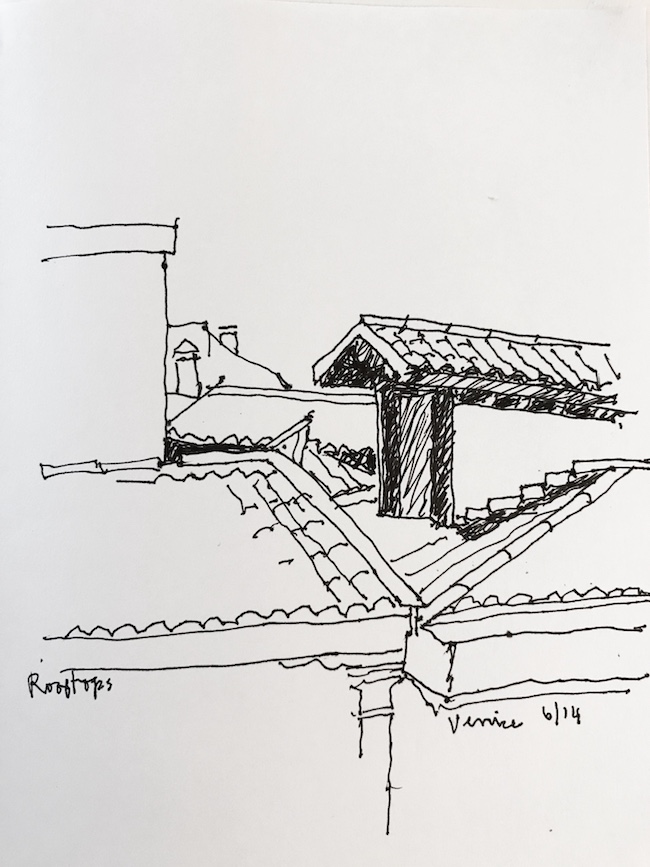

She stands in the small kitchen of the ancient building by the canal. The stove rides at a right angle to the wall so that she can look out while she cooks in her fourth-floor aerie. She cannot stand to cook if she must stare at a wall. That’s the reason the exhaust hood hovering over the four burners is translucent. She must see, always. She is a creature of her senses, particularly smell.

Outside, Venice slides quietly into early evening. The kitchen faces south to capture the light and looks at the Campanile, a 325-foot brick spike that towers over the piazza San Marco. The kitchen we are standing in has been wedged into a building thrown up in 1525. Like everything here, the place keeps settling, as the deep piles under the structure slowly wrestle with the quagmire of the Venetian lagoon. Every cake she bakes in her oven lists to one side.

I’m here to attend cooking school, my first and only visit to the Europe my ancestors fled, thank God. The woman in the kitchen smoking the Marlboro Light is my teacher. I stumbled on her a while back when someone cooked a lamb stew for me that made me snap awake. I looked at the recipe, which could have fit on a matchbook, tried it myself, and haven’t been the same since. Bought the book, marched through the simple, clear instructions, and slowly lost a grip on my heritage. I come from a people who feel food is something to murder and who were noted for a menacing use of frying pans. I did not visit a French restaurant until well into my twenties and frankly missed the ketchup.

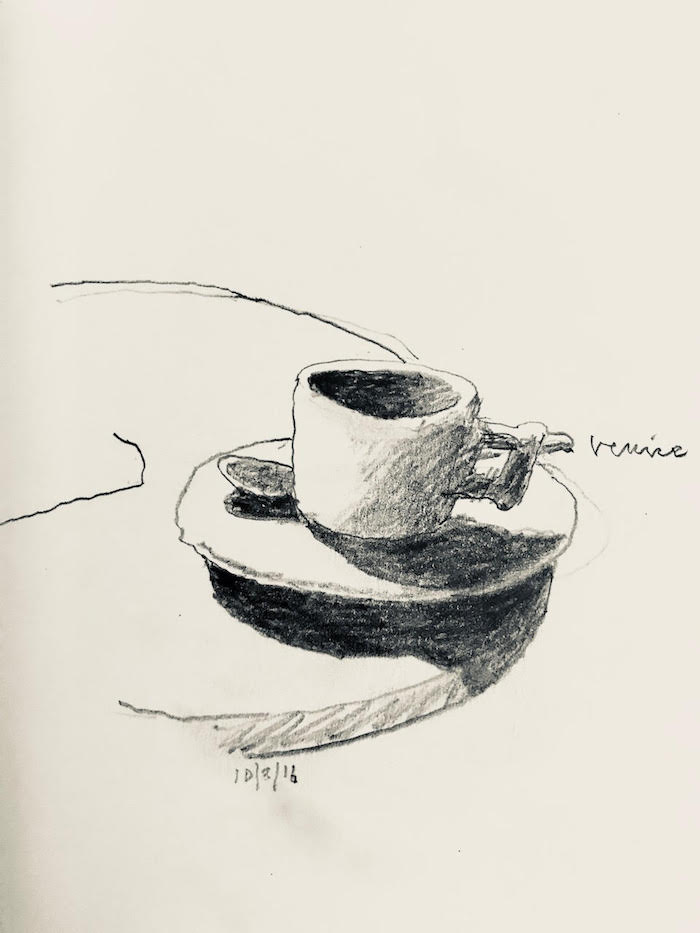

She is talking now, in that wonderful, husky voice. She wears a dark dress and two strands of pearls, and when she makes a point, her left hand, holding her cigarette, sweeps theatrically. She is an educated woman, a trained scientist, and, alas for me, she does not suffer fools gladly. The kitchen lights paint the dark windowpanes a milky color, and I can see her reflection and, beyond, the skyline of Venice, and she is talking philosophy, how she teaches….well, she teaches common sense. That’s it, she says, that is the most important ingredient in the kitchen. I think of hanging out at one of my uncle’s places, a beat-up trailer, when I was 7 or 8, and he is smoking a cigarette and leaning over a skillet of corned-beef hash black with pepper, and he takes a drag, pauses, and reaches over and has a good pull on his bottle of Jim Beam and goes back to the crackle of grease in the skillet, face hovering in the blue air as he cooks up our dinner, and I’ve got to wonder how I got from a life of slop, fast food, and midnights at Denny’s to this room.

This is one of the lessons: Get fresh things and eat them, because some things cannot be improved on.

She plucks a tomato from a basket, a small type called cigliegini she has just brought up from Sicily. This particular strain grows near the sea in salty soil and sucks in salty air, and as her husband points out, none of this is good for the plant.

She gestures with her cigarette and says, “Taste it, taste it.”

I pop the small red ball in my mouth and bite, and flavor explodes—Sicilian dirt, salty air, various invasions, Don Corleone, God knows what else. This is one of the best tomatoes I’ve tasted in my life, a quirky peer of vine-ripened specimens I plucked as a boy from my kinfolk’s farm gardens in Iowa.

She smiles. This is one of the lessons: Get fresh things and eat them, because some things cannot be improved on.

I savor the tomato and look at her. Her hands are liver spotted, her voice husky from cigarettes, her gaze quick and very alert, her tongue sharp. She speaks with authority, and yet her eyes flash a kind of girlishness. She is at ease with herself and amused by the world. Because she knows, and she can taste the knowing.

She says, “I do not teach recipes; I do not measure things.”

That’s the rub. She has taken something simple—the home-based cuisine of Italy—and made it even simpler. She is a culinary Spartan, a woman with a tiny refrigerator, a woman who stocks her itty-bitty freezer only with ice, meat broth, ice cream. And vodka.

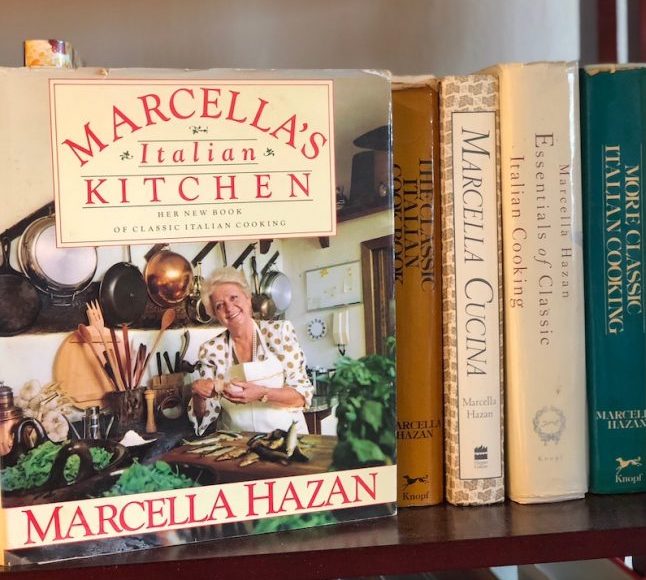

Her name is Marcella Hazan, and she is the most influential Italian cook in the world. Her fundamental cookbook, Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, has gone through more than fifteen printings and taught Americans that Italian food is not tomatoes and garlic, some Chianti, and good night. She introduced us to the idea that Italian food was good and serious and worth time and trouble. But the rest—the big restaurant bills, the ingredients obsession, the pilgrimages to expensive pots-and-pans stores—has very little to do with the woman smoking the Marlboro. In a world of competitive consumers, she is a dinosaur dedicated to simplicity. Here, here, taste the tomato.

She has a style much like the fabled Zen masters who periodically whack their charges with a board to help them down the path to enlightenment.

For twenty-nine years, she ran a cooking school in her kitchen, six students at a time. And then, six years ago, she thought the hell with it and decided to get out of Dodge—well, Venice—and retire with her husband Victor to Longboat Key, Florida. That’s why I broke down, cast virtue to the wind, and visited what I’m now told is Old Europe. I wanted to be there as Marcella Hazan cooked her last supper.

School runs six days and costs three grand, and my classmates are all graduates. The curriculum is pretty simple: meet precisely at ten in the morning, cook all day, with two breaks—one when Victor, an internationally recognized Italian-wine authority, lectures us on different varietals and marches us through tastings of his near-thousand-bottle cellar, and then one to eat a leisurely meal about four in the afternoon. There are usually but six students at a time, and for years the waiting list has been long. I am the only representative here from the world of Spam. My classmates are devoted amateur cooks, fiends for Italian food, and they are a little intimidated by Marcella, who is now running at Ferrari speed and teaching us a simple veal sauce.

She has a style much like the fabled Zen masters who periodically whack their charges with a board to help them down the path to enlightenment. The Hazans have a large and ancient sculpture of the Virgin Mary in their living room, and when someone asks about its history and meaning, Marcella stares blankly for a moment, says, “We saw it, we liked it, we bought it,” and then shrugs. But like the fabled Zen masters, she has a genius, and right now, at about eleven on the first day of school, it is focused on ground veal, fresh tomatoes, an onion, and some butter—the elements of her veal sauce. The recipe came into being because she wanted a quick and lazy substitute for the full-blown ragù of Bologna that takes hours and hours of simmering and reducing. She wanted to probe inside this ragù, and extract its essence.

Recipes are sketches, not laws, and when Marcella Hazan enters a kitchen, she follows her instincts and her nose.

First we peeled the tomatoes with a swivel-headed vegetable peeler, cleaned them of seeds, and chopped them up. Then we tossed some butter and vegetable oil in a pan, put in a whole small onion (with a knife-inflicted cross at the top so it would cook through), and applied heat. The whole recipe is in one of Marcella’s books, but we all note that she is instantly deviating from it. That’s the first lesson, unspoken but there: Recipes are sketches, not laws, and when Marcella Hazan enters a kitchen, she follows her instincts and her nose. She flings in paddles of butter from a waiting tub and adds salt by the fistful. She rarely tastes what she is cooking but makes most decisions on the basis of smell. I am in the presence of a snout that would be the envy of a world-champion truffle-hunting hog.

She knows. She knows exactly how to make a very simple veal sauce, for a very simple reason: She is going to eat the simple veal sauce, so it should taste the way she wants it to taste. We stand in a circle looking at the bubbling pan of veal, tomatoes, onion, salt, pepper, and butter as the morning light streams into the rooftop kitchen. We have traveled halfway around the world to witness the obvious, and I am here to tell you I have seen the obvious, and it works. Marcella Hazan has mastered cooking for people who like to eat. Once she was asked in an interview how much thought she gives to presentation, and she responded none, because the food on the plate will not look that way in twenty or thirty seconds. I wanted to cheer.

Her cookbooks read simply and clearly because they must suit her. She writes them in Italian; Victor casts them into English. She spends years on each book, fiddling with a recipe endlessly before she concludes it is ready for the world to taste. Only at the last moment, when she needs to put it in the books, does she measure what she has been doing.

Marcella Hazan seems to almost dread inventing a recipe, as if it were a bit of shallow flash. She points out that there are 60,000 codified recipes in Italy and adds, “That’s only the ones written down.” On a peninsula almost sinking from the weight of history, she is keenly aware that very little that grows or walks the earth has not been confronted by an Italian kitchen, and it is a lifetime job just to sample what is known. She cringes at the notion of fusion cuisine, some kind of novelty for novelty’s sake in her eyes. She is true to her faith, and her faith is in the simplicity of Italian food. Italian food is simple because it is the product of the historical kitchen of poverty.

We have traveled halfway around the world to witness the obvious, and I am here to tell you I have seen the obvious, and it works. Marcella Hazan has mastered cooking for people who like to eat.

I am snapped back to alertness by Marcella announcing, “Let’s see if you remember anything” to her gaggle of former students. The veal sauce is under way, and now we must tackle drunken roast pork, cauliflower, and for dessert, yogurt and Sambuca cake—the last, a concession to the customs of foreigners, since a proper Italian cook might make one cake a year at most.

But the test our leader is flinging at us is called menu—all these courses are supposed to complement one another, you know. I’m at sea here, because I’ve hardly cooked a meal during my days on earth with more than one course. But Marcella’s point is simple, and here is her answer: The mellow pasta dish sets it up, then comes the drunken pork in a wine sauce, and therefore the vegetable should not have a sauce. Why? “Because,” she decrees, “they’ll mix together.” I have never thought this way in my life, which means, I think, that I have never really given food thought. Then: The vegetable must be fried or baked and, most important, dry because the pork is sauced and strong. She eyes us like General Patton and says, “We go.”

The sauce is bubbling; she’s browned the veal, added the tomatoes and onion, flung her sea salt. It is a plain but sweet scent, and I lean over the pan and drink in the fragrance. Everything I want to learn is in that sauce, and all I want to know is how to bag the essence of something, in this case ground veal, and skip the clutter that obscures it.

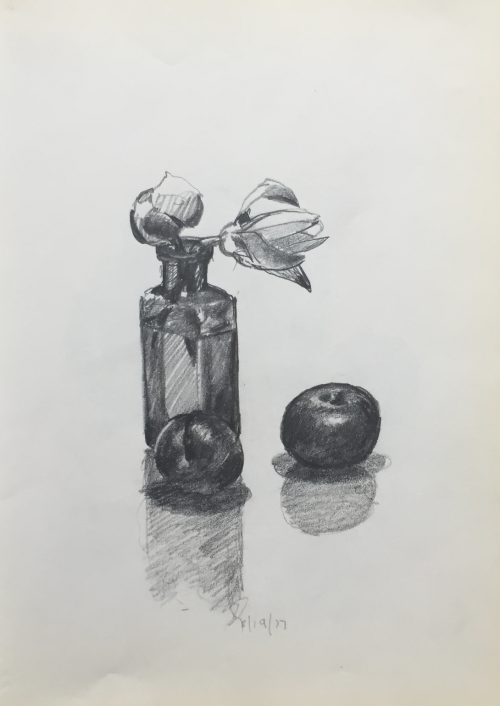

The vase sits on an ancient Italian chest in the living room next to an Oriental head expressing some kind of serene state. The vase has a rough surface—one that announces the clay—and as I sit on the sofa facing it, I want to reach over and rub it. The vase holds a clutch of lilies and one pink flower. Each day the bouquet changes slightly, as if someone were watching it and adjusting it. But these changes are very low-key. They never command attention; they are simply something to be discovered. Neither Victor nor Marcella Hazan ever mention the bouquet. Now and then I see them fiddle with it for a brief moment, just the slightest kind of alteration.

Victor holds his wine-tasting and cheese-tasting sessions in the living room, and so I watch the vase every day. He is passionate about Italian wine and about wine, period, since he sees it as a thing that is always local when at its best and never finished. “Wine,” he stresses, “is alive.” There in the bottle, now on your tongue. Alive. And it is, when properly made, of a place, not a country, but a place: a hill, a valley, the imagination of a vintner. The same with the cheese.

We ask, “How long should wine breathe?”

He says, “I don’t decant wine. If air were good for it, why do people put it in bottles with a cork?”

I think, Thank God he’s dispatched all that fuss and bother.

So he leads us through the wines and cheeses of the Veneto, the Piedmont, Lombardy, Tuscany, and so forth. We twirl, sniff, and drink. I listen. And watch the vase and the flowers live on, just like the grapes in the bottle.

She was born to a prosperous family in Cesenatico, Italy, a small coastal community in Emilia-Romagna, that chunk of the Italian north that has showered us with Parma hams, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, and balsamic vinegar. Her father somehow wound up with his family in Egypt, where at age 9, Marcella fell while running on the beach and broke her arm. Poor treatment resulted in paralysis and forced a return to Italy, where she went through three operations in five years. For the rest of her life, her right arm and hand would be of limited use, a limb better suited to holding a pack of Marlboros than a lit cigarette. But her mother told her she could do anything with her arm. So she got doctorates in biology and the natural sciences and then met Victor, who had been born within ten miles of her village and wanted to be a writer. Jewish, he’d gotten out of Italy before the war and been a furrier in New York City. In 1955 they married and went to New York.

Besides loving literature, Victor loved food, and so one day Marcella Hazan stood in her apartment kitchen in New York and cooked her first meal: chicken with white wine, garlic, and rosemary. And at that moment, she discovered something about herself that her career in science had not revealed to her: She could remember everything she had ever tasted. She became intrigued when she realized that the flavors themselves pointed to the commonsense ways of preparing and cooking ingredients that would reproduce those dishes. “Eventually I learned that some of the methods I adopted were idiosyncratically my own, but for most of them I found corroboration in the practices of traditional Italian cooks. What mattered was that the taste of what I cooked began to correspond to the flavors stored in my mind during my first three decades of life in Italy.”

“When you run a lab experiment,” she explains to me, “all you get is a result. When you cook, you get dinner.”

What she’d done was drift from the place of the gifted (say, someone born with perfect pitch) to the place of genius (say, someone who has to reinvent the world to suit himself, like Albert Einstein in the Swiss patent office). She did not simply hear recipes or learn recipes, she recalled meals and reimagined them and made them her own. Which is why in her long career she has only really created six cookbooks.

Once she started cooking Victor supper in the ’50s, there was no place to stop. (“When you run a lab experiment,” she explains to me, “all you get is a result. When you cook, you get dinner.”) And yet she did not sit down and decide to make a career in food. Instead she took Chinese-cooking lessons, and her classmates discovered that she knew how to cook Italian and asked her for lessons, and in 1970, Craig Claiborne, then food guru of The New York Times, called, and she brushed him off, since she had a hard time back then understanding English over the phone, but it got straightened out, he came over for lunch, wrote her up, and the rest is fame, fortune, and some cookbooks.

She said not so much garlic, no, it’s not just about tomatoes, and while we are on tomatoes, forget about the sun-dried version, because they’re overused, and if you buy grated Parmesan in little canisters at the store, buy sawdust instead, because it’s cheaper and tastes the same.

At age 46, Marcella Hazan finally appeared on the American culinary horizon.

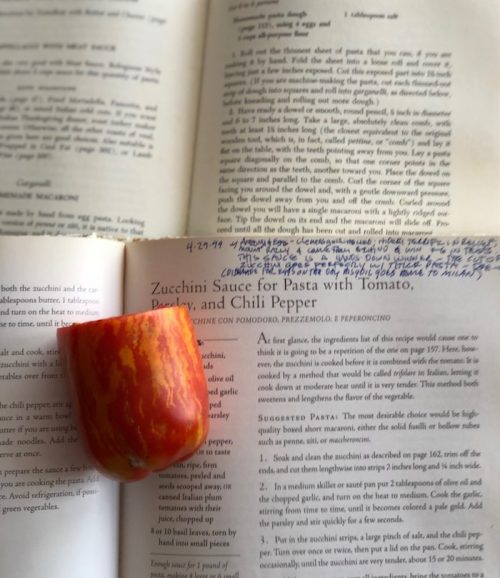

You have to understand drunken pork to get some notion. I stumbled on the recipe (page 419 of her first book, the sacred Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking) and dove right into it, because I love to guzzle red wine and because the book noted, “This tipsy roast cooks at length in enough red wine to cover it, achieving extraordinary tenderness and acquiring a beautiful, lustrous, deep mahogany color.” I went out and got an oval pan (“just large enough to contain the meat snugly”), browned the roast, added grappa, poured on the red wine, tossed on the dash of nutmeg, then let it simmer forever, until the wine cooked down to a syruplike sauce and the loin was tender. And every time, I screwed it up—either the roast got overcooked or the sauce was thin. I thought, Hell, maybe the problem was sampling all the reserves of red wine I had at the ready to cover the roast.

To stand in a room built in 1525 and tell Marcella Hazan you were a slave to a recipe, even one she published, would be to admit you understood nothing, nothing at all.

So now I am standing in the kitchen, and Marcella Hazan has browned the roast, and she tosses in some grappa, and I notice, My God! She’s using a big, round pan; it’s going to take a tanker full of wine to fill it. She adds maybe an inch of wine and puts the lid on tightly.

I say, “Hey, aren’t you supposed to cover the roast with vino?”

She looks at me as if I were an idiot and explains, “That would take too much wine—can’t you see that?”

And I almost say. “Wait a minute, but your recipe says….” And then I realize such a statement would mean truly flunking the course; that to stand in a room built in 1525 and tell Marcella Hazan you were a slave to a recipe, even one she published, would be to admit you understood nothing, nothing at all.

As she had earlier barked at us, “The most important ingredient in a kitchen is common sense.”

I feel like I’ve recovered my sanity, thanks to that whack from her culinary Zen paddle. And I smell the pork roast and wine in the air and lament all the booze I squandered back home.

I’m rolling out the gnocchi—a long, thick strand of dough for potato dumplings—and Marcella is eyeing me like a hawk, and then I hear the battle cry—whack goes the Zen paddle. “Chuck! Chuck! Not so hard. Caress it gently, think it is a blond!” So I think it is a blond, and my pressure becomes smooth, caressing. I look over, and my mentor beams. She really means it. What other cookbook writer has confessed that she will “yield to the temptation of a recently caught fish, glistening and bright-eyed,” or has talked about “the allure of glossy young zucchini”? That is why, whenever I see the row of Palladio’s classically balanced churches lined up like ducks on Isola della Giudecca, I think of Marcella’s struggle to contain her passion for food, her love of taste sensations, within the confines of a pan and a recipe.

For the Hazans, making a living is not the same as living a life.

And that is why I keep watching the vase of flowers on the old chest. Each day the blooms and stems vary slightly, a subtle change like a faint breeze makes within the calm of a forest, but a change nevertheless. This change is always right; I can feel that, and yet it is so restrained. You have to look damn hard to realize something is changing.

Victor sits in front of the vase and flowers each day and teaches us those wines and cheeses and slowly convinces us that place matters, period, above all, and that it is better for a wine or cheese to be from some specific place than to be, say, the best wine or cheese in the world. For those of us trained on Velveeta and Big Macs, this is some notion. But slowly I come to accept it and believe it. As the days go by and the flowers move and slowly dance, I become the opposite of the sophisticate at home in the world. I sink into the joys of being provincial and insisting that my hooch and my chow smack of dirt, sun, and air peculiar to some valley or plot of ground. “Better here than everywhere!” becomes my new battle cry.

Out of the corner of my eye, I see a man grab an eel from a pile, toss it onto the counter. The eel wriggles free for a second, and then the man lops off its head with a knife. In the pescheria di Rialto, the fish market of Venice, stuff is fresh—either alive and moving or barely dead. There are the scents and colors and shapes of sea creatures. But that is not what catches the eye. It is the handmade signs saying NOSTRANI (“ours” in Italian). The same signs dot the neighboring vegetable market. Everything that says NOSTRANI costs more than everything that is from afar. A tiny shrimplike beast (schile) that says NOSTRANI costs more per kilo than salmon from Norway. These people really do put their money where their mouths are.

I gorge on smells and forms: a pig’s head on a pike, a pile of radicchio, a seasonal mostarda (a preserve of mustard and quince) that is available for only a month or so each fall. I remember savoring a bottle of wine at dinner and discovering that the vintner corked only 3,000 a year. I sniff the air and let my senses tug me back into a tribal world, that place of ardor, desire, lust.

Once, when Victor was instructing us in the nuance of wine, Marcella appeared in the doorway. He looked up, she fluttered her eyes, and then she glided off. They’ve been married forty-nine years, and the food has been pretty good, too.

She was in the sciences, he wanted to be a writer. He went into furs, then advertising; she tried lab work. But there was always this kind of hunger. For the Hazans, making a living is not the same as living a life. She is a woman who needs to create, and so, after the lab, she tried a solution from Japan. For four years, Marcella Hazan studied ikebana, Japanese flower arranging. Ikebana is about simulating the natural world with a few fragments; it is about getting to the essence of things.

Then cooking intervened.

I don’t want to make too much of cooking. It is not a mystery: it is a simple, clean thing. And that is what she has forced the world to pay attention to—the fact that all you need are a few pans, a good knife, and an appetite.

Marcella Hazan says to me, “You have to capture the way the stem and flower hold themselves to the sun.” And I can hear the voice that commands her kitchen—I suspect the same voice came from Cézanne at times or from Hemingway in his sober moments. Imagine a form like a perfect sentence, a perfect bar of music, a perfect work of art. Imagine that a perfect risotto or grilled fish is a kindred achievement. Something close to the bone, something you feel without actually being aware of it. Imagine food as a fast car on a night highway with the windows down, and you have no sense of driving or of motion or of self but simply fly down the black tongue of road. And all this comes not from trickery or illusion but from stripping things down to a clean and true surface. And then imagine you are also a trained scientist and you make exact notes, and so when you come out of your fugue state you can perfectly write a recipe without a single step missing. Now put the pedal to the floor and cook.

The last supper is now upon us. The menu has a first course of risotto, then tagliata di manzo with an olive oil, garlic, and rosemary sauce and some vegetables. For dessert, we will have monte bianco, a chocolate chestnut cake from the Italian Alps. The wine is good enough that I cannot remember its name, just the taste. Like everything about cooking, the meal will be temporary—we will eat our creation—and permanent. We will remember and savor.

A few petals have fallen off the bouquet in the vase on the old chest, and the effect is perfect. Marcella is kind of sad. Each day we would cook and then sit at the big table and have a feast. She’d just pull up a chair, nibble, and have a smoke as we stuffed ourselves. Today, she eats. Almost three decades are ending; she and Victor are giving up the place in Venice and going to Florida to be near their son, a rising cook in the Italian culinary world. She tells me she has mixed feelings. And an appetite.

I have one feeling about it all, and it is contained in the tagliata di manzo, the sliced grilled beefsteak, a dish as simple as lust. Put a third of a cup of olive oil and about a dozen medium whole garlic cloves in a pan over medium-high heat. Stir it a little until the garlic turns a pale gold like Marilyn Monroe. Turn off the heat, add two sprigs of rosemary, and toss them over a couple of times. Now get a cast-iron skillet and put it on the stovetop at a very high heat. When it’s real hot, put in, say, a two-inch-thick boneless steak, a rib or a strip, and let it sear for a moment. The meat should sizzle instantly and smoke quickly. Now turn it over and sprinkle the seared, dark brown side with salt and give the other side two or three minutes. Take it out, put it on a cutting board, and cut slices a half-inch thick. The meat should be very rare, we mean damned rare. Now turn the heat under the olive oil back on, to medium. As it’s getting hot, put in the slices along with any juice on the cutting board and cook and flip them for about a minute. Give ’em a few liberal grindings of black pepper. Now put the slices on a warm platter, pour the oil over them (holding back the garlic cloves and rosemary). Pour yourself a glass and eat.

I don’t want to make too much of cooking. It is not a mystery: it is a simple, clean thing. And that is what she has forced the world to pay attention to—the fact that all you need are a few pans, a good knife, and an appetite. After that, it is about fresh ingredients and respect for their flavors. That’s why she had a huge refrigerator and freezer ripped out of her new condo in Florida—if you like fresh food, why in the hell would you have a machine to store it in while it gets old and stale? So she sits there quietly beaming at her table as we eat and drink, the last of the thousands of students into whose heads she has tried to talk some sense. I’ve gone out and bought, in homage, a swivel-headed vegetable peeler just like hers. As a graduation present, she’s given me an apron and a small wedge for busting up Parmigiano-Reggiano. I look over at the flower arrangement with all its simplicity and chew on another chunk of seasoned beef.

School is over, and you have your diploma in your mouth. That’s what it is about. Taste yourself.

[Photo Credit: AB; Illustrations by Fred Garbers]