Anywhere, U.S.A.

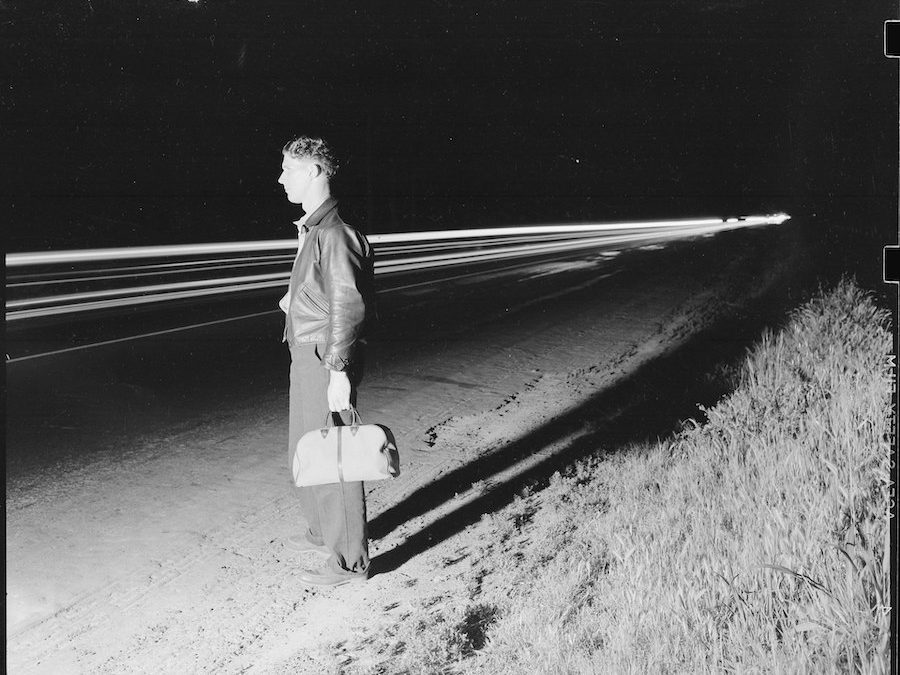

Hitchhiking, thumb up on some dusty road with the diesels honking and the curious kids in the back of the station wagons blinking their eyes, was the only way to go. By Friday, after a week of sneaking beer at the roadside joints and paying for a couple of movies and buying some hamburgers and cigarettes, a college student was flat out of money. The only way to get home for the weekend—home, where Daddy and the bank account were—was to go out on the road and beg. GIVE A STUDENT A LIFT read the sign on the cozy bus shelter at every road leading out of town. There was another reason for hitching, too, although we never discovered it until after the fact. We found out that hitching rides was a good way to get an education. This was not, as Merle Haggard sings in “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am,” the sort of education you get in a classroom. College professors who read from notes they have been using for twenty years cannot tell you how it is Out There. They can tell you that two plus two equals four, but they can’t tell you why. And that is the only thing that really counts. Why?

One time in Arkansas, just west of Memphis, I was stranded on a stark stretch of blacktop for three hours. It was almost impossible during the 1950s to get a ride around there because of the publicity attending the murder of a family by some crazy who stuffed them all in a well after getting a ride from them in their station wagon. Finally, at dawn, a farmer in a pickup truck stopped. I had to ride in the back with two hogs. He stopped about ten miles down the road, in the middle of nowhere, and let me out. An hour later I got a ride with a crazy old woman, about eighty, who had three dozen gallon bottles of “water” in the back of her Model T. It took an hour for us to move ten miles. She stopped at nearly every dirt road leading off the blacktop. She had no teeth, and her hair was bailing out. After every delivery she would return to the Model T stuffing bills into her smock. When it appeared I was getting impatient she invited me to drink some of the water. It was probably the best moonshine whiskey I ever tasted.

Hitching was, then, the most educational experience I ever had. You found out how Real People lived. You encountered drifters and families allegedly off on carefree vacations and bug-eyed truckers and frenetic traveling salesmen. Hitching, even once we had graduated from college and had enough money to buy plane and bus tickets, was a nostalgic trip worth every minute of the effort. It was the “call of the open road.” It was like kissing a girl for the first time. You figured that the stories about hitchhikers being molested—beaten, robbed, raped—by drivers were as overplayed as the stories about airplane crashes. You figured that thousands of hitchhikers were being picked up each day without incident, just as millions of people were flying in planes without crashing, and that the occasional mayhem that took place was happenstance.

All of that, however, was before a certain summer in Missouri. This was around 1955. For two summers I had been playing semipro baseball in southeastern Kansas. The minute college let out in Alabama I would hitchhike the eight hundred or so miles to Kansas, in order to save money (my salary was fifty dollars a week, and I got free room and board), and when the season ended I would hitch back home to Birmingham before the new term began. There had been some moments of trepidation during that period—a homosexual approach at a bus depot in Jonesboro, a terrible accident in Corinth, Mississippi—but in general the plan had worked. I had always got where I needed to get. For free.

It was hot that day, blistering hot, as only Missouri can get in August. This was at the edge of the Ozarks, where there are low, ugly mounds of red dirt. After two hours of beating off the gnats at the split in the road, I saw him coming. I had been there for more than two hours. Coming toward me was a faded-green Terraplane Hudson, which you don’t see anymore (there is, today, a Terraplane society celebrating one of the last of the ugliest American automobiles), but at this point I would take a ride in a Sherman tank.

The driver was a burly man. He hadn’t shaved in two or three days. His hair was mussed. It was so hot he had taken off his shirt. His sleeveless undershirt was soaked with sweat. Ugly black hair covered his arms and his shoulders like a sweater. He drove with his left hand. He kept his right hand on the seat, under the shirt between us. He didn’t say much. I was scared to death.

“Hot, ain’t it?” I said.

“You got that part right,” he said.

“How far you going?”

“Where you want to go?”

“Springfield.”

“Then I’m going to Springfield.”

He kept looking at me without saying anything. He never moved his hand from beneath the shirt on the seat. I made jokes, but he would only smile faintly. He asked me where I was going and where I had been. I told him I had been playing baseball and was going back home to return to college. I told him I loved my mother and I wanted to be a writer if I couldn’t be a baseball player. “Uh-huh,” he said. Then he moved his hand from beneath the shirt and a pistol flashed, and I learned, for the first time, that it works both ways. “I guess you’re all right,” he said. “Put this in the glove compartment, will you?” He even bought my lunch at the next roadside diner. It was the last time I hitchhiked.

[Photo Credit: By Rondal Partridge, Public Domain]