On May 16, 1955, James Agee, 45, died of a heart attack in a New York City taxicab while on the way to his doctor’s office. Elegized by the critic Dwight Macdonald as a literary James Dean, he left behind an idiosyncratic nonfiction classic called Let Us Now Praise Famous Menalong with one of those myths for hard-living and intemperate genius that are far more alluring to young writers than the idea that they are going to spend their working lives alone in a room, hoping that something interesting will happen on the blank screen in front of them. (There are days when more interesting things happen on a widget assembly line.)

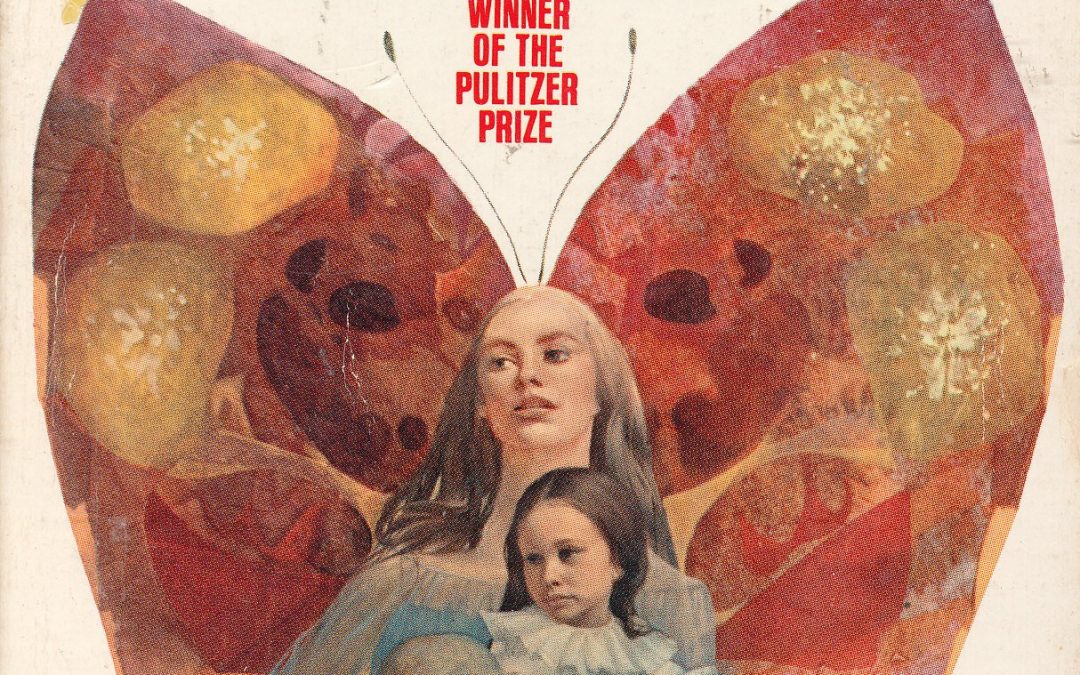

But Agee’s legacy also included a manuscript of an untitled and nearly finished novel in handwriting so crabbed that psychics should have been called in to decode it. David McDowell, Agee’s protégé and literary executor, jerry-built a version of that book, which is a lyrical autobiographical account of Agee’s first six and a half years, ending with the death of his beloved father in a car crash. A Death in the Family, as McDowell titled it, was published in 1957 to great acclaim and a Putlizer Prize —a happy ending for the novel, if not its creator.

Or so it has seemed for the last 50 years.

Enter the scholars, as they are wont to do, especially one Michael A. Lofaro. He appears to have spent years shuffling through the original manuscript to create A Death in the Family: A Restoration of the Author’s Text (University of Tennessee, $49.95), tracking down the variants, squinting at Agee’s gnarled handwriting, deciphering illegibilities, comparing drafts, speculating, emendating, annotating — and when it comes to his predecessor McDowell’s version, lacerating. The volume he’s restored with the care and caution of a divorce lawyer guarding his client’s assets is thick with such scholarly apparatus as fore-matter, after-matter, and probably a little antimatter, too.

The question naturally arises: What sort of novel have such ministrations produced? Has Lofaro rectified a grievous injustice done Agee’s masterpiece by his acolyte McDowell? But if it was already an acknowledged masterpiece, then how bad a job could McDowell have done? Have the new editor and like-minded revisionists merely been dancing on the nib of Agee’s pen, obsessive angels of the inconsequential?

Certainly, the two editions of the novel couldn’t start more differently. While the McDowell version opens with the famous prologue, “Knoxville: Summer of 1915,” a free-floating evocation of a summer dusk in that Southern city, so beguiling in its rhythms that Samuel Barber set it to music, A Death in the Family now begins with a nightmare in which the grown-up protagonist drags the decomposing corpse of John the Baptist through the streets of that same Knoxville. The rotting body is treated with the lyricism Agee normally lavishes on men watering their lawns in the twilight. When John’s head goes rolling down the street, the protagonist feels an agonizing tenderness. “He could not endure to chase and corner and trap it as if it were some frightened animal but gently shoring its escape with both hands, trying by the gentleness of his hands, without speaking, to assure it that it need not fear him, slid both hands beneath it and lifted its cold and gritty weight as if it were a Grail.”

That’s not your average interaction with a severed head, ladies and gentlemen, that’s a courtly romance.

Of course, one of Agee’s virtues as a writer is his willingness to heat up the rhetoric until it boils. At its best, his prose is incantatory, a Latin Mass for the Latinless, summoning up through sound alone a host of meanings. At its worst, the language can make readers feel as if they’re under assault by the wolf in The Three Little Pigs, huffing and puffing until he blows the novel down. Baby Rufus (Rufus was Agee’s childhood name), for instance, wakes in darkness and hears “in illegible antiphony the voices of the men and women he knew best.” Baby Rufus adores illegible antiphony.

In contrast to McDowell’s version, the Lofaro edition is organized chronologically, adding 10 new chapters, mostly elaborating on young Agee’s relationship with his father, Jay, and dispensing with the flashbacks that the former editor insinuated into the novel. McDowell’s first chapter becomes Lofaro’s 17th; rather than starting with Jay Agee’s fatal trip, the early chapters now embody the development of Rufus’s childhood consciousness, at times in painful imitation of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

In a scene present in both editions, the young Agee puzzles over the lyrics to “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” as his mother sings him back to sleep. “A cherryut was a sort of a beautiful wagon because home was too far to walk, a long long way, but of course it was like a cherry, too, only he could not understand how a beautiful wagon and a cherry could be like each other, but they were.” Even by Agee’s era, singsong prose as an embodiment of a child’s innocence must have been an exhausted trope. You can see the grown man’s 5 o’clock shadow darkening the smooth cheeks of such baby prose.

Until the wreck, which impacts Agee’s world like the asteroid responsible for killing the dinosaurs, the novel is a marvel of dailiness, a loving recreation of meals, bedtimes and conversations that knit together the family. Jay and his wife, Laura, bicker about her serving Postum rather than coffee. Father and son go to the movies to watch Charlie Chaplin (“that horrid little man,” Laura says). And in one of the new chapters, the extended Agee clan goes for a drive in Jay’s recently purchased and doomed Model T.

So which version is better? I’d say the new edition, though the nightmare-prologue could have been recited in a therapist’s office to greater effect. The novel improves without McDowell’s flashbacks, which block the narrative’s quietly tragic flow. The wreck is more devastating now. With the mountain-bred Jay’s enlarged role, the story is also more rooted in a specific place, more Appalachian. This further heightens the contrast between husband and wife, who are already engaged in a subterranean war over Jay’s drinking and lack of religion.

At last we have A Death in the Family that appears closer to the author’s original intention. This tidying is good in its own right, but the main reason to celebrate the publication of this version is that it serves as a fresh reminder of the wondrous nature of Agee’s prose—unabashedly poetic, sacramental in its embrace of reality, and rhythmical as rain on a Tennessee tin roof.

“One by one, million by million, in the prescience of dawn, every leaf in that part of the world was moved.” Why don’t our novelists write in Agee’s tender high style these days? Either something has gone out of the world, or something has gone out of them. His book reads like a prayer, an attempt to breathe life into the dead through mighty exertions of language. Everything is consecrated. Trees move in their sleep, stars tremble like lanterns, and a butterfly—yes, a butterfly—alights on a coffin.

In the end, all that a writer has to pass on is not myth and anecdote, but scene and character, evoked in memorable prose. The beauty of A Death in the Family is that the child’s point of view that begins the book eventually widens until readers may feel they are seeing into the very heart of existence — the utter strangeness of being alive in a particular family at a particular time and place. What more could James Agee leave behind?