Some don’t join the diaspora to the cities, to fill up the buildings and prowl the gray streets. Some decide to stay behind and work the land, and to work with the land—to live on it and play on it, dwarfed by its permanence, and secure in it. Because there is always this about the land, about prairie and pond and mountain: they never go away. Beneath a roof of sky, yesterday and tomorrow always have a great deal in common. And to live here, planted on the planet’s surface, so that you can sense the roll of the seasons and taste in them time’s renewal, is, inevitably, to feel some of that same permanence for yourself.

Perhaps this is why, one full year after Lane Frost died with a bull’s horn through his heart in the mud of a rodeo arena, his death is still so tangible and his absence so conspicuous—why his memory is not only unfaded, but growing more substantial: because the permanence has been rended against all reason and expectation, against all of the flows and currents.

Perhaps this is why his parents and widow and best friend still receive letters from people who have written songs about Lane Frost, and poems, and named children after him, and why strangers show up on their doorsteps to talk about him. Perhaps this is why his image now appears in a country music video alongside Martin Luther King and John Wayne. And why thousands of people will visit the memorial display at the Cheyenne Frontier Days this week, to touch the unimaginably soft leather glove, caked with resin, that Lane Frost wore on his last ride, and to caress the heavy blue leather chaps, a few yards from the dirt in which he died.

In the realest sense it was the worst wreck in the history of rodeo, the wreck from which the sport, it is now clear, will never recover.

The thing is, it was not a bad wreck, as wrecks go—and maybe that explains some of the lingering disbelief, the universal disquiet; anyone who’s seen any rodeo has seen a hundred worse. There will probably be a few worse today, in the oval arena beneath the sky so wide that the earth feels as if its been shoved right up into its brilliant blue belly. In fact, it was almost routine: he was tossed off, he got hit by a horn, he fell down, he got up again, and the bull turned away. By then, spectators were heading for the cotton-candy stand, applauding the ride. But then he fell again, face first, into the mud. The horn, or broken rib, had hit an artery, and within a few minutes, or seconds, he was dead.

And so, while it was not a bad wreck, in the realest sense it was the worst wreck in the history of rodeo, the wreck from which the sport, it is now clear, will never recover. Because it was the wreck that claimed Lane Frost.

To catalogue the details of his life in order to effectively convey what he meant, and still means, to the rodeo is like trying to explain the essence of the prairie by describing the color of its grass, and its dirt, and its livestock. In each case, to isolate the individual elements is to come up well short of an understanding of the phenomenon.

But it’s as good a starting point as any. First of all, in his twenty-five years, by all accounts Lane Frost lived his life above reproach. As a four-year-old he’d go out and rake the lawn without being asked, and as a twenty-three-year-old, as the world champion bullrider, he’d fix the fence. He’d help out in the stripping chute if a neighbor’s help had taken off. He’d pay the way for a paraplegic friend to fly to Reno for the finals, and tell no one. He never said no to a fan. He was a good husband. He resisted the lures of the buckle bunnies who linger late in a rodeo arena, looking to sidle up against the winners. If he’d been given an unfairly low score after a good ride, he’d keep his anger in, and wait until he was out of sight of the crowd to throw his hat. And if he and his wife, Kellie, were arguing and he was really angry, he’d flip the radio to country and western, because he knew she couldn’t stand it.

“He might not have worn a halo, but he was as close as I’d ever been to someone who did,” said Richard (Tuff) Hedeman, twice champion bullrider, Lane Frost’s closest friend and traveling partner for five years.

“He always cheered people up,” said Ty Murray, the best cowboy alive, a good friend. “You coulda drove all night, not had much sleep, not much to eat, see him and be in a good mood in five minutes. He was that way all the time. Around everybody.”

Besides all the other things he did, Lane Frost rode bulls, and this requires in a man’s makeup something exceptional. Lane’s dad, Clyde Frost, a man forged of something unyielding, spent a decade with the rodeo, riding bareback and saddle broncs, but he never put himself on the back of a Brahma bull.

The King—that’s what the other cowboys called Lane. It’s a label that, in American folklore, is not pitched around lightly.

Still, of the 1,050 cowboys entered in the current Frontier Days, 100 ride the bulls, and in the 750 rodeos sanctioned each year by the Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association, there is no shortage of either the fearless or the foolish, all anxious to sit astride an animal that weighs a ton, and that, for eight full seconds, knows nothing but rage.

In 1987, Lane Frost won the championship of bullriding, and won the biggest buckle you can win. Still, there’s a new buckle and a different champion crowned every year, almost thirty of them since the PRCA began awarding them. Yes, he’d won some money, more than most of the bullriders, more than $100,000 in 1987. But after expenses he probably grossed no more than $60,000.

Then, in 1988 Lane Frost did something no one had ever done, and his legend began to take strong root. He rode a bull named Red Rock, a bull that no cowboy had been able to stay on in 308 attempts. Lane Frost did. This was the rodeo equivalent of pulling the sword out of the stone. And in five subsequent rides, Frost stayed on the bull twice more, and Red Rock threw him three times.

The King—that’s what the other cowboys called Lane. It’s a label that, in American folklore, is not pitched around lightly. It’s an odd fit, the analogy, but it does fit. Like the other king, Lane was larger than life in life, and now he is much larger than life in death; his Graceland is the whole constellation of rodeo arenas that cover the western landscape.

But the title also does him a disservice, because in its allusion to the corpulent, sopping shell of a man who welded rock and roll to the American soul, it implies a mindless obeisance on the part of a herd of fanatics, worshipping an ideal instead of a person. Whereas Lane Frost more or less lived the life that embodied the ideal. The people who now remember Lane Frost remember him in his true scale and measure, which was only that of a man who lived his life very well and did his work with dedication. And in the land of livestock and grassland and corral and endless highway, that is more or less everything.

And that is why, for all of the temptation to see something profound in the death of a heroic American cowboy, we would do well not to try to analyze the essence of the legend, or take outsize meaning from his death. We would do better to simply note it, and not forget it.

The story of Lane Frost is a simple one. In a world where life is reduced to good and evil, Satan and the Lord, staying on the bull or falling off it, working the ranch or losing it, the death of a great cowboy is as profound as life can get.

That’s all it is, a cowboy’s death.

That’s all, and that’s everything.

“Mama, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” four men were singing in the middle of the Astrodome one night not long ago during the rodeo they call the Houston Fat Show—as if Willie and Waylon and Kris and Johnny really had any idea, as if four men who call themselves the Highwaymen but travel the highway in buses as luxurious as the Lusitania have the slightest idea about the modern cowboy.

In fact, the modern rodeo cowboy has the stablest of dreams: earn enough money to put down on his own piece of land, and buy a few head of cattle. En route, for all of the dirt and the muck, for all of the renegade pedigree, it is a clean and exhausting and fulfilling way of spending your time here.

“Where we grew up, cowboys were a way of life. They still are. We’re not making millions, but that’s not the point. If it wasn’t for rodeo, I wouldn’t have anything.”

“This is all we live for,” Tuff Hedeman was saying on the Astrodome floor, far removed from Willie and his friends. Hedeman has the bullrider’s slightly bowed walk, as if gravity is heavier where bullriders stride, and he has the same kick-ass eyes so many bullriders seem to wear. “Our heroes weren’t Roger Staubach and Joe Montana,” he said. “Where we grew up, cowboys were a way of life. They still are. We’re not making millions, but that’s not the point. If it wasn’t for rodeo, I wouldn’t have anything.”

For all of its violence, rodeo is a gentle sport, driven by the frontier impulse not to conquer the land or defeat its animals but to simply tame both, to effect a truce: spend eight seconds on an animal’s back and flee in safety. It’s a sensible kind of victory.

The danger is hardly a surprise. The bullrider is generally a small man, holding on to a rope wound as tightly as possible around the neck of a bull whose only instinct is to rid himself of the irritation on his back, and then, having done so, to search out the rider to give a payback for his audacity. There have been only eleven deaths in PRCA-sanctioned rodeos in the twenty-seven years of its existence, but few bullriders lack scars. Charlie Sampson, one of the best bullriders, has one ear, and the corners of his eyes are crowded with scars the shape of barbed wire. Some get hurt in the chute, which fits the bull like a coffin. Some insist on holding on to the rope even as they’re being thrown, and risk being whipped like a yo-yo right back to the horns.

“Rodeo isn’t a matter of will you get hurt, it’s a matter of when and how hard,” Hedeman said. “This is a game of wrecks.

“The scary part,” he said, “was that you’d never think it’d happen to Lane. He was a world champion. He was one of the best at what he did. You’d have thought he was the last guy it’d happen to.”

He’d had a rough two years after he won the big buckle, starting with the Olympics in Edmonton in the winter of 1988. There was a string of bad scores—the judging in bullriding is as subjective as in any sport, and if a judge thinks the bull isn’t bucking hard, which is a difficult thing to tell, he’ll lower the score. And Lane’s wrecks had started to pile up. In the Olympics he was knocked out for five minutes when his bull bucked him off in front of the chute, then turned around and walked over him—in the idiom, he got stepped on. And one month before his death, he lost his front teeth in Fort Worth when his face hit the back of the bull’s head.

“He was still winning,” Kellie Frost said one night in their home in Quanah, Texas. She was packing to move to Santa Fe. Lane’s National Finals Rodeo jerseys hung on the walls. There was a button that read, i’ve got frost fever. “But everything was not going like it usually did. He hadn’t won that much last year. He’d come home and say, ‘Maybe I need to find somethin’ else to do.’”

Lane rose, but then he motioned to the chute, where the other cowboys were sitting astride the fences. There was something wrong in the way he waved.

But things seemed to have turned around in Cheyenne. He’d had a good week, and in the final go-round on Sunday, when the horn sounded after eight seconds, and the scoreboard flashed an 86—out of 100, but a 90 is virtually unheard-of—he’d officially won more than $10,000. For the briefest of moments, between the time he let the bull buck him off and the time the bull caught him, the entire world of rodeo delighted in his return.

Ten seconds later, it had gone wrong. Everyone knew it, because when the ambulance pulled away from the grandstand, it was not going fast.

“It was a real common-lookin’ deal to me,” Ty Murray said. “It was stuff you see every day.”

The bull was nicknamed Bad to the Bone, but the name was just wishful thinking on its owner’s part; it was not a mean bull, not the kind that likes to maul the rider. There are bloodthirsty bulls, but most are not; even Red Rock is the kind of bull you can rub behind the ear when no one’s on his back.

At the end of the ride—a good ride, a great ride, he’s stayed up on the bull’s neck, in total control—he let himself free of the rope and slid down the hull’s back, and the bull flipped him off with a flick of its haunches. It was the picture-perfect getaway, textbook stuff. He sailed free, facing the sky, and then, in the air, he turned around like a cat so that he landed on all fours, four or five yards from the bull, in the dirt. But it had been raining all week, and the dirt was muddy, and he had trouble getting up—maybe just a microsecond lost, but a critical one, for the bull had circled around.

Now it dipped its head as Lane braced himself to rise, more as if to investigate the man, certainly not to gore him. In the tape, the bull looks bored, wearing that peculiarly vacuous expression that only cows and bulls can know. And then it looked as if it had decided not to bother and turned its head away. But its horns were huge, and remarkably pointed, and as it turned its head away, the right horn hit Lane on the back of the ribcage on the left side.

Then it walked away. Lane rose, but then he motioned to the chute, where the other cowboys were sitting astride the fences. There was something wrong in the way he waved. And then he fell in the mud, face down.

“I didn’t start worryin’ until I seen him lay there,” Ty Murray said. “I knew he wouldn’t lay there unless he was hurt real bad. There’s a million things goin’ through your mind.”

“I knew something was wrong,” Tuff Hedeman said. “First I thought he was knocked out. When we turned him over, he couldn’t see me. Someone said he’d stopped breathin’, and I knew it was going to be a long road.”

From the hospital, Tuff called Kellie at her hotel back in Texas, where she was supervising the stunts for a bullriding movie. It was the first Frontier Days she’d ever missed. Lane was due to come back and do some stunt work.

“Sometimes I feel like tearing out my hair,” Kellie Frost said. “Everything was so … good. It was the last thing from my mind, that something like that would happen, especially to someone as precious as he was. It makes me mad, because I think, ‘He never did anything wrong.’”

“You can’t hardly find better people than rodeo people,” said Lane’s mother, Elsie Frost. “It’s a special breed. And God let us have one of the best.”

The Frost home in southern Oklahoma features an array of dozens of buckles and saddles won in dozens of cities and towns and states, and many bear Clyde Frost’s name. In a room off the living room, saddles lounge everywhere you look, finely tooled leather saddles, things of great weight and heft.

The late Freckles Brown, a famed bullrider, was one of Clyde’s closest friends, which goes some of the way toward explaining why Clyde and Elsie Frost’s first boy was addicted to bulls. It was a deep pull. Elsie says Lane was five months old when, at a rodeo, he awoke from an infant’s sleep when it was time for the bullriding, most likely summoned by the sound of the bull bell. At the age of two, he was seen sleepwalking down a flight of stairs and out the front door, carrying a bull rope on his way to the barn. In the Frosts’ earlier home movies, a boy of four is seen astride a calf that is doing everything in its not inconsiderable power to buck the boy, who is bumping up and down with the ferocity of a jackhammer and holding on.

Later, swimming in the irrigation canal behind the family’s home in Utah, Lane jumped through the windshield of a submerged car that had been dumped in the water and cut himself under the arm so severely that one hundred stitches were required; on the way to the hospital he spoke once, to ask his mother if the cuts meant that he would never he able to ride bulls. When the family moved to Oklahoma, Lane was the only boy who rode rodeo at Atoka High School, but still, in his junior year, he won the national high school championship in Douglas, Wyoming.

“He was glorious when he was alive, and he’s glorious now that he’s dead. He give back to rodeo more than he got out.”

“If anything got in the way of a rodeo, like a ball game, the ball game would have to wait,” Clyde Frost said. “Her folks”—he nodded to his wife, sitting on the couch next to him—”was always buyin’ Lane little trucks and stuff, but they just sat there. He might use ‘em with other kids if they came over, but not for long. He’d always take them out to the corral, and they’d end up doin’ somethin’ out there.”

On a rainy morning, the Frosts were playing Lane’s videotape. Beneath the brim of his black hat, even on the television, Lane’s spirit was infectious and his demeanor disarmingly friendly. It was Tuff who said Lane could get a wall to talk. On the video, Lane has no difficulty filling sixty minutes talking bulls, but then, as Tuff also once said, Lane should have run for office, he liked to talk so much. Tuff and Tracie and Kellie lost count of the hours they spent waiting on Lane after the rodeos. He’d chat with every fawning fan.

The praise was less easy to find within the Frost home. “Clyde wouldn’t slap him on the back,” Elsie Frost said. “Even when Lane won, Clyde would try to find somethin’ wrong. Once Lane said to me, ‘No matter how good I do, I don’t do as good as Dad thinks I ought to.’”

Across the room, Clyde Frost does not blink. His is a good, weathered face, set in a permanent expression of no expression at all, the face of a man who expects neither too little nor too much from the lot he has been dealt. It was not Lane’s wealth of buckles and saddles and prize money of which Clyde was the proudest. It was the day the mail carrier remarked how stunned he was to see the world’s champion bullrider mending a fence, like a common man, a few days after he’d won the title.

“I don’t know how people are supposed to feel after a year,” Elsie Frost said. “I think we’re doing pretty good. Every thirtieth of the month is kind of a hard time. What amazes me is how especially nice everyone has been, and still are. You think they’d think, ‘They’re gettin’ over it by now, don’t need attention,’ but it seems like people are still givin’ it to us. A couple of cowboys came by the other day on their way to Arkansas. Things like that make you feel good.”

Outside, oak and hickory and pecan trees dotted the rolling grassland. “Lane done what not many people do,” Clyde Frost said in front of his home. Rain was patting the Bermuda grass, and it was the only sound for several miles. “I’d rather live half a life doin’ what I want to do than live to be a hundred and not.”

“Lane was a born-again Christian,” Elsie Frost said, “and this has saved some sinners. If this was going to happen, I’ve thought, let it happen at the rodeo, where it could make more of an impression than any other rodeo. I don’t think God takes lives—the Devil is the one who takes them.”

They held the funeral in Atoka, a few dozen miles down the highway from Cheyenne, because it was the closest church that could accommodate 1,200 people.

When they viewed his body, Tuff told Clyde and Elsie that that was exactly the way he’d looked when they’d turned him over.

All of them, Tuff and Kellie and Clyde and Elsie, like to take this wherever they go: He died doing what he wanted to do. He did not die in a head-on, on a back highway—that’s the greatest fear by far of all rodeo parents—or in a small plane nosing into a field at 3 a.m. He is not lingering in illness, or crippled, or handicapped. He died at the apex, after one of the best rides of his life, in the oldest rodeo.

“I don’t guess too many people can say that they lived their lives to the fullest, every day, and did what they wanted until the last day they did it,” a cowboy named Bobby Delvecchio said. “He was glorious when he was alive, and he’s glorious now that he’s dead. He give back to rodeo more than he got out.”

“There isn’t a minute goes by,” Tuff Hedeman says, “that I don’t think of it.”

One month after his death at the National Finals Rodeo in 1989, Tuff Hedeman told whomever asked that he wanted to win it all for Lane. Then he went out and did so, won the championship, and then stayed on his final bull for several extra seconds. He had both of their names inscribed on the buckle, And that evening, in tribute, the rodeo organizers turned Red Rock out into the arena alone. The bull looked lost, several people said. Tuff’s wife, Tracie, said it seemed as if he were looking for Lane.

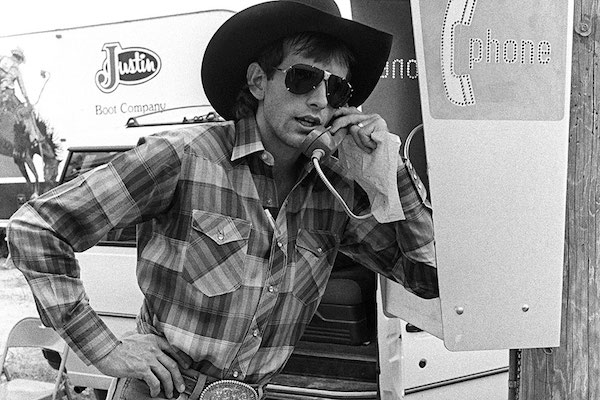

[Photo Credit: Lane Frost Challenge]