Barney Rosset is being kissed. He leans forward toward her lips, which are delicately painted. His old hands clasp her young hands—right in left, left in right. She is small and slender. So is he. Later, after she smiles winsomely and leaves him, he will remark matter-of-factly that her breasts are very small for the line of work she has chosen. It is nearly 2 a.m. and Rosset is leaning back on the bar in one of his nocturnal haunts, a seedy Chelsea club called Billy’s Topless. Despite pounding rock music and three young women gyrating in G-strings on a small stage backed with mirrors not 10 feet from him, Rosset pays little attention to the show.

Their lips do not linger. It is a warm kiss, but only friendly. She asks how he has been. He asks after another dancer he knows better, with whom he has recently traveled to Thailand. Not back yet, the young woman tells him. Then she smiles and says it is good to see him and turns to the tough labor of exhibition, titillation, and seduction, sucking roughly on a beer bottle just before she launches herself onto the carpeted stage and begins removing what little clothing she has on.

“She’s a Bennington girl,” Barney Rosset reports as the young woman walks off. “There are a lot of them that work here. I’ve hired a few to work for me.” He takes a sip of his drink—rum and Coke in a small glass—and surveys the three dancers onstage. Rosset is 67 and his hair is white now. He laughs quickly, particularly after a few glasses of rum and Coke, the mixture he uses to chase the jug of martinis he mixed for himself earlier in the evening. An impish quality saves him from seeming merely what the more judgmental might call a dirty old man. There is no desperation in his being here among the desperate. He comes to Billy’s because he likes to watch young women dance, and it’s in the neighborhood. He often brings friends.

Besides being one of the few men in Billy’s Topless without a visible tattoo, Rosset is probably the only one in attendance this evening who is a close friend of Samuel Beckett. He is certainly the only man among the leering crowd who has spent thousands of dollars on legal fees defending the rights of his strip-joint compatriots to read about or watch the depiction of sex.

Last fall, PEN, the writers’ organization, gave Barney Rosset its Publisher Citation “for continuous service to international letters and to the freedom and dignity of writers.” Alfred A. Knopf was a recipient. Roger Straus and Robert Giroux have been cited. The awards committee wrote that Rosset had, during his 35 years at Grove Press, “exploded a few conventional ideas about what literature is; where it comes from; how it’s put together; what it looks like on the page.

“Barney’s genius was to be in tune with the tenor of the times in a totally unself-conscious way.”

“He had an uncanny ear for the sound of contemporary writing,” the committee noted, “its immediacy, its irreverence, its pugnacity, its lyricism.”

These days Rosset hires people to work for Blue Moon Books, a small press he runs from a lofty apartment on Park Avenue South that also serves as his New York digs. The most recent catalog for Blue Moon is a document that might interest the guys at Billy’s tonight, some of whom are now virtually jostling one another for the chance to slip dollar bills to the Bennington girl Rosset has just kissed, showing their approval of her rather glandular dance technique.

Among the 50 books on Blue Moon’s spring list is a series of four erotic novels by one Ahahige Namban, set in 17th-century Japan and involving “sensual and bloody adventure” with a cast of shoguns, samurai, sumo wrestlers, and, in three of the books, the “beautiful blonde prisoner Rosamund.” Another group of graphic novels, by Daniel Vian (pen name of a disaffected college professor, Rosset reveals), takes place in Europe in the years between the wars, winding up in occupied Paris in 1941, where the lovely Simone “begins a series of erotic entanglements with German officers” and, in one memorable scene, indulges her obsession with the Nazis by masturbating while gazing at a photo of Adolph Hitler. A recent release, Gabriela and the General, chronicles the erotic adventures of a young woman in a politically tumultuous Latin American country. It’s what he’s always done, Rosset says. Sex and politics.

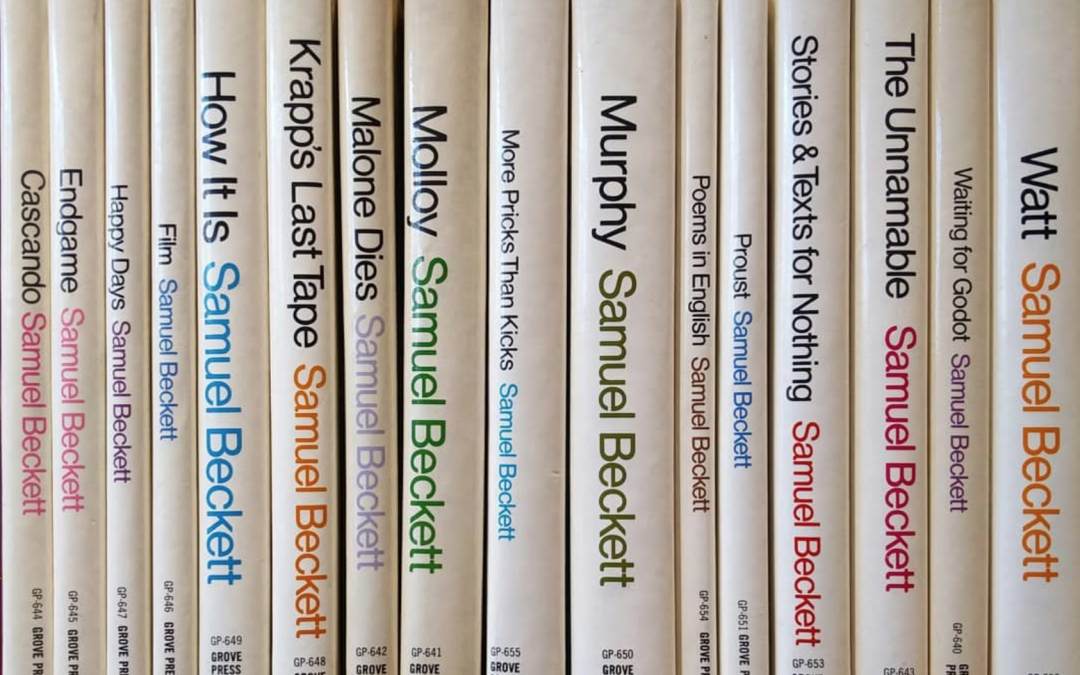

There was a time when Rosset bridled at being described in America’s great middle-of-the-road magazine Life as “the old smut peddler.” But that was 20 years ago, when he and his publishing company, Grove Press, were riding a wave in the Zeitgeist, publishing the unexpurgated novels of Henry Miller, the Autobiography of Malcolm X, the anti-novel novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet, William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, John Rechy’s then-shocking story of homosexual hustling, City of Night, and even, in another vein, the pop-psych best-seller Games People Play. Almost single-handed Barney Rosset brought the European avant-garde to America—all of Beckett, much of Bertolt Brecht and Ionesco—and later their American brethren David Mamet and David Rabe.

It all began in the late ’50s when Rosset mounted an assault on repressed America, bankrolling the legal fight to distribute D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Rosset won, and the book became Grove’s first best-seller. The next year an emboldened Rosset released Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, which for years had been banned in this country. Taking the case all the way to the Supreme Court, Rosset and Grove won again. All along Barney Rosset published smut, particularly a soft-core genre known as Victoriana. “Barney was always interested in that stuff,” says a former Grove executive. “And it helped pay the bills for years.”

Barney Rosset does not believe in watering things down.

In 1970 Rosset added a film distribution company to his publishing business to bring the so-called “pornographic” Swedish import I Am Curious (Yellow) to American viewers, and reportedly made millions doing it. He certainly garnered publicity. By the early ’70s Rosset had been profiled not only by Life and The New York Times Magazine but by that bastion of the American heartland the Saturday Evening Post, whose cover featured a caricature of a ferretlike Rosset clambering out of a manhole. Tonight, getting ready to leave his apartment-office for the evening, Rosset brags that one of his Blue Moon books has gotten a terrific review in Screw.

Three years ago Rosset was forced out of Grove Press, which he had bought for $3,000 in 1951 when he was just out of the Army, a Chicago rich boy drawn to Greenwich Village. After 35 years of making literary history, Rosset is in the unenviable position of starting over at the point when most people retire.

In 1985, in dire need of money (not for the first time in his publishing career), Rosset sold Grove to Ann Getty, the super-rich, super-glamorous wife of Gordon Getty, and her partner, the British publisher Lord Weidenfeld, who was looking for an American base. Getty paid Rosset about $2 million for Grove (although he says his actual take was substantially less) and, according to Rosset, promised to keep him on as CEO with full autonomy. Little more than a year later Rosset sat down at a board of directors’ meeting of the Wheatland Corporation, Grove’s new parent company. As the meeting progressed, Rosset found the talk taking an ominous turn. “Just who is running Grove?” he asked George Weidenfeld icily. Dan Green, he was told smoothly, a former Simon & Schuster executive who had published Jane Fonda’s Workout Book, was the new CEO. Rosset sputtered out a wild offer to buy Grove back for $4.5 million—$4.5 million he didn’t have.

He could stay on as senior editor, he was informed and, in the words of Weidenfeld, “acquire new authors and do what he has always done best.” Rosset quit and sued Weidenfeld and Getty for more than $6 million. They settled out of court, and Rosset promised that until 1990 he would stay away from Grove authors—unless he got Grove’s permission to do otherwise. Now he is a smut peddler by default, although in April Grove allowed him to bring out a limited edition of Samuel Beckett’s latest work, with a $1,700 price tag and a dedication to Barney Rosset.

At dinner one night at the Chelsea Hotel, crash pad to generations of bohemians, he talks about a book he wants to publish: the autobiography of a woman he once lived with whose story encapsulates the black experience in the 20th century.

In 1964 Rosset and Grove snapped up the Autobiography of Malcolm X after Malcolm was assassinated and the original publisher, Nelson Doubleday, decided the book was too incendiary to release. Rosset got to know Alex Haley, who had ghostwritten Malcolm’s story. Haley had another book in mind, an examination of his roots. Though Roots became a giant best-seller and hit television miniseries, Rosset says, “Haley really watered it down. It wasn’t the book he had talked to me about.” Barney Rosset does not believe in watering things down.

So now he wants to hire a ghostwriter to help his old friend tell her story. (It would be nothing new for Rosset to mix his business and personal lives. Twice he married women who started out in low-level jobs at Grove. Another time he married his baby sitter. “Barney,” says a Grove employee fondly, “goes through women like some people go through underwear.” Former employees tell tales of Rosset and one of his wives having screaming fights over the intercom at the Grove offices.) Rosset sips on a rum and Coke and picks at a small lobster. He remembers one night when he hosted a dinner party with Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, and Ginsberg’s boyfriend at the time. They ate and drank and took LSD. Rosset and his woman friend went into a bedroom, where an Abstract Expressionist painting attacked them. “The shapes were coming out from the wall at us,” Rosset says, taking his hands from the lobster and pushing at the air. “I had to get up and go and push them back onto the canvas.” Meanwhile, Leary and Ginsberg and the other man danced together on the roof. His woman friend ended up leaving Rosset and running off with Leary. Rosset thinks she could talk a terrific book.

He stops eating and looks across the table. With the right expression, he’s a dead ringer for Jason Robards. “I can’t afford to publish it,” he says. “I guess I could act as an agent and put the people together. I’ve never had to do that before.”

After dinner Rosset says, “May I suggest we stop in two places. Pat’s and then another place.”

Pat’s is a neighborhood bar in Chelsea. As Rosset pushes through the doors into the dark barroom he is greeted by Ralph, the night manager, a big black man in a spiffy suit who brightens when he sees Rosset. He wraps his arms around the gaunt Rosset in a bear hug. He solicitously finds a barstool. Last fall, to celebrate his award, PEN threw a nice, staid publishing-world reception for Rosset at the Yale Club. After that Barney Rosset invited all his friends back to Pat’s.

“He’s altered the climate of publishing to everybody’s advantage.”

Tonight, Rosset orders another rum and Coke and launches into the tale of his failed attempt in the mid-’60s to find Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara before he was killed in Bolivia. It is a classic Barney Rosset story, in which he combines his role as activist publisher (he wanted to print Guevara’s diaries in Grove’s periodical of the time, Evergreen Review—where Ginsberg’s “Howl” first appeared) with his role as political leftist (he was under FBI surveillance for decades, he says, and has boxes of files he obtained under the Freedom of Information Act to prove it) and his role as boulevardier (he mentions the peculiar drunkenness achieved in Bolivia’s high altitude and the South American brothels). When the issue of Evergreen with Guevara on the cover came out, someone threw a grenade into Grove’s offices. Rosset retaliated by commissioning a massive building on West Houston Street—“the fortress”—that served as Grove’s headquarters and Rosset’s Manhattan home until he sold it in 1986, vowing he would use the money to wage his lawsuit against Getty and Weidenfeld.

Even now, of the handful of nonerotic books Rosset has published since leaving Grove, one was Two Dogs and Freedom, a book of essays by South African children that was banned in South Africa. In talking about a former Grove editor who runs his own publishing house, Rosset praises his editorial judgment but chides him for having no strong political convictions. “To me, it’s like being crippled,” he says.

After he finishes his second drink at Pat’s, Rosset says good night. “Done early tonight, Barney,” the bartender says, as Rosset heads out the door toward the evening’s last bar.

Jason Epstein, editorial director of Random House, invited Rosset to lunch a year ago. The two men have been friends ever since Epstein was a rising young star at Doubleday, and Rosset was with him the day Epstein resigned from his job. After a lunch with Barney Rosset, Epstein walked back to the office and quit because they wouldn’t let him publish Lolita. That week he and Rosset flew to London to try to convince Penguin Books to give them its American franchise. They failed.

Years later, when Grove needed help, Epstein persuaded his company’s business people to take over sales, marketing, and billing for Rosset’s house. As business partners they fought like crazy. “Barney’s a contentious man,” Epstein says. “He likes to sue people.”

But now that is in the past, too. And Epstein and Rosset were having their lunch on the Upper East Side last year. As Rosset remembers it, “We’re sitting there, and in walks Senator Moynihan. By himself. And he goes up to the bar and he’s reading this paperback book—all by himself.

“And Jason says, ‘Hey Pat, come on over here.’ I mean, I was impressed. And Moynihan came over and he sat down.

“And Jason said to him, ‘I want you to meet the greatest publisher of the 20th century.’

“Moynihan wants to be polite, and he says, ‘Oh yeah, I know.’

“Then Jason said, ‘No, I want you to know I mean it.’

“So,” Rosset says, finishing his story. “That was kind of nice.”

What Epstein saw in Barney Rosset was a publisher “who takes a lot of risks that look frivolous to many people, but there’s a serious radical impulse behind them all.

“He’s altered the climate of publishing to everybody’s advantage,” Epstein says.

What Rosset could not alter was the trend toward conglomeration and stratospheric advances. For years Rosset ran Grove Press on a shoestring, giving out paltry advances but allowing great experimentation. He simply published writers who caught his eye and ear. “Barney’s genius was to be in tune with the tenor of the times in a totally unself-conscious way,” his longtime friend and editor Fred Jordan, who remains at Grove under Weidenfeld and Getty, has observed. “In projecting what he liked, he happened to be directly on target. It’s so rare nowadays not to look first at what the market wants but to look primarily at what I want. It’s an extraordinary conceit, really.”

“Barney is like a spoiled child who’s had the chance to see a lot of his fantasies come true.”

Rosset always hired talented editors. In the early years, besides Jordan there was Richard Seaver, now head of Arcade Publishing, a subsidiary of Little, Brown. Later came Kent Carroll and John Oakes, both of whom now run their own small, independent houses. But in many ways Grove Press was a total creation of Barney Russet’s intelligence, sensibilities, and obsessions. He vented the forbidden impulses of his time, and in the process he altered the course of American publishing—maybe even American culture. He did it just by being Barney Rosset. As one writer who has been published by him points out, “I get the sense that he was never awed in the least by the great writers he dealt with. He served the ideals of art with no care for the commercial—but he never gave a damn about ‘art.’ ” Yet his impact was enormous. “Virtually every novelist and playwright today writes differently because of the books Grove published,” Fred Jordan says.

Rosset admits now to having “serious financial difficulties” at Blue Moon. When he was spotted at the American Booksellers Association convention in Washington this summer, he told one of the trade magazines, “I used to be able to publish exactly what I liked; now I publish what is available that I like.” With authors’ fees climbing exponentially, Rosset can hardly offer competitive advances. He says he wants to publish “today’s equivalents of Kerouac, Burroughs, Miller, and Rechy.” But as one writer points out, “Rosset was an impresario depending on a crop of fiercely individual and previously censored authors—all those authors who needed a champion, people willing to write without any guarantee of anything.”

Rosset will barely talk about publishing or his place in its history. He first wanted to produce films, and did—a moralistic movie called Strange Victory in 1948 that flopped. “I worked on it night and day for two years,” Rosset says. “And when it was over, I didn’t like it. I was very depressed. I thought, ‘You work on this fucking thing for two years and when it’s done—nothing.’ ”

I asked him if that’s why he became a publisher. “Yes,” he said. “I couldn’t face moviemaking after that. Books I stumbled into. It’s much more immediately gratifying. There are a lot of books. Not one every two years. While one is failing, you can be working on the next.”

Though he insists he can keep his publishing company afloat (he recently brought in some outside financing), there are some who think not, and are sad about it. A former associate at Grove said recently, “It’s not a question of personality. But Barney’s just not tied into what is happening now. There won’t be much to write about if you write what he’s doing now.”

“Barney is like a spoiled child,” a friend says of him. “He still acts like that. A child who’s had the chance to see a lot of his fantasies come true.”

At the moment, Rosset is working, childlike, through photo albums that he has pulled out of a storage closet. He has heaped them onto a glass coffee table in his high-ceilinged office/sitting room, a room lined with many of the books he has published and hung with canvases of abstract art and posters from Samuel Beckett’s plays. The publisher is kneeling on the floor beside the coffee table, and as he turns the pages of the albums, he points quickly to snapshots and says simply, in a high, quick voice, “That’s me.”

There he is in Hawaii on vacation with his Chicago banker father, a Jew, and his mother, who was Irish and Catholic. He was an only child and, he admits, quite spoiled. But from the beginning he was also a maverick, both within the social world of Chicago and even within his family.

He points to a picture of himself as a student in the ’30s at the Francis W. Parker School in Chicago, a place with no grades and an advanced curriculum. Rosset maintains that the best time of his life was his last year at Francis Parker. His classmate, the painter Joan Mitchell, who now lives in France, was a Chicago society girl who was married to Rosset for a short time after World War II. She once reminisced that “he ran his class” at Parker.

“Everybody looked up to him. He had a car before anyone else had a car, but that wasn’t it. He was shy and he didn’t talk well, and he became class president; and he was a little guy and skinny, with thick glasses, and he became the football star.”

When I asked Rosset how he’d developed his publishing taste he said simply, “I was a reader in high school.” Of his most famous find he is not much more specific or pretentious. “I read little dribs and drabs of [Beckett] in various magazine anthologies,” he remembers. “I read a few little things and I found it very amusing.”

Over the years Rosset and Beckett became friends, as Rosset has with many of his authors. “I thought that was the point,” he says. Rosset’s younger son is named after Beckett. Beckett once told a reporter, “Barney and I go to tennis matches, we play games and we talk politics. We don’t talk literature. It’s bad enough to write these books without talking about them too.”

Rosset is flipping through the photo albums. He turns to a page with a picture of his high school sweetheart. He stops. “That’s her,” he says. “That’s Nancy.” He goes to the closet and starts rummaging. Over his shoulder he says, “Anything that’s particularly important to me, I lose.”

In context it seems he means another picture album. But later Rosset talks about his love for Nancy and how she married his best friend at the Parker school. Though she has been dead for years, a young victim of cancer, he loves her still, or at least he loves what he remembers, just as he is in love with the Barney Rosset he remembers from then.

He comes back to the coffee table with what he’s been looking for—a jumble of white paper. It is the beginning of a biography of Rosset by a Chicago lawyer who worked on many of his court battles with the government. He shuffles through interview transcripts, through an outline of the biography—then finds what he’s looking for and hands it over. It is a short scene, a sex scene, between two teenagers. Rosset wrote it when he was young. He changed the boy’s name, but in the story the girl is called Nancy. The sex is mildly graphic, almost in the style of Blue Moon, but it is sex that is young and clumsy and ultimately not very satisfying.

“I can’t believe I knew that much about sex then,” Rosset says, taking back the manuscript. “I don’t think I know that much about sex now.” Though his sensibilities led him to Beckett and Jean Genet and Marguerite Duras, Barney Rosset himself often seems like a character out of Saul Bellow—Chicago-born, thirsty for life like Augie March, but grappling with his own scattered intelligence and obsessed with his women like Moses Herzog.

He came of age at a time when to be analyzed was commonplace among the educated denizens of Greenwich Village, and Rosset talks readily and openly about intimate matters: his dreams, his affairs, his wives, the lives of his children.

“I don’t dream about you anymore.”

Now, talking about Nancy gets him talking about Joan Mitchell, his first wife, of whom he says, “We should have never gotten married, just stayed good friends.” That leads him to Hannelore, his second wife, who originally worked at Grove as his assistant, and on to Christina, a ballet student who had been his baby-sitter and became his third wife. Then Rosset gets on the subject of Lisa, who started at Grove as a clerk and became managing editor and the fourth Mrs. Rosset. She left him a few years ago, and a legal divorce is in the works.

“My present wife,” Rosset says, and laughs. “Believe me, I like her—well, I don’t like her so much right now, because of a very simple thing.

“She said to me, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing. You should have taken the money—all this great money—and lived off it.’ As if I could have lived off it, clipping coupons….

“I said to her, ‘That’s impossible. I can’t do that. I don’t have anything. I have no pension. No nothing. No place to go. No no-thing. And I must try to take whatever resources I have and make whatever I can out of it. For better, for worse.’

“She said, ‘Ah, you’ve taken your money and squandered it. It’s a hobby.’ Like now, publishing Blue Moon Books—to her, she said, ‘That’s your hobby.’ ”

Rosset’s voice gets strident. “That made me very angry.” He pauses a moment and laughs. Soon he decides that he forgives her, almost. “In a way she was reaching for an insult,” Rosset says of his wife. “And she found it, like I did with Joan when I said, ‘I don’t dream about you anymore.’ ”

For Barney Rosset, that would be the ultimate insult. It was the worst thing he could think of to hurl at Joan Mitchell. If Rosset stops dreaming of someone that person has left his life. He still dreams of his Nancy from high school.

Rosset pulls himself out of a deep leather chair and starts once again looking for something he has lost. It is the Xerox of a letter he just wrote to Mitchell and expressed to her in France.

“Last weekend,” Rosset says, “after thinking about it for a long time, I called Joan and asked her for a loan—an honest-to-God loan. I wanted to borrow $50,000 from her and give it to her back immediately at $1,000 a month. And give her collateral for it—the limited edition of Beckett. All the copies that were left.

“I never got to it,” he says, finding the pages of Xerox among a heap of other papers. “I called her, and in the beginning she was very friendly and everything was fine. I called her to tell her that Beckett’s wife had died. Joan was very close to Sam Beckett through me. She didn’t seem interested. She was on edge about something.”

Finally, Rosset says, “She said, ‘How are you?’

“‘Ah, I have a problem.’ I said I’d like to borrow this money.

“She said, ‘What did you do with all your money? You wasted it all on call girls!’

“I said, ‘Joan, you know that’s not true and I don’t have any call girls.’

“She said, ‘I know that.’ Well, that was nice. She had the idea that one girlfriend I had was a call girl,” Rosset says.

“Whether that’s true or not,” he adds, “she wasn’t with me.”

A few nights after Mitchell refused him, Rosset went to one of the local bars that make up his New York world now and sat watching the Mets on television. Then he started scribbling a note to the artist on small pieces of paper. They soon became a thick little book. Strangely, he ran it through a copy machine before sending it. He is kneeling on the Oriental carpet now, trying to get the pages in correct order. As he passes the pages to me, Rosset says, “It’s right out of high school. It shows you how little I’ve changed.”

At the beginning of the letter Rosset had made a note: “Yeah,” it read, “written without call girls, without anybody. Just my memories and rum and Coke.”

It is rather early in the evening and Rosset has yet to move on from his martinis. He hands me the letter page by page and we read it together—he peering from his spot on the carpet. Much of what he wrote to Mitchell is too personal to repeat (even with his propensity to self-confession) or simply too personal to be intelligible. But at one point in the barroom letter, Barney Rosset reminded Mitchell, his high school classmate, that she had told him once that he had accomplished a lot in his 50 years since leaving Francis Parker. And that was worth something. Then, though the handwriting on the note is often difficult to read, there is clearly a reference to those decades in which Barney Rosset has put his considerable, manic, often obsessive energies into “publishing books.”

And, he wrote to Mitchell, scribbling in the dim Chelsea bar, half listening to the Mets game, “Some of which were not so bad.”

[Photo Via: Paper Nautilus Books]