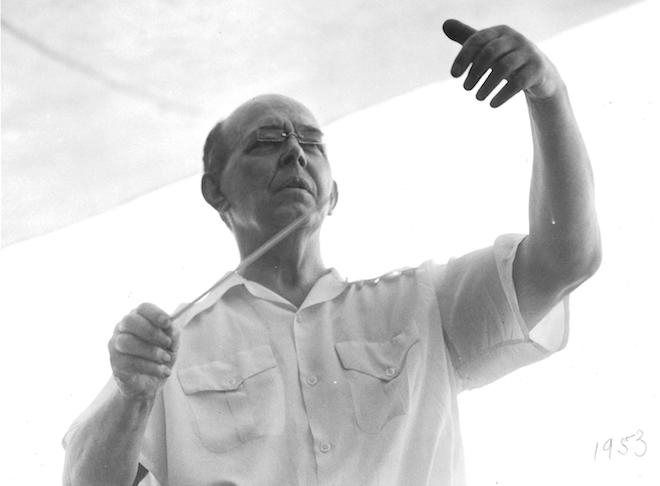

I thought you might appreciate this letter written by Nicolai Malko to Vladimir Nabokov. Here, let Malko’s son, George—a fantastic writer and an equally swell guy—explain:

The letter was written when my father was in his fifth year as Musical Director of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. The letter was written on April 23, 1961, and was sent to Nabokov at Cornell University, where my father believed Nabokov was still teaching.

I don’t know how long it took the letter to get from Australia to Cornell; it couldn’t have been that long. It didn’t really matter. The success of Lolita had already allowed Nabokov to retire from teaching and at the end of 1959 he left Cornell. By early 1961, Nabokov and his wife had settled in Montreux, Switzerland. My father’s letter sat in the Ithaca, NY, post office for what turned out to be a good while, and was eventually returned to Australia. But two months after writing it, on June 23, 1961, my father died. When my late mother, much younger than my father, came across the letter again in my father’s archives, it was too late for me to do anything about it. Nabokov had died.

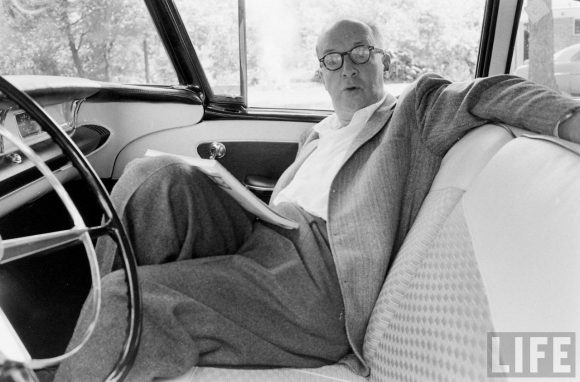

Nabokov, 1958.

At the end of the letter, my father refers to the elder Nabokov on a particular day just having been released from prison. It was not the first time that he had been imprisoned for his liberal views. In 1922, in Berlin where he edited the journal Rul’, attempting to thwart an assassination attempt on the politician Pavel Miliukov, Vladimir Dmitrievitch was shot twice and killed instantly.

23 Apr. 1961

Dear Mr. Nabokov/Vladimiir Vladimirovitch,

I read in Pnin, how you rode on a bicycle in the direction of the rose house on Morskoi, and I suddenly wanted to write you several words.

My acquaintance with you began with Lolita … I know the English language badly, but I was nevertheless unable not to admire your use of language, its variety, your freedom in using it/worth a dictionary all its own/the expressiveness, conviction. I unexpectedly felt in myself sympathy for the suffering of the hero. I suddenly registered that Lolita, in the end, is not morally disfigured. America is realized in such a way that, perhaps, the book could be banned there, but not at all for indecency.

Pnin has simply moved me and has forced me to remember the models of Russian classical literature. Now I am going to start reading your other books and anticipate much good from acquaintance with them.

These few words of greeting I write to you by right of my acquaintance with your father. For five years, I was the music critic for “Rech’,” where I would meet with Vladimir Dimitryevitch and would hear his speeches at the annual dinners of “Rech’.” Vl. Dim. was a Wagnerian. I remember him well at my orchestra rehearsal for “Das Rheingold” and a conversation about the horn in the first tableau. I met with him several times in Munich at the Wagner Festival, I was in your home, from the Nevsky on the right side, I believe No. 47, rose-colored. On that particular evening, Vl. Dim. was presenting the young violinist Miron Polyakin. Towards Vladimir Dimitryevitch my feelings always approached deep admiration. I liked everything about him, I considered him an aristocrat in the very best sense of that word. The last time that I saw Vladimir Dimitryevitch was November 27, 1917. I was conducting in the Maryinsky Theater the jubilee performance of “Russlan and Ludmila” (Chaliapin sang Farlaf). I come out to go to the podium—in the third row, to the right of the entryway, in one of the “official” places sits Vl. Dim. It was the day he was released from prison.* I pointedly stretched out my hand, Vl. Dim. came over to me, and I was able to welcome him.

With sincere greetings and my best wishes,

Nicolai Malko

* The elder Nabokov had already been imprisoned for his liberal views. In 1922, in Berlin where he edited the liberal journal Rul’, attempting to thwart an assassination attempt on the politician Pavel Miliukov, he was shot twice and killed instantly.

[Photo Credit: via George Malko; Carl Mydans, LIFE]