In five hours Gordie Howe would play hockey with the Detroit Red Wings against the New York Rangers. Now it was 3:30 in the afternoon, and he was sitting at the kitchen table in his new home in a residential suburb fourteen miles northwest of downtown Detroit. He was eating the meal on which he would play—steak, peas, lettuce, fruit jello and tea.

“When we play those Saturday afternoon TV games,” he was saying, “I just play on my breakfast eggs. Once, when I was with Omaha, I played on a milkshake.”

There is a radio built into one of the kitchen walls. It is the center of a communications system that reaches upstairs to the three bedrooms and downstairs to the oak-panelled recreation room, and now the voice of Perry Como was coming over it.

“Don’t let the moon get in your eyes,” Como was singing. “Don’t let—”

“I was 17 years old,” Howe said, “and it was our first swing around the league. We were in Minneapolis, and about 4:30 I went downstairs in the hotel to eat. Some of the guys were eating there, but I looked at that big dining room and it looked so nice that I didn’t want to go in. I went around the corner to a drug store and I had the milkshake.”

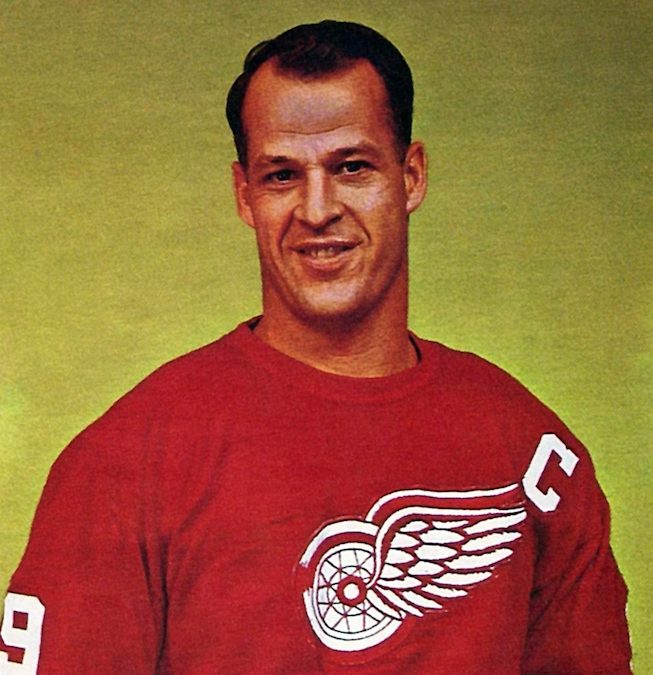

He is six feet and 201 pounds and has brown hair that is beginning to recede at the temples. His face has been cut by pucks and sticks more times than he remembers, but the only scar that is obvious is in the form of a small crescent on his left cheek bone.

“Don’t you still sometimes feel that way,” he said, “when you start to go into a dining room or a restaurant that looks extra nice?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I got two goals on that milkshake,” he said, “and we beat them 3 to 1.”

Gordie Howe will be 31 on March 31, and many observers maintain he is the greatest hockey player of all time. Jack Adam, the general manager of the Red Wings, and Muzz Patrick, who holds the same position with the Rangers, have called him that, and certainly he is the best in the game today. Six times he has been named to the All-Star team. Last year, for the fourth time, he was voted Most Valuable Player in the league, tying the record set twenty years ago by Eddie Shore of the Boston Bruins.

“Back home when we’d skate,” he was saying, “we’d have our oatmeal in the morning. That would last you practically all day, if you didn’t want to take time out to eat.”

All of those who play in the National Hockey League come up the same way, and only the names and the places and the dates are different. This one was born in Floral, Saskatchewan, on the outskirts of Saskatoon, in the heart of Western Canada’s wheat prairies. He was the fifth of nine children. His father, Ab, tried farming and then moved the family into Saskatoon where he ran a garage and is now a maintenance superintendent for the city.

“After breakfast,” he said now, “we’d put on our skates at home and skate down the ruts in the road to the rink. If we came home for lunch my mother would have newspapers down on the floor in the kitchen so we could keep our skates on. Sometimes there’d be a whole flock of guys, and she’d give us a stew or a thick soup. We’d do that again for supper, if we were gonna skate again at night.”

“Do you remember,” I said, “the first time you were ever on skates?”

“My brother Vern had a pair,” he said. “He’s about eight years older than I am, and he was about 13 at the time. My sister Edna took one skate and I took the other, and I was so small that I put I it on right over my shoe. We went out on the rink in the yard and pushed around on one foot. That was the first time.”

“You had a rink in your own yard?”

“It would be so cold that, if you stuck your head out of the door at night you could hear a guy walking two blocks away.”

“A lot of people did. The first few snowfalls you’d build up your banks, and then when the snow melts it runs off the banks and freezes. Every school and playground had a rink, too. There were rinks all over town. Then when the warm wind—the Chinook—would come, the water would run into the low areas, too, like the Bay Slew, and we’d skate for about seven miles. We’d skate and walk over the Mile Road and skate and walk over the railroad and skate some more. We’d skate four or five miles up the Saskatchewan River, and play a game between the piers of the Grand Trunk.”

“How cold would it get?”

“I guess the coldest would be 50-below. A lot of times it would be 25-below. It would be so cold that, if you stuck your head out of the door at night you could hear a guy walking two blocks away. You know? When I played goalie I remember I used to skate a mile from my house to the rink, holding the pads up in front of me to cut the wind. At the Avenue F rink they had a heated shack, and a guy would ring a cowbell and the forward lines and the defense for both team would go off and sit in the shack by the pot-bellied stove. After awhile he’d ring the bell again and the other guys would come in and somebody’d say: ‘Who’s winnin’?’”

“Didn’t you ever freeze your face or your feet or your hands?”

“Sure, but you’d put snow on it. You’d put a scarf across your nose and mouth and when you breathed through it, it would get all white with frost. You’d take a stocking and cut a hole for your eyes and wear it over your head. A lot of kids froze their toes and used to cry.”

“How old were you when you got the first pair of skates of your own?”

“I was about 5 and we were on relief at the time. A woman came to the door one night with a whole potato sack full of things, and my mother paid her a dollar and a quarter for it. I remember diving into that bag, and there were four or five old pairs of skates in there and I grabbed a pair. They were so big I had to wear a couple of pairs of extra socks.”

As he had been telling this there had come a knock on the door leading to the garage. His wife, Colleen, had been rinsing plates at the sink and putting them in the dish washer. Now she dried her hands and went to the door.

“Is Gordie Howe home now?” a small voice said.

“Yes,” his wife said, “but he’s eating.”

“Oh,” the voice said.

“Did you boys want to ask him some questions?” his wife said.

“Yes,” the voice said.

“You can come in,” she said.

They walked in, three boys about 10 years old. They stood awkwardly, looking at him and then looking around the kitchen.

“Hi, fellas,” Howe said.

“Hello,” they said staring at him now.

“What are your names?” Howe said.

“Mine’s Bill Little,” one of them said, “and this is Chuck Watson and his is Miles.”

“Do you boys know any babysitters?” Mrs. Howe said.

“Oh, sure,” one of them said. “My sister sits, and so does his. They’d like to sit for you.”

The Howe’s have two sons, Marty, who will be 5 in February and Mark, who will be 4 in May. They had come up from playing downstairs when they had heard the strange voices, and now they were eying the older boys.

“I don’t want no sitter,” Mark said.

“Sure you do,” Howe said.

“No I don’t.”

Mrs. Howe had written down the names and phone numbers of the sisters of the boys. Now the boys were just standing at the end of the table and watching Howe finish his dessert.

“Do you fellas have a rink around here?” Howe said.

“Nope,” one said, “but my Dad and Mr. Cranbrook were thinkin’ to put one up.”

“I don’t want no sitter,” Mark said.

“We have to go now,” another said. “Thanks a lot.”

“It was nice to meet you fellas,” Howe said.

They walked to the door, took a last look at him and then went out. Mrs. Howe closed the door behind them.

“They were here yesterday,” she said, “and they said they wanted to ask Gordie some questions. Then they come in and they’re afraid to ask anything.”

“It’ll wear off,” Howe said. “When we first moved into the other district you never saw so many kids in your life, but they get used to you.”

“Remember,” a voice on the radio was saying, “you can hear the game between the Detroit Red Wings and the New York Rangers over WXYZ tonight at 8:30.”

“Did you have hockey heroes when you were a kid?” I said.

“Ab Welsh, who was a forward with the Saskatoon Quakers was the first one,” Howe said. “I used to hang around the Arena and watch them practice, and he’d give me a stick that had lost its life, that was a little loggy. He used a Number 7 lie, and I still use a Number 7 lie today. Once, on the last day of the season, a red-headed defense man for the Flin Flon Bombers gave me his old elbow pads.”

“Who were your idols in the National Hockey League?”

“When I played Pee Wee hockey they called our team the Red Wings. They’d give you a stick and your socks and a sweater, and the name and number of a Detroit player. I was Sid Howe, so I wrote him for an autographed picture. Later, when I came up to the Red Wings, he was still here, and Jack Adams asked me my name and I said: ‘Howe, but I’m not related to him.’”

“Marty!” his wife was saying now. “Get out of there!”

That day she had bought three plastic waste baskets for the new home and they were standing on the kitchen floor. The boy had his head and upper body submerged in the largest one, as he tried to reach something at the bottom.

“What?” he said, straightening. “Why?”

“The first time I remember hearing Gordie’s name,” his wife was saying, clearing the table, “was when he was almost killed in that game here and they had to drill into his head to relieve the pressure on the brain.”

“He gets that from me,” Howe said. “When I was a kid, if you sent a Bee Hive Corn Syrup label to Toronto you’d get a picture of a hockey player. All of us kids would be up and down the alleys looking in the ash cans for the labels. I was the champion. I had about a hundred pictures.

“I had this note book. I remember it had ‘Scrap Book’ printed across the cover on a slant. It starts out thin, and by the time you get all the hockey pictures and autographs and everything in, it’s bustin’ the seams.”

He looked at his watch. It was 3:55 and he went upstairs and got into his pajamas and lay down and slept for two hours.

“The first time I remember hearing Gordie’s name,” his wife was saying, clearing the table, “was when he was almost killed in that game here and they had to drill into his head to relieve the pressure on the brain.”

That was in the Stanley Cup playoffs in 1950. Ted Kennedy, of the Toronto Maple Leafs, had checked Howe, and he had gone down in a heap against the boards in front of the Red Wings bench. They had carried him, unconscious, off the ice to an ambulance at the back door of the Detroit Olympics, and from there to Harper Hospital where Dr. Frederic Schreiber had saved his life.

“Carl!” he had been calling, as he came out of it, calling for Carl Mattson, who was the Red Wing trainer. “Help me, Carl!”

“I didn’t know anything about hockey,” his wife was saying, “and I’d never heard of Gordie Howe. I was in my senior year in high school here, and that morning after he was hurt, when I came down to breakfast, my Dad was storming around. He was a Red Wings fan and he was mad. Of course, I didn’t know then that Gordie Howe was the man I was going to many three years later.”

They met the following year at Joe Evans’ Lucky Strike Alleys on Grand River, across from Northwestern High School and three blocks from the Olympia. She was bowling in a league, and Howe was there with Vic Stasiuk, who was a left wing with Detroit then, but is now with the Boston Bruins.

“How did you like meeting a celebrity?” Joe Evans, who introduced them, asked her a few minutes later.

“Is that a celebrity?” she said.

“Are you kidding?” he said. “That’s Gordie Howe of the Red Wings.”

They were married at 4 P.M. on April 15, 1953, in the Calvary Presbyterian Church on Grand River. Ted Lindsay, Reggie Sinclair and Marty Pavelich, of the Red Wings, were ushers, and Ted’s wife, Pat, was matron of honor. Since then Colleen Howe hasn’t missed more than four or five home games.

“I get excited,” she said, “but you have to learn to bite your lips.”

“Are you ever nervous,” I said “about Gordie being injured?”

In 1946, his first season in the league, he lost his upper two teeth in Toronto. Against Montreal at Detroit a stick drove his left lateral incisor and cuspid up into his gum and, although Dr. Florian Muske, the team dentist, pulled them down right after the game they are still a little higher than the rest.

He has had operations on both knees, and they had to put him under anesthesia to clean a long gash in his left thigh. Six years ago he played fifteen games with his broken right wrist in a cast, and led the league in goals and assists while setting an all-time season record of ninety-five points. Last year his left shoulder was dislocated, and a week later he was hospitalized for ten days with torn rib cartilages.

His nose has been broken several times, and the skin over the bridge has been sewed so often that it is now difficult to get a needle through it. Like most professional hockey players, however, he is unable to tell you how many stitches have been taken in his face or to recall when or how the cuts resulted. He remembers that one cut under his lower lip had to be reopened, because of a bad sewing job, and that the one on his left cheek bone pained him because they wired it.

“Never,” his wife said, “do I go to a game thinking that Gordie might be hurt. Sometimes, when he’s already playing with an injury, and I can see somebody on the other team getting mad and banging around, I hope they get him off the ice before he does hit Gordie.

“What you think about more is whether he’s getting his goals and assists and whether the team is winning. If he goes five or six games without a goal it begins to bother him. He doesn’t say anything, but he gets very quiet. I save up the crossword puzzles for him, because at a time like that he likes to work them to take his mind off it.”

When he came downstairs at 6:20 he had shaved and he was wearing a brown suit, white shirt and brown tie and carrying a brown topcoat over his left arm. The cleaning woman, who comes out from Detroit on Thursdays, was standing in the kitchen with her coat and hat on.

“They tell me the buses don’t run here after 4:30,” Colleen said to him. “Can you drop Bea off on your way?”

“Sure,” he said.

“I don’t want to be any trouble,” the woman said.

“I wanna go, too,” Mark said.

“They’re going to pick me up about 7,” his wife said. “I’ll wait for you afterwards.”

“I wanna go, too,” Mark said.

The blue and white station wagon was in the driveway, and when he got in behind the wheel Mark was still with him. He was standing so that his father could not close the door.

“I don’t want you to go,” he was saying.

“Your Daddy has to go,” the cleaning woman said from the back seat.

“Why?” the boy said.

“He has to play hockey,” she said.

“Here,” the boy said, holding something out to his father. It was a yo-yo.

“You give that to Mommy,” Howe said.

“Why?”

“I think Mommy might want to play with it.”

As he drove through the headlight-broken darkness now, other cars passed him bringing other men home from other jobs. This started with him when he was 15, and sat in the parlor of the two-story shingled house on Avenue L North in Saskatoon and listened while Russ McCrorry, the Rangers scout, talked to his mother and father.

One night late that Summer they put him aboard the sleeper for Winnepeg, and when he got off he asked for the Marlborough Hotel. He roomed there with another kid, a goalie, and all they did was walk to the old Ampitheater for practice and back again. Only once did he stray far enough to buy his mother a pillow case with “Winnepeg” on it.

After three days they let the goalie go. Two days later, when Lester Patrick and Frank Boucher called him up to their room to sign him, he just shook his head. He wanted to go home.

A couple of years ago he was signing autographs for three hours in Fort William. One of the men in the line asked him if he remembered him. He had been that kid goalie at Winnipeg.

“And now the Kingston Trio,” the voice was saying on the car radio, “and the sad story of ‘Tom Dooley’.”

The next year he sat in the living room and listened again while Fred Pinckney, the Detroit scout, talked. The Red Wings practiced in the Windsor Arena that August and September, and Jack Adams signed him to a Galt contract.

At 16 he was too young to play, but he practiced with the team and played exhibitions. They enrolled him in the high school, but when he got near that big brick building that first day and saw all the kids outside he walked down the railroad track instead and got a job as a spot welder with Galt Metal Industries.

“This is the street, isn’t it?” he said now, to the woman in the back seat.

“That’s right,” she said. “You let me off right here by the corner, and thank you and good luck tonight.

“Thanks,” he said.

He left the car at a gas station a block from the Olympia. and it was 6:55 when he walked into the dressing room. Gus Mortson, the defense man who played for Toronto and Chicago before he was traded to Detroit last September; Terry Sawchuck, the goalie, and Len Lunde and Charlie Burns, the rookie forwards, were already there. Howe walked through to the trainer’s room in the back and took off his topcoat and his jacket and hung them up.

He has the slope-shoulders they look for in a prizefighter, and the strong but loose wrists that the power hitter brings to baseball. His body is long-muscled, except that the years of skating have built up his thighs.

“How do you feel?” Sid Abel, the coach, said to him.

Twenty-one years ago, when Abel played center for the Flin Flon Bombers, Howe was the kid who used to carry their skates into the Saskatoon Arena. Nine years later he joined Abel on one of the Red Wing forward lines.

“All right,” he said, “but a little tired.”

“When he says that,” Lefty Wilson, the trainer, said, “he’s liable to get three goals.”

“I’d like that all right,” Howe said.

He got a deck of cards and straddled one of the rubbing tables. He started to shuffle the cards and Mortson pulled up a chair. It was his elbow that took out Howe’s teeth that night in Toronto. Several weeks later it was Howe’s stick that broke Mortson’s nose, and last year it was Mortson’s body check that put Howe into the hospital. Now they played gin rummy for about twenty minutes.

“That’s enough for me,” Howe said, finally.

Before he started to undress he took the bridge out of his mouth and wrapped it in his handkerchief and put it in a pocket of his jacket. He walked out to where some of the pieces of his uniform were spread on the bench, the rest hanging from a hook on the wall, and he stripped.

He has the slope-shoulders they look for in a prizefighter, and the strong but loose wrists that the power hitter brings to baseball. His body is long-muscled, except that the years of skating have built up his thighs, and now he got into the long underwear and then the white woolen socks. He pulled on the long red and white stockings and rolled them down to the ankles. He stood up and fastened on the garter belt, and then sat down and fitted the right shin pad and pulled the stocking up over it and fastened the top of it to the garter. He did the same on the left leg, and then he stepped into the red pants.

It was quiet in the room, the players, all dressing now, serious and saying little and keeping their voices down. Overhead, the circular hot air blower made a whirring sound, and Howe walked over to the stick rack in the passageway leading to the showers. He looked at the half dozen sticks with his name and his number—9—printed on them. He selected one and examined the tape on the blade.

Last season he broke more than 100 sticks, and he tried this one, putting some weight on it. Then he got the finger nails of his right hand under the black tape near the heel and ripped it forward. He made a ball of the old tape and tossed it underhand at Norm Ullman, who centers the line with Howe on the right wing and Alex Delvecchio on the left. He went to the tape well in the table near the center of the floor and took out a new roll and sat down at his place and re-taped the blade, starting about two inches from the heel and working forward.

When he had finished he found a piece of absorbent cotton on the bench, and he rubbed the tape blade with it, some of the fuzz adhering to the tape. Then he took the roll and, to hold his shin pads steady, he taped bands above both ankles and just below both knees. Next be laced on first the right skate, with a pad of cotton under the tongue, and then the left.

“People here in the States who haven’t skated much,” he said once, “alway ask me if our ankles ever hurt. Believe me, I’ve never heard of a hockey player’s ankles hurting.”

“Among other things,” I said, “that mystify Americans about hockey players is your ability to stick-handle and pass, usually without looking at the puck or where you’re going to pass it.”

“If you kept your eyes on the puck,” he said, “you’d end up in the rafters. You take glances at it, but you know it’s there by the feel. What helps you on stick-handling is when you’re a kid you play with a tennis ball. There was a family named Adams in Saskatoon, and they had a rink with boards, between their house and the barn. We’d go all day there with a tennis ball, fifteen guys on a side, and when the ball got frozen we’d go over and knock on the window and the lady would open the window and we’d throw in the frozen ball and she’d throw out another one.

“On passes off the boards you have to get to know how fast the boards are. In Detroit here, the puck comes off the boards real good. Boston is fast, too, but in New York the boards are slow.”

“How much did you work on shooting when you were a kid?”

“When there was no ice,” he said, “I used to shoot in the yard off a piece of cardboard. I knocked so many shingles off the house with the puck that my mother made me stop it.”

Now he put on the shoulder and elbow pads and pulled on the red and white home jersey with the white C on the right front shoulder designating that he is the captain. At 8 o’clock the team filed out to warm up, Sawchuck leading, wide-legged in his goalie pads, and Howe last.

“There’s Gordie! There’s Gordie Howe! Hey, Gordie!”

The fans were lined up, three deep, along the green, rubber-tiled path the players tread from the dressing room to the ramp leading to the ice. One of them who called to him was a girl, round-faced and wearing eye glasses, who appeared to be in her late teens. She had on a blue boy-coat, and to the right lapel was fastened a three-inch red cloth 9, Howe’s number.

“C’mon Gordie,” she called. “Get some goals tonight.”

He brings to hockey the same long-striding, seemingly effortless grace that Joe DiMaggio brought to baseball but each time he came off the ice the sweat was running off his nose and down his cheeks and settling in the creases in his neck.

He started this season with 386 goals and a record 440 assists. In the history of the National Hockey League only Maurice Richard, the great, 37-year-old right wing of the Montreal Canadiens, with 508 goals in sixteen seasons has outscored him. At the end of last season, the six coaches of the National Hockey League, polled by the Toronto Star, selected Richard as having the most accurate shot and as the best man on a breakaway. They named Howe the smartest player, best passer and playmaker and best puck carrier.

Skating onto the ice on this night, however, he had not scored in six games, although he had set up five goals with assists. For most of this game it appeared that he would be shut out again, for although the Red Wings went ahead, 1 to 0, in the first period, and led, 3 to 1, at the end of the second, his chances were few and marked by frustration.

In the third minute of the first period he rode Ed Shack, the Ranger rookie wing, off the puck in front of the New York net, but in doing so he overskated it. In the twelfth minute he knocked a high puck down just inside the Ranger blue line, stick-handled it around John Hanna, the Ranger defense man, shifted Gump Worsley, the Ranger goalie, with a fake to the right and then hit the other post with his shot.

“You have to accept those things,” he said later. “A couple of years ago I had twenty-two posts by Christmas, and I think I still led the league in goals that year.”

In the second minute of the second period his shot off Worsley’s pads hit the post again. Six minutes later he stole the puck from Shack just inside the blue line, laid a pass on Ullman’s stick, took the return fifteen feet out and was tripped by Bill Gadsby.

On the Red Wing power play he took a pass off the boards from Delvecchio, slapped a high shot from the side that Worsley picked out of the air as it was about to go into the upper left corner. At 19:25 of the period Worsley saved on him again, when the puck hit his right arm.

Through all of this, however, Howe was, as he always is, the workhorse of the Red Wings. He plays between thirty-five and forty minutes of every game, and is on the ice not only with his own line but every time the Red Wings, because of penalties, have a one-man advantage or are one man short. He brings to hockey the same long-striding, seemingly effortless grace that Joe DiMaggio brought to baseball but each time he came off the ice the sweat was running off his nose and down his cheeks and settling in the creases in his neck.

Then, at six minutes and forty-seven seconds of the third period, that thing happened for which the Detroit hockey fans wait. Marcel Pronovost, the Red Wing defenseman, passed off the left boards to Tom McCarthy, on the left wing and just outside the Ranger blue line. McCarthy skated three strides across the line and slid a lead pass to Howe. Howe took it, split the two Ranger defensemen, as they attempted to close on him, and then cut to his left to come in straight on Worsley. When Howe was about ten feet out, Worsley came out to meet him. Howe faked the shot to Worsley’s left, and Worsley went down on the ice to that side. Completing the motion, Howe pulled the puck back to his own left and back-handed it hard into the open side of the net.

That was the final score, 4 to 1, and fifteen minutes later, when he took off his uniform in the hot, humid, body-crowded, voice-filled dressing room, his long underwear was gray and heavy with his sweat clung to him. After he had showered he stepped on the scales, and he had lost six and a half pounds.

“You get it back over night,” he said. “It’s just liquid.”

When he had dressed he autographed his way through the crowd outside the dressing room door and he met his wife. They drove out to a restaurant on Eight Mile Road, and he drank two glasses of water, waiting for his roast beef sandwich and tea.

“Once you had Worsley out of position and down,” I said, “you still drilled that puck as if you were trying to fire it through cords.”

“The cardinal sin is to slide it easy,” he said. “In my first year I had Frank Brimsek beat in Boston and I just slid it and he came over with his lumber and got a piece of it. Sid Abel was playing then, and he said: ‘Any time you see that net, drill it.’ I went back and beat Brimsek again and really let it go. I never forgot it.”

“I suppose you remember your first goal in the big league.”

“It was our opening game here against Toronto,” he said, “puck was lying loose ten feet from the net and I just slapped it in.”

“Did you save the puck?”

“I kept it and took it home and gave it to the folks,” he said, “but I have no idea where it is now. The trouble with those things is that they lose their importance.”

He had his right hand to his face and was absent-mindedly rubbing the scar on his left cheek bone. When he realized what he was doing he stopped.

“Rubbing a scar gets to be a habit,” he said. “When you get a new one they tell you to put coco-butter on your fingers and rub it a lot so it won’t show so much.”

“You were saying that things lose their importance,” I said. “What about all the honors you’ve won? Do you derive satisfaction from thinking about them?”

“No,” he said. “You don’t think about what you have, but you’re going to do afterwards.”

His hockey skills have earned him his home and the home he bought for his folks in Saskatoon. He and Al Kaline, the outfielder of the Detroit Tigers, are partners in the Howe-Kaline-Carlin Corporation, an engineering firm in Detroit, and he works at that during the off season.

“A lot of the young ones,” he said, “they think that when they make the club the job is done. That’s just the beginning. All the honors you get, it’s not to achieve honors but to achieve a better living.”

“Excuse me, Mr. Howe,” the waiter said, “but there’s someone at the bar who would like you to autograph this menu.”

This story is collected in The Top of His Game: The Best Sportswriting of W.C. Heinz.

[Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons]