The horrible days in May, as they came to be called in Glen Ridge, actually began on the first day of March on a baseball diamond owned by the borough, a New Jersey bedroom community 15 miles west of Manhattan. It was still a few weeks before Glen Ridge High School’s champion baseball team would begin official practice, but on that blustery late-winter afternoon the field was dotted with teenagers putting together a game on their own.

Though most of these boys were not actually on the baseball team, a few were. One was Kyle Scherzer, who was captain and center fielder for the Glen Ridge Ridgers. He was also co-captain of the school’s football team, a position he shared with his twin brother, Kevin, and his friend Peter Quigley, who were playing ball that day too.

According to both official and informal reports, a 17-year-old girl was watching the boys play ball that afternoon. She had known some of the boys since childhood. Although she was attending special-education classes in the West Orange school district, she played sports with teams in Glen Ridge, where she lived. Some students say that this fairly pretty girl with the pageboy hairdo often hung around where boys were playing. She was known, in the vernacular of high school boys, as “outgoing.”

When the game ended, 13 of the boys, it is charged, headed back to the Scherzer home. It was a short walk from the park to Lorraine Street, where the Scherzers live in a small, neat, wood-shingled house with a partially finished basement rec room. In the only interview the girl would give, she remembered that the boys said, “Oh, do you want to go to a party?” Later she would correct herself: “No, not a party. They said, ‘We want to talk to you. We won’t hurt you.’ I said, ‘All right.’”

What happened next that afternoon in the basement of Kevin and Kyle Scherzer’s home is the subject of an official investigation being prepared by the Essex County prosecutor’s office for presentation to a New Jersey grand jury. What happened next that day in March would, in the tiny world of Glen Ridge High, ignite into a blaze of gossip and rumor that later spread through much of the adult community as well. What is alleged to have happened next at 34 Lorraine St. would become national news and, as one resident would describe it, “a fire storm” in New York’s local media, which often overheat already heated events.

Early on a Wednesday morning nearly three months after that scrub game, police showed up at the Scherzer home to arrest Kevin and Kyle. The 18-year-olds were charged with aggravated sexual assault and other related crimes. In less legalistic terms, the boys are charged with raping the 17-year-old girl with a broomstick and a miniature souvenir baseball bat. Their friend and teammate Peter Quigley is charged with conspiracy and aggravated sexual assault, though the Essex County prosecutor claims Quigley’s role was more that of cheerleader than participant. Two other boys were charged with conspiracy, aggravated sexual criminal contact, and aggravated sexual assault. As juveniles, they have not been identified publicly.

There were eight other boys in the basement that day, the prosecutors say. None has been charged with anything, although they have all been questioned by investigators and may have to testify if their friends go to trial. Students at a high school that prides itself on athletic participation, these boys only watched.

Long before the horrible days in May, if the name Glen Ridge found its way into print it was usually in stories about “quaint” real estate. And quaint it is. As the annual Memorial Day parade crept down Ridgewood Avenue, the volunteer fire department rolled by in shiny engines; the ambulance crew blew the siren; Cub Scouts and Brownies marched by with incredible imprecision. Every now and then an earnest parent jumped into the flow, pointing a video camera. But on this Memorial Day, the amateur video crews were being watched by professional ones, there to record the town’s mass reaction to the now-famous rape story.

Ridgewood Avenue, a wide, tree-lined street that runs the entire 3½-mile length of Glen Ridge (which is six blocks wide), serves as the town’s symbolic core, all it aspires to be. It is a prosperous and tasteful street, with big, neat houses set discreetly back on manicured lawns—that sell for close to $1 million. Waiting at the parade’s terminus, standing in front of a war memorial and a flagpole on the grounds of the town’s large, tile-roofed middle school, (Glen Ridge Mayor Edward M. Callahan Jr. was preparing to deliver perhaps the most important speech of his life. Certainly, for this part-time politician who heads a municipal machine of 67 people, it would be the most public. The Memorial Day speech after the parade in Glen Ridge usually consists of so many well-worn platitudes about heroism and duty that it is forgotten before the first gin and tonic is mixed that afternoon.

But over the previous week this town of about 8,000 people, 4,400 borough-owned shade trees, and 666 gas lamps had been plucked from its comfortable, near-deliberate obscurity and held up as an example of small-town moral corruption, misplaced values, insular intrigue, and sexual perversity. Mayor Callahan looked grim.

“We, the thinking people of this community, categorically reject the concept of universal guilt.”

As he stepped up to the microphone, Callahan admitted that his Memorial Day speech usually dealt with the usual Memorial Day topics. “But,” he said, “today is not an ordinary Memorial Day in Glen Ridge. Today marks the end of a seven-day period during which this community has seen the filing of complaints against five young people who are residents of our town, alleging serious charges of aggravated sexual assault, unofficial and unsupported allegations of impropriety and cover-up in official investigations, and a literal invasion by the national news media.

“We have all experienced a range of emotions,” the mayor told the townspeople. “Repulsion, anger, deep concern for the victim of the alleged act and her family, as well as similar concern for the parties who have been charged and their families, a serious and justifiable concern regarding the impact of these events on the children of our community, and a clearly discernable feeling of guilt and, somehow, embarrassment over how we are now perceived by the outside world.”

During his speech, the mayor was applauded when he attacked the invading media. He was applauded after he listed the many accomplishments of the town’s youth. But he was applauded longest for saying, “We, the thinking people of this community, categorically reject the concept of universal guilt.”

Whether Glen Ridge was guilty or not, it would have been more readily absolved, perhaps, if nearly three months hadn’t passed between the alleged incident and the arrests. If, as the story unfolded—and some of the story behind the story was told—it hadn’t become clear that during those months whispers about a sexual assault had gradually turned to outright talk. And if so many of the boys accused of the crime, both as participants and observers, hadn’t been members of the same revered jock clique—so that it was easy to suspect that unbelieving or incredulous adults would find it convenient to look the other way—Glen Ridge would probably have remained a quaint little town known mostly for its interesting houses.

In the week after the arrests of the five students, it was hard to tell what made protective Glen Ridge residents most upset. Was it that five boys from the town could have done such a thing? Was it that the media reported the sensational elements of the story with headlines like the Post’s “Town of Shame”? Or was it that some other residents—most visibly a history professor named Steven Golin—were damning Glen Ridge so loudly? “For some people in town, choosing between baseball and football players and a retarded girl wouldn’t be that difficult,” Golin said. “They’d choose the athletes and their feelings and future.”

Glen Ridge, after all, had long been a “special” town. Set on top of a long slope that rises up from Newark Bay, it is light-years away from urban blight. In feel and look, in fact, Glen Ridge is significantly more comfortable and pristine than even its own comfortable and pristine neighbors—towns like Bloomfield, Montclair, and East Orange. “These are the types of incidents which until [recently] people in the community only saw on the nightly news,” says Rev. Randall Leisey, pastor of the Glen Ridge Congregational Church, which sits across Ridgewood Avenue from the high school. “The quandary is, it happened here and it’s getting splashed in the media and it’s making the community look bad.” One young woman recently home from an Ivy League college put it bluntly: “Rape in Glen Ridge means a black kid from East Orange.”

Somewhere along the line the town lost its knack for keeping secrets, and the alleged assault was one big secret.

But during the horrible days of May, other chinks in the suburb’s veneer began to appear. The most troubling was the story of an incident at the high school, where vandals raised a flag emblazoned with a swastika and scrawled anti-Semitic graffiti on classroom windows—but only, it was reported, on the windows of the classrooms of Jewish teachers. What bothered some residents who spoke of the incident in public meetings that were supposed to be reserved for discussion of the alleged rape was that the anti-Semitic vandalism was dismissed so quickly and so quietly.

But somewhere along the line the town lost its knack for keeping secrets, and the alleged assault was one big secret. What really bothered people was that all of the boys accused were Ridgers—the nickname of the school’s teams that students have appropriated for the elite group of kids at Glen Ridge High. To be a Ridger in Glen Ridge signifies belonging. The ticket to popularity can be good looks or family wealth. But most important is star-jock status. This doesn’t make Glen Ridge High unusual; in fact, it would seem a perfect training for the ways of real life.

Soon after the arrests were made, enough students—and later their parents—complained of the special treatment given the jocks of Glen Ridge that it became obvious that some long-held resentment was bubbling up. Leisey says, “I’ve never really seen [the special treatment], but obviously it was something that was irritating people, and people said it had been a problem for years.”

Indeed, a year before the arrests of the three senior athletes, the night the Ridgers baseball team won a championship game, Glen Ridge’s then-star athlete was reportedly caught with a keg of beer in his car. He was not suspended from school, and during town meetings after this year’s arrests, students and parents brought up the incident as a prime example of the preferential treatment afforded Ridgers, jocks in particular.

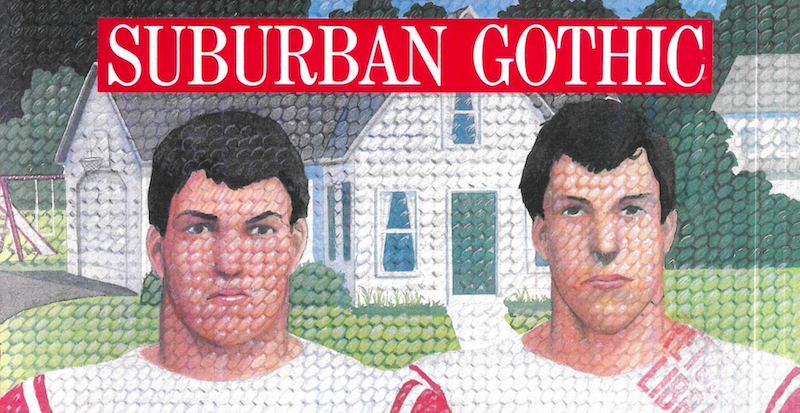

It was into this environment that Kevin and Kyle Scherzer emerged in their junior years. Tradition virtually assured that, by making the starting team of the football squad, they would be picked as co-captains the next year. Likewise, they became part of the high school’s self-appointed elite. They would also, in time, become symbols: the image of the white, middle-class, suburban, high-school football stars being led manacled into a gritty linoleum-covered Newark courtroom to face criminal sex charges was a tabloid dream story. The plot looked like Fast Times at Ridgemont High, as rewritten by Tom Wolfe.

The fact was that Kevin and Kyle Scherzer were, in their small world, Masters of the Universe. “Look at them,” says one young Glen Ridge woman, “they’re so pretty. These boys had everything.”

While the Scherzer twins had the looks and the athletic ability, they were not from a particularly wealthy family, although the tabloids would sweepingly characterize all of Glen Ridge as affluent. The house at 34 Lorraine St., where J.E. Scherzer, a supervisor with the Otis Elevator Company, lives with his family, is relatively modest, like most of its immediate neighborhood. It might sell for around $200,000. And the Scherzer family is big: Kevin and Kyle are the youngest of five children. Two older brothers played football at Glen Ridge before going on to play at small colleges.

The Scherzer family may have had great sports expectations, but the Glen Ridge football team was simply not very good by the time Kevin and Kyle became captains. It didn’t much matter. “There’s no doubt about it,” says a Glen Ridge parent who coaches sports, “the football team is still the social event on a Saturday afternoon in the fall.” Seated on their red-and-white Ridgers stadium cushions, parents and students watched Kevin and Kyle Scherzer lead the hometown team to an unimpressive 2-7 record in 1989.

Though they are identical twins, the Scherzer boys do not look it. The resemblance is strong but not uncanny. As he moved into his teens, Kevin kept up a weightlifting regimen that made him big and broad. Kyle was a jock but not nearly as obsessive about the weights.

“Kyle was captain of the baseball team,” says one local sportswriter, “and whenever I was at games, Kevin would be in the stands—you know, kind of strutting around.

“He’s always wearing those muscle T-shirts. And those real flashy sunglasses. And, I don’t know how else to describe it, he’d just strut around, like he should be the center of attention.”

Even their junior yearbook photos show two very different boys. Kevin stares into the camera confidently, looking a bit like Rob Lowe, his hair stylishly wet and spiky. Next to him on the page, Kyle looks shy and unsure of himself. But while less aggressive than his brother, Kyle could be talked into jock posturing. As baseball season began this year, he and his senior teammates dressed in tuxedos—with many donning Tom Cruise-like Ray-Bans—and posed with their baseball bats for an unofficial team photo. Their coach dubbed them the Hit Men.

But it was another picture of Kyle that may have helped lead to the trouble he’s in now. During the semester in which he was arrested, Kyle started working with children at a local day-care center. The Glen Ridge Paper happened to choose a picture of Kyle with a youngster to run above a front-page story about the program; after the story ran, a caller to the paper said that the young man in the picture was one of the boys who had assaulted a girl. And other news organizations probably got calls, too.

Neither of the Scherzers was a particularly good student. “They were getting through school,” says one parent, “but that’s about it. In terms of college, neither boy had really been accepted anywhere. They were marginal students. They were maybe going to go to the local community college, which really only requires a high school diploma.”

The boys simply had other skills. “Kyle is a natural athlete who helps himself by also being a smart athlete,” says a local sportswriter who often watched the brothers play. “Kevin tended more to throwing his weight around.”

After the arrests, students in the school recalled that by this time some of the boys involved were calling themselves “A-number-one rapists.” They bragged about it.

The brothers’ sports styles carried into the rest of their lives. “There’s no question about it,” says a former classmate and teammate, “Kevin is the sort of guy who’s very aggressive. He’ll tell you what he thinks. He’s very up-front with things. Kyle’s more laid-back, kind of quiet.”

The Essex County prosecutor says that on that first day of March in the basement, Kyle Scherzer spread a lubricant on a broomstick and a miniature baseball bat.

Then he handed them over to Kevin.

The Scherzer twins might well have cruised on through graduation if it hadn’t been for a boy who straddled the line between Ridger and outsider.

Charles Figueroa is a big kid who played lineman with the Ridgers football team. He is black, one of the few blacks in Glen Ridge High—or the entire town. He reportedly receives some special instruction so, in day-to-day school life, is a bit out of the mainstream. He worked in the Glen Ridge High audiovisual room.

According to his lawyer, Ronald Kuby, a civil rights specialist who works in the office of William Kunstler, Figueroa was approached by some of the boys—team buddies of his—who had been at the March 1 “party” in the Scherzer home. They wanted Charles to videotape a second “party” with the same girl. Figueroa said later, “They were going to get her to do it again. They wanted me to tape it because I work in the AV room. They were laughing about it. They thought the whole thing was funny.”

The idea that the assailants were planning not only to assault the girl again but, in some sort of Rob Lowe/Robert Chambers kind of way, to record it added another lurid detail to an already juicy story. After the arrests, students in the school recalled that by this time some of the boys involved were calling themselves “A-number-one rapists.” They bragged about it. Even the school janitor reportedly knew about the incident.

Figueroa’s lawyer says his client refused the request and then—sometime in the first week of March—told one of his teachers. The teacher apparently did not tell school officials.

Glen Ridge officials have maintained throughout that they first heard about the alleged attack on the afternoon of March 22. Charles Figueroa reportedly said something about the boys in a classroom, and this time the teacher told the principal. Michael Buonomo says he then called the student into his office and asked for details. Then, he says, he called the Glen Ridge police.

The Glen Ridge police usually don’t have a major criminal investigation in progress. After all, this is the kind of town where area residents know they should obey the speed limit. And it’s not unusual for a uniformed officer to help pedestrians cross Glen Ridge’s busy intersection.

Two investigators showed up at the school that afternoon. One was Lieut. Richard Corcoran. Buonomo says he told Corcoran and the other officer what he had heard; they told him that because whatever happened happened off school property and after school hours, it was a police matter that required no further school involvement.

There are those who think the investigation might have disappeared entirely if it were not for the long arm of the New York media, most particularly WNBC news.

Over the next month, tensions began to build in Glen Ridge High. The rumor of the attack on the girl was spreading wider and wider. Parents started to hear the stories. Leisey, who has a daughter in the senior class, remembers hearing about the alleged attack sometime early in April (though not from his daughter); he was told by his source that the matter was in the hands of the police.

By the middle of April, according to Figueroa’s mother, Charles had been removed from class and tutored at home for two weeks because he was being threatened by classmates. According to Figueroa’s lawyer, what Charles had told police investigators soon became public knowledge among the Ridgers. And at a public meeting after the arrests, one school administrator would refer to Figueroa as an “informant” before correcting his description.

Glen Ridge Police Chief Thomas Dugan said that the investigators worked on the case from March 22 until April 12, when they passed the investigation to the Essex County prosecutor’s office. It had taken three weeks, he said, for Lieut. Corcoran to find out that one of the boys in the Scherzer basement on the day of the assault was his son Richie.

There are those who think the investigation might have disappeared entirely if it were not for the long arm of the New York media, most particularly WNBC news. On Thursday May 4, managing editor Michael Callaghan received an anonymous call. The caller gave details of a sexual assault by a number of boys in a house in Glen Ridge. Callaghan says that over the next few days he called numerous Glen Ridge municipal and school officials but “ran up against a brick wall” and could only get confirmation that an investigation was under way. Finally, Callaghan says, he sent a young field producer to interview students at the high school about what they knew. Convinced that there was an incident that was being talked about, he sent reporter John Miller to the town.

As it turns out, it was Richie Corcoran, the lieutenant’s son and another member of the school’s jock subculture, who came to personify the attitude that residents like Steven Golin would find so despicable When a Channel 4 cameraman and producer showed up on the school grounds on Tuesday May 23, they asked Corcoran about the alleged incident. On camera Corcoran said, “She wanted it.” He was also filmed giving the finger to the camera. And there is footage of him making gestures that seem to indicate masturbation and fellatio. The secret was out, and it made great television. “What made our town look bad,” said one parent in the week after the arrests, “was those obscene gestures on TV.”

The report WNBC ran that Tuesday night at 6 and 11 p.m. dealt with the rumors that would not go away. Though the story Miller had was sketchy, the basic details were correct. The next morning, the Scherzers, Peter Quigley, and two juveniles were arrested.

Police officials maintained then (and still do) that the arrest of the boys one day after the WNBC broadcast was coincidental. But some Glen Ridge residents said they suspected a cover-up by the Glen Ridge police department. “For more than a month kids and teachers knew the sordid details—so why wasn’t anything done?” Marcia Mann, a mother of a high school girl who lives on Ridgewood Avenue, asked a reporter from the Post. “Because everyone was afraid to say the names,” she continued. “They’re afraid of the police department. This was a cover-up.”

Glen Ridge officials dismissed any allegations that they had tried to make the incident go away. Chief Dugan explained that with so many suspects, it simply took a while to interview everyone. The Essex County prosecutor’s office initially dismissed allegations of cover-up, too, but within a week it announced that county officials would look into the way Glen Ridge police handled the complaint. They will say nothing now. At the press conference on the day of the arrests, Chief Dugan was flip. “Sometimes,” he said of the investigation, “it doesn’t happen like it does on television.”

As the residents of Glen Ridge perceive it, for about a week after the arrests, everything in their town seemed to happen on television or in the papers. The big-city dailies splashed the story of the arrests. Some did follow-ups and then moved on. Time picked up the story but only to use Glen Ridge as yet another example in a national trend of teenage sexual violence. Newsweek did a cursory recap of the story and explained the intense media coverage as the New York press’ overcompensation for its obsession with the racially charged Central Park gang rape of the jogger.

The day after the arrests, metropolitan-area news teams had virtually enrolled in Glen Ridge High, and an eerie mood of fear and retribution set in.

Though the comparison of the two groups of teenagers from very different places is facile, and wrong in many ways, it made for powerful television. In almost every television broadcast, the story was led off with footage of Kevin and Kyle Scherzer and Peter Quigley entering the Newark arraignment. The boys, roused early, were dressed casually in T-shirts and sweats. The Scherzer twins had draped identical red-and-white Ridgers team jackets over their wrists to cover the handcuffs. The students did not recoil from the cameras as some of the Central Park suspects had. They were good-looking white boys who hardly looked contrite. But neither were they really arrogant. The look on their faces was more like surprise—that this could happen to them, that they could be caught.

By the day after the arrests, metropolitan-area news teams had virtually enrolled in Glen Ridge High, and an eerie mood of fear and retribution set in. At a school meeting to talk about the arrests, a group of the jock clique is said to have threatened other students and walked out of the room en masse. Steven Golin’s son Josh, who had been elected class clown, was quoted in a few newspaper and television reports as saying that the boys involved should be punished. Later that week, he reported to Glen Ridge police, his car was vandalized. “He says he doesn’t talk to reporters anymore,” his sister said a few days later.

Glen Ridge residents thought news reports reached their nadir when a girl whose identity was disguised electronically said on camera that she was afraid to walk in the halls of Glen Ridge High because she could be sexually assaulted. But after reporters managed to get into the high school boys’ lavatory and found graffiti that read, “Any jocks who would rape a retard are ——-,” a township policeman was stationed at the high school’s door to ward off the television crews. Still, one station used a zoom lens to tape the school’s annual outdoor party behind the high school building.

It was in this atmosphere of media siege, a week after the arrests, that Leisey organized a community-wide religious service. Though the church has only 850 members, some of whom are not residents, Leisey sent invitations to all 2,300 homes. On that hot and sticky Wednesday night, the church was nearly filled. “We have precedent for one other community crisis in the 13 years I’ve been here,” Leisey said, without a hint of irony in his voice. “It was the time about eight years ago when the town was talking about closing one of the primary schools… and the community was extremely divided at that time over that issue.”

Though the front lawn of the church was filled with camera crews, Leisey predicted correctly that the media show was largely over. “But for us,” Leisey said, “the pain remains. The loss of innocence and the image of a picture-perfect upper-middle-class community comprised of… an educated group of creative people who command higher-than-average salaries and who live in an idyllic setting—that image has been tarnished. And we are left with that. And that hurts bad enough. But… the real tragedy is that some lives in our midst will never be the same.

“We’ve had an incident which has rocked our foundations,” Leisey said. “We have grown in this past week as we have experienced myriad emotions and feelings. We have listened to some craziness and we have listened to thoughtfulness, and yet we are still not sure how all of this came about, nor do we really expect any simplistic answers. But the one thing which we can continue to do is the process which began here this evening. We can pray.”

While Leisey tried to avoid fixing blame and sounding “like a fundamentalist preacher,” his colleague in the interdenominational mass, Rabbi Steven Kushner, chose to lead the group—parents sitting stiffly in the heat, teenagers sprawling across pews—through a remarkable group prayer of confession. Officially, universal guilt was being rejected, but tonight hundreds of Glen Ridge residents joined the rabbi and said together:

For … the sin we have committed against You by malicious gossip, and the sin we have, committed against You by sexual immorality.

The sin we have committed against You by our arrogance, the sin we have committed against You by our insolence, irreverence. The sin we have committed against You by our hypocrisy, the sin we have committed against You by passing judgment on others.

For all these sins, O God of mercy, forgive us, pardon us, grant us atonement!

The almost palpable feeling of goodwill the night of the church service was fading by the next night, when across the street in the high school’s meeting room, hundreds of parents and students showed up to question school board officials in the first of four meetings. Though the meeting was supposed to be a question-and-answer session, it quickly turned into more of a cathartic public ceremony.

It was again a warm, sticky night. The large school gymnasium filled by the 8 p.m. starting time and kept getting hotter. Sitting at a table in the front of the room were school officials, the school board’s lawyer, several members of the town’s volunteer school board, and the president of the Glen Ridge Home and School Association. After introductory statements by all of them, the public microphone was turned on, and the first statement, by resident Marcia Mann, set the tone for most of the evening. Mann brought up Richie Corcoran’s obscene gestures to news cameras and asked why he hadn’t been suspended from classes, as all those arrested had been, under the official explanation that their presence in class would disrupt school routine.

Principal Michael Buonomo answered—or attempted to answer—her question, saying that because Corcoran was part of the investigation at the time, nothing could be done to imply his guilt in any way. And, the principal said, “As the tensions rose in the school—and they did rise—students began to act out in a number of different ways.” Richie Corcoran was just acting out.

Next, a man who gave his name as Eugene O’SuIIivan of Ridgewood Avenue stood at the microphone and said, “The media says it was being hidden. It wasn’t being hidden at all among students. Most of the kids knew more about the incident than I believe Mr. Buonomo knows today.”

The crowd applauded.

“The perception among many people in the school is that jocks could get away with murder,” O’SuIIivan continued. He listed the nomenclature of Glen Ridge high school cliques—jocks, nerds, freaks, burnouts—and said, “Some of these kids really hate some of these other kids.”

Glen Ridge school officials say the bomb threats—and the hate mail—have come from out of state and, possibly, from within the school, prompting officials to have public phones in the high school disconnected.

Over the next several hours the same themes kept coming up. When one recent graduate, Steven Lackey, stood up and defended the alleged perpetrators—“I grew up with them; they are, if you know them, pretty good guys”—people listened. But when he said that he didn’t believe any rape had actually occurred, he was politely told that if he didn’t have a question for the school officials he should sit down.

It was a Glen Ridge High senior, a girl named Nicole Mozeliak, who stirred the group into a quick shouting match. “As a senior,” she said after adjusting the microphone, “I feel extremely stressed out by what has happened. We just sit there and talk about it. I haven’t gotten anything done because my teachers don’t feel we’re ready to learn.

“There have been five not four bomb scares,” she added, correcting earlier statements by a school official. “Yesterday I spent 1½ hours outside the school, then 45 minutes sitting in the gym while a bomb scare was checked. I don’t enjoy getting up in the morning.” (Glen Ridge school officials say the bomb threats—and the hate mail—have come from out of state and, possibly, from within the school, prompting officials to have public phones in the high school disconnected. And, principal Buonomo would say at a later meeting, there was a strong suspicion that the first bomb threat, made on the Tuesday before the arrests and phoned in minutes after a WNBC reporter left without getting any information, could have been made by the news crew, who knew that hundreds of potential sources would soon be out on the street. Channel 4’s Callaghan says, “It’s so representative of the kind of people who are running that school and the smokescreen that they’ve put up around this incident…. It’s pathetic. I feel sorry for the kids who have to go to school there.”)

Finally, Nicole got to her real question. For all that had happened to this small town over the past several weeks, these were still ordinary suburban high school students who wanted a simple and normal graduation. As school officials said time and again, the arrest of 5 students didn’t mean that the other 345 had done anything wrong. Universal guilt had been officially rejected. But if they were not guilty, why were they being punished? Why couldn’t life be normal again? “I want to know,” she said, her voice edgy, “what is going to happen at graduation? Are these boys going to be allowed to attend? Is the press going to be allowed to attend?” After one school district official told her that the matter hadn’t been decided yet—it was later agreed that the five would not return to class and the seniors would not attend graduation—Nicole blurted out, “I’m sick of being lied to and told, ‘Don’t worry about it, we’ll take care of it.’ What is going on about graduation?”

Michael Buonomo then stepped in to answer and ended up in a shouting match with the girl and some people in the audience, which somehow escalated into the principal shouting, “The Ceremony, the Ceremony, the Ceremony!” And then there was quiet.

Though its very foundation had been rocked, Glen Ridge slowly went back—despite the turmoil, the questioning from outside and within—to its normal ceremonies, public and private.

The town meetings ended in the second week of June, and by then, although there was some heated talk, the horrible days seemed long ago. Michael Buonomo even started cracking jokes, telling how so many students had attended group counseling sessions organized by the school that he suspected many were not traumatized but simply trying to get out of their regular classes. Parents laughed. He cautiously defended some of the reporting of the story, telling of the many students who at first sought out camera crews. He hinted at how much he would have liked to have thrown the book at Richie Corcoran for his antics on camera. And he strayed from the cautious official line he held in the early public questioning and told some details of life inside the high school on the first horrible days. “On the day of the arrests,” he told people,”it was as if five students had died.”

Most of the students went back to their normal routines. On the first weekend of June the Ridgers baseball team—even without a few of its star players—won the county-wide championship in its division. At one of the final games, as the media fire storm was burning itself out, mothers sat in the stadium bleachers, passing around sodas and taking in the sun, chatting about the usual things—how to get their sons’ uniforms clean, their husbands’ work. But every now and then they would discuss who had been quoted on camera and who hadn’t, who’d seen Phil Donahue’s show about Glen Ridge. With the horrible days in May over, they could even chuckle over poor Mr. Tantillo, the vice principal and athletic director at the high school, who’d gone on a TV panel discussion and been asked if, as a college jock, he’d participated in any gang rapes. No, Tantillo said, seeming to hunt for the most inappropriate word, “I never had the privilege.”

The graduation ceremony is scheduled to go on as usual on Friday June 23, though precautions have been taken to keep the media as far away as is legally possible. Three prominent seniors will be conspicuous by their absence, but the other 85 graduates will receive their diplomas in an outdoor ceremony, attend a dinner and dance at the Glen Ridge Country Club, and maybe go to the sanctioned all-night party at one of the town’s stately homes, donated by parents who know that otherwise their children would very likely drink and drive. They are normal kids after all. Most of the high school kids were back to talking only among themselves, not with reporters. And the adults of Glen Ridge were returning to their regular routines, although worried maybe that the whole event had made their quaint town look a little less special. “My neighbor is a realtor,” said one resident, “and she just freaked out. All my neighbors say it is going to hurt real estate values. One of the things that Glen Ridge always has been sold on is the school system.”

School administrators have hired a retired judge to conduct an investigation of their handling of the alleged sexual assault and some other, more minor incidents over the past few years. Though he was supposed to begin the review immediately, it was announced in the second week of June that Judge Samuel A. Larner would wait until the Essex County prosecutor’s office finished its investigation. A spokesman for the prosecutor’s office says only that the investigations—both of the alleged sexual assault and of the Glen Ridge police department’s handling of its investigation—are continuing. The Glen Ridge police will make no comment about their conduct in general or about Lieut. Corcoran’s specifically.

There’s no doubt that, as Leisey said, some lives in Glen Ridge will never be the same. On Lorraine Street, the Scherzers appear to have left town, having disappeared shortly after the boys were released on bail. A neighbor says he went over to mow the grass as a favor. He found that someone else had already performed that suburban ceremony.

[Featured Image: 7 Days cover (detail)]