The greatest stretch in New York sports came in 1969–In 70. It started when the upstart Jets won the Super Bowl, continued that fall when the previously hapless Mets won the World Series, and was capped off the following summer when the Knicks won the NBA title.

New York in this brief period has been duly celebrated—especially because the town has not seen a winning streak like it since. Yet one chronicler of those glory days is but a distant memory, even to devotees of great sportswriting.

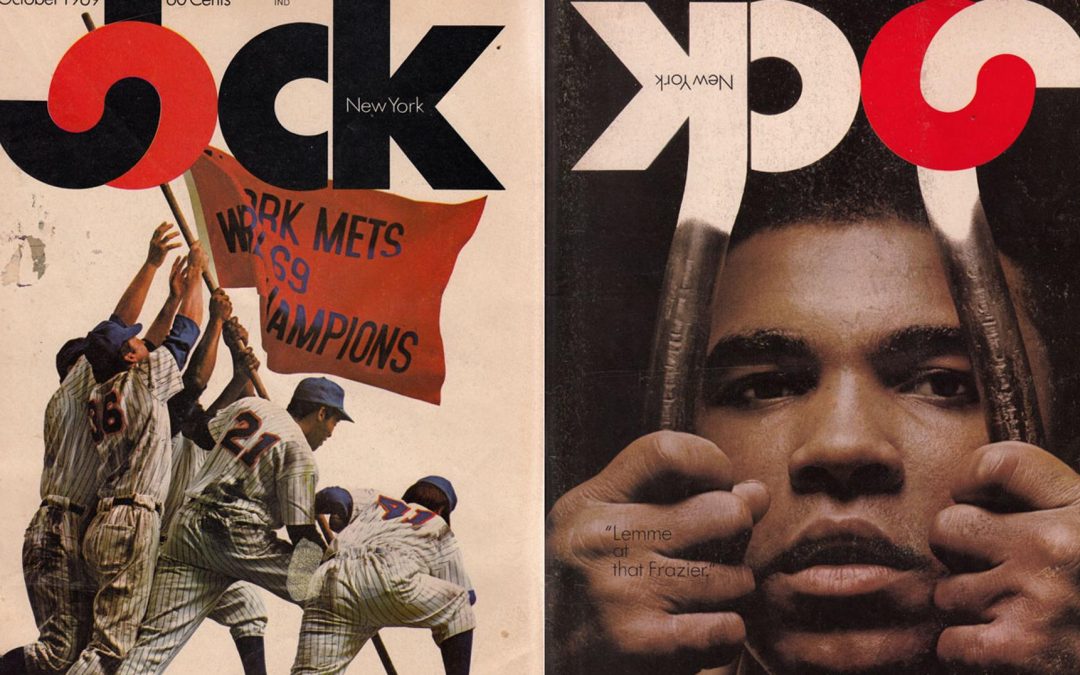

If Jock magazine is remembered at all, it is for the cover of its first issue that shows a group of Mets players raising the flag on the pitcher’s mound at Shea Stadium, a riff on the famous Iwo Jima picture. It goes for a nice sum on eBay, but there was more to Jock than one cover. While the magazine lasted a mere eight issues, it featured the work of Red Smith, Pete Hamill, Roger Kahn, William F. Buckley, and Woody Allen.

It was run by Mickey Herskowitz, a native of Houston, Texas.

Herskowitz was a generation younger than the great Texas sportswriters like Blackie Sherrod, Dan Jenkins, and Bud Shrake. But he was a highly admired columnist for the Houston Post, best known for this opening: “We never knew how important religion was in Texas until people started comparing it to high school football.”

In addition to his column, Herskowitz was the editor for a short-lived monthly magazine called Sports Folio. That led to another monthly that didn’t last long, Chris Schenkel’s Sports Scene, which in turn brought him to New York to run Jock. I recently had the opportunity to talk with Herskowitz, who still lives in Texas, about the magazine and what it was like to be on hand for New York’s sporting season for the ages.

Alex Belth: What was your model for Sports Scene and then Jock? They were monthlies, not weekly magazines like Sports Illustrated. Were you competing with Sport?

Mickey Herskowitz: I wanted them to be more like Esquire. Sports Scene was, in my mind, a success because it was really classy. The people who owned it put a lot of money into it. It was glossy. We could go anywhere and write about anything. I covered the Olympics for that magazine in ’68. And what happened was an advertising guy in New York saw Sports Scene.

Keep in mind New York magazine had just made a big splash and was a big success. There may have been city magazines at the time, but they were small. In Houston, you had one that strong-armed ads for dentists and doctors and lawyers. Had little fashion stories, luncheons.

Alex: They were provincial.

Mickey: Right. They were not for reading. They were beautiful and glossy but no content. New York was the first real city magazine, unless I’m overlooking something in Boston or Philadelphia. So this advertising guy saw Sport Scene and compared it to New York, which was showing a profit after three years, which, if you know magazines, is rare… hell, you are lucky to still be in business after three years. The stock market had had a real go-go run from about ’66–’68, and he thought he could take the model of Sport Folio and Sport Scene and get a Wall Street company to back it. And that’s exactly what we did.

Alex: What was his name?

Mickey: Stan Karp. He had worked briefly for the AFL right before the merger with the NFL.

Alex: Did you move to New York?

Mickey: I did. Had an apartment in the same building with the mayor, though he didn’t live there. John Lindsay played tennis with Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg outside my window on Sundays. I was at Sutton Place. Cost me about $295 a month to park my car, and a luxury apartment in Houston at the time cost about $350.

“The night the Mets clinched the pennant in September 1969 was the night Jock launched.”

Alex: Did the deal happen quickly?

Mickey: I flew to New York and met with their key sales people. It was like Alice in Wonderland. I’m almost embarrassed. It was so easy because so many people love sports. The only people they invited to the business meeting were the ones that were nuts about sports. Why wouldn’t they want to take this company public? I called coach Paul “Bear” Bryant, Jimmy Demaret, A.J. Foyt, Howard Cosell, Curt Gowdy—that was my role.

Alex: You wanted them to invest in the magazine?

Mickey: No, no, they agreed to be on the board of directors and each got 10,000 shares. They did it as a favor; nobody asked for anything. But it was a marquee lineup. We went public in June of 1969, just as the recession began.

In July, the Mets were nine games out of first place. I came up with the idea for the first cover. It would be four or five Mets players raising the flag on Iwo Jima, except it was on the pitcher’s mound. That was on the inaugural issue—must be worth a pretty penny today. Cleon Jones, Tom Seaver, Ed Kranepool, and those guys.

Alex: So you went public near the end of the June and your first issue came out at the end of September.

Mickey: The night the Mets clinched the pennant in September 1969 was the night Jock launched.

Alex: Jeez, talk about good fortune.

Mickey: Talk about phone calls. Every newsstand dealer, and I’m talking about the guys who work under those little aluminum sheds, they were on the phone wondering where they could get more magazines. People were buying them 20 at a time. This is one of the places we went wrong.

Alex: How so?

Mickey: I was a 50-50 partner with Stan, and I begged him to print another 50,000 copies of the first issue. He said, “No, one of the keys of advertising is to leave them hungry.” I said, “Yeah, but in this case, every magazine we print now costs us 20 cents when before it cost a buck and a nickel. Now, we can make money. Plus, every magazine we sell has a subscription card in it. If anyone is ever going to subscribe, it’s going to be this issue.” Well, I didn’t win it. He said by the time we got the magazines out in a week’s time, it would have all cooled off. I said, “Why would it cool off, they’re going to the World Series?”

Alex: They couldn’t have been any hotter, especially since it was the Mets, the lovable losers.

Mickey: It was one of the worst business decisions we could have made. That first printing was 60,000, and we sold 59,100. The guy who was our circulation manager had worked for the Saturday Evening Post, and he told me that was the first true sellout he’d ever heard of in magazine history. He told me that you lose 800–900 copies just because they get torn in the packaging and unloading or people steal ’em. A sellout, he told me, is anything within 10,000 copies of what you print.

We immediately had that cover turned into T-shirts and posters, and we sold a ton of those. I still have the poster in a frame in my living room.

Alex: So, although you didn’t capitalize on a second printing of the first issue, you were still optimistic that you were in the right place at the right time.

Mickey: We thought we’d hit a grand slam. The sales of the magazine kept going up. The lowest sales was that first issue, and that’s because we only had 60,000. It began to sell outside of New York. And we had plans to sell it in Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago. We planned to do editions in the Midwest and the Pacific Coast.

Alex: You had Jerry Izenberg and Stan Isaacs, who were New York guys. But you also had Pete Hamill, Red Smith, and Roger Kahn. The fighter Jose Torres. Murray Chass did a story on Neil Simon. Bill Conlin later did a great piece on Dick Allen. How did you recruit all these guys?

Mickey: Just picked up the phone and asked. They liked the idea of the magazine, so I just let them go. Let them pick a topic and write whatever they want.

Alex: I love “The Odd Couple” segment.

Mickey: I came up with an idea of an interview feature that would be called “The Odd Couple.” I had Bill Bradley and Calvin Hill interview each other, Gordie Howe and Tiny Tim interview each other. Tiny Tim was a hockey fanatic. He thought when he died he’d go to Gordie Howe. Now, we’d come up with the questions for each guy and give it to them, and they’d talk on the phone, we’d record it and then edit it, and that would be the feature.

Bradley came to the office, and when I handed him the questions he did a double-take and sheepishly said, “Do you mind if I ask my own questions? I’ve been thinking about it, and there are some things I’d really like to ask Calvin about.” I said, “Gee whiz, I’d be thrilled.” I just wasn’t used to jocks doing their own interview. Calvin had gone to Yale and Bradley had been to Princeton, and they had a real, adult conversation. It was wonderful.

Alex: I like the non-sportswriting celebrities you featured in the magazine, like William F. Buckley and Woody Allen.

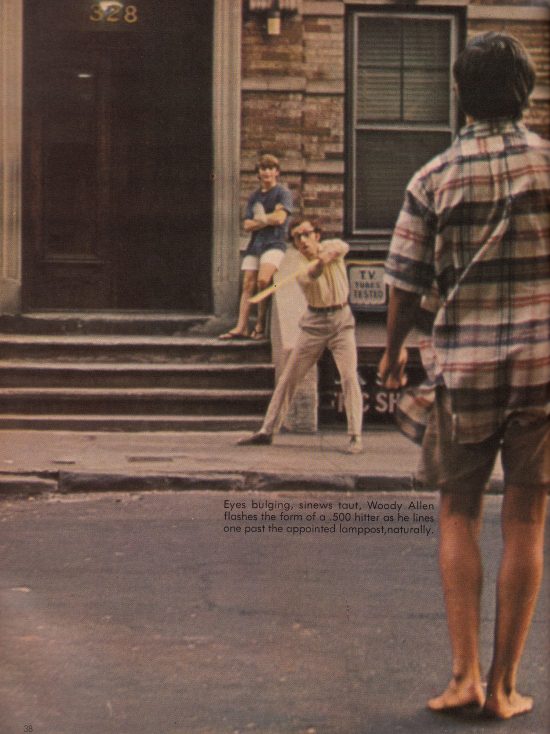

Mickey: I called Woody Allen’s agent, Jack Rollins and Charles Joffe. I don’t know whether I talked to Rollins or Joffe. I told him I was running a magazine called Jock and wanted to know if Woody would be available to write a piece about what it was like growing up playing stickball in New York. He said, “I doubt it, but I promise you I’ll mention it to him.” An hour later I got a call from Rollins or Joffe, and he said, “Yeah, Woody would love to do it. He’s doing a play, Play it Again, Sam, and does two shows on Sunday. Come between the matinee and the evening performance, bring a photographer, and you can get your story and your pictures.”

Alex: So it was ghostwritten by you?

Mickey: No. I went there and Woody dictated it to me, it wasn’t ghostwritten. And he said, “What are you doing to do for photographs?” I told him I thought we’d just take a couple of shots of him there in his dressing room. “That doesn’t make any sense,” he said, “not if you’re doing a story on stickball. I know a perfect brownstone about four or five blocks away, let’s go down there.” So about six of us walked down past Eighth Avenue to this brownstone. I had two of my kids with me, they were like 10 and 11, and two of their friends, and they were the rest of the teams. Woody had a stick and a ball, one of the kids pitched to him, and the others played in the field. And that’s where we got the pictures.

Alex: All-schoolyard.

Mickey: Now, we did this shoot before the Mets had won the pennant, and after they won I get a call from one of Woody’s managers. He said, “Woody wanted to know if he could ask you a big favor?” I said, “Sure.” “Can you get him four tickets to the World Series?” Honest to God I had to bite my tongue. Are you kidding me? You don’t think that Woody Allen would mean more to the Mets than Mickey Herskowitz from Houston, Texas? For some reason that didn’t occur to him. So I called the Mets PR guy and got him tickets to every home game. Next week I got a handwritten thank-you note from Woody.

Alex: You also had an encounter with Paul Simon, right?

Mickey: I sure did. I was thinking of stories, and it dawned on me that Rollins and Joffe also managed Paul Simon. The Graduate had come out, and the song “Mrs. Robinson” was everywhere. So I called up and asked if they thought Paul would be willing to do a story for me on what it was like growing up as a Yankees fan. And Rollins or Joffe said, “Well, I don’t know. I didn’t think Woody would do a story and he did. We’ll ask Paul.” The next day I’m sitting in my office… the secretary put a call through and the voice said, “Mickey?”

I said, “Yeah.”

“This is Paul.”

“Paul, who?”

“Paul Simon.”

I was stunned that Paul Simon called. I said: “Paul, jeez, terrific of you to call, and call back so quickly. And to call back yourself. Everybody usually goes through three or four layers of gatekeepers, I’m really impressed.” He said, “Well, don’t be. It’s an everyday courtesy.”

He talked about what I had pitched and said, “I think it’s a groovy idea and I’d love to do it.” And so I explained what I wanted, but also said I’d love it if he could talk about the Joe DiMaggio line, which everyone was so touched by. It took everybody back to nostalgia in their lives.

Alex: What did he say about it?

Mickey: He said the line just came to him. He hadn’t had DiMaggio in mind, but his name came to him; he had to have a long enough name to fit the melody. It was funny because he told me that a month or so after the song hit big he was on a TV show with Mickey Mantle and Mantle said, “How come you used DiMaggio’s name in your song and not mine?” Simon said he had to explain to him that it had to do with the melody and not the name.

Alex: That’s funny that Mantle asked him. Because he was also a player of Simon’s generation more than DiMaggio.

Mickey: That’s right. Anyhow, we didn’t talk long, maybe about ten minutes. I was out of things to say. But I was so flattered and grateful for the call, I felt like I had to say something. So I told him that “Mrs. Robinson” was my favorite song. I made it up; it was such a dumb, bullshit thing to say, but I felt I had to say something complimentary to him for calling. There was a pause on the other line. And the next thing he said was, “You didn’t like ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water?’ ” You talk about the insecurity of an artist?

Alex: He was straight, he wasn’t joking?

Mickey: I said, “Oh, no, no, no. ‘Mrs. Robinson’ was my favorite sports song. I love ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters.’ ” And the truth is, I didn’t know what he was talking about. I had been hearing it for weeks but didn’t know the name of it.

Alex: So did Simon write something for you?

Mickey: He did, but it was for the issue that never got published. Isn’t that heartbreaking? And I had that article in the galley proof and saved it to keep along with my memorabilia. Kept it with the Charlie Schulz cartoon and a story that Muhammad Ali did for me and did an original drawing for the magazine, too. And somewhere between moving the stuff from the office back to Houston it all disappeared.

Alex: So even though the magazine was a success critically, you weren’t making money. So after eight issues…

Mickey: Backtracking for a minute. When we started, the underwriters took us public at $5 a share, really a simple deal, 200,000 shares to the public. They raised a million, and after they paid all the commissions we had $750,000 for a budget. Sadly, it cost us $80,000 to print the magazine. We were shortsighted and printed in Brooklyn. Should have gone to Kansas City or some place, but we felt like we had to do everything in New York to give it that New York aura.

So at $80,000 a month it doesn’t take a calculator for you to guess that in seven, eight months we were going to be out of money. Now, the underwriters said, we’ll do a secondary. You don’t have to show a profit, but if the magazine is selling, we’ll do a secondary and raise $2 million to $5 million and you’ll be set. By the time six months passed and we knew we needed money, we had gone into an awful recession, the Nixon recession. And they couldn’t do a thing for us because half of their companies were going broke, including themselves.

Alex: So after eight issues, you were sunk.

Mickey: We were going broke, and it was obvious that we weren’t going to make it. The underwriters tried to find a way to save the company or at least ease it into the grave in a way that didn’t generate a lot of lawsuits.

Actually, they were confident they could find a buyer. This was May or June of 1970. But my partner thought we’d pull something out of our hats. We’d get a loan or figure out a way to keep going. We had a good offer from Weight Watchers. They wanted to buy us and have us share the offices of a new humor magazine they were starting. That magazine turned out to be National Lampoon.

Alex: No way…

Mickey: The plan was that we would share talent between the two magazines. I’d stay editor-in-chief of Jock, and we could have made that deal with Weight Watchers, and we would have been partners with National Lampoon. We would have had their writers writing for us and been involved in their movies. If that had happened, I’d probably be somewhere in the South of France right now.

Alex: So what ended up happening?

Mickey: Every day we had a meeting, and we couldn’t agree on the terms. Finally, we had one offer left with a company called International Leisure Hosts in Phoenix, which was to buy the company for nothing, but Stan and I would get 30,000 shares of whatever they decided to do with it. So that was the deal we made.

I flew to Phoenix, spent a week with the guy who bought the company, and we became great friends. He spent a few months seriously considering reviving the magazine. He was a real estate guy and put his money into things he knew about, and he couldn’t see making money with a magazine. So he shut it down, but we remained friends, and that was the end of Jock magazine.

We ended up practically giving it away. We had $60,000 in the bank. And he sold our subscriber list to Sports Illustrated, and he made $120,000 out of it.

Alex: It didn’t work out in the long run, but it was a nice moment, especially in the history of New York sports.

Mickey: Oh, it was a heck of a magazine, a lot of intellectual people loved it, and I only regret that we never got a chance to do our best work. We didn’t have enough time, and we were under a lot of pressure in the time we did have. We had a small staff, but what we did put out we did well. Everything in it is something I can be proud of.