Bellevue Hospital, on East 27th Street, has a staff of over 6,000 doctors, technicians, nurses and orderlies. The hospital’s medical facilities are among the best in the city. It boasts three emergency rooms and 134 out-patient clinics. The poison-control center is well known; the implantation unit, where doctors perform microsurgery to re-attach severed limbs, is renowned throughout the East Coast. For those who work in special areas like these, the days are as long and grueling as they’d be in any city hospital, but, for the most part, the work is straightforward.

One thing, however, sets Bellevue apart from the other New York hospitals. A large proportion of the people treated here are the city’s dispossessed and desperate—people with no insurance, no doctors, no foothold. They’re mental patients and homeless people looking for a place to sit or sleep (Bellevue tends to get the overflow from the numerous shelters in the area). In addition, there are prisoners from Rikers Island, or drug addicts suffering from AIDS, or a smaller number who, like Steven Smith, are looking to hide out, undisturbed. Spilling over from the emergency room into the prison and psychiatric wards, the patients fill the hospital with their misery and violence. The professionals who choose to work with them every day protect themselves as best they can, using everything from clinical detachment to raw humor to dogged optimism, turning the lurid into the commonplace, quietly going about their business. Here, then, are their voices.

A social worker: “I’m fond of the patients. It’s funny, no matter how bad your patients are, you become fond of them. Physically, too, you look at them and forget. You see patients that are really deformed—it’s amazing, you don’t see those things after a while. After about fifteen minutes, it’s not what you focus on. You start to focus on the person.”

A patient: “I work for an investment banker. I proved to my bosses that I’m OK. But I’ve been upset that my hair’s falling out. It’s my best feature. It used to be so curly. Oh? Oh, the bald spot, it’s well concealed. Maybe in passing I had been suicidal about my hair. You know, they carted me out in handcuffs! I want a formal apology. My life shouldn’t be interrupted. How could she say I’m irrational? If my parents got a message that I was at Bellevue, they’d lose it.”

A psychiatrist: “Don’t get caught up in that genius-madness stuff. It’s not fun to be sick. Bipolar disorders can be very painful. You suffer tremendously. I had one patient, he cashed in all his bank accounts to buy an airplane.”

A social worker: “I don’t take my work home with me; I wouldn’t be able to continue. But it would be hard to leave. There’s a vitality here, there are good people here, very bright, very exciting people. And the pathology we see!”

A social worker: “We have a transsexual on the unit. She requested an operation to remove her penis—she desperately wanted it—but they wouldn’t give it to her. Those operations are prohibitively expensive and I think they thought she wasn’t ready for it. So she chopped it off herself. With a razor. Here at Bellevue there’s an amazing implantation unit. I wonder if they put it back on [laughs]. Down in the ER the nurses like to say that if the male surgeons have a choice of body part, they always put the penis back on first.”

“Most of my patients are drug abusers. They have AIDS, AIDS-related complex. And that’s very scary. The patients we treat for drug abuse, they keep coming back.”

A social worker: “I stopped thinking that life is fair long ago. There are very few shocks at this point in my career. It feels like I’ve heard almost every story. I always say, ‘Don’t be afraid to tell me, I’ve probably heard it before.’”

A psychiatrist: “A lot of these guys wear gloves. It’s a masturbation ritual. They wear the glove on their right hand, to punish themselves. So they can’t do it.”

A psychiatrist: “I had a Rasta man in his mid-twenties. He was acting strangely, yelling. He had injured several police officers. He had even broken out of the restraints in his wheelchair. He was thrashing about, unable to give me a meaningful history. The police thought he was on angel dust. But I noticed that his skin was dry. So I gave him orange juice. Within minutes he was calm as a lamb. A diabetic.”

A social worker: “You have to trust your instincts. If it doesn’t feel right, you have to leave. You know there’s a potential for violence. The interview can always wait—you know that in the back of your mind. I never forget I’m in a psychiatric ward. [Laughs] [As] if I could really forget.”

A nurse, prison psychiatric ward: “One genius tried to break out last week. He thought, ‘I’ll drill my way out!’ He borrowed a nail clipper and started to dig into the ceiling. We found him with plaster on his head. He got up into the ceiling about an inch. He wanted Mayor La Guardia to come down and hear his case. Now we cut his nails for him.”

A psychiatrist: “It’s harder in the medical ER to pick up when they’re lying. In psych, it isn’t. There are patients that come here for asylum. It’s safe; they just come to lay low. Or they come in to rob the other patients. They could be wanted criminals. I usually can tell. I ask them to describe how they feel. Sometimes they trip themselves up. You see, it’s very difficult to fake being crazy. To be a good psychiatrist you have to have a dirty and suspicious mind. Don’t take anything at face value! Maybe they’ll say, ‘I hear the voices more in the left ear than in the right ear.’ Wrong! Maybe the patient will sleep through the night and eat a lot. Anyone who can sleep through the night here can’t be that badly off.”

A doctor: “I can’t remember anyone coming in with drug addictions [like the ones we see today] back in ’71. The dominating drug cases were related to Valium, overdoses, mostly prescription drugs. In the early Eighties there was a shift. It started with heroin and other narcotics like morphine. And sometimes we saw hallucinogens. People would come in very psychotic. One man arrived—he was using LSD, and he had a sort of auditory hallucination. The hallucination told him to look at the sun. So this guy looked directly at the sun, for hours. He went blind. His eyes were completely red, his pupils blank. A normal person would have immediately protected himself. Watch babies—if you take them from shade to sun, they immediately close their eyes. But when you’re on drugs you can’t protect yourself. It’s a different kind of violence, the LSD.”

An ER doctor: “Most of my patients are drug abusers. They have AIDS, AIDS-related complex. And that’s very scary. The patients we treat for drug abuse, they keep coming back. You treat them one week and then they’re back the next. I talk to them; I say, ‘I’m very angry with you.’ I tell them, ‘You know I worked very hard to save your life last week, and now you’re coming back and doing the same thing to me.’”

An ER doctor: “Many patients are not as intelligent as we think they are. They don’t think about drugs, shooting up, the way we’d like them to. It’s a reflection of the system, not the particular person. They feel they have nowhere to go, and simple family crises are resolved by taking drugs. Because that’s what they see their mother and father and brother do. You can’t blame the patients. Still, sometimes when I hear about AIDS, my position is referring to the larger realm of things. [AIDS] is probably the only way of getting rid of IV-drug abuse. I don’t think we’re doing it much better any other way. I know it’s a terrible thing to say, but it’s survival of the fittest. It’s justice. I have a biblical view of punishment. You see so many young people dying, you have to, in your mind, resolve it. The way to resolve it is to say they brought this upon themselves. It works for some of the AIDS patients but not the others. It [thinking in this way] is really the only way to handle this. This is nature’s way of handling things. There would be no end otherwise.”

An ER doctor: “Many of the IV abusers have tattoos. If you look closely, the landmarks of the tattoos are the landmarks of the veins. This way it serves two purposes—it covers up their track marks and it helps them to find the vein. They know just where to stick themselves. A big favorite is to have a picture of a woman with wavy hair. Her tresses run right along the line of the veins. Another favorite is crosses; they shoot right in the center. I’m sure Jesus would love that.”

An ER doctor: “In the early Eighties they were talking about ‘gay-related complex.’ We saw a lot of rashes—elaborate ones that covered the whole skin. Kaposi’s. Actually AIDS was diagnosed through Kaposi’s sarcoma, which is a skin lesion. We were looking for that, for the lymphadenopathy, enlarged lymph nodes. I would diagnose at least two to three patients a week. Diffuse lymphadenopathy, for investigation, cause unknown.”

An ER doctor: “So many patients who were gay, they had this disease. We didn’t know it would be so transmissible. I remember in ’81 we did resuscitation without gloves. When a patient would show up in the trauma slot, a car accident, a young person without pressure, clinically dead, and you wanted to resuscitate them, you didn’t have time to put on gloves. You just took a knife, cracked open the chest, opened the ribs and started massaging the heart. It took years to grasp the danger.”

An ER doctor: “The issue is really the gloves. In ’83 we started using them. I felt very uncomfortable, like my patients would think I thought they were dirty. I really resisted it. I always shake hands with my patients. Someone once came to me and said, ‘You never know where that hand was before.’”

An ER doctor: “One time, only once, I refused to shake hands with a patient. I always shake hands. This was a patient I’ll never forget. He was a prisoner. Most of the time guys come in with one or two guards. He had ten cops buzzing around him. A real heavy hitter. I make it my practice not to ask why patients are arrested, so I didn’t. This guy had swallowed packages of heroin, right when he was arrested. I had to remove them from his stomach. I lavaged him for two hours. It was very difficult. You put a big tube down into the stomach and irrigate it with saline. And then I gave him X-rays and blood tests. When it was all over, the cops asked me to sign his release from the ER. While I was writing it, they said, ‘You know what? This guy just murdered his girlfriend. She was sixteen or seventeen years old and he just slashed her throat.’ I thought, Oh my God. Afterward, when I went back in to disconnect the IV, he didn’t know I knew. He put out his hand for me to shake it. I looked at his hands for a moment. I thought, These hands just murdered a sixteen-year-old. I said, ‘I can’t shake hands with you.’”

A triage nurse: “Occasionally a patient takes off. Within twenty-four hours, they’re back. Usually, they hang out in the lobby. Or they go see their mother.”

“It’s good to be religious, because in a way you accept things. You know that’s it; you have no choice.”

An ER doctor: “I had a male prostitute, a walk-in. He was definitely HIV positive. [Prostitution] was his livelihood. He had contacts with at least twenty men and he never told them. I called risk management, I called the social work department. I said, ‘We have to do something. I have a male prostitute infecting men.’ They said, ‘You can’t tell any of these men. You can’t inform his contacts.’ He just left. It’s so scary.”

A doctor: “Some patients I never forget. I had a very religious Jewish family; they had seven children. The eighth child had a minor operation at birth. She was transfused and got AIDS. When I saw her in the emergency room she was one year old. Let me tell you, her face was something you never forget. She looked me straight in the eye. She comprehended. This baby knew she was going to die. Her family felt it was a punishment from God. It’s good to be religious, because in a way you accept things. You know that’s it; you have no choice.”

An ER doctor: “There was a girl who had the tips of all her fingers severed by a bread sheer. Four of her tops chopped off except her thumb. She was conscious, so she was crying. A young woman in her twenties. What can you say? It was a terrible loss. They weren’t really implantable; they were too short. Still, you can’t fully predict what the outcome will be. I always say that to the patient. Maybe it will be better. Maybe it will change.”

A doctor: “I prefer to work at Bellevue. I like the population. Many patients—you’re their last resort. You’re in a position to have an impact on their lives. At NYU you see patients who are wealthy, who have a private doctor. Here you can make life and death decisions and you can do a lot of good.”

A resident: “Feet are a big subject. Especially in the winter. Diabetics lose toes from lack of circulation. A lot of the alcoholics lose toes. I had one guy last week without all five toes on one foot. He had gangrene. I said, ‘It took you a while to have someone look at that.’ ‘Yeah,’ he said. I didn’t notice anything was wrong.’”

An ER doctor: “We never have enough beds. Patients wait here for days; that’s the real tragedy. One day there was a very young patient, a homosexual man with AIDS. His mother came in with him. The patient was basically dying. I told her, I have no beds, why not take him to another hospital? She said no other hospital will take him. She pulled me aside, she said, ‘Please take him, I just want him to die here. I don’t want him to die at home. I don’t want him dying in my arms.’”

An ER nurse: “I had a new nurse, a green one. I was handling her. I said, check out the blister down the hall. She was gone ten minutes, then came back pale as a sheet. Turns out he was a transsexual, IV-drug user, suicidal amputee. So much for the blister.”

A social worker: “When I started here, the first piece of advice I got was ‘Never turn your back.’ I always position myself very carefully when I’m dealing with agitated patients. I sit close to the door. I never close the door when we’re alone in a room. It all becomes second nature. Survival instincts.”

“I sort of believe in fate. Everybody has his own, and when it’s supposed to, it will hit. You know you’re just as likely to be killed on the subway as you are in the hospital.”

An ER doctor: “If I’m uncomfortable with a patient, I keep the door open. If the patient is a prisoner, I ask the arresting officer to be in the room. But you can’t see behind you. You can’t know what’s going to hurt you. That’s the risk you have to take.”

An ER psychiatrist: “People have begun to feel the hospital is not a safe place. What is criminal illness? Is it an illness if someone hurts someone? ‘I’m crazy.’ Is that an excuse? One time I was interviewing a man. He insisted he had to be admitted. I said, ‘I understand you want to, but why do you have to?’ He pulled out a knife. ‘Now do you understand?’ he asked. I figured, I’m cool, I can handle this. I moved my leg to press the safely button under my desk. I thought he pulled the knife for bravado, to make his point. But he grabbed my leg so I couldn’t push the button. Whooah! He’s been here before, he knows the routine. I ran out of the room. Now I know, no one should be a hero. I’m not going to be Super Doctor. Now I take stock. If I get the willies, I stay away.”

Scene: the psychiatric ward. Jimmy, a gaunt, friendly man, traipses around, offering cookies to all.

Jimmy: “How’s the space program going? Good, I’m glad it’s going well. When I came in here I was really out on a bird. I wanted to find this woman; I wanted to marry her. I thought if she saw me naked she would. Did I finish high school? No. I only went through the seventh millennium.”

His psychiatrist [looking over at him]: “On Sunday he came in. The police had him. He was walking around completely naked, screaming, spitting. Very belligerent. Very weird. Do you have a chart on Jimmy Lewis?”

Nurse: “Jimmy Lewis? We have him as Frank Davis. That’s who he was last night.”

Jimmy: “What do you think of green money as opposed to blue money? WHAT IS BLUE MONEY? The government is losing track of the green money. So they’re taking all of it off the market. We’re going to have blue money now. The government will be in control.”

Bellevue Hospital celebrates its 255th anniversary in March. Over the course of 1990, the hospital will have served 476,000 patients.

Sidebar:

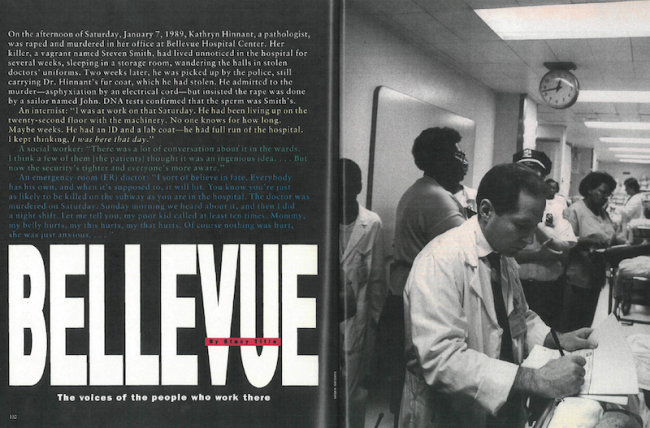

On the afternoon of Saturday, January 7, 1989, Kathryn Hinnant, a pathologist, was raped and murdered in her office at Bellevue Hospital Center. Her killer, a vagrant named Steven Smith, had lived unnoticed in the hospital for several weeks, sleeping in a storage room, wandering the halls in stolen doctors’ uniforms. Two weeks later, he was picked up by the police, still carrying Dr. Hinnant’s fur coat, which he had stolen. He admitted to the murder—asphyxiation by an electrical cord—but insisted the rape was done by a sailor named John. DNA tests confirmed that the sperm was Smith’s.

An internist: “I was at work on that Saturday. He had been living up on the twenty-second floor with the machinery. No one knows for how long. Maybe weeks. He had an ID and a lab coat—he had full run of the hospital. I kept thinking, I was here that day.”

A social worker: “There was a lot of conversation about it in the wards. I think a few of them [the patients] thought it was an ingenious idea….But now the security’s tighter and everyone’s more aware.”

An emergency-room (ER) doctor: “I sort of believe in fate. Everybody has his own, and when it’s supposed to, it will hit. You know you’re just as likely to be killed on the subway as you are in the hospital. The doctor was murdered on Saturday. Sunday morning we heard about it, and then I did a night shift. Let me tell you, my poor kid called at least ten times. Mommy, my belly hurts, my this hurts, my that hurts. Of course nothing was hurt, she was just anxious….”

THE PSYCHIATRIC WARDS

“He’s very organic,” says a social worker of a patient as she gives an informal tour of the wards. “Organic” is an idiom for a patient whose state is near vegetable. The man she’s referring to is belted into his seat. Slumped, expressionless, the man watches Hawaii Five-O on TV. Three of the other patients on this cheerfully painted (orange and yellow) psychiatric ward pace. Up and back, frantically—purposefully. Asked his destination, one says, “I need paper towels”; another, “a Giants game.” “Where am I?” an older, unkempt man asks suddenly. “New York City,” says his psychiatrist. “Really,” the man says, bewildered. “New York never looked like this before.” On the opposite side of the hall are the psychiatric and medical wards for prisoners. Between two security doors sits a guard. There’s also a sandbox, a repository for the cops’ unused bullets, since this is where the officers unload and load their arms. Above it, a sign: NO FIREARMS OR AMMO. The wall opposite has a police poster that reads, PRIDE SPIRIT EXCELLENCE; a very bored police officer sits below it, doing a puzzle.

“We’ve got your basic stuff here,” says a prison supervisor. “Homicidal, schizophrenic, suicidal. On the hospital side there’s a different ambience—once in a while you’ll get your AIDS dementia case—but basically over there it’s pretty calm. We keep the psych patients and the hospital patients apart. Some yak runs over to the hospital-care side and pulls out IV’s—that’s all I need.” Two floors above the prisoners is the adolescent psychiatric ward. Some of the kids sit in their rooms, quietly looking at the blank walls. Others want to have sex. “It’s a challenge keeping them apart,” says the social worker on the hall. “They know how to do these things.”

Over in another adult psychiatric ward, the women are getting excited. They’re off to the patient beauty parlor. One wants a tease; another, a manicure. Still, Tutti, Eve and Deb won’t be completely satisfied until they convince Henry, a large, taciturn man, to come with them. “You can get your nails buffed,” exclaims Tutti. Tutti begins to punch his arm. “C’mon.” Smack. “C’mon.” Smack. “Hey,” screams the orderly, “he’s no fag. Leave him be.” The three women look disappointed. “C’mon,” says Tutti, and they head off to the beautician.

THE EMERGENCY ROOM INTERVIEW

“What seems to be the problem?” the doctor asks the frail woman who’s slouching on the edge of a gurney. “I thought I was going to die tonight.” “Why?” “I smoked crack.” The doctor turns the young woman’s wrist. “Have you used heroin?” “Yeah.” “Do you have any children?” “Yeah, “You have custody?” “No, my mother does.” A pause. The doctor looks down at her chart. “Have you had any abortions?” “Yeah, two.” “Have you been tested for AIDS?” “Yeah, I have AIDS, for two years.” The doctor puts a stethoscope to her heart. “What are these?” he asks, pointing to the scars. “I had open-heart surgery.” “An infection?” “Yeah. [IV-drug abusers, with each injection of the chosen drug, also inject themselves with bacteria. Many of these bacteria lead to endocarditis, an infection of the heart that destroys the valves.] I had open-heart surgery for a valve replacement.” “How long have you used drugs?” The woman looks down at the dried blood on her legs. “Since my little girl was a baby. I shot heroin and coke together.” “Why did you start?” “I figured, if I shoot drugs, he’ll get away from me.” “Have you ever been suicidal?” (The ER doctor has to decide where to send the patient: to psych or the hospital proper. Sometimes it’s hard to make that decision.) “Yeah, when I found out I had AIDS.” “How did you buy drugs?” “From 3 friend upstairs. I spend my Social Security check. Then I get my friends to give me money.” “Where do you live?” (During the interview the doctor is taking the pulse, checking reflexes, methodically working over the patient.) “I live at a hotel in the East Twenties. Some people smoke, some snort—hard to stay away when you live in a place like that.” “Have you ever been a prostitute?” “No. Just a dancer, or a stripper. In ninth grade I got pregnant and stayed home.” DIAGNOSIS: The interviewing doctor believes that the patient will die of heart complications before she dies of AIDS. She will be admitted to the hospital.

THE EMERGENCY ROOM

A young, misshapen woman named Dawn slogs along the length of the ER. She’s a “sickler”—she suffers from sickle-cell anemia—so she drags an IV alongside her frighteningly skinny legs, clad in purple Lycra pants. “I’m in pain,” she wails. “I’m in pain!” As she tools around the room, she passes the same people once every minute or so. “I’m in pain!” she wails again. “Give me a shot!” The doctor shrugs. He knows that, like most sicklers, she’s become addicted to the painkiller he originally put her on for the disease. But as usual, this morning the ER is noisy, teeming—with patients on gurneys waiting for beds, other addicts kicking the walls for painkillers, a newly arrested man convulsing from a speedball overdose.

She begins to whine. “I’m sorry. Dawn,” the doctor shouts, “but you’re not my only patient.” A convict from Rikers gets wheeled in, with a mangled, infected leg. The doctor asks the nurse to take his temperature. “Orally?” she asks hopefully. “No,” says the doctor, “he might be trying to fake it. I want an accurate reading.” But the large, black man with a surgical pin in his leg is not faking it. It seems the pins have pus oozing out around them, and the infection has sent his temperature up to 102. Still, he’s cuffed, right arm, left leg to the stretcher. The captain escorting him just laughs. “We need those,” he says. “I had a guy in a wheelchair for five years. As soon as they left him alone, he jumped up and ran like a thief.” “I’m in pain,” interrupts Dawn, sobbing. “Give me my medicine.” Then she continues her quest for relief.

An older Chinese woman in a green and fuchsia housecoat is wheeled in from the ambulance port. She’s describing her ailment in high-pitched Cantonese and with wild gesticulation. No one speaks her language. The triage nurse uses the computer to track down someone who does. Luckily, a Chinese resident is upstairs. Dawn finally gets her shot. “Thank you,” she says sarcastically. “No. Thank you,” grumbles the doctor. He knows now she’ll shut up.

[Photo Credit: Bags]