“You want to see it?” Emilio Emini offers to show me the enzyme on which he bet 10 years of his virology career and a billion dollars of his company’s money. Rising from his desk, Emini, who is tall, dark and hairy—and a little too big for his office at the suburban Philadelphia research campus of Merck, America’s largest drug company—reaches over into a folder and hands me a single photographic slide. I hold it up toward the window, trying to catch the light of a dreary day.

The enzyme pops bright blue off the slide’s black background. This is the HIV protease. It is the single most important molecule in all of AIDS. The drugs that were built to stop this enzyme from working, the “protease inhibitors,” have, in the past year and a half, dramatically changed nearly every aspect of AIDS treatment.

At first glance, the protease (pronounced PRO-tee-ace) looks like a schematic drawing of a bug’s head, with two pincers protecting the mouth cavity. Those pincers are the key to what the protease does. When HIV is reproducing itself, it grows new strands of proteins, which the protease helps birth by chemically biting them off. A protease inhibitor is like a rock that gets jammed into the bug’s open mouth, preventing the pincers from closing and, ultimately, HIV from replicating.

Others have described the protease as looking like two fists, knuckle-to-knuckle, thumbs peaked at the top. I ask Emini for his interpretation of this molecular Rorschach. At first, he gives a typical scientist’s answer.

“To me, it just looks like protease,” he says. Then he sighs reflectively. “I guess I’ve heard people say it looks like a Pac-Man … although nobody knows what a Pac-Man is anymore.”

When scientists at Merck & Co., the $ 17 billion New Jersey-based multinational, first made this molecular portrait, people still knew what a Pac-Man was. That was back in late 1988, which was also the last time Emini saw Irving Sigal, the brilliant young molecular biologist who convinced him, and Merck, that the protease would be HIV’s glass jaw. Sigal was the soul of Merck’s protease program; if not for him, Emini’s otherwise spare office would probably not be adorned with a sleek black promotional clock for Crixivan, the top-selling protease inhibitor, which Merck now can’t make quickly enough to keep up with demand.

A wiry, vigorous 35-year-old who crammed his leisure time with scuba diving, long-distance running and playing the sax, Sigal had been whipping his team to finish “solving” the protease when he had to fly to London to give a talk. Sigal hated to travel without his wife, Cathy, a Merck engineer whom he sometimes called three times a day. After the lecture, Sigal was supposed to stay over one more night. Instead, he called Cathy that evening from the airport and said he had been able to snag a seat on the red-eye.

Until recently, that flight, rather than the protease, was Irving Sigal’s legacy. It was Pan Am Flight 103, which was destroyed by a terrorist bomb over Lockerbie, Scotland. When the structure of the HIV protease was published in the British journal Nature two months later—and the coordinates deposited in a data bank so all scientists could use them—the news of Sigal’s death was included as an unusual humanizing footnote on the title page.

It was just the beginning of the drama in a decade-long, multibillion-dollar race pitting the world’s top drug companies against AIDS and one another—arguably the most time, money and scientific manpower ever focused on a single medicinal target. Emini recalls it as a “footrace,” and former FDA commissioner David Kessler as a “horse race,” but because of the way drug development combines human effort with technology and science, it was actually closer to an auto race. The Protease 500.

Before the finish line was reached, almost every aspect of the legal drug culture was turned upside down—or, in some cases, rightside up. The pharmaceutical industry revolutionized the way it discovered, developed and tested medicines. The Food and Drug Administration rewrote the rules of drug regulation. And AIDS activists evolved from medicine’s loudest outside agitators to its smartest inside advocates.

The result of their efforts is the new drug regimen known as “the cocktail.” It is a potent combination of three or four antiviral medications, including older AIDS drugs like AZT. But the cocktail gets its real kick from the protease inhibitors, three of which became the fastest-approved drugs in FDA history last year, with a fourth just approved and three more still in the pipeline. In many patients, the cocktail forces down the “viral load” in their blood (the new way HIV infection is measured) until it is undetectable. If this drug effect can be sustained—which is still uncertain, despite the flood of optimism in the media—it could change the disease from a death warrant to a manageable chronic illness in the 22 million people who have AIDS worldwide.

Some patients have already experienced such an astonishing reversal of symptoms that they have begun to ask the complicated questions of newly leased life, such as “How do I pay for $ 20,000 a year in drugs if I go off disability?” and “Do I like my caregiver enough to stay with him if I’m not going to die?”

The protease cocktail could turn out to be the biggest step forward in the treatment of any terminal illness in our lifetime. It has already forced one of the quickest treatment changeovers in modern medical history: In the first year protease inhibitors were sold, more than half of the Americans taking drugs for HIV infection added one, according to IMS, the company that does the “Nielsen ratings” of drugs.

Among those taking the new drugs are basketball legend Earvin “Magic” Johnson, Olympic diving champion Greg Louganis, author and former New Republic editor Andrew Sullivan and White House Interior Department liaison Bob Hattoy, who agreed to lend their personal experiences with the drugs to this retelling of the protease story. But they are not really the celebrities of protease inhibition; they are the grateful beneficiaries of the work of a group of researchers who toil in the medicinal trenches.

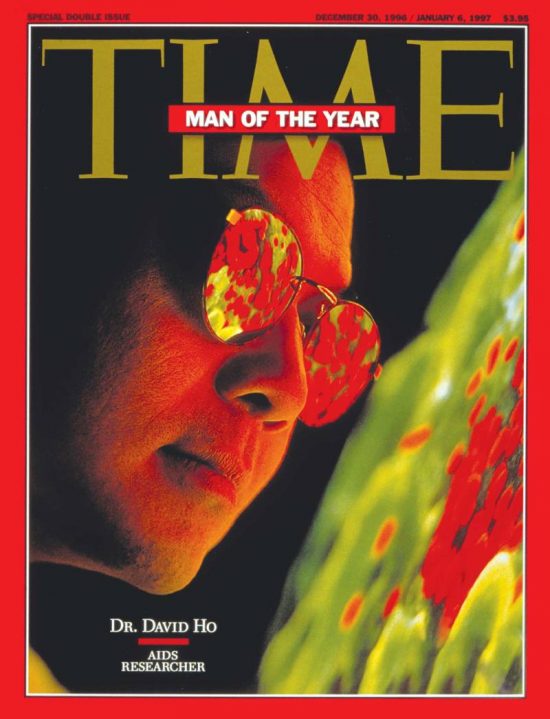

Perhaps the most watched of them is David Ho, the 44-year-old virologist who heads the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York, considered by some the “Manhattan Project” of HIV. Ho had become something of a scientific spokesmodel for the next wave of AIDS treatment even before being named Time’s 1996 “Man of the Year,” and he personally directs Magic Johnson’s care—recently announcing that a protease cocktail had rendered Johnson’s viral load undetectable.

But David Ho didn’t invent protease inhibitors. He is just one of a group of major international researchers, dubbed the “new guard” by the science press, who played a role in exploring their possibilities. And he is the first to acknowledge that the drug companies themselves—usually the least likely source of groundbreaking science—did most of the heavy lifting.

“The feeling in the labs,” recalls Merck CFO Judy Lewent, “was that this was Nobel laureate caliber work. And, in the drug industry, we don’t get to think about that all too often.”

The Race to the Cocktail began on March 28, 1986. That was the day that a team from Roche Laboratories, the unobtrusive New Jersey-based research arm of the $ 13 billion Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche Holding Ltd., published an article in Science that drew the first big theoretical bull’s-eye on the HIV protease molecule.

At the time, inhibiting protease was not the most promising new direction for AIDS therapy. AZT was being rushed toward FDA approval. Like the illness it was prescribed for, AZT would become a political as well as a medical phenomenon. It was the focus of the nascent AIDS activist community’s blistering critique of the FDA (too slow) and the drug industry (too greedy). AZT was the drug that ACT-UP, the seminal AIDS activist organization, was created to scream about. And because of the drug’s commercial success, its method of attacking HIV got the most drug company attention.

But Merck’s Irving Sigal saw protease inhibition as his chance to test a radical new theory about how drugs could be discovered. Medicines had traditionally been found by taking thousands of compounds found in nature—mostly soil samples brought back from around the world and placed in a “library”—as well as every compound the company had ever synthesized in its own lab, and screening them all to see if any had pharmaceutical potential. That’s how Sigal’s father, Max, had done things as director of research at Eli Lilly. But the next wave in drug development involved picking precise medicinal targets and designing molecules from scratch on the computer to hit them. This was referred to as “rational” drug design, as if the old way were somehow not rational.

The HIV protease was the ideal candidate for Sigal’s maiden rational drug design, because many companies already had experience shooting at a nearly identical drug target. Merck, Roche and several other firms were blowing millions trying in vain to develop a drug that lowered blood pressure by inhibiting renin, an enzyme remarkably similar to the HIV protease. Without those renin programs, Merck and its competitors might never have bothered to start HIV protease programs from scratch.

Merck chose to do both a full screening and a complete rational drug design. The company took its time, believing it was better to be best than first. Roche wanted to be first. At its Welwyn, England, research lab, it ran a tightly focused, entirely rational research program.

Full-blown AIDS was the end of the war, not the beginning.

The two companies toiled away for more than a year before Abbott Laboratories—the pugnacious $ 10 billion Chicago-based firm that, AIDS activists like to joke, “gets a D in ‘works well with others’ ”—joined the protease race in 1988. The head of Abbott’s antiviral venture, tough-talking former NIH virologist John Leonard, was hesitant to devote much time or money to protease inhibitors. Abbott was starting late, and its last AIDS drug had been blown out of the water in a patent dispute. So Leonard suggested that his medicinal chemists Dale Kempf and Dan Norbeck do their best with a modest expenditure. Abbott devoted a grand total of four people to the protease project, compared with 40 at Roche and maybe 400 at Merck. It quickly cast itself as a David against pharmaceutical Goliaths.

The protease race began heating up later that year when Merck published the first conclusive proof that inhibiting protease really did kill HIV. The company was about to be the first to publish the all-important “solved” crystal structure of the protease when Sigal’s plane was blown up, followed by the unrelated departure of several key Merck researchers to start the biotech firm Vertex. Those blows cost Merck’s program at least a year.

In the meantime, Roche became the first to formally test its protease inhibitor—known internally as RO318959, later to be called Invirase—in animals, in late 1989. Invirase passed, and the next spring the company also became the first to test its protease inhibitor in humans.

Merck, still struggling to recover from its setbacks, was just finally getting its first protease inhibitor into animals. But it didn’t take long for the drug to crash. “This thing is not going to work,” the toxicologist said when he brought Emini the news about the eight dying dogs. The rats weren’t doing any better. Merck’s drug had a nasty habit of shutting off bile flow to the liver. Emini felt that if the animal test results were that severe, it was “unethical to even do the study on humans.”

“So there went four years,” he says with a shrug.

Like a kid at a science fair for grown-ups, Dale Kempf was standing next to his poster waiting for someone to ask him about his protease experiment. At most scientific conferences, research that isn’t far enough along to merit a whole lecture is presented at lunchtime “poster sessions,” where several dozen scientists pin up a bulletin board’s worth of data and chat about it with whoever wanders by between sandwiches. On this day in April 1991, at a conference in Florida, David Ho wandered by and looked at Kempf’s poster, which included preliminary data on Abbott’s first try at inhibiting protease.

While Kempf didn’t know Ho, he certainly knew of him. Ho wasn’t yet as famous as Robert Gallo or Anthony Fauci, the U.S. government’s best-known AIDS sleuths, but he had published papers in the New England Journal of Medicine about how to quantify the amount of HIV in the blood, and had assays—biological testing materials—that might come in handy in Kempf’s research. They chatted for a minute, and then Ho moved on to the next poster.

But after the meeting, the two found themselves stuck in the same ridiculously long line at the American Airlines counter. They got to talking about their mutual interests, this time more animatedly, and by the time they finally headed to their respective gates, they had agreed to swap some of Abbott’s drug for Ho’s assay.

What began as a nice, collegial exchange between two working scientists turned out to be much more than that. Abbott Laboratories had hitched its protease wagon to a star. And the star had arranged for a supply of the fuel he needed to shine as brightly as anyone in AIDS research ever has.

David Ho is a casually serious, baby-faced virologist with wire-rim glasses, a dust mop of black hair and, invariably, a preppy sweater, shirt and khaki pants under his lab coat. Born in Taiwan, he was brought to the United States at the age of 12, speaking not a word of English, when his mother came to join his father, an electrical engineer, in Los Angeles. After years of bouncing back and forth between Boston and Los Angeles—med school at Harvard, residency at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center at UCLA, then a fellowship at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard—he had returned to California with his wife and three children in 1986 to do AIDS research at UCLA.

Ho was especially interested in what happened to the body in the early stages of HIV infection, a period that was still being described as dormancy because there were no visible symptoms. He thought that dormancy was counterintuitive, wishful thinking. So, beginning with a 1984 Science paper that described just how much of the AIDS virus could be found in the blood and semen of a “healthy homosexual man”—the answer, surprising at the time, was “a lot”—Ho had developed a reputation for interesting findings that were, in his words, “not exactly welcome news.”

In 1989, Ho was as surprised as anyone when he was plucked for what turned out to be one of the plum gigs in all of medical research. He was named founding director of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center for the City of New York. The Diamond Center (“No, we do AIDS research,” its receptionists are forever explaining to callers) is a shiny little basic science lab—from its DNA-emblazoned rug by the elevators to its high-design wood and stainless steel door treatments—on two floors of an otherwise dilapidated public health building at First Avenue and 26th Street. It is the scientific ward of a remarkably frisky lady named Irene Diamond, a woman on whom great wealth has not been wasted. At age 86, she is the largest private donor to AIDS research in the world. And David Ho gets to—in the lingo of lab culture—“burn” her money, earning him the enmity of many peers (including Robert Gallo, who derisively refers to Ho, in the book The Gravest Show on Earth, as “Dr. Diamond Head … not much of a scientist, but he knows how to play the political game”).

“It was very apparent to us that David was the right person.”

Irene Diamond had been in the movie business—she purchased and developed the script for Casablanca—and her husband, Aaron, made his millions in New York real estate. Longtime supporters of the New York arts, they decorated their apartment with a series of Picasso paintings and a unique upright piano with the curved lid of a baby grand that Lenny Bernstein said they must have. In 1984, they were walking on the beach in Key Biscayne discussing how to spend their twilight years giving away a lot of money to very “New York” causes in medicine and education.

A week later, Aaron Diamond died of a heart attack. Irene decided to follow through with their plan, donating $ 150 million to their foundation in 1986 and vowing to give away every penny in 10 years (including the interest, which brought the sum to more than $ 220 million). When the city hit her up to join a coalition to create an AIDS research center, Diamond decided to just pay for the whole thing herself.

Although the Diamond Center had a prestigious board and search committee, and was in partnership with the city and New York University, it was Irene Diamond alone who chose Ho, then all of 37, over many better-known candidates. “I took quite a lot of flak about David,” she recalls. “People thought he was too young, and couldn’t understand why I didn’t go after Gallo or [Harvard’s William] Haseltine. I said, ‘I don’t want a diva, and I want somebody young.’ I had also done a lot of reading about AIDS, and David felt that we should be throwing things at HIV in its early stages—which there wasn’t a great deal of agreement about … Eventually, everyone came around to him.”

Ho set out to quickly establish the Diamond Center as a lab that would attract top international talent to do solid, painstaking research, but would also use its freedom of curiosity to weigh in swiftly on AIDS questions of the day. Being under one roof—unlike the country’s largest AIDS research program, which was scattered throughout several departments at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB)—gave the place a Manhattan Project feel. Ho and his researchers were also at the epicenter of one of the most informed, activist AIDS communities in the country.

After Magic Johnson announced in November 1991 that he had tested positive for HIV, Ho stepped into the star’s spotlight. Los Angeles Lakers team doctor Michael Mellman turned to him for the major decisions about Johnson’s care.

“It was very apparent to us that David was the right person,” says Johnson’s agent, Lon Rosen.

“Although we did have to check his driver’s license, because he looks about 14 years old.” Johnson was immediately put on AZT and was told by Ho—overcautiously, it turned out—that he should not play professional basketball. Johnson saw himself as Ho’s ongoing “test experiment” of what the ideal treatment would be for an asymptomatic HIV-positive person in otherwise perfect health. Although he and Johnson met only occasionally, Ho stayed in close touch with his patient through his Fed-Exed blood samples.

Andrew Sullivan found out he was HIV-positive at the most depressing moment in AIDS treatment history, the summer of 1993. As he began the arduous information-gathering process that often comes with chronic illness, all he heard was more detailed bad news. At the International Conference on AIDS in Berlin, researchers discussed the controversial results of the largest trial ever done on AZT, the drug considered the “gold standard” for AIDS treatment. The study showed that AZT alone—which, for years, had been used by every AIDS patient taking antivirals and was still used by the majority of them—didn’t increase life expectancy even one day. In fact, slightly more of the placebo group lived longer.

As far as new drugs went, the protease inhibitor research delivered at Berlin was mostly about how the Merck and Abbott drugs hadn’t worked. Recalling his company’s humbling exposure there, Abbott’s John Leonard says, “I felt so sorry for the guy having to present that embarrassing story.” But he was also feeling a little sorry for himself. He was about to kill yet another protease compound and, “at that point, we’re in for about 75 million bucks.”

Just after the conference, the AIDS community watched the sad meltdown of Yung-Kang Chow, who had to retract the once-promising HIV drug study that had caused the tabloids to dub him “Dr. Hope.” Hounded from AIDS research because of methodological mistakes, Chow would never get any credit for his treatment innovation: His flawed experiments were the first to popularize the concept of using three antiviral drugs together instead of two, the first three-drug cocktail. At the time, his fall was just more bad news.

“The massive media hype about hopelessness was just horrible,” recalls Sullivan. “There were waves of stories saying ‘no hope for AIDS drugs.’” While it wasn’t easy, Sullivan was able to track down some obscure studies that were promising. “I basically decided that while nothing was a cure, the rate of research was such that if you could hang on, you’d get on one slowly sinking ship and by time it was under the water another would be there. I was just convinced I caught it very early and had a long time to live.”

Merck already knew it would not win the protease race, but it didn’t care. Emilio Emini had so little respect for the Roche drug that, as far as he was concerned, it was “still just us and the virus.” Everybody knew the Roche drug had low “bioavailability,” meaning that although the drug did its job well on HIV cells in a laboratory, it couldn’t be kept “available” in the bloodstream long enough to perform the same tasks in the body. The liver quickly skimmed the drug out of the blood.

When Roche had committed to its compound in 1989, it believed that bioavailability would always be a problem for any protease inhibitor. But, with an extra three years of medicinal science, Merck had been able to dramatically improve bioavailability. In fact, Emini finally had an inhibitor he liked. L-735,524, eventually to be called Crixivan, was getting excellent results in animal tests and human tests. In December 1993, at the First National Conference on Human Retroviruses and Related Infections in Washington, Merck made its initial presentation on the drug, giddily announcing that three patients in the Crixivan trial had seen the virus in their bodies driven down to undetectable levels. The only problem was, as the test results were being announced, the virus in two of the patients was already mutating around the drug, building up resistance. Merck just didn’t know it yet.

Late one freezing January afternoon, it found out. Molecular biologist Jon Condra, one of the few Merck employees who had been brave or stupid enough to make it in to work through the drifting snow, was scanning computer analyses of the viral RNA from the subjects in its protease trial. There are 99 amino acid positions on each strand of RNA, and a mutation can start at any one of them. The computer notices any change and announces the bad news by replacing a hyphen with a code.

Condra’s tired eyes caught the blue “V82T” on the screen. “Oh, no, it finally happened,” he said to himself. The mutation was at position 82, which was right where Merck’s “rock” fit into the protease’s “mouth.” Condra called Emilio Emini at home and told him to log on to the company’s computer system right away. Emini was horrified.

The mutation was just part of the bad news. That same day, Emini learned that a revolutionary new test had detected HIV in Merck’s so-called “undetectable” patients. Until that time, HIV-infected blood had been tested for p24, a viral protein believed to be the best available “surrogate marker” for the actual viral level. With the new test, it was possible to measure the actual viral RNA itself, or what would come to be referred to as viral load. In most of the patients, viral load was rebounding.

The Merck protease inhibitor looked doomed. The only hope was one guy in Protocol 010, a study at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, who was still “undetectable” even after the new viral load tests. He was a law student in his early forties known to the researchers only as Patient No. 142. Since Emini couldn’t drag him up from downtown Philadelphia to be interrogated and probed, he peppered No. 142’s physician with questions about him. And whenever No. 142’s blood was retested, everyone checked the computer for the results. “We just kept looking at this guy,” recalls Emini. “He was the only patient keeping the hope alive. This is the guy who kept us from just throwing our hands in the air.”

Patient No. 142 was on the higher of the two doses they were trying. So, instead of just dropping the drug, Merck took the risk of starting a new trial with everyone at much higher doses.

The researchers also began another trial combining their drug with AZT and other antivirals: a protease cocktail. Although combination therapies historically were more common in virology than in other areas of drug treatment—and about 19 percent of AIDS patients were already using AZT and the new Roche antiviral ddC together—this was still a radical move. Protease inhibitors had been developed to blow all the other AIDS drugs out of the water. Drug companies don’t normally spend hundreds of millions of dollars to develop really expensive drugs that only work when taken with the really expensive products of their main competitors.

But the AIDS virus was forcing drug companies to do lots of things they wouldn’t normally do. And with mounting pressure from the finance side to kill the protease inhibitor, Merck researchers wanted to give Crixivan one last chance.

Abbott had been quietly testing a new compound of its own in Europe. In early 1994, the company decided to bring some of the compound, ABT-538, which would become Norvir, back to the United States and give it to David Ho to test. He and his colleague Martin Markowitz gave the drug to 20 patients. They were very interested in what the results were telling them about the power of the medication. But what really fascinated Ho was what the drug and these new viral load tests were telling him about AIDS.

“Week after week we’d see the virus go down so dramatically,” he recalls. “We realized it should go down, but not by that magnitude. Why does the virus go down so much? I’m just sitting, staring at the data. And it’s telling me that once you block the production of virus, the virus that is already present is being removed very quickly. When you start to think through the numbers, you can just sit down with the back of an envelope and calculate what it means using simple math. It says the virus is replicating at a tremendous clip and the body is removing it at a tremendous clip.”

With this information, Ho realized he might finally be able to prove his long-held, sparsely shared view of what AIDS really was. It wasn’t a viral time bomb. From the minute it got into the blood, it was a goddam Roman candle.

“It explodes in the first weeks,” he says excitedly, “to enormous levels, millions and millions of particles. But this is brought under control spontaneously when the person starts their immune reaction to HIV. The body checks the explosion fairly well, and what occurs after that is what we call ‘dynamic equilibrium’ between the person and the virus. It could look like the patient is holding his own. But what is really occurring is that the virus is just cranking, just churning out tens of billions of particles a day, every day. The patient feels nothing, because the initial battle line is drawn and it’s stable for a long time, with high casualties on each side.” Full-blown AIDS was the end of the war, not the beginning.

Ho was so excited, he would wake up in the middle of the night with ideas about how he could prove his points better. Showing how rapidly the AIDS virus replicated and died in the body—about half of it turned over every two days—was going to be the observation of a career. Even though he knew he should keep quiet, Ho could hardly contain himself around colleagues. Several weeks after the breakthrough, he found himself in Seattle for a conference, and went out to dinner with a bunch of the world’s top AIDS researchers, including oncologist George Shaw—who, with his wife, molecular biologist Beatrice Hahn, runs the AIDS program at UAB—and virologist Dani Bolognesi from Duke University.

“Dani sat there and we were just talking about science,” Ho recalls. “And he asked a question: ‘I wonder how fast the virus is turning over.’ George and I simultaneously gave the answer. And it was the same answer.

“And then we just looked at each other.”

Shaw knew. The moment couldn’t have been more pregnant. After all, AIDS research had been forever discolored by an epic clash over who deserved credit for the discovery of HIV. Nobody knew that better than Shaw, who had been doing postdoctoral research with Robert Gallo in 1985 when the virus hit the fan.

And now Shaw and Ho could see medical history trying to repeat itself. Shaw’s group had made pretty much the same observations as Ho’s, at the same time in a similar number of patients. The only difference was that Shaw had tried not only the Abbott drug but the Merck drug and even nevirapine, a potent experimental antiviral from Connecticut-based Boehringer Ingelheim that worked more like AZT (and would later be marketed as Viramune). Both men knew full well how to race to publication. The new custom among young science-media-savvy researchers was to play the major journals, Science and Nature, off each other in order to publish even a week ahead of the competition. Then they could spend the next year fighting over bragging rights and trolling for Nobels.

Instead, Shaw and Ho spared the AIDS world and agreed to submit separate papers, simultaneously, to Nature.

But with publication some months away, they began looking for a more immediate opportunity to share some of the exciting data with their colleagues. There was only one problem. The drug companies owned the data. And Abbott, especially, was reluctant to let them release it. Regardless of how excited Ho and Shaw might be, neither Abbott nor Merck had committed to actually marketing their protease inhibitors. The “go/no-go” decisions, which could mean immediately doubling the hundreds of millions the companies had already sunk into Norvir and Crixivan, were waiting to be made.

When the flier came up on the fax machine, Spencer Cox couldn’t believe it. His fellow AIDS activists were calling him a Nazi and comparing him to Jack Kevorkian—all because his group was trying to hold up the Roche protease inhibitor studies.

Cox was a member of TAG, the Treatment Action Group, which had splintered from ACT-UP and helped define a new subculture of treatment activists who operate at a level of technical knowledge that even the scientists find amazing. Because of their efforts, for the first time in pharmaceutical history the development of a drug would be heavily influenced by the people who actually took it. The government reorganized its entire AIDS research program based on a TAG critique, and the group, along with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and Project Inform, had played a major role in getting the FDA to set up an “accelerated approval” program that created a separate “fast track” for AIDS drugs. They also had influence with potential test subjects: Discouraging words from activists could hinder enrollment in clinical trials.

But now TAG had exposed the raw nerve at the root of every drug development process: the unwinnable debate between more access and more testing. Some treatment activists believed that “accelerated approval” should be used to get promising compounds out the moment they looked promising. Others believed that accelerated approval was too fast, and they didn’t trust the drug companies to do the necessary follow-up studies once their drugs could be sold under this new, conditional approval. TAG was in the “slow-down” group, and its most visible members, including Cox, were among the loudest voices on the new National Task Force on AIDS Drug Development—the forum that was turning the normally secret competition among drug companies into a noisy public spectacle.

TAG was trying to use the Roche protease inhibitor to test the brakes on accelerated approval, fearing that the company would throw the drug onto the market “without caring if it harmed patients,” says Cox. But TAG was immediately attacked by a combination of West Coast activists and angry New Yorkers. And in the fall of 1994, it was forced to retreat as excitement about the protease inhibitors increased.

“They’re crazy,” the FDA’s Jeff Murray said when he got his first look at the astonishingly aggressive new development plan Abbott had filed for Norvir. “There’s no way this can be done.”

When the people at Merck heard that Abbott planned to cram what would normally be several years of clinical testing into less than a year—basically squashing all three phases of FDA approval into one—they agreed it was crazy. Except they knew it could be done. And if they weren’t willing to do it, too, Abbott was going to leave Merck in its dust. Emilio Emini was always quick to take a swipe at the Abbott drug: “It is intolerable to take,” he says. “You can go out and ask.” But he knew his Crixivan was about to go from a very smug second to a painfully distant third, unless the company did something entirely un-Mercklike and rushed into wide-scale testing.

Abbott had signaled, through David Ho, its intention to put the pedal to the metal with Norvir. After meeting with Ho and Michael Saag—who was George Shaw’s clinical trial expert at UAB—in Orlando the night before a big immunology conference, Abbott top brass had finally agreed to release the study data and green-light the drug. At that moment, the protease race shifted into an overdrive higher than anyone in the drug business had ever experienced.

As the Shaw and Ho papers were appearing back-to-back in the January 12, 1995, issue of Nature, Merck CEO Raymond Gilmartin countered Abbott by approving the first huge clinical trial for Crixivan: 4,800 patients in 11 countries. By the end of the month, at the Washington Retrovirus Conference, it was clear to anyone paying attention to the field that the protease inhibitors could become the first AIDS drugs that actually worked.

Unfortunately, hardly anyone could get them. One group of underground activists began gathering technical information and money to manufacture some Crixivan on their own. The AIDS Project Los Angeles newsletter was soon reporting what the underground price might be: $ 10,000 a year.

At the end of February, the AIDS Drug Development Task Force held its long-awaited meeting on protease inhibitors. David Kessler had to personally twist Abbott’s corporate arm to get the company to show up and share what, for any other drug being reviewed by the FDA, would be considered absolutely secret, proprietary information. The activists, the researchers and the competition got an opportunity to publicly grill the firms about the most minute aspects of their research plans. Much of the pressure concerned “compassionate use” programs that would get the drug to people who otherwise wouldn’t live to see it approved. Roche had a program, but Abbott and Merck did not, insisting it was costing them millions just to make enough of their compounds to conduct their clinical trials.

Merck still wasn’t sure it was going to market Crixivan at all—even though the higher dose worked much better. The company finally decided to take a huge gamble and, in March, invested millions in retrofitting plants in Georgia and Virginia to manufacture Crixivan if the company decided to apply for FDA approval. But it was still a big “if.”

By early summer, the activists were frantically trying to get drugs for compassionate use. They were also keeping friends abreast of every opening in every clinical trial—each one of which had its own rules about how sick the patients needed to be, and what other drugs they could be taking. Andrew Sullivan was unable to get into a trial: He was told he wasn’t sick enough. For the time being, David Ho decided he didn’t want to take the risk of using experimental drugs on Magic Johnson, who was already doing well enough on a combination of antivirals.

Greg Louganis’s doctor got him into the trial for the Abbott protease inhibitor. By this time, the retired Olympic diver had been taking medication for his HIV infection for more than seven years, and his coming-out autobiography had been on the bestseller lists for several months.

He started taking the experimental Abbott protease inhibitor during his book tour. The side effects were immediate and, literally, gut-wrenching. “A half-hour after I took it,” he recalls, “I was either flat on my back with no energy, or on the toilet.” Even though he got constant encouragement from friends like activists Larry Kramer and Mary Fisher—whom he would talk to while on the road—he wasn’t sure he could continue taking the drug, especially after the side effects forced him to postpone a book signing in Denver.

But even though he felt like hell, the drug was working wonders on his viral load levels, so he felt trapped. “It messes with your self-esteem,” he says. “I felt I should be able to be stronger. I always said I didn’t want HIV management to be my second occupation. And here my quality of life was being consumed by my HIV drug.”

In July 1995, David Ho had an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine that declared a new standard of care for HIV infection. His team had been combing New York hospitals to find patients who knew, for whatever reason, that they had just been infected. Based on his observations of a dozen such patients, as well as many other studies (including the groundbreaking viral load work of John Mellors at the University of Pittsburgh), Ho declared that it was “time to hit HIV early and hit it hard.” If Ho’s proclamation was correct, AIDS might be turned into a manageable illness. Either way, he had just dramatically increased the size of the $ 1 billion antiviral AIDS drug market (which, by drug company standards, still wasn’t very profitable) because patients would now take the drugs from the moment they tested positive, instead of waiting months or years for full-blown AIDS.

Merck held a lottery to choose 1,100 AIDS patients for compassionate-use supplies of Crixivan. More than 11,000 people signed up for the spots. Several weeks later, Roche applied for FDA approval to market its drug Invirase. David Kessler decided to send a signal to Merck and Abbott that he wanted to see their protease applications on his desk, too. He chose a “Nightline” appearance with Larry Kramer as the forum. Kessler went on the show “and basically came as close to saying these drugs are safe and effective as I could,” he recalls. “I almost sent them the approval letter [over the air]. I figured that was the best incentive. I wanted them to know we were ready, and there should be nothing holding them back.”

“David has been really shocked by the hostility that success has brought him,” says Ho’s colleague John Moore.

At the same time, Abbott was meeting quietly with Roche to discuss an odd pharmacologic plot twist. Abbott had accidentally discovered that its drug made the Roche drug more bioavailable—Norvir actually blocked the body from dumping Invirase out through the liver. Roche, distrustful of a competitor claiming to have “raised Invirase from the dead”—when it didn’t think the drug was dead—had initially blown off Abbott’s inquiries about the interaction, which might allow the companies to team up against Merck. To pressure Roche, Abbott filed for a patent on the idea of using the drugs together, and then submitted a “late-breaker” paper to the next big scientific meeting to publicly announce the promising interaction. Finally, Roche agreed to negotiate a deal to study the drugs together.

In the last lap of the race, it would be the collaborations between competitors that would make the difference in creating the most potent cocktails. One of the breakthrough trials for Merck studied Crixivan with the Glaxo-Wellcome antivirals AZT and 3TC. It was just one of the many examples of some of the most “elegant” science the drug industry had ever seen.

Unfortunately, the protease race was about to hit the wall of money—the inelegant moment when science officially becomes commerce, and exciting new drugs are finally handed over from the lab nerds to the marketing types. On December 6, 1995, the FDA approved Roche’s protease inhibitor. Almost immediately, Roche’s director of virology, Miklos “Mickey” Salgo, found himself jousting publicly with Emilio Emini over which drug patients should take. Salgo was incensed at Emini’s suggestion that dying people wait to start protease inhibitors until Merck’s was available—especially when he said it during a “state of the art” talk at the Washington Retrovirus Conference, a high-minded forum never previously sullied by marketing maneuvers.

The Abbott drug was approved on March 1; the Merck drug on March 14. Without identifying which protease inhibitor he chose for Magic Johnson, David Ho acknowledges that he did wait for the later approvals before starting him on one.

Andrew Sullivan chose the four-drug cocktail with the Abbott and Roche inhibitors, because they appeared fractionally stronger than the Merck drug alone. He suffered severe side effects, some of which influenced his ability to continue as editor of the New Republic. Before he resigned and “came out” with his HIV status last spring, Sullivan had nightmares of walking down the street haunted by “this huge noise of rattling pills … In every seam of my clothing there were pills.” Today, being a human shaker for the cocktailrequires Sullivan to swallow 23 pills a day (including the two protease inhibitors and Ritalin to combat drug-related sedation) at three separate feedings. But his excellent viral load numbers, which he obsessively charts on his computer, have been worth it.

Greg Louganis refused to put up with the side effects, and quit the Abbott clinical trial. Ironically, when the Abbott drug was approved, he was asked to give a pep talk to the company’s sales reps. Instead, he lectured them about what it was really like to take their drug and urged them to keep in mind, during their “struggle for the almighty dollar … [that] not every drug is for every person.” He joined another cocktailtrial with nevirapine instead of a protease inhibitor. But, after several months, he discovered—by having his pills analyzed—that he was in the group taking the placebo. Angry and dejected, he briefly eschewed all medications, and only started treating his HIV infection again after a dramatic scene at a promotional appearance for the paperback of Breaking the Surface.

“This kid, who was diagnosed the same time I was, asked me how I stayed motivated to take my meds,” he recalls. “I just started crying. I said, ‘I don’t deal with it well, especially not right now.’ ” Shortly thereafter, he stopped drinking, stopped smoking and went on a Crixivan/nevirapine cocktail.

The Protease 500 was over. And the victory lap was soon spoiled by price, supply and all the other mundane realities of scientific commerce. Last July’s 11th International Conference on AIDS in Vancouver became the coming-out party for the data that had been presented, or predicted, in Washington. But just as Science magazine announced how great all the “new guard” scientists got along, David Ho and the Diamond Center dumped host New York University and made a new alliance with Rockefeller University. Behind the scenes, people were clicking their tongues about scientists “overpromising” what the protease inhibitors could actually do, and complaining about who got the most individual press for this highly collaborative effort. Even before being named Time’s “Man of the Year,” Ho was feeling the heat.

“David has been really shocked by the hostility that success has brought him,” says Ho’s colleague John Moore, who on the side “serves as David’s minister of war … The older generation in AIDS research are threatened by the new group coming up … Their place in the sun is going or gone in some cases, and they hanker for their youth. Tough luck.”

And, regardless of all the histrionic “AIDS cure” stories, nobody knows what “undetectable” viral load in the blood really means or how long it will last. The virus might still be lurking in lymph or brain tissue, but that’s not easy to assess—how much of their bodies can test patients be expected to donate to science while still alive? The drugs are being sold at prices ranging from $ 5,000 to $ 8,000 a year. There is now a fourth approved protease inhibitor, Viracept, from the biotech company Agouron, and Roche is testing a new soft gel formulation of Invirase with better bioavailability. But these are still, by the normal standards of drug development, experimental medications. Those taking them are part of an ongoing science project. Some activists have now turned on the drug companies again, complaining about high prices, short supplies, inadequate testing of various cocktail combos, and the withholding of protease inhibitors from patients whom doctors consider too unreliable to take them properly.

But it has become harder and harder to guard one’s optimism. NYU’s Roy “Trip” Gulick, a charismatic young clinical researcher, remains perplexed by the dilemma inherent in a recent conversation he had with an AIDS patient. “He came in,” Gulick recalls, “and said, ‘I’ve got to thank you. I feel like I have my life back again. I had been planning for my death and now I have to start planning for my life.’ How do I express my cautious optimism to him, and get him back to the facts?”

At the end of the day, Bob Hattoy sits in his office at the Department of the Interior, wondering if he can learn to love again. “I’m willing to enter into this relationship having been burned in the past,” he tells me. “It’s a very intimate thing, you know. And you’re very leery: ‘No, it won’t be like that this time. No, this time it will be supportive, it will make you better.’ ”

Hattoy, the highest-ranking member of the Clinton administration who is open about being gay and having AIDS, is not talking about a new man. He is talking about protease inhibitors. “It’s like you have to make love to the drug,” he says. “And, all you want to know is, is it safe?”

Among his friends, Hattoy was one of the last to try a protease inhibitor. When the AIDS task force he sits on persuaded President Clinton to grant $ 52 million to help patients pay for the new drugs last year, he was still deeply ambivalent about taking them himself. When Clinton asked whether Hattoy was taking protease inhibitors himself, he told him, “No, I’m not sick enough yet.” He knew that was only half-true.

Hattoy almost died of AIDS-related lymphoma during the 1992 presidential campaign. After successful chemotherapy, he avoided all medicines, including antivirals, for years. But last summer, he found himself feeling weaker. He went to the doctor, got his first-ever viral load test, and was prescribed AZT and 3TC. And, for the first time since he tested positive in 1989, he actually took the antiviral drugs on time, every day, believing they might actually do something.

He realized he had been “busy saving the world and not taking care of myself, which happens to activists. I became a little grandiose, a little egocentric, but being a visible person with AIDS, I’ve been bombarded with every treatment activist, every scientist, every peach pit and crystal therapy. When I first heard of protease inhibitors, I just thought, ‘Great, great. One more thing that eventually is not going to work.’ ”

He has, in the past year, watched people seemingly brought back to life by the drugs, and watched others die on the drugs. Viral load testing is new, but its results have a familiar ring. “It’s still a bunch of guys sitting around comparing who’s bigger,” he jokes. “We’ve just become viral load size queens.”

In January, Bob Hattoy took his first protease inhibitor. He’s expecting to receive his first post-protease viral load results any minute. “Many of us had already decided we’d live for a while and there wouldn’t be a cure,” he says. “We made some decisions and some changes based on that. To decide, ‘My God, the protease inhibitors might not be a betrayal and we might live for a long time’—well, that profoundly changes how you view yourself.”

He sighs. “It’s just so hard to intellectually embrace science again and psychologically embrace life. It’s a leap of faith.”

Note: A longer version of this piece appears in Fried’s 1998 book Bitter Pills: Inside the Hazardous World of Legal Drugs. All the people with AIDS profiled in this story are still alive and well because of protease inhibitors, except for Bob Hattoy, who lived another ten years but died in 2007 at the age of 57, and Spencer Cox who died in 2012 at the age of 44.

Postscript by the author:

So fascinating and reassuring to see Dr. David Ho on MSNBC last night. I hadn’t seen him for nearly 25 years, but it made me feel so much better he was on the case–just as it did in the 1990s when I was fortunate to spend a lot of time interviewing him, and all the other researchers whose work led to the creation of the protease inhibitor drugs for HIV.

I was, at the time, on assignment from Vanity Fair, where the art director had been one of the early AIDS patients treated successfully with these new medications. Graydon wanted me to write about them (I was the go-to pharma guy then) but the challenge was how to write a really VF-style narrative about drug development. David Ho and his team at the Aaron Diamond Center (whose founder, Irene Diamond, was still with us) were key to that narrative. But, after having done several years of investigative stories on drug safety with less-than-zero cooperation from drug companies, I was also amazed that Merck, Roche and Abbott let me have great access to their research scientists.

And four high-profile men who were openly HIV-positive but had never discussed their treatment—Magic Johnson, Andrew Sullivan, Greg Louganis and Bob Hattoy—all agreed to for this piece. It was a journalistic experience I will never forget. Nigel Parry took stunning pictures, and my editor Wayne Lawson was his usual brilliant, erudite self through the whole process.

But don’t go looking for it in that fancy new Vanity Fair archive. It isn’t there. Just before we were about to go to publication, Time Magazine made David Ho its Man of the Year. And even though the story with that cover was not very substantial, Graydon decided he had been scooped. He gave me back the story and let me sell it to the The Washington Post Magazine—which did an incredible job with it in May of 1997. I was lucky to be able to work with Liza Mundy and a great team of editors (who I first met through Bob Thompson). A version of the piece appears as the last two chapters of my book Bitter Pills.

My only regret is that my father didn’t live to see it published. The piece was the only thing I was working on in 1996 after he was diagnosed with cancer. It would have been in the February 1997 issue of VF and he could have seen it. But he got to read the manuscript and tell me he was proud of me. And he got to know about David Ho and the power of emergency science.

Fact-checking for the piece was the last time I talked to David Ho. But seeing him on TV last night brought me the first relief I’ve had since this whole thing began.—Stephen Fried (March 15, 2020).

[Photo Credit: Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash]