“That’s Barbara Walters over there,” Roy Cohn tells me, pointing helpfully to the other corner table along the front wall of Le Cirque. The second-best corner table. Roy’s got the best, the one with the wide-angle view of the mirrored, flowered, high-powered array of Le Cirque at lunch.

I’ve just arrived—a little late—and as I settle into the turquoise banquette to the left of Roy, he fills me in on what’s been going on at this lunchtime playhouse for all of those people you read about in “Suzy Says.”

It seems, Roy tells me, that Barbara Walters is interested in seeing if her old friend Roy can can help persuade Archbishop O’Connor to sit down with her. Alice Mason, who’s at the banquette on the left, has leaned over to ask Roy’s help in getting Claus von Bülow to come to one of her parties this fall. Archbishop O’Connor, Claus von Bülow. An odd pairing to be sure, but just two more of that many and varied tribe who constitute the Friends of Roy Cohn.

Could there be a bit of poetic justice, well, poetic resonance here in Roy Cohn’s helping the newly presumed-innocent Claus to get back into the social swing of things with the Le Cirque crowd? After all, there was a time when Roy himself was about as unwelcome as Claus in certain circles of what he likes to call “the stuffed shirt establishment.”

That was back in the sixties, when Roy himself faced three separate federal indictments for conspiracy, bribery, and fraud, and it looked like the brash Bad Boy of the McCarthy era was about to get taken to the federal woodshed for a while.

But it didn’t happen that way. Roy won three acquittals, and in the years that followed, the onetime Bad Boy has risen to almost elder-statesman status in the Reagan conservative establishment. He’s a regular figure at the best tables at “21” and Le Cirque, a power broker among Permanent Government types in both political parties. His widely publicized birthday bashes draw a fusion of the powerful, rich, and famous. So many local judges attended a party for him on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his admission to the New York bar that the New York Times editorial page questioned the propriety of all those judicial figures nibbling on Roy Cohn’s anniversary cake. (Roy tells me that he thinks Times editorial-page editor Max Frankel, the official voice of the “stuffed shirt establishment,” has it in for him.)

Of course it wasn’t easy: It took Roy about ten years after his last acquittal to go from Mr. Outside to Mr. Inside. It seems to have taken Claus less then ten weeks. Perhaps this difference can be attributed to Claus’s blue-blood demeanor. Complete respectability—which for Roy seems to mean the approval of the Times editorial page—still eludes Roy. Perhaps because he continues to delight in being, in one way or another, outrageous. This is the man, after all, who just recently called Mr. Justice Respectability, Felix Frankfurter, “a $50,000 political pimp.” This is the man who speaks with relish of the scorched-earth policy he pursued in concluding one bitter divorce case in which he represented the husband:

“We got an order evicting her from the apartment but she wouldn’t go,” Roy tells me, “so we just pulled up moving trucks, broke down the door, moved everything out of the apartment. But she wouldn’t go. She got into the bathroom and locked herself in. [Her lawyer] called me and said, ‘What are you gonna do about her?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know, in a couple of weeks we’ll send somebody around to pick up the bones.’ ”

Roy waves to Barbara Walters in her corner. Barbara waves back.

“When I used to go out with Barbara,” Roy tells me a bit later, “we used to argue extensively about one thing.”

What thing?

“Jewish dinner parties,” Roy says. “The kind where I’d be seated between two women and all they wanted to talk about was what Joe McCarthy was really like and were the Rosenbergs guilty.

“It took Barbara a long time to realize how important she was,” says Roy, a man who has never suffered from this disability. “When she finally did realize it, she realized she didn’t have to go to them anymore.”

At lunch today Roy has more congenial company. Sitting across the corner from us is old friend and sometimes client Paul Hughes, chairman of one of Revlon’s international divisions.

“Paul and I go back a long time,” Roy says. “To when we owned the heavyweight championship together.”

The heavyweight championship. This is an aspect of Roy’s varied career I hadn’t been aware of. But before he gets to explain, it’s time to order.

Paul orders the salmon. I choose the rabbit stew. Roy orders tuna fish salad “my way.”

Tuna fish salad at Le Cirque?

Roy has refined the notion of the power lunch to a new level of purity at Le Cirque: all power, no lunch.

“I only have tuna fish salad wherever I go,” he explains. “And I only like Hellmann’s mayonnaise, so I make sure to keep a jar of Hellmann’s in the kitchen back there. Remember when we were in Majorca,” he reminisces with Paul, “and we had everybody flying the tuna fish in for me?”

“When did you start this tuna fish thing?” I ask Roy.

“I’ve been doing it for about twenty-five years.”

“Is it some kind of health thing?”

“No, I just like it. I like American lunches,” he says.

Not all restaurants cater as assiduously to Roy’s tuna fish thing as Le Cirque; “21” does. They keep a jar of Hellmann’s for him there. “But there’s another restaurant that I like, Paone, which is patronized by William. F. Buckley and Meade Esposito—at Paone’s they won’t make tuna fish specially for me,” Roy complains. “There I have to bring it in.”

“So do you just sit down and unwrap your takeout tuna?”

“At first, yes,” he says. “But now they unwrap it for me.”

Roy’s other food obsession, he says, is iced tea. “At some point I got the compulsion to carry a glass of iced tea around everywhere. I leave the house in the morning at eight o’clock; people think it’s Scotch.”

So he arrives at Le Cirque with his own iced tea, and he eats the Bumble Bee brand tuna they bring in for him with the Hellmann’s he supplies. It occurs to me that Roy has refined the notion of the power lunch to a new level of purity at Le Cirque: all power, no lunch.

Now about that heavyweight championship business. It is a part of Roy’s fascinating post-McCarthy odyssey I’d never heard of. I know that after the senator’s decline in the mid-fifties, Roy had been taken up as adviser and confidant by various flamboyant tycoons such as Lewis Rosenstiel of Schenley, and Charles Revson—fearsome self-made tyrants with McCarthy-like temperaments, known for bullying subordinates. I know that in the early sixties he had gotten involved with some high-flying financial speculators who were in on the first flush of takeover fever during the go-go years. There was a short-lived attempt to take over Lionel Corporation (the toy train company) and turn it into a defense-contracting electronics conglomerate.

Then in the mid-sixties the indictments came down. The result, Roy has always claimed, of a “get Roy Cohn vendetta” ordered by then attorney general Robert Kennedy. A claim that seemed to be substantiated several years ago when former assistant U. S. attorney Irving Younger confessed in Commentary that he had been ordered to “get” Roy Cohn and that he’d used questionable methods to do it.

I knew that throughout this turmoil Cohn had continued to build on his reputation as a high-priced, highly effective hired gun for big-stakes legal shootouts. That he’d won acquittals for various alleged underworld figures like Tony Salerno. That he was, as Bill Murray might say, “a real party animal,” a constant fixture of the high life and the night life of the city: afternoon lawn parties with Buckley conservatives on their Connecticut estates and late-night parties with the Studio 54 demimonde.

I remember coming upon Roy Cohn while I was covering the 1980 Reagan inaugural ball. There he was in black tie, seated in a Washington hotel ballroom with his law partner, Tom Bolan, and Senator-to-be D’Amato (who named Bolan to his screening panel for federal judgeships). Donny Osmond or somebody squeaky clean was bubbling away at the mike. That first week in the White House, Reagan’s inner circle of aides would give a private dinner party for Roy in appreciation of his advice and counsel during the campaign. Mr. Outsider had become Mr. Insider. And yet he look bored. He looked like he missed the days when he would stroll into the Stork Club and pick up the heavyweight championship of the world for a song. For a lark. For the hell of it.

Roy and Paul speak fondly of that heavyweight champion escapade. It’s a long tale involving a Runyonesque character by the name of Humbert (Hard Luck) Fugazy.

“So we go to Hard Luck Fugazy,” Paul recalls, “and I say to Hard Luck, ‘Roy and I have got a chance to buy [Floyd] Patterson’s contract for five thousand dollars,’ and Hard Luck says, ‘Do it,’ so … ”

“The parties for these fights were great,” Roy says. “All black tie. We had Gary Cooper, Liz Taylor. Used to be a big social event,” he recalls wistfully. “What a great time we had with it.”

The conversation shifts from the heavyweight bout to a little legal sparring match Roy has been engaged in on behalf of Donald Trump.

“There’s this guy … a businessman named Julius Trump,” says Roy. “No relation. Now as long as he stays Julius Trump … fine. But he’s got this thing he calls the Trump Group and he’s making a buyout offer on some discount chain, Pay ’n Save, something like that. So Donald Trump sees the ads Julius is taking out for this Trump Group and he hits the ceiling. ‘He’s trying to pretend he’s me,’ he says, and he tells me to get an injunction. I go to court tomorrow.”

Roy’s also going to bat for George Steinbrenner in his embittered litigation with his outfielder over Steinbrenner’s financial pledges to the David M. Winfield Foundation.

“I want to see the books,” says Roy. “I’m concerned about how much of it is actually going to charity,” he says, with the air of an injured altruist.

Roy seems to enjoy playing the hired gun called in to tackle the tough ones for lone-wolf tycoons tired of timid establishment law firms.

Onassis, for instance. Roy tells me the story of the time Ari called him to consult about instituting divorce proceedings against Jackie.

“It started over this totally different thing,” says Roy of his involvement in the putative divorce action. “It started over this popparuzzi [sic] business.”

The “popparuzzi” business was Mrs. Onassis’ invasion-of-privacy suit against photographer Ron Galella. According to Roy, “Ari didn’t want her to bring the case, right as she might have been—all she was doing was giving this guy millions of dollars of free publicity. Now Onassis was a pretty shrewd guy, so he said to her, ‘You want to do it, I can’t tell you not to do it, but I’m out of it.’ Till the lawyer’s bill came. A big fat bill came. And he went berserk. At that point, Johnny Meyer, a good mutual friend of all of us who used to work for Howard Hughes, called me and said … ”

The noise level in Le Cirque drowns out Roy’s voice on my tape at this point. He’s saying something about his advice to Onassis. “ ‘…Use my name, then go back to them and say you’ll have to go to court to collect. I’m sure you’ll get a good price that way.’ It was the next time I spoke to him that it came up,” Roy says, referring to Ari’s divorce intentions. “There would have been a New York aspect to it because of all his properties here, and he wanted to know if I would be available. The New York Times found some memo from one of his people to him about it. And the basis was two things. The money, her spending. And also she seemed never to be where he was all the time. Of course he died before he took any action …. ”

Roy’s karma with the Kennedy family certainly has been turbulent over the years, hasn’t it? I ask him if it is rue that it could all be traced back to a fistfight he and Bobby Kennedy got into when the two of them were counsels for the McCarthy committee.

Roy says it goes back to before the fistfight, to the very first moment they met in the committee’s Senate office. Bobby had wanted the chief counsel post that Roy got, even though, says Roy, “Bobby didn’t have any experience. I did. I had prosecuted the Rosenbergs. So when I got to the office I’d never met Bobby, but he started looking me over, sizing me up and—”

At this point there’s a curious interruption. A very well dressed, stately woman glides over to Roy’s table. She smiles and waves at Roy with standard Le Cirque effusiveness but seems to have something on her mind.

“When will you release my one hundred fifty?” she asks Roy.

“That is not up to me,” Roy says in a tone that suggests he’s made this point at least once before. “That’s up to [a law firm] and my co-executor.”

“But with your power,” she says sweetly, with a hint of iron beneath the honey.

“But I have to find a sound basis for exercising my power,” Roy says. “Have your lawyer file a claim,” he says with finality.

“Couldn’t you come over for cocktails and explain all this to me?” she persists with that surface sweetness.

“Just call me,” says Roy.

“I can call you?” she asks.

“Call me,” Roy repeats.

At this point Roy and Paul get sidetracked into an anecdote about Henry Kissinger being photographed next to “a couple of very well-endowed women at an international conference.” There is considerable chuckling before Roy returns to the year 1953 and Bobby Kennedy “sizing him up.”

Yeah, so he’s sizing me up and he says, ‘Morton Downey thinks you’re the greatest guy in the world. Other friends of ours don’t trust you.’ And I say, ‘So what am I supposed to do—am I being graded on trust or something? Am I supposed to make a defense? I’m prepared to state Morton Downey’s right.’ ”

Not long afterward, Roy says, a woman told him that she received a message for Joe McCarthy from “someone in the Kennedy family” while she was in the Senate beauty parlor. The message was “He’ll never do anything to hurt Joe McCarthy, but he’s gonna get Roy Cohn.”

“I never knew why,” Roy says, all injured innocence. “I don’t know if it was our different backgrounds, milieus, religions. I don’t know,” he says.

Well, what about the fistfight?

It began, Roy says, over Bobby’s behavior while Roy was giving testimony during the Army-McCarthy hearings.

“Bobby is sitting directly behind the three Democratic senators, staring at me. He has this real evil grin, and every time his eyes meet mine he breaks into this grin, and it really started getting to me. He was feeding them questions for me, asking questions like crazy—and that was the immediate thing. We ran into each other afterward. I said something to him. He said something to me and he started screaming at me, and I started screaming at him, the bastard. Then I said, ‘Come on, let’s step outside,’ and Senator Mundt, who was horrified, followed us out.”

Who won?

“Well, Mundt stopped it before it really started. For which I’m glad, because although I’m not lacking in self-confidence, I don’t go climbing mountains or go rafting on rivers,” he says, mentioning Kennedy family pursuits. “Bobby got terrible mail on the fight,” Roy says. “Mothers all felt sorry for me.”

There’s a fascinating postscript to this inspiring tale of dedicated public servants: Roy’s story of the final face-off between himself and Bobby, almost fifteen years later.

But before we get to that, I’d like to describe Roy’s tuna salad which arrives about now along with Paul’s salmon and my rabbit stew. Do you know those women’s magazines by supermarket checkout counters that are always featuring cover stories on “How to Turn Plain Old Tuna Salad into a Fantastic Tuna Fiesta”? Well, some dutiful soul back there in the kitchen of Le Cirque has opened a can of Bumble Bee, gotten Roy’s jar of Hellmann’s down off the shelf, gone to work with some bits of exotic greens here, a few shallots there, and turned plain old tuna salad into a Fantastic Tuna Fiesta! I couldn’t help wondering: When Richard Nixon comes here, as he does more than occasionally, do they do some fabulous thing with cottage cheese and catsup for him?

But to return to the Final Showdown between Cohn and Kennedy. The place was Orsini’s restaurant. The Le Cirque of its era.

“I went there with ———— and a couple of girls,” Roy reports. “We’re sitting at a table and Bobby Kennedy comes in with Margot Fonteyn. They put him at the next table. Well, we stop talking. They never started talking.”

The Kennedy and Cohn tables sat there in silence until, Roy says, “I get up and go over and say, ‘Look, this is ridiculous. We’re gonna ruin your evening and you’re gonna ruin our evening. Why doesn’t one of us move?”

What a great New York moment. Roy Cohn and Bobby Kennedy facing each other down with dire threats of ruined dinners hanging in the air.

But then, according to Roy, “Bobby said, ‘You’re absolutely right. Since you were here first, we’ll move.’ So he moved, and that was the very last time I saw him.”

“When was that?” I ask Roy.

“Shortly before his death.”

He sounds regretful, a fighter mourning the loss of a particularly hard-punching sparring partner. Still, is it my imagination, or could the inclusion of Margot Fonteyn in the anecdote be construed as what they used to call, in the McCarthy era, an innuendo? One final jab at Bobby?

So here’s Roy Cohn sitting in splendor at Le Cirque. He’s gotten what he wants out of life; there’s no one out to get him anymore. He’s got a Connecticut estate, a Manhattan town house, a lavish lifestyle; he’s a power broker respected and feared by the Big Boys. I remind Roy of a quote in a story about his re-ascendance that ran in the Times several years ago, in which he said he’s still fighting “the stuffed shirt establishment.” Doesn’t he feel like he’s part of the establishment now?

“Oh no,” he says quickly. “I’m not part of the establishment. God forbid. I can’t stand those people. I dislike them as much as they dislike me. See, I don’t like to be the only Jew. I’m not impressed by the fact I could get into X Club; I don’t want to get into X Club if they don’t approve of Jews and so forth.

“There’s nothing abut the establishment I like,” Roy continues. “I don’t like golf; I don’t like Saturday afternoon cocktail parties with the three martinis at the club; there’s nothing in my profession the establishment has to offer. The establishment law firms look down on matrimonial cases, they look down on criminal cases—everything I find exciting and challenging. It comes up a lot over my representation of so-called underworld figures,” Roy says.

He assures me, “They never tell me anything about the underworld, so I don’t know if that’s what they are, although some I might deduce. But I’ve met a couple of them I respect, that I just like. One of them’s Tony Salerno, who’s supposed to be the big sports gambler.”

Roy got Tony Salerno off on income tax charges. He says he likes Salerno “as much as any person in the world. He’s refined. A quiet, peaceful person. He’s a sports gambler.”

Roy has a lot to say oft the subject. It seems to be a sore point.

“People say to me, ‘Why do you choose to represent them?’ And I say, ‘I’m not their consigliere or whatever you call it.’ ” Roy makes a big distinction between what he does and what is done by “real mob lawyers,” a class of attorneys he has no great respect for.

“I have enough of a varied practice that I can’t get tagged as a mob lawyer. I don’t like mob lawyers. I can’t stand them. Know why? They have only one thing to sell. Loyalty. They’re very loyal. There’s only one problem. They lose practically every case.”

Roy says that certain people occasionally ask his opinion of this mob lawyer or that, often describing the mouthpiece in question as “a stand-up guy.”

“I say, ‘You’re damn right, he’s a stand-up guy. Do you plan to use him as a witness? Oh. You plan to use him as a lawyer. Well, when you find out when he last won a case, tell me about it.’ ”

Mob lawyers are that incompetent? I ask Roy.

“Yeah,” he says. “Now Carmine Galante, Nicholas Rattenni—they had the sense to go to a nonmob lawyer. Namely myself.”

I think it’s about this time I first take notice of the wallpaper at Le Cirque. It’s kind of peculiar: Our corner, anyway, is dominated by a fanciful scene of chimps—or are they orangutans?—dressed up in the beribboned and ruffled costumes of milkmaids. Specifically, the sort of elaborate, expensive mock-milkmaid garb adopted by Marie Antoinette and her ladies-in-waiting when they played at being peasants in the gardens of the Petit Trianon.

Somehow this image of expensively attired primates seems a particularly apposite one when Roy begins to launch into his epic tales of divorce wars among the filthy rich.

I wish I had the space to record here all his tales of unholy matrimony, tycoons and fortune hunters, some of them rivaling in their lurid appeal the ones Truman Capote retold in his notorious “La Côte Basque, 1965.” And like those stories—in their own Way—these are morality tales. Le Cirque 1984 is a spiritual descendant of Côte Basque 1965, or if you prefer, Petit Trianon 1789.

In fact, if Capote was the Proust of Côte Basque, you could call Roy Cohn the Homer of Le Cirque. The man is an inexhaustible storyteller. And if he is the Homer of Le Cirque (okay, I said if), the story of his most bitter divorce case—the epic battle over the Rosenstiel divorce—is Roy Cohn’s Iliad.

Roy Cohn seems to me someone who early in life was initiated into the intimate rituals of unspoken power enacted behind closed doors.

By the time Roy really gets into the Rosenstiel story, we’ve been at Le Cirque almost three hours. The place is entirely empty except for the three of us at Roy’s corner table. Roy has spent the last hour rhapsodizing over the virtues of Ronald Reagan and gossiping about White House intrigues. How so-and-so screwed himself out of the Treasury post. How, as Roy put it, David Rockefeller sent Henry Kissinger to Gerald Ford to convince him to make a last-minute run for the presidency in 1980. How Kissinger and Alan Greenspan went to the convention in Detroit and tried to persuade Reagan to adopt the bizarre plan whereby Ford would accept the vice-presidential nomination with assurances he would be some sort of “co-president.” (These Kissinger stories sound like a Trilateral Commission conspiracy theorist’s fantasy, but Roy says he knows they’re true.) How Reagan campaign aides discovered Roy’s name on Geraldine Ferraro’s congressional campaign contribution list and revoked his credentials at the Dallas convention this August—as a joke. (Ferraro “comes to my birthday parties,” Roy says.) How there’s only one Democrat who frightens him: Mario Cuomo. (“He’s tough,” Roy says, respectfully. “I saw one thing he did that scared me. When he was debating Lew Lehrman, Cuomo gets up, goes over to Lehman, grabs him by the wrist, and holds it up people can see this expensive watch Lehrman’s wearing. Then he asks the audience, ‘Now, how many of you can afford a watch this expensive?’ Wow,” Roy concludes “if I were Reagan, I’d stay a million miles away from anywhere Cuomo is.”)

Great stories, but nothing compared with the Rosenstiel divorce wars, in which Roy went head to head with Louis Nizer, who was representing Susie Rosenstiel, the fourth wife of Roy’s client, liquor tycoon Lew Rosenstiel.

Just the mention of Susie Rosenstiel reanimates Roy. His eyes light up as he describes the way he and Nizer went at it, springing secret injunctions here, pulling surprise judgments in obscure jurisdictions there.

“Susie,” Roy says, “My God: We were in Connecticut, Florida, New York, Mexico on that one.”

“Susie,” says Paul, “I see her sometimes …. ”

“She’s in Paris,” Roy says in an almost awestruck whisper. “You know who ran into her? You know, the guy who sits at that table over there. I ran into him in Monte Carlo a few weeks ago, and he was telling me he ran into her in Paris,” he recalls. “Look at the repercussions of that case—Senator Javits’s brother was suspended from the bar.”

The problem, Roy says, was some tricky abrogation of an annulment decree of a previous marriage.

“That’s where I came in,” Roy says.

“Well what was it about this legendary woman?” I ask Roy. “Was she incredibly beautiful?”

“No, it wasn’t that,” he says. “Lew Rosenstiel was a very susceptible guy when he met her. His crushing marriage was to the present Mrs. Walter Annenberg, Lee Annenberg. She [divorced] Lew [and married] Walter Annenberg and he never really got over that.”

He proceeds to tell the fascinating tale of how the future Mrs. Rosenstiel wooed the susceptible tycoon.

“The story’s told, and I can’t prove this,” Roy says, “that Susie found out when—you see, Lew would go to Europe once a year and meet the liquor trust, the DCL heads. And they never signed a written contract like on his franchise deal with Dewar’s; there would always be a raising of a finger, that would be the deal.” Roy raises his index finger to illustrate. “He’d get off the boat, and they’d have lunch in some hotel, they’d shut the doors, they’d make the deal, they’d all raise their fingers, and then he’d go home.”

Well, according to Roy, Susie just happened to book passage on the Queen Elizabeth when the lovelorn liquor tycoon was on board for one of those finger-raising trips. “And then, you know, she’s walking around the deck and then she sits down next to him. He loved cards. So she played cards with him and the one who lost would take the other for dinner in the Verandah Grill. So she lost, she took him to dinner in the Verandah Grill, and they came back and she moved in, and that was that.”

There’s something about this tale that fascinates me. It’s not the evocatively Art Deco courtship story. No, it’s the part about the liquor trust and the raising of the fingers behind closed doors.

Roy Cohn seems to me someone who early in life was initiated into the intimate rituals of unspoken power enacted behind closed doors. The vision of life that he has developed from knowing too well the way the world works—you could call it cynical. You could call it realistic. You would probably not call it idealistic. In its awareness of the corruption of human nature, of the dark springs of human motives, you might best call it conservative.

These tales of Rosenstiel prompt Roy and Paul to lament the passing of the Revson and Rosenstiel breed of self-made tycoons.

“That was an age of giants,” Roy says.

Paul agrees. It sounds as if they miss the high-powered, heady excitement of those days, when they were on the outside nipping at the heels of respectability with the lone-wolf tycoons. One gets the feeling that Roy Cohn is finding his renaissance of respectability a bit boring. Yes, his life is a Fantastic Tuna Fiesta, but part of him—the part that’s attracted to the raffish and the Runyonesque, the “sports gamblers” and the demimonde—misses the old days, misses the thrill of combat.

Probably even misses Bobby Kennedy.

As I leave the four o’clock dimness of Le Cirque and all these tales of the way the world really works, it suddenly occurs to me: I miss Bobby, too.

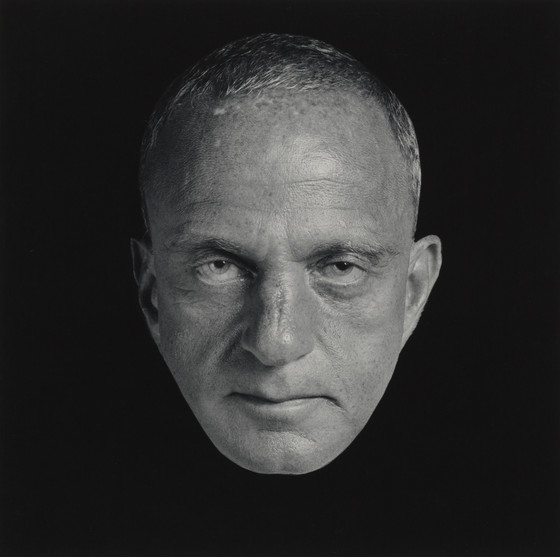

[Photo Credit: Robert Mapplethorpe c/o LACMA]