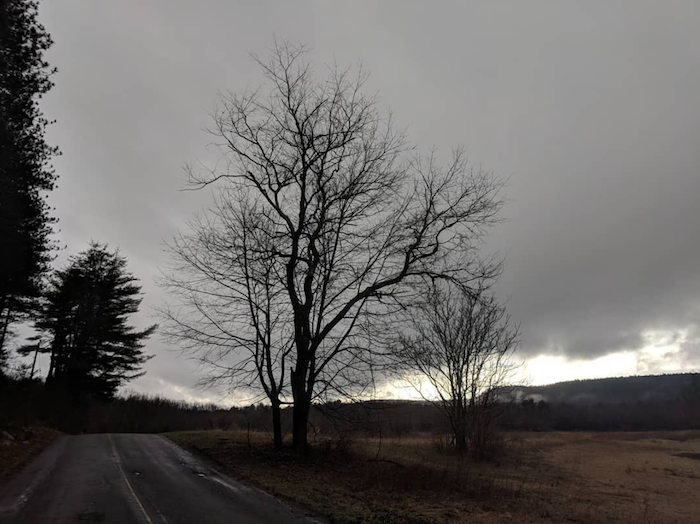

He steers the van over the rolling folds of county Route 579, a two-lane road flanked by fields once neatly tilled and sown, now increasingly given over to development. But the landscape still carries the flavor of open country in the deep dead of night. His headlights find the sign for Woolf Road, and he turns down a curving, narrow lane; here the trees lean in close on both sides. A half mile later, he takes another left and creeps down a blind driveway, curling right, until his beams alight on an incongruous sight in the wooded blackness: two ornate white gates. Sculpted lions perch atop the columns that anchor them. The letter J is patterned into the gate on the left, a W into the other. Between the gates stands a brick wall. Set into the brick is a plaque. From a distance, it looks like a Hall of Fame plaque, Cooperstown bronze, but this plaque is slightly different. It depicts a man’s head and shrugging shoulders, his hands held out, palms up, as if to say, Who knew? And these are the very words printed below: WHO KNEW? ESTATES.

The gate on the right swings open, and Gus Christofi steers the van past the expressionless gaze of the lions, down another driveway, and slows at the house, 31,000 square feet of star shrine, the centerpiece of a sprawling fiefdom that shoves the Jersey woods aside. It is a building quite unlike anything Gus has ever seen.

Who knew, indeed? That he’d ever arrive at such a place? That a man who’d busted into other peoples’ homes in search of things to fence would ever see such a door as this, unlocked, welcoming him in? That a man who had shuttled for so many years from jail cell to jail cell would one day come face-to-face with such an ornate and pearly gate?

Then again, who knew how false the facade would turn out to be? How slick an Oz-land stage set could look? As Gus strolls toward Jayson Williams’s front door, he doesn’t see it, not for what it really is: a gateway back into a world he’s spent seven years desperately trying to escape.

The funny thing, the surprising thing, is how much they have in common, at least at first glance. Jayson hails from the Lower East Side of Manhattan—a cocky kid who hung with “a bunch of Italian tough guys,” who did jail time as a teen for hitting a cop, who muddied his life with alcohol. Gus was raised across the Hudson River on the dark streets of Paterson, New Jersey. He dropped out of school after sixth grade, ran with a bad crowd, spiraled into addiction by the age of 16.

Both had reclaimed their lives. Both had realized their promise. And now both had moved on to a most unfamiliar landscape—the woods and horse fields of northwestern New Jersey—Gus, at 55, seeking a clean and sober place, Jayson, at 33, in search of a clean escape.

When you think of all the ways their paths could have crossed, it’s remarkable that they were as yet unacquainted. They easily could have met on the back roads of Hunterdon County—Gus driving his limo, Jayson piloting his new motorcycle, the one with the absurdly large engine. They might have met in a sports bar when their drinking days had overlapped. Or on the set of the United Way commercial that featured Gus telling the tale of his recovery, filmed on the leafy grounds of his rehab center.

And yet, given how much Gus loved his work and given how much Jayson loved a good time, it only stood to reason that they’d meet this way. On this night. When Gus was on the job. And Jayson was throwing a party.

It’s Jayson’s brother who makes the call to the dispatcher at Seventy Eight Limousine on the evening of February 13: He hires a car to pick up several people just over the Pennsylvania state line in Bethlehem, where the Harlem Globetrotters are playing a charity game at Lehigh University. Jayson will be at the game with some friends. He has invited the Globetrotters to join him for dinner. They’ll need a limo ride to the restaurant.

In his prime, he was a force on the court; off it he took to the limelight with ease, feeding a public ever hungry for over-the-top behavior.

A few minutes later, Gus returns to the office. His workday has officially ended, but he leaps at the Williams job when the dispatcher offers it. Gus is a serious sports fan, and Gus is a workaholic, and Gus deserves to catch a break. He’ll reel in a considerable tip on top of $65 per hour. He’ll get to meet the local All-Star.

Sam Nenna, the owner of Seventy Eight Limousine, clears Gus’s schedule for the next day. Nenna figures this will be a long night. Jayson has used the services of Seventy Eight Limousine before, for trips to the casinos in Atlantic City. No telling when Gus’s evening will end. It doesn’t begin until 10:30, when he steers the company’s silver van to the Comfort Suites in Bethlehem to collect four Globetrotters: two former Nets, Benoit Benjamin and Chris Morris, and two men Jayson has never met, Curley Johnson and Paul Gaffney.

Jayson will drive his own car. In all, there will be thirteen for dinner, and on this night they’ll be treated to first class. The best food. The best company. Jayson’s old friends Benjamin and Morris will meet his new ones, Kent Culuko, 29, a former Jersey prep star, and John Gordnick, 44, a middle-school basketball coach. The star of the evening, of course, will be Jayson. Center stage is a place in which he has long been comfortable. In his prime, he was a force on the court; off it he took to the limelight with ease, feeding a public ever hungry for over-the-top behavior. His best-selling memoir, Loose Balls, paints a portrait of a man who has spent his entire life gleefully Bigfooting all convention, demanding respect at every turn, dispensing frontier justice to anyone foolish enough to defy him, desperate to prove his manhood by whatever display necessary.

Two years ago, a series of playing injuries pulled him off the hardwood stage. Since then he’s had little trouble finding other outlets for his act: MTV. The game-day studio at NBC. The taverns in and around his new neighborhood. Even the sprawling grounds of Jayson’s estate are not vast enough to rein him in.

A man spends more than half his life imprisoned by addiction, supporting his own demands in the company of no one but himself—well, when he’s freed from those bonds it stands to reason he would want to make amends. And so Gus Christofi has decided to dedicate his life—as sappy as it sounds—to helping others. He makes up for the years in solitude by embracing everyone around him. The photographs are legion: Gus, the stout figure with the fold-lined face of a bulldog who has long given up the fight, his arm draped around this guy, that guy, a buddy’s kid; he’s like Zelig—someone takes a picture, Gus is in it. He is driven, it seems, to weave himself into the fabric of society. Determined to make things easier for the retired pharmaceutical executive who insists on Gus as his driver and for the homeless guy on the streets of Manhattan, hitting up goodhearted Gus with a goofy scam. Gus can’t pass a stranded motorist, even on a busy interstate, without tapping the brakes, whether it’s a day laborer in a broken-down beater or a state senator on his knees, struggling to fix a flat.

Gus’s fares will testify to the depths of his new soul. Along with the recovering addicts he counsels at Freedom House, they provide the simple joys in a life now measured in small blessings. He smothers them with attention: bags of their favorite candy stowed in the trunk, jokes, card tricks he learned in jail. If he drives someone to the medical center to visit a sick relative, a card arrives in the fare’s mail a few days later. From Gus. Hoping everything turned out for the best.

He doesn’t do it for profit. He does it because he likes people. And people invariably like him. By the time he has chauffeured the Globetrotters to the Mountain View Chalet in Asbury, they are so charmed that one invites him in.

The Mountain View rings high-class for a restaurant hard by the asphalt of I-78. Behind the Mountain View’s doors, diners enjoy an evening of rural upscale: $20 entrees. Haute cuisine sauces. Etched-glass partitions.

During the next few hours, according to one source, the Wlilliams party will run up a tab of $1,800. Gus sits to the side, drinking coffee. According to one account of the evening, though, he is not entirely excluded from the revelry, for at one point Jayson says something to Gus, something sealed away in court files, an off-hand remark with a nasty overtone.

Cryan’s is a lousy place for an angry soul to find himself late on a Wednesday night.

Gus lets it wash over him. He does not have a violent streak. Even as a kid, he shied away from fights. Maybe in the young and troubled Jayson he sees something of his former self as well.

The barb does not surprise anyone who knows Jayson, knows of the hair-trigger temper, the trip wire tied to the volatile influence of alcohol. The catalog of Jayson’s early-career explosions is substantial: a 4 A.M. street fight after a playoff game; two men maced, another one beaten outside the bar Jayson had bought in Manhattan; a busted head in Chicago; a tag-team melee with Charles Barkley. “Part-time player, full-time party animal” is how Rick Barry put it once to an acquaintance, who passed his words on to Jayson, who promptly took it out on Barry’s son. Roughed the kid up for four full quarters. Knocked him down. Cross-wired justice, the Jayson Williams way.

These days, in Hunterdon County, just about anyone you meet will furnish a tale about Jayson’s antics, though none are as outlandish as the anecdotes in Loose Balls. The story about the kid Jayson knocked out, then tried to shove from a fourth-story window in high school. The one about his father planting a bullet in the posterior of a boy who had given his son trouble—the father whose license-plate holder carried the legend .45 MAGNUM, reflecting the caliber of the weapon he routinely carried. Those of us searching for clues to Jayson’s behavior need only look at the picture his memoir sketches of his childhood years in New York and South Carolina: the day one brother shot another. The day his mother shot at his father after she’d been told he was cheating on her. The day his half sister was brutally attacked. The day she learned the hospital blood transfusion had given her HIV. The day she passed it on to another sister through a shared needle. Both sisters died. Jayson was only a rookie when he adopted a son and a daughter left behind by his sisters. As Jayson tells it, after the man who’d beaten his sister was released from prison, Jayson hunted him down. Wanted to kill him. But let him go.

Some of the stories in the book reek of hyperbole. On this night, though, there’s a very real court appearance awaiting Jayson, the result of an incident three months ago at a suburban tavern favored by softball teams, local professionals, bikers and laborers. A clean, well-lit venue offering a glut of TVs and every Irish beer on the market. Cryan’s is a lousy place for an angry soul to find himself late on a Wednesday night. A man who saw Jayson at the bar recalls, “He was pretty tuned up. He’d had a few.” Some kids started taunting the washed-up All-Star, says the witness, and Jayson took the bait. He lunged. Got himself into a scuffle. Ended up in cuffs. The Branchburg Police Department charged him with obstructing its investigation by twice shoving a policeman.

The incident did not appear to trouble Jayson’s employer, NBC, which, in the fashion of so many of his employers through the years, felt no need to put undue emphasis on his transgressions. If this is the history of a man constantly flirting with disaster, crying out for help, it is also the story of a man favored by constant forgiveness.

One of the reasons he built his own well-appointed theme park, said an allegedly older and wiser Jayson in his memoir, was his desire to protect the outside world when he felt the need to go a little crazy. And so on this evening, when dinner at the Mountain View ends, close to 2 A.M., Jayson decides to move the party to his place. The Globetrotters beg off. But Jayson insists. He will drive them himself. Gus will transport the others in his van. For what good is a trophy house when there’s no one there to see it?

The hallways run for half a football field. The walls harbor a basketball court, a theater, a billiards room and an indoor pool. A columned balcony overlooks the outdoor pool, two par-3 golf holes and a sweeping vista of landscaped real estate. Tucked away on the 130-acre grounds are a duck pond, riding stables, an ATV track and a pasture with a gated entrance, also decorated with the initials JW, for his prize cattle, which graze in its shade.

When Gus’s van reaches the end of the driveway, it’s Jayson’s friend Kent Culuko who invites him into the house. Gus grabs his camera. For a man whose home is a small apartment shared with a fellow recovering addict, the sheer size of the place is incomprehensible. It almost feels cold. But the grand scale is also revealing, a physical manifestation of the owner’s need to appear larger than life.

The truth is, Gus’s apartment is a whole lot more comfy. It’s on the ground floor of an anonymous two-unit home eighteen miles north, in a dull western New Jersey town bruised by the passage of time. The furnishings in Gus’s place pale compared to the expensive appointments in Jayson’s place, but they reflect the soul of the man. The mirror, for instance, that Gus salvaged from a dumpster. It took him months to restore. He placed his picture on it, then wrote a poem, “The Man in the Mirror,” because he, too, had been reclaimed, through the efforts of an army of folk: the counselors at Freedom House, his probation officer, his best friend, Joe Armstrong—all had helped salvage and polish the person you see today.

Joe lives on the second floor. He volunteers as a counselor at Freedom House, too. Together he and Gus received the rehab center’s achievement award in 1999. Joe used to give Gus grief about the mirror. Spare me the sentimental stuff, he would tell Gus. Gus would call Joe a cynic. Joe would call Gus a sap. So when Gus wanted to play for Joe the audiotape he’d made on Christmas morning, 1999, Joe said no. No sentimental shit. But Gus made him listen to it anyway. Something had come over him, a moment of clarity, and Gus had to get it on the record. He spoke from the heart while sitting at the kitchen table, with a gospel version of “Silent Night” in the background as a syrupy sound track.

“Almost five years ago, around this time, I was released from Middlesex County Jail,” Gus says. There’s some gravel to his disembodied voice. Some world-weariness, too, but it’s not confessional. It is a matter-of-fact recitation.

“I weighed about 170 pounds and had about half a garbage bag of clothes. I wanted to change the way I had lived for the past forty years. I was 47 years old, no direction, no clue how to live a sober, meaningful life. No true friends to speak of. I was lost, alone and scared I was going to die.

“I used to think about all the things other people had,” says the voice on the tape. “But now I choose to speak of the things for which I am grateful.” And one by one, he lists them: his sobriety. His God. His job. The family members who are back in his life. His friends.

“There are too many things to list,” says the voice. “It would take ten sheets of paper.”

If he’d made that tape today, Gus may have added one more thing: the credit card he had finally obtained. The first he ever owned. It was one of the proudest moments of his life, proof of his new standing in society.

Jayson had had something of an epiphany himself a few years earlier, after another NBA star and St. John’s alumnus, Chris Mullin, explained the economics of sobriety. Mullin told Jayson he had decided to give up drinking. If I stick with alcohol, he said, I’ll end up back on the streets with nothing to show for my work. If I sober up, it’ll translate into nearly $30 million over ten years. With a return like that, why not put the high life on hold for at least a decade?

These figures, this logic, they intrigued Jayson, a man forever obsessed with money. How much he had. How much others had. So he cut back on the party scene. Even suggested inserting a no-alcohol clause into his 1996 contract. No more public scandals. No more tipsy brawls.

This late-night tableau is by now replete with all the makings of a Jayson Williams theatrical performance: alcohol, money, attitude.

Smarter, soberer, more mature, Jayson became a near great player, the best rebounder in the NBA. He was selected to the Eastern Conference All-Star team. The year his Nets made the play-offs; this was when all the promise was finally fulfilled. The Nets rewarded Jayson with an astounding $86 million contract, which spawned an estate measured by equally astounding numbers: more than $100,000 a year in property taxes. Proof that a former outlaw can be made clean and shiny and new.

As the guided tour of Who Knew stretches into the early-morning hours, Jayson’s blood alcohol level, according to a source close to the investigation, is conservatively estimated at .19. He is animated. Witnesses say that at one point he bares his torso to show off how buff he is; at another, for the second time that evening, he addresses Gus. Puts him down. Half good-naturedly.

Why Gus? Maybe because he’s neither a player nor a groupie. Maybe because he’s the clear-cut comic foil in this late-night tableau, which is by now replete with all the makings of a Jayson Williams theatrical performance: alcohol, money, attitude. The only thing missing is a gun—the most obvious manifestation of a man’s need to prove his manhood.

Tales of athletes and firearms are hardly unusual in this day and time, but there’s nothing routine about Jayson’s love of guns, not if one anecdote in his book is grounded in any semblance of truth. The scene was an after-hours gathering at Manute Bol’s home. Jayson and his buddy Franco were drinking with Bol and his uncle from the Sudan. Fueled by a couple of Heinekens, Bol’s uncle started giving Jayson a hard time. “You the one they call Mr. Capone? You not so tough.” When Bol’s uncle donned a necklace of crow feet, rooster feet and turtle heads to prove that Jayson’s tough-guy act was no match for his charms, they all had a good laugh. But Bol’s uncle kept pushing. It was around 3 A.M. when Jayson fetched a pistol from his BMW, pointed it at Bol’s uncle and scared the man half to death.

These days Jayson’s tastes run toward shotguns. He shoots skeet, as if he has tamed his family’s legacy of Wild West shoot-outs. Turned his frontier sensibility into a rich man’s game. Truth be told, though, he nearly blew New York Jets receiver Wayne Chrebet’s head off by accident once, not the kind of gunmanship a hunt club looks for in a man.

In fact, it’s remarkable that Jayson is permitted to own guns, considering the night in 1994 when he was charged with reckless endangerment and unlawful possession of a weapon in the parking lot outside the Nets’ arena. Prosecutor John Fahy claims Jayson fired a SIG Sauer .40-caliber automatic pistol over the heads of teammates. Jayson says he never fired the gun. No one was hurt. Over Fahy’s vigorous objections, the judge dropped the charges after Jayson agreed to enter a pretrial program and to spend a year lecturing children about the dangers of guns. As part of his rehabilitation, he purchased newspaper ads in the Bergen Record. “Shoot for the top. Shoot for your future. Shoot Baskets, not Guns.”

The rack on the wall in Jayson’s enormous bedroom holds several shotguns. It is one of the first things Gus sees when he enters the room between 2:30 and 3 A.M. along with Jayson and three Globetrotters. Gus does not have to know that some of the guns are loaded to feel uneasy; he hates all guns. He has hated them since his father tried to teach him to hunt as a child. Back then Gus would not touch his father’s shotgun. Even the replica pistols his friend Joe used to collect gave him the creeps.

According to witness accounts, evidence at the scene and sources close to the investigation, this is what happens next: With Culuko in the doorway behind him, Williams opens the glass case—which is unlocked—and takes out a twelve-gauge double-barreled Browning shotgun. He cracks the gun open, lowers the barrel and peers inside. Turning toward Gus, who stands three feet away, he flicks the gun shut with a snap of his wrist. The moment the barrel clicks into place, the shotgun discharges. All twelve pellets enter the left side of Gus’s chest. They open a hole large enough to swallow a silver dollar. Gus Christofi falls, coming to rest on the floor on his left side. The life bleeds out of him, a good life, fifty-five years in the making and a few minutes in the ending.

It is not likely that he is conscious after the pellets tear into his chest. It is not likely he is able to reflect on the profound and futile and sorry unfairness of it all: that seven years spent fleeing his previous life led him back to a world worse than any he’d left: That there are some sins for which you never stop paying.

According to witness accounts, the blast awakens Jayson’s half brother, who rushes in from a distant bedroom. John Gordnick comes from the downstairs gym, where he was playing ball with his two young sons. Williams and Culuko confer. Culuko instructs the witnesses to tell the police it was a suicide. Jayson wipes down the gun. And then he takes the hand of Gus’s dead body, still warm, and tries to imprint Gus’s fingerprints on the stock.

Jayson takes off his clothes and tosses them to Gordnick to dispose of before the police arrive. He goes downstairs and dives into the pool to wash himself clean, wipe away any trace of what he has done, and when his body emerges, six feet ten inches of finely tuned athlete, it glistens, free of all sin—renewed, restored, absolved. He drapes it in a fresh set of clothes and awaits the arrival of the authorities. He will plead innocent to seven charges, including aggravated manslaughter, a crime that carries a penalty of ten to thirty years in prison.

On February 20, Gus Christon’s body is lowered into the ground, accompanied by Joe Armstrong’s seven-year-sobriety medallion. Gus himself didn’t make it to seven. But perhaps in death he will right one more life, the life of Jayson Williams, as Jayson sits and ponders his misdeeds, maybe in a jail cell, a cell Gus used to call home. Who knew?

[Photo Credit: Peter Richmond]