It was getting into the heart of the Vermont summer, and the air was still and heavy. Resting in a wicker chair on his front porch, Robert Penn Warren, sweat dripping from his sharp, freckled nose like a rivulet running off red rock, gazed into the hazy glimmer of late day. “I think a man just dies,” he said after a while. His voice was harsh and sibilant. “No heaven. No hell.” Tugging a checkered bandanna from a rear pocket of his baggy Levis, he wiped the perspiration from his face. “I’m a naturalist,” he added haltingly. “I don’t believe in God. But I want to find meaning in life. I refuse to believe it’s merely a dreary sequence of events. So I write stories and poetry. My work is my testimony.” Warren’s tone had dropped into a low, croupy register. Limned briefly by the last beams of the sunset, he resembled a statue carved long ago from a hunk of sandstone. He reached for a drink, smiled then said, “I can’t believe I’m talking like this. I can’t tell someone why I write. And I’m sure as hell not going to attempt self-psychoanalysis. But let me tell you a story.…”

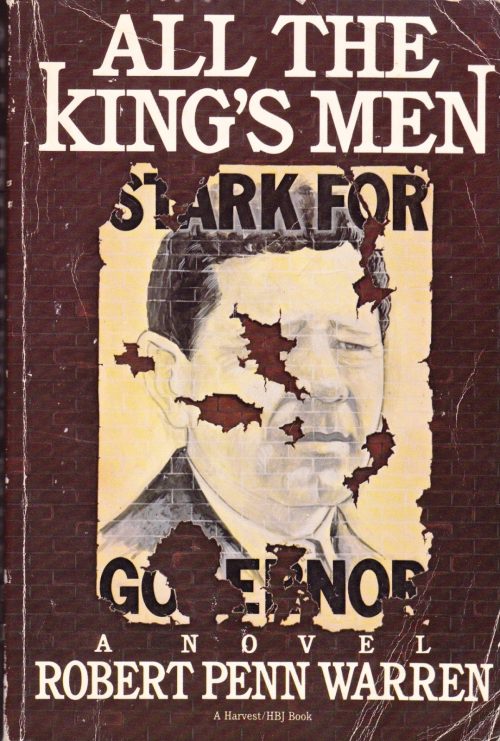

The rhythm of Robert Penn Warren’s life now is settled but not sedate. He rises early, fixes his own breakfast, exercises with a set of barbells kept on the living room floor then dons trunks and a plastic cap and makes the short walk to a bower-hidden swimming hole behind his summer home. He swims nearly a mile in the chilly water, sculling along at a steady, rigorous pace. The clay-bottomed pool is surrounded by ferns and high trees, and in the morning—as thin, miasmic bars of sunlight filter down, dappling the water in tones of emerald and gold—it is Edenic. Here, his body aching slightly from the exertion and his mind free from worries, Warren slips into a creative trance. This is the the hour when the images bloom. The swims are never draining, are in fact less taxing than distance running, the exercise he used to stimulate himself when he was younger. As Warren strokes back and forth through the glittering pond, a poem usually flowers. The past decade has been remarkably fertile. He has revised Brother to Dragons, his epic-length verse drama about Thomas Jefferson’s murderous nephews, and he has written two novels. In 1980, he will publish his fourth collection of poetry since 1966—his most recent, Now and Then, won the 1979 Pulitzer Prize. It was his third. The second came in 1958 for his book of poems, Promises. The first came in 1947 for All the King’s Men, a work of fiction many critics contend is among the finest of the twentieth century.

His swim over, Warren retreats to an outhouse-sized wooden shack poised on the steep banks of Bald Mountain Brook, the rocky creek that meanders behind his home. The structure gives onto a vista of elders and maples punctuated by an occasional white birch. The windows are covered with chicken wire, and even on a hot day cool breezes drift in from the mountains. Inside, sheets of copy paper are stacked sloppily atop a tiny, rough-hewn desk. Leather briefcases are underfoot. A gray, Hermes typewriter rests on a rickety stand. When he is writing fiction or an essay, Warren sits in a Formica chair behind the machine and pecks out words in a rackety, pensive staccato. But if the morning swim has been fruitful, he plops onto a tattered green-and-orange striped canvas beach chair and jots down bits of a poem in a cramped, barely legible scribble. Warren is a diligent worker. On most days, he spends at least five hours in the tiny room that he and his wife, novelist Eleanor Clark, call “The Coop.” Deep in thought, his thinning red hair plastered across his skull and his face flushed from exertion, he looks like an aged fighting cock. He is seventy-four.

Around two in the afternoon, Warren and his wife eat lunch. Her work shack is on the opposite side of the house, an architectural hybrid of a rustic mountain cabin and the jutting, glass geometries of a 1950s vacation retreat. She is first to call it a day, and after stirring around the kitchen, hurriedly dumping bowls of leftover peas and carrots and chunks of beef or chicken into a simmering pot of impromptu stew, she walks to a back window, cups her hands and shouts, “Red, let’s eat.” If his writing is going well, she has to call more than once before he finally emerges, scowling, to tramp up to meet her. Once he has made his way inside, his demeanor softens. Together, he and his wife set the table, feed the dogs—Sophie, a playful mutt, and Frodo, a blind, thirteen-year-old pure-bred cocker spaniel—and pour each other drinks. During lunch, the two usually talk about their children. Rosanna, twenty-six, teaches art history and writes poetry. Gabriel, twenty-three, is a sculptor and boat builder. The Warrens remain young in the way parents still raising a family must. Occasionally they gossip about literature and world affairs, but they rarely talk about each other’s work.

“What distinguishes every writer from the South is that they’ve got a goddamned honed tale sense. One of the reasons Eleanor and I don’t have a television, have never had one, is that we don’t want to lose that.”

In mid-afternoon, Warren wanders downstairs from the dining alcove and takes a brief nap. The first floor of the house consists of three bedrooms fronting a central hallway. Standing in his son’s room several years ago, his mind drifting aimlessly, the opening sentence of his most recent novel, A Place to Come To, “simply popped” into his head. Such unexpected conjuring is not unusual for Warren. More than once when he has been stuck in the middle of a book, he has dreamed whole passages of the story and then written them down the next day. Awakening from his nap, Warren reads a new novel or works of Southern and American history. Sometimes he drives into the woods to visit acquaintances like Mr. Newell, a sparrow-thin maple syrup distiller who owns a large sugar bush hidden behind rock walls. Once a week, Warren hikes several miles up a long, sloping grade to a glacial lake where he often spends an hour staring into the Green Mountains. The Vermont forests—lush and quiet—replenish him. He emerges with many of the ideas and images that later well up in his poetry, poetry that brims with the pulsations of the natural world. A couple years ago, in early fall, he observed wild geese beating south through a gap near the lake. Watching them, he questioned the paths he had followed, the decisions he had made. At least these birds, he wrote in “Heart of Autumn,” respond to the tick of a cosmic clock. But why, he asked himself, had he lived the way he’d lived?

At dusk, Warren, his wife, their children, and any visiting friends rendezvous on a screened porch for cocktails. Warren drinks Campari and orange juice and snacks on radishes grown in the family garden. Occasionally, strains of Louis Armstrong waft into the gloaming from a stereo in the living room. These pre-meal gatherings are almost always rollicking sessions of tale swapping. “You see,” Warren says, “when I first started thinking about writing novels back in the 1930s, people I knew would sit around all night at parties just spinning tales. The South was a terribly rich country then. Rich tale country. Ironically, what made it so is that it was otherwise a horribly impoverished nation. Tale-telling was entertainment. What distinguishes every writer from the South is that they’ve got a goddamned honed tale sense. One of the reasons Eleanor and I don’t have a television, have never had one, is that we don’t want to lose that.” Throughout dinner, usually a simple but hearty feast of baked chicken or roast beef served with good wine followed by tossed salad, the stories continue. Afterword, the forest buzzing in the peaceful night, Warren retires. Sometimes, around four or five in the morning, he awakens briefly, snatching and recording what he can of his dreams. Then he sleeps again.

Robert Penn Warren is an anomaly among American writers. The archetypal American novelist is plagued by angst, alcoholism, poverty, and public indifference to his work. Worse, too many American writers are notoriously unproductive; after one largely autobiographical book, they have little left to say. Unlike their European counterparts, who develop slowly but sturdily, American writers explode after etching fiery, transient paths in the sky. Warren’s slightly older peers—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, Ernest Hemingway—all died tragically. The myth of the American writer is that the work destroys the man, but Warren, the man, has endured. He has produced ten novels—efforts that are at once serious and humorous —fourteen collections of poetry, several critical studies, many textbooks, and a compendium of short stories. In 1930, he contributed an essay to I’ll Take My Stand, an influential collection about his native South.

During the Depression, Warren co-founded The Southern Review, one of the nation’s best literary journals. In the early 1960s, he wrote two studies of race relations in America that largely recanted the stubbornly recalcitrant opinions he held as a young man. He is one of the country’s few Men of Letters, an appellation that usually implies a priggish separation from the moil of life in both a writer’s work and daily existence. Yet Warren defies that stereotype, too. He is successful, happy, critically acclaimed, occasionally querulous, but largely humble, optimistic, curious, and, in his words, “consumed by the thought of the poem I can write tomorrow.”

One late July afternoon, Warren tramped along a new-cut dirt road high in the Vermont hills. He alternately cussed investors who want to use the road to attract vacation housing developments and then, the anger passing, told stories. He wore an old blue knit shirt, drooping jeans turned up at the cuffs, white socks, and hiking boots. He could have easily passed for a cocklebur raconteur back in his hometown of Guthrie, Kentucky. As his voice rasped into the quiet, time and miles slipped by.

“Let me tell you about Uncle Turner,” he exclaimed at one point. “He was the uncle of my old Mississippi friends Bill and Cannon Clark, and he was known for miles around because he couldn’t tell the truth. He would exaggerate even the simplest of stories. He was one of the greatest orators of his time and place.” Warren’s laughter pealed out. “Uncle Turner specialized in funeral and Fourth of July orations. He could talk way down deep. And he could say things like, ‘He was one of the greatest men in our county. His Christian virtue shone as an example for us all.’ Which sounded good when the kinfolks were laying a sinful old geezer in the ground. It was a lie, of course, but that’s why Uncle Turner was so well loved.” Poking a scarred cane before him, a battered straw hat pulled low over his brow, Warren pushed ahead at a brisk pace. “Once Uncle Turner was called upon to dedicate a new damn in Tupelo,” he added. “He was standing at the podium and all these pompous officials were standing up there with him and he commenced with something like, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we have come to christen this great body of water.’ And you know, he was rolling his arms out in great gestures and then he bellowed, ‘This lake will be fifty miles long.’ And he just stopped there. He had looked over at his wife, and she’d been shaking her head in frantic desperation. Well, he thought a moment and then thundered, ‘And it will be two inches wide.’ God, can you imagine it? It’s a true story. Really is.” His eyes watered as he choked down laughter.

Warren has an infectious, ironic sense of humor that permeates his work and his conversations. His almost every tale is twisted to suggest that man is ultimately a folly-filled creature. During the climb up to the glacial lake and back, the stories spooled out one after another. Warren declaimed on a “horrible poet” of the 1800s who advised young men not to go west because “the West is full of debt dodgers, drunkards, fornicators, adulterers, incest-mongers and you shouldn’t join them;” a talented Tennessee newspaper writer “ruined by too much Catholicism and too much Jung” who should have stuck to liquor “because it sure as hell doesn’t ruin you half as fast as the others;” and an old friend, a professional baseball player “who sure God drank himself” out of the majors. “It was a good thing,” he said. “Pitching was cutting into his hunting time back home.” After stopping to spit, Warren recalled how novelist William Faulkner wrote Random House’s Albert Erskine, who edited both writers, that All The King’s Men should not have glorified “that two-bit, low-brow, redneck fascist Huey Long.” A look of amazement lit Warren’s face as he remembered the letter. Then he said, “Damn Faulkner must have been drunk when he wrote that thing. It was so incoherent you wouldn’t believe it.” Making perfunctory stabs with his cane at leaves and rocks, Warren spun out yarn after yarn. It was as if his mind were a Big Top of memories and he a ringmaster calling the past’s players to life. Once one act ended, he ordered the troupers down the ramp way of time and summoned new ones.

“I’ve been saying this for a long time, but I think the whole guts have gone out of the American state of mind. Americans now want it done for them.”

“I can remember my first day as a student at Vanderbilt,” he said trudging toward home. “I was scared, immature, and totally incompetent to do just about anything. I was a terribly young boy, even younger than my age, which was just sixteen I was sitting all alone on the steps of one of the buildings there when this massive hand fell across my shoulder with the force of a tumbling chimney. I turned around, saw a grinning, malicious, oafish face and out of that wet mouth came the words: ‘Boy, there’s only one thing I want to know. Do you ever have evil thoughts?’” Warren parted his lips, flashed his teeth, and brayed.

“The only thing I can be thankful for,” he added, “is that he didn’t give me any time to answer. He introduced himself, said he was secretary of the YMCA and that he wanted to talk with me about Christ. Said that he’d once partaken of whores, liquor, and cussing – which didn’t sound bad to me – but that since he’d been saved he’d stopped.” Warren bunched his cheeks up incredulously. “What’s worse, this fellow had taken to turning in bootleggers because he said Christ told him to. God! That was one tough bugger for Jesus. I remember walking by the track one afternoon. He was a track man. He was winding up to throw the discus. He let it fly and then shouted out: ‘Hey, Red Warren, you’re some sort of poet, aren’t you? Well, boy, that there was poetry in motion.’”

Robert Penn Warren was one of those boys who come out of the Southern hill country with a shock of curly red hair, a freckled face, and hazel eyes. His friends nicknamed him “Red.” Early on, his pioneer forebears had migrated from Virginia into North Carolina; by the time of the War of 1812 they had moved into the undulating hill country of that part of Kentucky about fifty miles north of Nashville, Tennessee. They were modestly prosperous people, and Warren’s father, aside from having interests in land and a small store, was a banker in the village of Guthrie, a tiny place bisected by Tennessee-Kentucky line. As a youngster, Warren saw little of his dad—the elder Warren was constantly at his office—and until he was fourteen the dominant figure in his life was his maternal grandfather, Gabriel Thomas Penn.

Almost from the time he could walk, Warren spent his afternoons with the old man. Grandpa Penn would sit beneath a tree with the boy on his knees and reel off ceaseless stories about the Civil War. The grape shot flew. Sabers rang. Horses, frothing and blood-streaked, carried their Confederate charges into the din of conflict. Fantasies and fascinations of war whirled through Red’s mind like the fragments of glass in a kaleidoscope. Before he could read, he knew the power of a story.

While often absent, Warren’s father also played a part. If it is true that the secret ambitions of a parent—longings often stunted by adult responsibilities—reappear as doubly strong yearnings in a child, the phenomenon applies especially here. On more than a few evenings during his boyhood, Warren’s dad would convene an old-fashioned family reading circle in the living room. They read poetry and histories of Greece and Rome aloud. “My father was a frustrated poet,” Warren remembered. “I’ll never forget the time, when I was twelve, when I was foraging through some bookshelves at home. I found this black book stuck way back among the others. I pulled it out, held it open, and I saw his name.” Warren’s voice cracked with the memory. “I was completely disoriented by the discovery. It was an anthology called The Poets of America, and here were the works of my father included in it. That night, when he came home from the bank, I very unsubtly showed it to him. And he said calmly, coldly, ‘Give me that book.’ We never talked about it again. I think he was ashamed of the poems. He destroyed the book.”

There were other early flirtations with literature, but only in the long perspective of time did Warren realize that forces were moving to shape him as a writer before he was conscious of them. He remembers stumbling across a pile of books in his paternal grandfather’s attic one afternoon and being fascinated by an illustrated copy of the works of the Italian poet, Dante. “I remember that when I found that illustrated Dante I thought how strange, how wonderful that my grandfather had this book,” he recalled. “What is very peculiar, though, is this. Much later, years later, I was poring over crumbling papers at the Harvard library while I was working on a critical study of Herman Melville’s poetry for an edition of his poems I was doing.” Warren’s voice quivered excitedly. “I was sifting through these papers when I found a letter to Melville from a literary society in Clarksville, Tennessee, a small town only a few miles from Guthrie. Well, this letter begged Melville to come to my part of the world, this out-of-the-way country to deliver a lecture. They said no price would be too dear for them. They were reading everything he wrote. The document was signed by people from families that were friends of my grandfather. I wonder if he was involved. He must have been.”

For all the literary intimations that hovered around the periphery of Warren’s boyhood, he really had no active interest in writing, pining instead for the life of an outdoorsman or an adventurer on the high seas. During summer mornings, he searched in the woods for butterflies, arrowheads, rocks, and leaves. His hobby was taxidermy, and his love was baseball. Occasionally, he read from the works of Charles Dickens and James Fenimore Cooper, but never with a yen to make up his own stories. After graduating from high school, Warren sought a commission from the Naval Academy; more than anything, he yearned to be an admiral of the Pacific fleet. One summer night shortly before he was to leave for Annapolis, he was lying on his back behind a hedge looking at the stars. Standing on the other side of the bushes, his younger brother was playfully tossing rocks into the air. He didn’t know Red was resting on the far side, and when he lobbed a large, sharp stone over the hedge it smashed into his brother’s left eye. The damage was severe enough that Warren lost most of his vision in that eye, and he abandoned his hope of entering the Naval Academy. Primarily because he and his father had attended numerous football games at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Warren decided at the last minute to enroll at the small liberal arts school and major in chemistry.

The pivotal moment for Warren at Vanderbilt came early when he was assigned to a freshman English class taught by poet John Crowe Ransom. By the end of the term, Warren’s compositions had caught Ransom’s eye, and the instructor invited him to enter an advanced English survey course. Warren had quickly grown bored with his science studies and had been covertly reading Ransom’s poetry. “His poems set me afire,” Warren remembered. “What I saw in his work was someone making poetry out of my world, the world of the woods and the country.” Ransom’s tutelage proved to be catalytic, as was that of another poet on the faculty, Donald Davidson. Davidson believed that composing clever facsimiles of the classics taught a student more about literature than writing critical essays did. For an entire semester, Warren mimicked the styles of every English writer from Chaucer to Thomas Hardy. Under the two men’s influence, he began writing poetry.

During the 1920s, Nashville, an otherwise insular city, was the vortex for one of the most influential groups of poets and thinkers ever to gather in America. Shortly before the start of World War I, several Vanderbilt teachers, including Ransom and Davidson—as well as downtown businessmen interested in poetry—formed a literary group called the Fugitives. Its credo: “The Fugitive flees from nothing faster than the high-caste Brahmins of the old South.”

Artistically radical, the Fugitives scorned the ancestor-worshipping literature of post-Reconstruction Dixie. Not long after Warren began writing poems, the society’s magazine published a couple of them. At eighteen, he was made its youngest member. “They treated me like an equal,” he recalled. “Except, I said a lot of foolish things and they told me so.” The group met every week, and each session was conducted in a personally friendly but critically cutthroat manner. Warren’s poems had to be excellent to earn an accolade from this bunch. “They could be derisive as hell,” he said. “But more than anything, that process of close analysis taught me how to write.” The group spawned the so-called Southern Literary Renaissance, a movement that ultimately included writers as disparate as Allen Tate and James Dickey. “I’ve never heard of any other thing like it in America,” Warren declared. “We were absolutely wild for poetry.” Warren, especially, was consumed by a passion for literature. He memorized T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland and decorated his boarding room walls with paintings depicting scenes from the poem. By the time he graduated, he had begun publishing verse in The Nation and The New Republic.

After leaving Nashville, Warren attended graduate school at the University of California Berkeley and Yale before leaving for England in 1928 on a Rhodes scholarship. During these years, he lived entirely from fellowship money; the occasional $10 he received for a poem or a review was used to purchase a good bottle of whisky. It was shortly before he left for Britain that Warren began to consider writing fiction. He had scorned novels as “vile, dreadful stuff written by hacks” until he met the established author Ford Madox Ford and the rising young short story writer Katherine Anne Porter. They gradually convinced Warren that the novel was a legitimate literary form. But it was not until Warren arrived at Oxford, where he was lonely and homesick, that he decided to write a story in the hope that the project would help him cling to his pleasant memories of the South. Laboring on his fiction at night, he produced a novella called Prime Leaf, a story of tobacco warfare in Kentucky. The piece was a harbinger of Warren’s later novels, works almost always tied directly to historical events, and it riveted him to the idea of becoming a novelist. After returning from England, he cancelled a fellowship at Yale (“I didn’t have time to write a damn doctoral thesis”) and began searching for a teaching position to support him while he wrote.

Shortly before taking his first job at a Memphis college, Warren made his contribution to I’ll Take My Stand, the volume of essays about the South. The book champions agrarianism as a way of life. Warren’s passions had been chiefly aesthetic until his involvement with the project, but during his correspondences and conversations with a group of Nashville friends who edited it, he began to outline many of the philosophical tenets that would sustain him for most of his days. In numerous ways I’ll Take My Stand is obtusely unenlightened. Yet in spite of the work’s unreconstructed point of view, some of the essays espouse a bold and intoxicating romanticism. The agrarians embraced a Jeffersonian belief in the salubriousness of life on the land; they insisted on the nobility of the individual; they were skeptical of technology. Warren’s piece was called “The Briar Patch.” Liberal for an era in which most southern whites believed blacks should be denied any schooling it now seems racist in its insistence on separate but equal education for blacks. Warren admitted that his views on race “were unfortunate,” but he bristled when defending the general thrust of the book, especially its views on industrialization.

“I’d been very much struck by something that Henry Adams, the historian, said about the test of modern man being how he would deal with the machine. He said the machine would end up riding the man instead of the other way around. I feared that then, and I still do. I think we were really pretty perceptive to attack rampant technology so early.”

On a balmy summer night, his elbows propped on the dinner table, Warren was fulminating on the decadence and decline of the Western world. In between bites of green beans and chicken and glasses of fine, Spanish wine, he excoriated oil company executives, fumbling energy department bureaucrats, and soft-headed jurists. It had been a long, sumptuous meal that Warren’s wife had begun preparing early in the afternoon. Three years ago, Eleanor Clark was partially blinded by the disease macular degeneration. At first, the condition seemed hopeless and was emotionally devastating. Clark had written several books, and in 1965 had won the National Book Award for her non-fiction account of the men and women who work in the French oyster industry, The Oysters of Locmariaquer. Her vision stabilized about six months after she was stricken, allowing her to perceive dim, impressionistic glimpses of the world and return to her writing. Composing sentences by drawing giant Magic Marker letters on blank sheets of newsprint then transcribing these jottings with a large-type typewriter while peering through a lighted magnifying glass, she wrote a book about the fight to regain control of her life.

Eyes Etc.: A Memoir details how she meticulously arranges every pot, pan, and scrap of food in her kitchen to foster a reliance on memory, not sight, when she is cooking. Her meals are triumphs of culinary determination, but she solicits no sympathy and in fact discourages pampering. She is a strikingly handsome, green-eyed Connecticut Yankee with high, bold cheekbones and a thick mane of straw blond hair. Her literary and political roots extend deep into the New York of the 1930s—a world populated by Communists and revolutionaries. She was a Trotskyite, although she labored harder on essays for publications like The Partisan Review than on implementing social reforms in America. Her marriage to Warren is one of sweet collaboration wed to a propensity for ceaseless oratorical battle. They disagree on politics, people, literature, psychology, and economics. She is the liberal Eastern aristocrat; he is the clodhopper scholar with dung on his boots and poetry in his heart. For twenty-seven years they have had a sturdy, loving marriage. During the months when she was certain she would lose her vision, he read aloud to her almost every night from the works of the blind poet, Homer.

“My house in the North is really just a big hotel to me. A place I stay. The South will always be my home.”

“Pass me the chicken, please,” Clark said as Warren concluded his harangue on the vapidity of the political functionaries trying to deal with the energy crisis.

“Yes, darling, here it is.” He handed her the platter. The Warrens, Rosanna, and a woman friend sat around a large table in the upper portion of the house. This expansive living area is decorated with an old upright piano, two huge Jack Daniels decanters, a bas-relief map of southern Vermont constructed by Gabriel, and many pieces of well-worn, comfortable furniture. On one coffee table was an issue of The Atlantic Monthly containing a poem by Rosanna. On another was a copy of an academic journal featuring one of her father’s poems.

“Thanks, Red,” his wife said, taking a chicken breast from the plate.

“You all know they closed the gas station in Jamaica last week,” Warren groused. The village of Jamaica, a tiny gathering of proper white New England churches and lodges, is about ten miles down Bald Mountain Brook valley from the Warrens’ house.

“We’re just going to have to learn to live without cars,” Rosanna said. “I’m terribly worried about the mental health of the American people. They’re addicted to driving.”

“I’m worried about that, too,” Clark said.

“Well, I’m worried about their moral health,” Warren countered. He smiled. “I’ve been saying this for a long time, but I think the whole guts have gone out of the American state of mind. Americans now want it done for them. You can trace a lot of this back to that business of the New Deal. Now, I’m a New Dealer. But I don’t think you have to make it so easy. One time that old witch lady of the Roosevelt family told me all about it. What was her name?”

“Eleanor Roosevelt,” Clark offered, her voice rising slightly.

“No. Damn it. She was a witch, but she didn’t have any brains. I mean the bright one. Oh, you know – the one who lives in Washington.”

“Who are you talking about, Red?”

“Oh, the famous old witch. Alice Longworth. Yeah. I met her once. The only time I ever saw her, we spent an afternoon together talking about the Roosevelt administration. And she said that the one thing you have to remember about FDR, the one thing that everyone else overlooks, was that he was a cripple in a wheelchair and that he wanted to make all Americans the same way. He wanted everybody to have someone to push them around.” Taking a drink of wine, Warren smiled like a fox. Rosanna and Clark clucked audibly.

“Oh, come on Red,” Clark said. “I can’t believe you’re saying this.”

“Now, just a minute darling,” Warren pleaded. “She is a wicked old lady, but she is sharp as hell. As sharp as hell.”

“No. No. No. No.” Clark’s voice exploded each time she said the word.

“Darling, I’m not saying this,” Warren begged. “She said it.”

“I’m really ashamed of you, Red. To quote this sympathetically is preposterous.”

“Well, I’m quoting it humorously, darling. Can’t you see?”

“Oh, come on. It’s not funny at all.”

“It’s not only funny, it’s half true.”

“Stop.” Her eyes fixed him.

“I think it’s obvious that most Americans are now patients.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“There’s something very profound in the notion, darling.”

“I think we’d better stop this right now,” Clark said, pounding a glass down firmly on the table top. “Stop it before I really get hot.”

“Now, what are your politics, darling?” Warren asked, slipping in the dagger. His voice cracked mischievously. “I’ve forgotten what party you belonged to.”

“Oh, Jesus, honey. Will you lay off? You’re so obstreperous.”

“Well, I’m sure everything I say will be discarded.” His tone was at once plaintive and mocking. He smiled. Abruptly, Frodo began barking and howling wildly from beneath the table.

“Yes, Frodo, I agree with you,” Clark said, commiserating with the animal and rubbing its head. “Having to listen to him go on like that.”

Warren smiled grandly. “That Alice Longworth was a spunky damn dame.”

“Red.” Her voice buzzed.

Placing a hand on her father’s shoulder, Rosanna attempted to placate them both. “You two remind me of those Romanesque carvings in which you’ve got a little stone soul being torn apart by a devil and an angel.” The Warrens laughed, and Rosanna passed the bottle of wine to her father as an appeasement.

“Well, to say the least, the mental health of America is pretty bad,” said Clark, her face calming as she negotiated a return to the original topic of conversation. “There’s so much real craziness today. Bizarre murders. You know, in the past, a story like Jack the Ripper became folklore. And Bluebeard became legend. What was his real name?”

“Gilles de Rais,” Warren said.

“Thanks. But, ah, these things were so extraordinary when they happened back then. But now it’s so commonplace in America that we’re inured to it. Son of Sam. The Texas Tower murders. What’s really awful is that atrocities happen so often that we accept them as commonplace.”

“Yeah,” Warren concurred. “You just shrug your shoulders and ask, ‘What’s the next piece of news?’” Shoving a forkful of salad into his mouth, he chewed pensively then added, “Our civilization is spewing out more and more of its ordure as it goes along. It’s a great big machine, and it spews it out, and it’s human waste.”

In 1939, standing on the northern tip of Capri and looking out to sea toward Europe, Robert Penn Warren was feverish with the knowledge that the whole world would soon be at war. The Mediterranean island was fertile ground on which to consider a conflict that might destroy civilization. It had already been the site of barbarous decadence. Here, Tiberius, the brooding, vile-tempered Roman emperor, had staged the wild sexual dramas that preceded the decline of his empire. Gazing over the water, thinking of the coming conflagration, Warren felt helpless. Finally, he tossed a stone into the dark brine; it was all he could do. Years later, he wrote a poem about that night. While the range of Warren’s poetry is broad both in style and subject, “Tiberius on Capri” is emblematic. His poems almost always deal with history or nature and man’s place in them; they almost always incorporate a bloody incident and tie it to a metaphysical rumination. While “Tiberius on Capri” has no story line (many of Warren’s longer poems read like fiction; he in fact abandoned short-story-writing because the impulse conflicted with the composition of poetry), it is richly descriptive and binds the grim past of the island and the looming destruction of World War II to a philosophical consideration: what is a man to do in the face of a world in which he is helpless to change things? As Warren has grown as a poet, this confluence of guts and ideas in his work has occurred more and more.

During the past quarter-century, Warren has written a phenomenal amount of poetry, receiving more critical acclaim for his poems than for his novels. Recently he has concentrated most of his efforts on poetry because he feels he might not have enough time left to produce another novel. “My poetry allows me to live so intensely,” he said. “It’s an immediate transaction with the world around me.” Warren’s verse pullulates with striking images that can wrench a reader to attention and wonderment, and his best poems stew with sensuality. About dancing with a young woman he wrote:

Flesh, of a sudden, gone nameless in music, flesh

Of the dancer, under your hand, flowing to music, girl-

Flesh sliding, flesh flowing, sweeter than

Honey, slicker than Essolube, over

The music-swayed delicate trellis of bone

That is white in secret flesh darkness …

Yet as evocative as Warren’s descriptive touch can be he is at his weakest when trying to draw conclusions from the rich images. He slips occasionally into didacticism. This tendency toward heavy-handedness springs from his instincts as a novelist. Warren has pared much of the rhetoric from his poetry writing during the past twenty years – gaining, as a reward, an utter command of a hard, fecund Southern verse style. But there has been a cost. As he has stripped away this tendency in his versification, he has also pruned it from his novel writing, weakening his fiction. Reviewers have responded harshly to such recent novels as Flood, Meet Me in the Green Glen, and Warren’s 1977 book, A Place to Come To. While the latter novel strongly recalls the dazzling prose that makes All The King’s Men explode with stylistic pyrotechnics, it is spotty, depending on an intellectual framework where All The King’s Men is both cerebral and visceral. Still, as even one of the new novel’s harshest critics allowed: “His many admirers will find isolated passages and striking images scattered through the book that are the equal of anybody now writing in English.”

A Place to Come To chronicles the life of a displaced Southerner driven from his home by his mother’s hatred for the mean, ignorant, hookworm-ridden Yahoos of his native Alabama. The book could be interpreted as autobiographical. Since leaving a teaching position at Louisiana State in the 1930s, Warren has returned to the South only for short visits. But he contends that there is no trace of himself in the novel’s narrator, Jed Tewksbury. “He hated the South,” Warren said. “I love it. My house in the North is really just a big hotel to me. A place I stay. The South will always be my home.” Warren says he was forced from the region by economic necessity. “Shortly after I came back to the South,” he recalled, “I began teaching at Vanderbilt. I could have gone to California, but I didn’t want to. But after three years in Nashville, they let me go. I couldn’t get along with the department head.” After leaving Vanderbilt, Warren taught at LSU. “I loved Baton Rouge,” he said. “I had a nice place to live there, and I loved New Orleans. I used to go to a bar there where the bartender would set a bottle in front of me on the table and say, ‘Pour ‘til your satisfied.’ It was fifteen cents a drink. And they let me keep count of the tab. God that was living. You couldn’t find that in the North. But LSU wouldn’t give me a $200 raise when I thought I deserved it. So I went to Minnesota to teach.” In the years that followed, Warren often considered returning home. Shortly after he married Eleanor Clark, she suggested that they buy a farm in Tennessee so their children could learn about the South. “I went back,” Warren said, “and looked around, but it just wasn’t the same anymore. I couldn’t find anyone to talk to. Before, I could talk for hours with any dirt farmer sitting on a split rail fence. But the rural South, my South, is vanishing. Because it was such an impoverished place, it was particularly vulnerable to having the TV culture superimposed right on top of it. It’s not my South anymore.”

It has been more than forty years since Warren lived in the land of cotton, but the region still influences much of his poetry and all of his fiction. The power of Warren’s novels, however, has diminished in the decades since he left. It was his sure knowledge of Southern manners, his intimate acquaintance with the subtle nuances of life in Tennessee and Louisiana that fed his best works. All the King’s Men—the book that would have assured his place in literature had he never written another—is vivified by his knowledge of the region. During Warren’s last years in Louisiana, he witnessed the ascension of Huey Long to power. Long’s influence at LSU was enormous. The ROTC was his personal army; the football team was his band of gladiators; students with politically powerful parents easily found academic success. While teaching English at Baton Rouge, Warren was caught in the prickly thicket of turmoil spawned by Long. “But the thing you have to remember,” Warren said, “is that before Long, Louisiana was a worthless state. No government. No literacy. No hospitalization. No free roads. No schools. No nothing. It was rotten. Huey Long’s genius was that he saw this vacuum. Long got me thinking about doing the novel, but I wasn’t really interested in him. I was interested in the whole question of power in our age. The Mussolinis and Hitlers. The question of means and ends. I didn’t do five minutes of research on Long. I didn’t really give a damn about him. I was reading Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Williams James’ works on pragmatism, and Machiavelli. I was interested in how power corrupts absolutely. I saw that at LSU, and that gave the book a setting. But it was about Long in only superficial ways.”

The idea to write All the King’s Men came to Warren one humid afternoon as he sat on the front porch of a cottage rented by LSU graduate student Albert Erskine, later to become his editor. Rocking idly on the porch that day, Warren told Erskine he was going to write a play about the recently assassinated Long. He did not yet have a plot for the work, but he envisioned a verse drama with choruses of doctors, policemen, and politicians. The central theme: what good can be made from evil? Warren actually began writing the play in 1938 while sitting beneath an olive tree in the wheat field and vineyard country of Italy’s Umbria region. When he finished it, he put it away. He sensed something was horribly wrong with its construction.

“I’m obsessed with trying to make sense out of things by writing about them, because I regard writing as basically a means of self-knowledge and self-control. It’s a way of investigating my own nature. As long as I can write, I’ll be all right.”

Nearly three years later, during his tenure at the University of Minnesota, Warren removed the manuscript from a storage bin and reread it. “I remember distinctly the room where I was then living. I remember the desk. I had an apartment on Lake of the Isles. I almost remember the smells of that day. Strange. Anyway, I read the play again and was utterly dissatisfied with it. It was bad. The characters were all stunted.” After pondering the work for several hours, Warren began to be fascinated by an unnamed newspaper reporter who appeared in its last act for staging purposes. Warren thought: why not make him the narrator of a novel based on the play? Warren named the character Jack Burden and almost by accident created one of the most distinctive narrative voices in American fiction. In Burden, Warren not only had a perfect storyteller – a sardonic, cynical journalist – but a character whose deep emotional problems helped save the novel from becoming a political potboiler. In Burden, Warren embodied many of his theories about history and psychology. “Jack gave me someone I could toy with,” Warren recalled. “I could play with some of my notions about America with him – about the meaning of the West, for instance. At one point, Jacks runs away from it all in Louisiana – his girl and the Boss, Willie Stark, and the whole mess. He can’t stand it anymore. He goes to L.A. Now that’s just like an American. We go west to find the new Eden. We’ve been doing it ever since we came to this country. If you run west, the sheriff back home can’t catch up with you. But once you get out there, you find out you’re mortal. That’s the paradox of America. It’s the land of redemption, but it’s also a land in which human nature can’t be redeemed.”

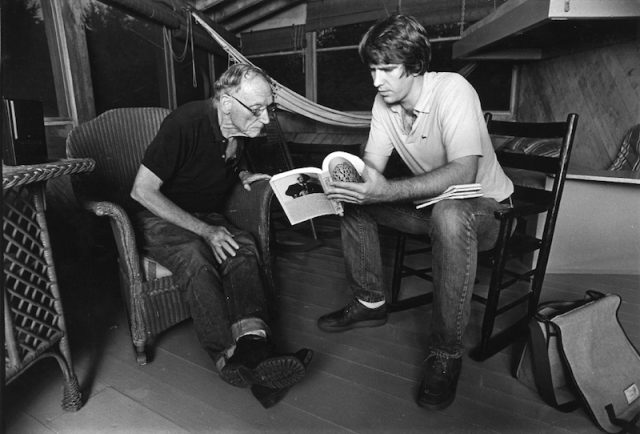

Late one afternoon as occasional gusts of wind blew out of the mountains bringing slight respite from the heat Warren sat on his front porch facing a visitor. The room was aglow in the roseate hues of fading day. Ensconced in a comfortable rocking chair, his eagle-beaked, strong-boned, ruddy old face twisted into a frown, he answered the visitor’s questions. Except for their voices, there was no sound.

“I’d be interested to know if you’re sad now that you’re old. Do you have regrets?”

“Ah … not really … I have my family and my work. But I don’t have many friends left. Most of them are dead.” With that, he wavered. “Katherine Anne Porter was a close friend of mine. What a beautiful woman she was … Is … There was never anything between us, romantically, but she was very dear to me.” His voice cracked. “I went to see her not too long ago in a nursing home. She’s dying now. On her deathbed. She’s eighty-six years old. Several strokes. It’s very painful … If only she could be herself again … Old actresses can turn on the beauty, you know … One minute they have it and … Well.”

“I know your life has been a success, but how have you endured the hard times?”

“Life isn’t an escalator,” he said gruffly. “But nothing horrible has happened. This sounds like a boast, but I’m obsessed, have been and am, with trying to make sense out of things by writing about them, because I regard writing as basically a means of self-knowledge and self-control. It’s a way of investigating my own nature. As long as I can write, I’ll be all right.”

“Now that you’re older, are the things you want out of life different?”

“Some of the things are obvious, I guess … I’m of a religious temperament, you see, but without religious conviction. I take Christianity as a myth. What it says bout the depths of human nature is largely true. But it’s not true in the sense of the sacrament being the transubstantiation of the real presence. That’s the argument between Catholics and Protestants, but I don’t even think it’s relevant. What I do think is relevant, and what I want to try to emulate now, is the example of Jesus. But any moral human being wants that. I want to give myself in sacrifice of some sort. To participate in the common body of human life … My poetry lets me do that, but it sounds so trite to say.”

“What do you care most about now?”

“The things I prize most about my life are having a happy marriage and having children I take great delight in. They aren’t servile. They’re goddamn independent. But they love us. And in this life of desperate uncertainties, that’s compensation.”

“There are other compensations, other rewards, aren’t there?”

“Ah, I don’t know. I’ll just read one sentence from this book.” He leaned over and picked up the manuscript of his forthcoming poetry collection, Life Is a Fable. After putting on a pair of half-rim glasses, he read: “This is an autobiography which represents a fusion of fiction and fact from varying degrees of perspective. As a question and answer, fiction may often be more deeply significant than fact. Indeed, it may be said that our lives are our supreme fiction.”

The place that Robert Penn Warren has come to in his life is nearly idyllic. There have, of course, been dark times, grim periods when he was haunted by demons. Shortly after he injured his eye as a young man, he feared that he would go blind and drank destructively, rushing off to hidden nooks where he could be alone with his trepidations. His first marriage ended in a painful divorce. During the last years of the entanglement, he could not write at all. For a decade, his life was littered with sheets of aborted verse, works that miscarried for reasons he still doesn’t understand. In 1971, he feared that he might be suffering from cancer. He lost weight, energy, and sleep. But a liver biopsy came back clean; later, a doctor would discover that he had been poisoned by a prescription for a minor ailment—athlete’s foot. Throughout his life, he has been consumed by feverish contemplations of evil, sin, and the at once bestial and angelic nature of America. Yet his days have breezed ahead pleasantly, determinedly.

In All the King’s Men, Warren describes the protagonist, Willie Stark, as a man born outside of luck, good or bad. He can spend his life discovering who he really is. Unlike most, he is not prey to fate. Warren, of course, has not lived unaffected by luck. In fact, fortune—in the form of a jagged stone arching over a summer lawn in a small Kentucky town—turned his hand to writing. His hopes of a naval career shattered, he decided to become a poet and spent most of his energy pursuing his ambition. He grew into maturity at a time when it was difficult to ignore how life in the modern world was progressing. He could no longer count on the verities of religion or political ideology or even science to give him his bearings. He sensed that what he could depend on were the constancies of nature, the anchors of memory and history, the safe harbor of family, and the difference he could make by shaping it all into poems and novels. His belief in the power of invention has sustained him.

One night at dinner, Warren was telling stories, intricate, riotous tales about old Indian fighters, murder trials, Southern ladies, and foreign journalists. He was in his element until the phone rang. Getting up, he answered it. His son, Gabriel – who had spent the last four years building an ocean-going schooner of his own design—was calling from Rhode Island, distraught, as only a 23-year-old can be, over a minor design flaw in the boat. He said he was going to sail it into the Atlantic the next morning and scuttle it at sea. For nearly fifteen minutes, Warren pleaded with him over the phone. Finally, his voice desperate, he shouted, “Son, come home.” Returning to the table, Warren sat quietly before his plate. His eyes were filled with tears.

“He’s a hard-headed boy,” he finally said.

“He’s like his father,” his wife said.

Sucking up his breath, shaking his head and clutching the table with both hands, Warren brought the matter to an end. “I can’t bear to talk about it.” Sighing, he added, “I know he’ll come home. I know things will be all right.”

Drawing another gulp of air, Warren began telling more stories. Stories about the Civil War, stories about the woods, stories about a woman who deceived her pastor into believing she was saved when, after someone dropped a match down her dress during services, she screamed, “The fire is in me.” Stories about time and nature. They were the stories he had lived by.

This story was first reprinted at the Daily Beast and is featured in the collection, A Man’s World.

[Photo Credit: Ed C. Thompson via Steve Oney]