemotherapy, and now George, sixty-two years old and recently retired from The Boston Herald, was at the Manhattan Center Grand Ballroom in 2006, to cover a night of boxing for a website called The Sweet Science.

He’d never set foot in the place before. He didn’t even know what floor he was on when he went for a smoke between fights. There was a long line at the elevator so he went looking for a backstage exit and stepped out into the winter night, onto a tiny platform seven stories over the sidewalk. And then, as George would later tell the story, he plunged into darkness.

His leg caught between the fire ladder and the wall. He knew right away it was broken. He dangled from the fire escape like a bat—except bats can let go. He tried calling for help but his voice was too weak from the cancer treatments; he could barely whisper. Also, he wanted that fucking cigarette. A security guard, ducking out for his own smoke, found him, and it took another twenty minutes before the paramedics could get George on his feet. They wanted him to go to the hospital for X-rays but George talked them out of it. His wife was a doctor, he explained, and with all the chemo, he had more than enough painkillers at home.

He went back to his seat to watch the last two fights. Afterward, he hobbled to a drug store and bought a knee brace, an ice pack, a large quantity of bandages, and a lighter to replace the Zippo he lost in the fall. Two days later George would go to a hospital to set his broken leg. But that night, he went home. His wife Marge cleaned the scrapes on George’s arms, and he took a big hit of OxyContin. Then he filed his story on the fight.

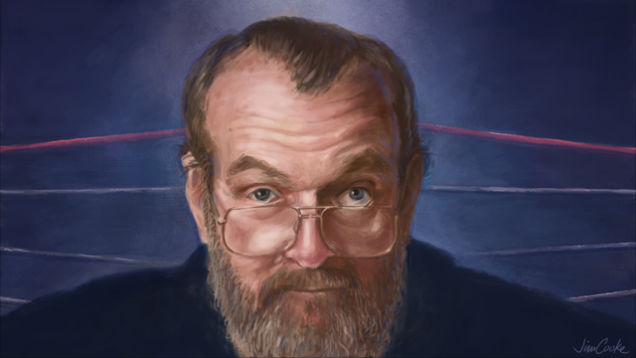

George was a large man with one good eye, a red beard, a gap between his two front teeth, and a huge gut. He was a literate, two-fisted drinker who never missed a deadline and never passed up an argument. One night, when he was twenty-one and partying in Beacon Hill, he was struck on the side of the face with a beer bottle. That’s how George got his glass eye.

It became his favorite prop. “You’d be amazed,” he said, “by how many people ask you to keep an eye on their drink.”

George began his career when Red Smith and Dick Young were the lords of the press box. On the night he fell out of the Manhattan sky, he had been a sports columnist for close to forty years, “the last of his kind,” according to Michael Katz, the longtime boxing reporter for The New York Times. He drank one-eyed with Pete Hamill and Frank McCourt, smoked dope with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, and did with William Burroughs and Hunter S. Thompson whatever was in their heads to do at the time. George covered Wimbledon and the Masters, the World Series and the Super Bowl and more than three hundred championship fights. He golfed with Michael Jordan and sat in a sauna with Joe DiMaggio. “He’d show up with Neil Young,” Katz said, “and get drugs from the Allman Brothers. Mention a name and he’d somehow know the person.”

He loved being around celebrities. The walls of his home office were covered with framed pictures: George with Marvin Hagler and Mike Tyson, George with Muhammad Ali, George with Phil Mickelson, George with Bo Derek. His daughter, Darcy, remembered all the times her father would approach someone famous: “I would brace myself for an awkward moment, and the celebrity would call out to him first: ‘George! Long time no see.’”

It might look like an enviable life; then again it might also look empty. For all the drinking and drugs and Hunter Thompson-style wild times, the Hunter Thompson-style bestsellers were never there. Nothing but soft pornography (Only Skin Deep, 1968) and a sports book (Sunday’s Fools, 1974), co-written with Patriots tight end Tom Beer. A single poem in the Paris Review. He drank, he smoked, he ate sticks of butter with mashed potatoes in a river of ketchup, slept in a coffin over McSorley’s tavern, and fretted that he’d never written a meaningful book. It wasn’t just the booze and drugs that got in the way; it was life on the road: the next fight, the next deadline, the next bar, the next party. “He was always impatient to get to the next thing,” said Jenny Dorn, the wife of the poet Ed Dorn, an old friend of George’s, “which is why a newspaper was the ideal place for him. Maybe he felt safer in that realm to avoid something else.”

George didn’t think he’d live past forty and nobody who knew him ever got the feeling that his work had his full attention. “He was never ambitious,” remembered his friend Bill Lee, the pitcher for the Boston Red Sox. “He was just there for the moment.”

But he lived beyond his wild years, and when his time grew short, it turned out that George had more than a trace of ambition left. He burned to leave something that would last.

By the time I met George he had lost his famous gut. I saw him at a reading for his book Four Kings, George’s account of the middleweight rivalry between Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler, Tommy Hearns, and Sugar Ray Leonard. It was the fall of 2008. Not long after, he invited me to a screening of Fat City, John Huston’s movie adaptation of Leonard Gardner’s peerless boxing novel. He was in good company, joined by his old friend Pete Hamill. They stood on the sidewalk before the movie started and smoked cigarettes. George didn’t wait more than a minute after finishing a Lucky before he lit another one. Someone said to him, “George, don’t you think you should quit?”

He looked up at them with a crooked smile. “Why?” he asked. “Is it going to fucking give me cancer?”

In a letter to George, Hunter S. Thompson wrote, “I want Wenner to have the experience of dealing with someone more demonstrably crazy than I am.”

When I edited a book of essays about Yankee Stadium, George contributed a gem about a brawl between the Yankees and Red Sox in 1977. Bill Lee got body-slammed to the ground by Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles and then made the mistake of getting up.

“In Nettles’ defense,” George wrote, “what he probably saw was just a crazy man charging at him. In any case, when Lee got close enough, Nettles cut loose with a right cross, and when Lee tried to block it with his left, he discovered that he couldn’t lift his arm above his waist. The punch caught Spaceman flush in the face dropped him in his tracks.

“A few months later, Ali and Ken Norton fought in almost exactly the same spot, and in fifteen rounds neither one of them landed a punch as hard as that one.”

George and I started a correspondence. I can’t pose as a close friend because I only got to know him in the last few years of his life. I had heard stories about him—about how he was buddies with Thompson and how he got in a screaming match with Norman Mailer; about how he once called former New York Mayor John Lindsay a tight-assed WASP to his face (and then smudged cigar ash on Lindsay’s forehead); about Kimball’s fourth marriage ceremony, at which George Foreman officiated. But mostly, I was intrigued that George was still writing despite suffering from cancer. What was behind this uncharacteristic burst of ambition?

George Kimball III was born on December 20, 1943, the son of an Army officer whose career took his family to Taiwan, Germany, Kentucky, Maryland, Texas, and Kansas. He was the oldest of seven children, and his parents doted on him. When he was two, his father took out a set of cards with national flags on them and taught him to name all the countries. He was always willing to perform the feat for guests.

George was a tall, thin boy, a natural athlete. He ran track and played football and basketball in high school. He was also a voracious reader who spent most of his time in the library and seemed to retain everything he’d read. “I expected him to be a writer,” his mother said. “In first grade, he signed his papers, ‘George Edward Kimball, the Third.’”

But George was a lousy student. One year he was at the University of Knsas on an ROTC scholarship, the next at a community college outside of Boston, then back to Kansas, then to jail after an arrest in 1965 at an anti-war demonstration for carrying a “Fuck the Draft” sign.

“George was one of the first hippies,” said his brother, Rocky. “He was listening to folk music, hanging around beatniks, and involved in radical politics.” Fuck the Draft didn’t reflect well on his father, a colonel with ambitions of retiring as a general. By this time, sports were all father and son could discuss without arguing. His mother, however, was unreserved in her affection—no matter where he was, she sent cartons of Lucky Strikes as care packages.

George moved to New York and got a job working as a junior assistant for the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, where he met Hunter Thompson. He became a regular at the Lion’s Head Tavern in Greenwich Village, the walls there covered with the jackets of books by regulars like Pete Hamill, Joe Flaherty, and Leonard Shecter. But writing was hard and drinking wasn’t. “You didn’t go to the Head at night to improve your work habits,” Hamill said.

George moved out of his sublet above McSorley’s in August 1968. “Nothing really promising loomed on the horizon,” he said. Ted Berrigan, an accomplished poet in the New York scene and a friend, “was headed out to Iowa to teach,” said George. “After receiving encouragement from the people in charge of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop they assured me that I’d be not only welcomed there but would have funding too. Big mistake. I should have gotten that in writing.”

He worked on a second novel. Robert Coover was his thesis adviser, but George told me he didn’t consult Coover much because they didn’t see eye to eye. During the holiday break, George drove back to New York to talk about the book with Maurice Girodias, the owner of Olympia Press (which had published Only Skin Deep). Girodias “thought it wasn’t dirty enough but grudgingly gave me a few hundred up front,” George said. “In the end I junked the book.”

He stayed at Iowa for a few semesters then left and never talked about it. His sister, Jenny Kimball, was blunt about that opportunity. “He squandered it.”

“Douglas County needs a two-fisted sheriff.”

Soon, George was back in Lawrence, Kansas, this time with the idea of running for sheriff. It was “high camp and theater,” he recalled. He’d spoken to Jerry Rubin about it in New York without knowing that Hunter Thompson would run for office in Aspen, Colorado, that summer. In spring 1970, George announced that he would run as the Youth International Party candidate against the incumbent, Rex Johnson, a Republican who had run unopposed for years and who had arrested him back in ‘65. George waited until a half-hour before the deadline and filed as a Democrat; if he’d done it any sooner the party would have found somebody else.

He wore a tin badge and carried a rusty old six-shooter. He declared that the only laws he’d enforce regarding the “drug problem” would be “fraud, truth in packaging, and price-fixing conspiracy statutes against unscrupulous dealers.” He announced he’d appoint African-Americans to half the deputyships and said that the state attorney general “harbored a predilection for engaging in unusual activity with livestock.”

“You can never be sure you know when George Kimball is taking himself seriously,” Bill Moyers, LBJ’s White House press secretary and later a journalist, wrote in Listening to America: A Traveler Rediscovers His Country. “You are not even sure he knows. But enough townspeople take him seriously to give him stature with the street community.”

During his campaign, George made the local papers when he was arrested at a demonstration in Topeka for obscenity, one of several times he found himself in jail. He was even featured in Time. His parents displayed a copy of the magazine without shame. “They appreciated the attention he got,” said his sister, Becky, “if not the reasons for it.”

Johnson had a withered right hand and George’s slogan was, “Douglas County needs a two-fisted sheriff.” Johnson won by a landslide and George lit out for Boston. The sheriff’s assessment: “He wasn’t the worst son of a bitch I ran against.”

Hunter Thompson lobbied Jann Wenner, the publisher of Rolling Stone to hire George, who had been writing freelance music reviews. In a letter to George, Thompson wrote, “I want Wenner to have the experience of dealing with someone more demonstrably crazy than I am—so that he’ll understand that I am, in context, a very reasonable person.”

Wenner apparently felt one Hunter Thompson was all he needed, so George headed instead to the Boston Phoenix, that town’s version of the Village Voice. It was the ideal place for his freewheeling reviews of poetry, books, and music. His passion, however, was sports.

“At least once a week someone asks me why I write about sports,” George wrote in a column. “My friends on the Left persistently refer to the ‘pig mentality’ which governs organized sports and want to know how I can fathom sharing the delectations of Richard Nixon. On the other side of the spectrum—people I run into in bars, and not a few brethren sportswriters (many of whom have closer ties to the management and/or ownership of various teams than I) are wont to ask, ‘If you hate sports so much, why the hell do you write about it?’”

There were other young Turks on the scene, the Globe’s Leigh Montville, Peter Gammons, and Bob Ryan among them, but none as worldly as George. His reputation preceded him and he played on it, unnerving the management of the local teams, particularly the Red Sox, because he was getting stoned with players like Bernie Carbo, Fergie Jenkins, and Bill Lee. Bob Sales, the editor of the Phoenix in the late seventies, remembers coming into his office to find George passed out on one couch and Lee on another.

“My favorite story about him came to me second-hand from Phoenix vets,” said the writer Charlie Pierce, who worked with George at the paper. “One week, George came in and typed up his piece, dropped it at the editor’s desk, and went off into the night. The editor looked at the copy and it was utter gibberish. Lots of consonants. Remembering that George was a touch-typist, the editor took the piece, put his hands on the keyboard, but moved them one key to the side. The piece was perfect, except George had started one key over.”

The story became legend, and George later confirmed it—sort of. Loath as he was to let the facts stand in the way of a good yarn, he allowed as how it might’ve been one paragraph he mistyped, not the whole story.

Though away from his typewriter he was a maverick, George’s prose style was clear, full of mordant observation, almost traditional, not at all like that of his gonzo friend Thompson. “He was a tremendous reporter,” said Michael Katz, “not only one of the best, one of the fastest.”

George once wrote a story for the Phoenix about Opening Day at Fenway Park. He sat in the now-fashionable bleachers, no longer the intimate place he’d known in the early Sixties. When George returned to his seat from a beer run, “The guy who’d been keeping my scorecard wanted to know what the funny little illegibly-scrawled notes in the margin were all about,” he wrote. “I briefly considered a number of spectacular fabrications, but finally admitted that I wrote for the Phoenix and planned to do a story of some sort about Opening Day.

“‘Oh, yeah?’ He eyed me strangely. ‘If you’re a sportswriter why the fuck are you sittin’ here,’ he gestured toward the press box. ‘Instead of up there?’ The fact of the matter was that the Red Sox had declined to provide the paper with press tickets, but for some reason I mumbled that I liked it better in the bleachers. At one time that would’ve been true; today it made me twice a liar.”

By the early eighties, George had moved to the daily Herald American (later just the Herald) to cover sports. He latched onto boxing when Marvin Hagler, who lived in Brockton, Massachusetts, won the middleweight championship. “I jumped on Marvin’s coattails,” George said. Away he went, covering boxing’s last golden age, when Hagler was pitted against Tommy Hearns, Roberto Duran, and his nemesis, Sugar Ray Leonard.

He encouraged younger writers like Pierce and Mike Lupica who went on to become better known than he ever was. The more prestigious Boston Globe passed him over and he never got a call from Sports Illustrated. When Lee wrote a book that went on to become a runaway bestseller, he tapped another collaborator. One reporter who was with George in Boston said, “I always had a feeling that he kind of wanted more to happen.”

“I think the drinking and drug use was exaggerated by some over the years,” George said. “It wasn’t like I was walking around drunk or stoned while I was at the Herald. But there are people who know me well, or think they do, who think I spend all kinds of time boozing in saloons to this day, and I haven’t had a drink in almost 20 years.” He quit drinking cold turkey and when someone asked him if he wanted a drink, George would reply, “No, thanks. I’ve had enough.”

“I think that the alcohol is too easy an answer for why George never became the writer that he and his friends thought he should be,” Pierce said. “I look at him and I see a guy raised by a father who was distant and a mother who worshiped him. This left him trying a) to play a game he could never win, and b) playing a game he’d won just by being born. That is a helluva bind, and I think it created in him a dreadful insecurity. Something deeper in him made him coast.”

“If I wanted to leave something more permanent, write things I’d always planned to write, and leave a worthwhile body of work behind, I needed to get off my ass and do it.”

Montville remembers going to the Lion’s Head with George when they were in New York. George introduced him to all of his high-profile friends. “In his heart, George thought he was good as any of them,” Montville said, “and he probably was but he never put it together. Anybody who works at a paper thinks, ‘I’ll get it all together and write the book tomorrow,’ but tomorrow you’re covering the Patriots game, so when you do have free time, you say I’d rather dig a hole on my day off than write. As a working newspaper reporter it’s hard to get that focus.”

George picked up golf and played with an enthusiasm that bordered on obsession. It was on the golf course that he could spend time with his father, who was diagnosed with lymphoma in the early eighties. The old man had never made general, and George was bothered by the possibility that his arrests and his FBI file had derailed his father’s career. It wasn’t just his politics. It was the porn novel; it was the expulsion from school; it was the arrest; it was the eye he lost in a fight.

His father was given less than a year to live and lasted two. He visited George at spring training where he was introduced to Johnny Pesky and Dom DiMaggio. They even played golf with the old Red Sox stars. Mostly, though, it was father and son: no heart-to-heart confessions, no pat sentimentality, just peace.

Benn Schulberg paced on the worn carpet in George’s living room. The Final Four was on TV, and Benn, the youngest son of George’s late and much-loved boxing pal, writer Budd Schulberg, had money on a game and his team was losing. It was spring 2011. George lay on the couch, a blanket covering his legs. He’d recently returned from Lawrence, where he had visited old friends and did three book signings to promote two boxing anthologies: At The Fights and Manly Art. It had been five-and-a-half years since doctors had given him six months to live. George hadn’t wasted his time. Four books carrying his name had been published since 2009, an atonement for a career of half measures and disappointments.

“It was as if I woke up one morning and realized that however good or bad it might have been, well over 95 percent of what I’d written in my life had been used to wrap fish,” George told me. “If I wanted to leave something more permanent, write things I’d always planned to write, and leave a worthwhile body of work behind, I needed to get off my ass and do it.”

George lit a Lucky and studied the Final Four on TV. His gaunt face was covered with a choppy gray beard; his clothes hung loosely off his emaciated frame. He didn’t talk much, not because his throat hurt but because it was his nature. “He’s more intimate as a writer than he is in person now,” his brother Rocky wrote in an email. “George builds relationships by being side by side with people, at a barstool or at the fights.” When George did say something, he spoke in bullet points about poor shooting and rebounding, about not selling enough books at a recent signing.

At halftime, he went upstairs to feed himself through a tube. Schulberg watched him go. “I knew George from the fights that my dad took me to as a kid,” he said. “George had such a big gut, he’d knock over everything as he moved down the press row. When dad died, George had me over all the time. He wanted to make sure I was OK and looked after.”

And now Schulberg, whom Marge called the Saintly Benn Schulberg, was returning the favor. His father was dead, and there were sad reports coming in from George’s old friends. Pete Hamill told George, “Now they’re shooting at our regiment.”

George returned from upstairs. Schulberg had gone to the store on an errand, and now it was just George and me. He looked at the TV, and I asked him if he was afraid to die. “No,” he said in a soft voice that I hadn’t heard from him before. He looked at the ceiling and said that he was preoccupied with the idea of not being there to provide for Marge and his kids. “I worry about things that won’t get done.”

George filed hundreds of stories after he retired from the Herald, mostly on boxing, for The Irish Times and websites like The Sweet Science. The boxing pieces were collected in Manly Art, and his Irish Times work was published as American at Large. They are the work of a historian as raconteur, an insider, written in an easy, conversational style.

“He’d be the first to tell you he made his share of mistakes in the sixty-four years he’d spent on this earth,” George wrote about Vin Vecchione, “but rescuing Peter McNeeley that night in Vegas wasn’t one of them.”

Vecchione threw in the white towel on McNeeley’s behalf 89 seconds into a 1995 fight against Mike Tyson, saving him from a sure beating. Customers who shelled out fifty bucks to see the fight on pay-per-view were furious, but George thought Vecchione deserved to be named manager of the year; after all, McNeeley collected almost $10,000 per second for his effort.

“Vinnie was a boxing guy through and through,” George wrote, “a Runyonesque character who looked as if he’d modeled his image on that of Joe Palooka’s manager, Knobby Walsh. It was as if he’d been born in that white cap he wore into the ring when he saved McNeeley, and for all I know he slept in it too; I don’t think I ever saw him without it. The other constant was the stubby remains of a cigar he kept clenched between his teeth. You never saw him light up a new cigar, and I always wondered whether Vinnie had found a good deal somewhere on half-smoked stogies.”

George also co-wrote a book with Eamonn Coghlin, the Irish miler, and co-edited a compilation of boxing poetry, The Fighter Still Remains. The Four Kings, the story of Hagler, Hearns, Duran, and Leonard, however, is perhaps his finest work.

“Four Kings was George’s last best shot at a great book,” said John Schulian, a sports columnist and screenwriter. “Some of us think it is great, others think it is very good. Either way, in these lean times for the sport, there are precious few books about boxing that deserve anything close to legitimate praise of that magnitude. It was as honest and heartfelt as a book can be. And smart, too, in the way George at his best was smart—incisive, irreverent, unyielding.”

George had covered all nine fights between the fighters. “I do feel fortunate to have staked a claim to the subject matter,” George said in an interview with British sports writer James Lawton. “I’d love to see Four Kings take its place in the pantheon of sports literature.” Then George remembered what a sports editor once said to a sports writer after the writer had won an award. “Well, that certainly makes you a tall midget.”

It was At The Fights, which he co-edited with his old pal Schulian, that cemented his legacy. A compilation of great American boxing reporting and commentary, it was published by The Library of America, “that distinguished arbiter of durable literature,” according to The New York Times. For George it was a merging of his own literary aspirations and his great affection for, and pride in, the writers whose world he shared and understood.

“When you start defining yourself as a ‘cancer victim,’ you start thinking like a victim, and that in no sense defines who I am or what I do.”

“Trying to do justice to a great 12-round fight when you’ve got 28 minutes to make an edition is the most excruciating exercise imaginable,” George said in an interview on the Library of America’s website. “You just get it done and send it and hope it comes out in English. Of course the real test comes when you have to write a deadline story about a stinking fight. I remember the old AP fight scribe Eddie Schuyler sending his [story] after [one of those stinkers] and turning to me to sigh, ‘If they want me to write better, they’re just going to have to fight better.’”

With At The Fights, George had found a way to make all those nights, all those deadlines, all those seemingly ephemeral pieces take on a kind of permanence and purpose. Here was a chance to show that he belonged in the same collection as Mencken, Liebling, and Mailer. He wasn’t leaving it for fate or history to decide. He would anthologize himself. He would help select America’s finest boxing writing, and he would put himself in there, too, alongside Hamill and Schulberg and W.C. Heinz. If he wasn’t going to be elected to a hall of fame, well, fuck it—he would build one himself, right over his head.

Nobody was sure if George would live long enough to attend the publication party for At The Fights. His friends didn’t know if they’d be celebrating with George or eulogizing him. “He was self-destructive,” said Rocky, “but he’s a hard one to kill.”

The party was held in a large banquet room on the eleventh floor of the New York Athletic Club, and unlike most parties hosted by the Library of America, more than 150 people crowded the room—Gay Talese, Larry Merchant, Jeremy Schaap, Schulian, in from L.A., George’s mother and most of his siblings. Friends from the Lion’s Head and Lawrence, friends from the fights.

George and Schulian made short, earnest speeches, then let Robert Lipsyte and Schaap do the crowd-pleasing. George signed copies of the book with his ninety-year-old mother sitting next to him. Jenny Kimball, standing nearby, admired her big brother’s newfound discipline. For most of her life she saw him having a good time, working hard on his column but rarely pushing beyond that. “What he did these last years,” she said, “he had that capability all of his life.”

The morning after the party, George was back in front of his computer. “Writers write,” he said. “It’s who I am and what I do. It’s really only been the last month or two that I’ve felt truly debilitated, and mostly tired. I haven’t tried to make a secret of it but I haven’t written about my illness and have rejected several invitations to do so. When you start defining yourself as a ‘cancer victim,’ you start thinking like a victim, and that in no sense defines who I am or what I do.

“Even after he’d had his larynx removed, Damon Runyon continued to work and write, communicated by notes—he carried a notepad that said ‘Damon Runyon says’—so he certainly wasn’t trying to hide his illness, but he never wrote about it and when he died most people in New York were actually surprised to learn he’d had cancer at all. My kind of guy.”

“George was always looking ahead to the next project,” Schulian said. “He couldn’t have stopped if he wanted to. As long as he was working, he was alive.” A line from George’s Paris Review poem comes to mind: “[T]here is no rest for the other living. Too much real in the light of day.”

Three days before George died, on July 6, 2011, he wrote a story for the Herald in which he fondly remembered two old friends, a reporter and a boxer who had died of cancer. He didn’t mention that it was also killing him.

[Featured Illustration: Jim Cooke]