Back at Yale, the professor and Pulitzer-prize-winning author Robert Penn Warren would tell his protégé, David Milch, that the secret to Herman Melville’s poems is that they spin against the way they drive – that is, that even as their narrative thrust carries them forward, they rotate backward, generating a shimmying, ironic tension. This is the sort of English, Milch was saying over lunch one afternoon at the Twentieth Century Fox commissary, that as an executive producer he tries to apply to his hit police drama, NYPD Blue, the season’s simultaneously most praised and maligned series. It’s what lends the program its ambiguous edge. It’s what allows the writers to explore the profound mysteries of race, violence, and love even as the characters – much to the outrage of the Reverend Donald Wildmon’s American Family Association – bare their derrieres and utter such heretofore forbidden-in-primetime locutions as “pissy little bitch.”

Yet as Milch – a stocky 49-year-old clad in a sports shirt, khakis, and Nikes – was expostulating his dramatic theory, it was hard not to think that he wasn’t also talking about himself, that in a sense, he, too, spins against the way he drives. There is, for starters, the paradoxical nature of his vitae. First in his class at Yale, acknowledged as possessing “the finest mind of anybody I’ve ever met” by no less a talent scout than Steven Bochco, NYPD Blue’s co-creator, and winner of an Emmy for his inaugural Hollywood script (a 1983 episode of Bochco’s Hill Street Blues), Milch trails clouds of glory. On the other hand, this is the same man who was expelled from Yale Law School for drunkenly shot-gunning the roof lights off a police car, served time in a Mexican jail, beat heroin, and gambled away vast sums at the track – especially after the big money began pouring in.

It’s not merely the facts, though, that point to a tug of war (one former colleague calls it a demolition derby) going on between life-and-death forces inside David Milch. His behavior is even more revelatory. In the midst of lunch, for instance, Milch briefly pushed his plate aside to huddle with a NYPD Blue production assistant for whom he’s conducting an informal tutorial in literature. The day’s topic: Anton Chekov’s “The Darling.” As Milch warmed to the task, he was once again Mr. Warren’s boy, keeper of the sacred flame, shepherd of the Word.

“The doctor said I should reduce stress, so I made the inference that I had to stop betting.”

But just as one is ready to consign Milch to the ivory tower, he betrays his familiarity with grittier environs, the sort that give NYPD Blue its authenticity, the sort where his onscreen alter ego, Detective Andy Sipowicz (Dennis Franz), would feel at home. Walking across the Fox lot to his office at Bochco Productions, Milch fell into step with the producers of another ABC show. As producers will, these gentlemen were bemoaning the fact that one of their writers was late with a script, stringing them along with the usual excuses. Milch listened politely to his confreres’ complaints – then he was off, relating a far darker parable on the topic of transparent alibis.

“A kid I know,” Milch began, “has a brother who’s a bookie, and back when I was betting a lot, he asked me to use him. I did, and right off the bat I lost fifty thousand dollars.

“Then, I got hot. I won fifteen thousand, and suddenly I couldn’t find this guy. Finally, after I went to his brother, he shows up.

“‘Jeez,’ he said, ‘I’m sorry. My son has got cerebral palsy.’

“‘How old’s your son?’ I asked.

“‘Eight,’ he said.

“‘How long’s he had cerebral palsy?’

“‘Since he was a baby.’

“‘So what you’re telling me,’ I said, ‘is he had cerebral palsy when I was losing all that money, and it didn’t keep you from coming around, but now that I’m winning …’”

Milch had paced his yarn perfectly, tying it up just as the group reached the Bochco compound, spinning it – with its black punch line – against its drive as deftly as if it were an act on NYPD Blue. Cut to commercial.

“For the last ten years, my pleasures have been work and family. I admit I was a heroin addict, but that was long ago.”

The conflicts in his life notwithstanding, Milch has of late been seeking peace. Sitting in his office – a large, Spartan space decorated only by some nineteenth century prints of English thoroughbreds and photographs of his own horses – Milch talked about the event that last fall led to the realization that he had to find “more benign accommodations” for the diametrically opposed forces that pull at him. The pain began in his arms, sharp, insistent, leaving him clammy and sweating. He’d be on the set at NYPD Blue, and suddenly he’d have to stop working. Thanksgiving week, he learned he was suffering from heart disease and soon underwent an angioplasty.

Today, after embracing a regimen of diet and exercise, Milch has shed twenty pounds. “I haven’t had a good meal in months,” he moaned. Equally important, he has given up the racetrack, putting his horses on the block. “The doctor said I should reduce stress, so I made the inference that I had to stop betting.” This said, Milch was loath to attribute all the behavior modification to intimations of mortality. “Angioplasty didn’t change me,” he asserted. “For the last ten years, my pleasures have been work and family. I admit I was a heroin addict, but that was long ago. As Mr. Warren used to say, ‘There is some foolishness a man is due to forget.’”

Still, Milch could hardly be described as a placid soul. Yes, he said, he’s now tedious on the subject of health. Yet with a demonic gleam, he confessed, “I should tell you that next month is the month racing’s great two-year-olds go on sale. Resolves that are easy to make in the winter may not necessarily hold up in the spring.”

Then, spinning not just his drive but his spin, Milch quoted a fabled horse trainer. “As Charlie Whittingham says, ‘Nobody ever committed suicide who has a good two-year-old in the barn.’”

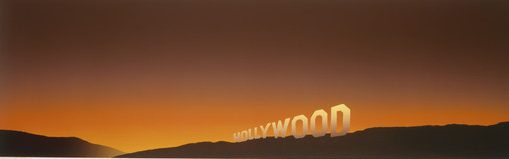

[Featured Image: painting by Ed Ruscha via LACMA]