“Ladies and gentlemen, we regret there will be no national anthem tonight,” the public address system announced to 159 ladies and gentlemen and about 9,841 empty seats in Knoxville’s Billy Meyer (pronounced Billa Maahr) Stadium one night last August. “The record’s broke,” Harold Harris said in the wood-and-tin press shack atop the grandstands. Harris, the Knoxville Sentinel’s baseball writer, also served as official scorer, public-address-system announcer, and when the scoreboard boy was down getting cokes and hot dogs, as he often was, scoreboard operator. “It’s a bit much,” he said, “particularly when you have to spend so much time figuring a new way to say we lost.”

Harris and Alex Simpson, another Knoxville baseball writer, were filling me in on my first night with the Knoxville Smokies, a Cincinnati Reds farm club, who were in last place, 28½ games behind, in the six-team Class AA Southern League. The Smokies were playing a doubleheader with the Macon Peaches, who were in fifth place, 23½ games behind. One sportswriter, trying to work up a little interest among Knoxville’s fans, had billed the series “the battle for last place,” but nobody in Knoxville really thought the Smokies could escape the cellar and most of the Smokies agreed.

However, the first game that night was out of the ordinary because Lou Fitzgerald, the Smokies’ manager, had reversed his normal batting order in hopes of shaking the team out of a four-game losing streak. So as Harris announced the unusual lineup to the fans, Simpson gave me his own rundown on the Smokies.

“Batting first and pitching, Dan McGinn. (Great football player, McGinn. Nationally-ranked punter at Notre Dame in ’65, but he hasn’t shown much at baseball yet.) Batting second and catching, Frank Portera. (The second-string catcher, a nice eager kid just two months out of Mississippi State.) Batting third and playing center field, George Lattera. (The smallest guy on the team—only five nine. He doesn’t look much like a ballplayer, but he can catch the ball and he’s hit .287 since coming up from Sioux Falls last month.) Batting fourth and playing third base. Bernie Carbo. (The Reds were real high on Bernie—made him their number one draft choice in ’65. He’s got power, but he’s hopeless around the sack, just hasn’t got the reflexes for a third baseman. They’re thinking of switching him to the outfield.) Batting fifth and playing first base, Ron Cox. (Cox is the only boy on the club who looks like a ballplayer—notice how small all the others are. He’s big and strong—strong enough for the Cards to layout a $75,000 bonus for him a few years ago, but there’s less there than meets the eye.) Batting sixth and playing second base, Ike Futch. (Ike’s a good old Arkansas boy. Was with the Yankee organization for awhile and had a good crack at the majors until his legs went bad on him. Damn shame to see a boy like that with his legs gone bad.) Batting seventh and playing left field, Ed Moxey. (Ole Ed has been around awhile—in and out of the California, Carolina, and Texas leagues since ’61. He’s a good journeyman ballplayer but he ain’t going anywhere and Ed knows it.) Batting eighth and playing right field, Arleigh Burge. (Arleigh’s new to the club, came down from Pittsfield a couple of weeks ago, but right now he’s the best ballplayer they got and the only one hitting over .300.) Batting ninth and playing shortstop, Wayne Meadows. (A scrappy little hustler, but he hasn’t got the range for a shortstop. Players call him Taro because he waves at so many balls as they go past him into left field.)”

Fitzgerald’s lineup prompted a few chuckles in the stands, but he didn’t care. “What can I lose?” he’d told us before the game. “We’ve been going so bad anything’s worth a try. What’s more, I tried this once and it worked. I was managing the Tampa Tarpons then and we went fifty straight innings without a run. So I turned the batting order around and the boys were so surprised they beat Miami two to one.”

It didn’t work this time, though. In the first inning, Luther Quinn, the Peaches’ stocky third baseman, hammered one of McGinn’s fast balls over the left-field fence into the parking lot of the Standard Knitting Mills, near the illuminated billboard which read, “No Fit Like Healthknit—Underwear—Sportswear.”

The Smokies tied the game in their half of the inning on two errors and a scratch single by Bernie Carbo. But the Peaches scored again in the second after Moxey was slow getting to a fly ball looped down the line in left. It bounced by him all the way to the fence and by the time Moxey got it back to the infield the batter was on third.

Fitzgerald, who had managed Moxey on other teams and had been heard to call him a “lazy bastard,” was up on the dugout steps in a minute waving in Moxey, one of the club’s three Negroes, and motioning John Fenderson, another Negro outfielder, off the bench to take his place. Moxey froze, his long arms braced on his hips, staring unbelievingly into the dugout. Then he began trotting slowly across the field, muttering to himself. Fitzgerald, a big chaw of tobacco working in his left cheek, was waiting for him on the top step.

“We never win any ball games but we have some interesting discussions.”

The press shack hung out over the field near the Smokie dugout and Harris, Simpson, and I could hear most of what followed. Fitzgerald announced coldly that “that kind of loafing” would cost Moxey $25. Slamming his glove down on the dugout floor, the outfielder roared, “Why do you always get on me? What did I do?” Fitzgerald turned away, his cleats rasping on the concrete as he moved calmly along the top step, staring out at the field. But in the shadowed well of the dugout, before several startled pitchers and reserves, Moxey kept after him, bellowing, “You can’t fine me. I don’t belong to you. I belong to Houston. You can take your uniform and stuff it up…” At this Fitzgerald finally turned, the tobacco working faster now, and said that was okay by him and he’d send Moxey back to Houston which had “loaned” him to Knoxville earlier in the season. Moxey snatched his glove and stamped up the steps toward the dressing room.

The Smokies went on to lose the game, 6-4. They lost the second game too, 4-3.

After the second game, the Smokies’ dressing room was unusually quiet. The players stripped off their soaked uniforms (white with red “Smokies” across their chests, red numerals on their backs, red hat brims and socks) and hung them carefully on wire hangers in the green lockers (home uniforms are laundered only after each home stand). They hurried into the big communal shower, hunching their shoulders up under the erratic streams of lukewarm water. They dressed quietly, picking their slacks and California sports shirts from the jumble of gloves, spiked shoes, shower shoes, playing cards, liniments, and hair oils. Then they filed out the door past the Peanuts cartoon taped to the wall with the caption, “We never win any ball games but we have some interesting discussions.”

That evening, at the American Legion Club (one of three or four private clubs where the players gathered in a town which permits no public bars) the discussions were not about the club’s losing streak—now up to six games—but of Ed Moxey’s departure.

As an organist and drummer blared out rock ’n’ roll from behind the bar, pitcher Dan Neville swirled the beer in his glass. “We’re going to miss ole Mondo,” said Neville. “He may have goofed off a bit tonight but he was one of the last boys we had who could hit the ball out of the park and, believe me, with an offense like ours we could use a little of that.”

Nobody at the Legion Club mentioned that Moxey was the seventh Negro to leave the club during the season. Two of the others had been among the league’s leading hitters in 1966—Reggie Alvarez, who led the Smokies with 27 home runs, and Sam Thompson, who led the league in runs (114), hits (166), and stolen bases (60).

However, both got off to poor starts for the season and Don Zimmer, the former Dodger infielder who began the season as the Smokies’ manager, was not impressed. In June, Thompson got married. The day before the wedding he told General Manager Neal Bennett he wouldn’t be playing that afternoon because he had to attend the rehearsal. Bennett nodded, assuming he had checked with Zimmer. But when Thompson did not appear that day or the next Zimmer told him he was through. Two days later he was traded to Charlotte. A few weeks later, Alvarez made what Zimmer considered a “halfhearted” stab at a ball as it went past first base. The two had words in the dugout and Alvarez was released unconditionally.

The Smokies’ third Negro star in 1966 was Johnnie Lee Fenderson, the outfielder who had come off the bench that night to replace Moxey. In 1966, Fenderson spent little time on the bench as he led the league in batting with .324 and made the All-Star Team. But this season he was batting only .215 and the management seemed convinced he was loafing too. Earlier in the season, a beanball broke Fenderson’s “special prescription glasses” and Johnnie Lee said he would have to send to California to get new ones. When it took over a month to get them, and Fenderson refused to play without them, Zimmer accused him of malingering.

Johnnie Lee, a taciturn young man whose face wore a perpetual tight-lipped grimace which at times seemed to be a half-grin and at other times a half-frown, told me he wasn’t loafing. “I just never got my timing back after those beanings,” he said. But he made no bones of his suspicions that the management was racially prejudiced. “How else do you explain the Thompson, Alvarez, and Moxey things? There are white boys on this team who don’t hustle all the time, but nothing ever happens to them. When a black man doesn’t hustle just once, though, out he goes. Cincinnati told me I wasn’t hustling and they want to get rid of me. Well, far as I’m concerned, I can’t leave this club too soon. If they don’t want me I don’t want them.”

Fitzgerald, a native of Cleveland, Tennessee, who has managed many Negro players in his seventeen years as a minor-league manager, ridiculed the discrimination charge against a club like Cincinnati, which has such Negro stars as Vada Pinson, Lee May, and Leo Cardenas. However, there are pressures in the Southern League which do not apply in the majors. Integrated teams are still relatively new to some of the league’s cities—particularly Birmingham, Montgomery, and Macon. (The old Southern Association disbanded in 1961 because Birmingham and Shreveport wouldn’t accept Negro players.) Some league officials told me they believe integration is one reason for the sharp drop in league attendance—from 491,194 in 1960 to 362,000 in 1966.

Sam Smith, the rotund Georgian who is league president, said the reaction was particularly strong in cities where the teams went “a little overboard” and ended up with seven or eight Negroes in their starting lineups (both Charlotte and Macon have had that many from time to time). “I had some people, real old ball fans, tell me they were turning in their season tickets because they didn’t want to see the Black Barons play,” Mr. Smith said. “Let’s face it, there are folks down here who just don’t want their kids growing up to admire a Negro ballplayer even if he’s Willie Mays or Hank Aaron.”

A Nice Little Ball Park

By the time they arrived at the ball park the next evening the Smokies had shaken off the Moxey incident. It had rained that morning and the outfield was several shades lusher green, almost making you overlook the scuffed brown spots around third and short.

On nights like this, with the grass bathed in golden glow from the tall steel light stanchions, Billa Maahr was a nice little ball park. The roofed concrete grandstands seated 7,000 and two sets of gray bleachers along the foul lines provided 3,000 more seats, although they hadn’t been used for years except by the small boys the club paid to shag fly balls. It was a good-sized field—330 feet down the foul lines and 430 feet to straightaway center where the wooden fence was covered with bright-colored signs reading, “Rebel Yell, Bottled Exclusively for the Deep South,” “Bankin’ on the Smokies—Hamilton National Bank,” “M. F. Flenniken and Co.—Insure with Confidence—Our 62nd Year,” and “Supreme Lemonized Mayonnaise.”

As they spilled into the dugout that evening, the Smokies had resumed the gallows-humor banter which kept them loose in last place.

“Hey, who’s tonight’s starting loser?” shouted Steve Mingori as he slid onto the splintery bench in the dankness of the Smokie dugout. Mingori, a sad-eyed relief pitcher, was known to his teammates as “Fly” because one horrendous day in spring training a swarm of big black Florida flies followed him all over the field as he tried to eat an orange. (“I don’t mind for myself so much,” Mingori told me, “but I don’t like when they call my girlfriend Mrs. Fly.”)

“It’s the Cyclops’ turn,” answered Ron Cox looking up from the concrete steps where he had been oiling his big first baseman’s mitt. “I reckon we can count on him to make it seven straight.” On a team where everyone had a nickname, “the Cyclops” was John Noriega, a lanky (six-foot-four) former basketball star at Davis High in Kaysville, Utah, who was potentially the Smokies’ best pitcher but whose future was in some doubt because of an accident which had paralyzed his left eye and impaired its vision.

A serious young man determined to make the majors, Noriega was already out on the grass in front of the dugout warming up with Tom (“Tish”) Tischinski, the squat, first-string catcher who did not have Noriega’s ability but made up for it with a fierce competitive spirit. If the team had a leader it was Tish and he knew it. (“I like to have the people look up to me, even though I hit .180,” he said.)

But the other players who began straggling out onto the field showed little of Tish’s gusto or Noriega’s determination. Just to the left of the dugout, Burge, Meadows, Futch, and Fenderson began a desultory four-way catch, lofting the ball back and forth with big arm motions and catching it with equally sweeping motions of their gloves. Over by the field boxes, Mingori, McGinn, Lattera, and the team’s Cuban pitcher, Jose Lopez, were playing pepper. Grouped in a tight semicircle, they tossed the ball to Bernie Carbo about eight feet away against the boxes and he, swinging the bat softly, almost tentatively, plunked it back at their feet.

This left plenty of time to scan the stands for “beaver”—the team’s euphemism for buxom Southern belles. McGinn finally spotted one to his liking in the left field stands and he yelled over to Fitzgerald who had just entered the dugout, “Hey Fitz, let me coach third base the first inning; I got a little beaver work to do.” Beaver work entailed swiveling in the coaching box and fixing the target beaver with a long, soulful look. Having established eye contact, the coach would usually send a bat boy up to ask the beaver for a date. She rarely refused.

There was an unusually good crop of beaver in the stands that night because it was “Pony Night,” one of the promotions introduced to Knoxville by Joe Buzas, the club’s new owner and former New York Yankee shortstop, who had used them successfully to draw crowds for his two other minor-league teams—the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Red Sox of the Eastern League and the Oneonta (New York) Yankees of the New York-Pennsylvania League. When Buzas took over the Knoxville franchise in the fall of 1966 he said, “We’ll have to go in for lots of promotions, more than in Pittsfield. We’ll have to promote every day to lure fans back into the ball park.”

Already the Smokies’ had had a Scholarship Night on which the offer of a $500 scholarship had drawn 5,200 persons, a Merchants’ Night, at which 3,200 fans showed up for a chance at the TV set, bicycles, and radios provided by local merchants, and assorted other special “nights” on which ladies, children, or Little League ballplayers could get in for special prices.

Before the game, Buzas had confidently predicted that Pony Night—at which a brown pony as well as baseball gloves and bicycles would be given away to lucky ticket holders—would draw 5,000.

But at game time there were barely a thousand in the stands. Out at the concession stand near the front gate, where he and his wife were helping dish up hot dogs and cokes to save salaries, Buzas tried to be philosophic. Nodding at a red-and-white “Smokies Attendance Thermometer” on a pillar, which showed the 1966 attendance of 28,101, Buzas told me, “Well, we might just make that this year if we counted the batboys, the ball boys, the cops, and the ground crew.”

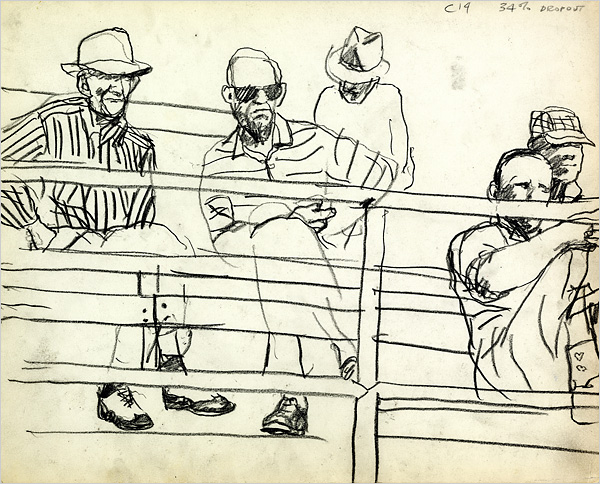

And you’d have to count the “regulars”—six or eight men in their fifties and sixties who have been associated with Knoxville baseball for most of their lives and attend almost all the Smokies’ home games. That night they were gathered in their usual spot—a row of seats in the reserved section directly behind home plate where they could banter with players on their way to the plate or with an umpire who wandered back to the screen. But when I joined them that night they were talking about the crowd.

“Promotion, hell, we used to draw a better crowd than this on an ordinary night coupla years ago,” grumbled Neal Ridley, the heavy-jowled president of the C & S Laundry who headed the syndicate of Knoxville businessmen which owned the Smokies until last year.

In 1956, Ridley; E. L. “Tip” Tipton, the dapper Budweiser distributor; Mike Gleason, the Schlitz distributor; City Councilman Roy Bass, and John Duncan, a lawyer who later became Mayor and is now the area’s Congressman, joined to bring the city into the Sally League after a year’s absence from organized baseball.

The syndicate had its days. The best were in 1959 when under Johnny Pesky, the former Red Sox star, the Smokies won the pennant and drew more than 100,000 fans. That was their last pennant, but even in the early ’sixties as a Detroit farm club, they were an interesting team. Most of the current Tiger stars played in Knoxville. But in recent years, as the club declined both on the field and at the gate, the syndicate lost too much money, and last year they closed shop.

The syndicate insisted it wished Joe Buzas weIl even though he is a Yankee from New Jersey. Yet at times some of the regulars seemed to get a sour pleasure that the Yankee wasn’t doing any better than they had.

“People are different down here,” drawled Ridley, surveying the empty stands. “They resent the hard sell Buzas has given them with all these Fancy Dan promotions. Advertising is a big part of your revenue. When I went after it I went to my friends and the people I did business with. I never had any trouble. Joe is a nice fella, but he came in here cold.”

TVA Changed All That

But the decline of baseball in Knoxville began long before Joe Buzas pulled into town. It probably began three decades ago when the “damn Yankee bureaucrats from Washington,” as they were once known here, came to town, bringing with them the Tennessee Valley Authority, which established its headquarters in Knoxville, then a slow-moving town on the slow-moving Tennessee River.

TVA brought not only a steady stream of electric power, flood control, navigation, and a substantial federal bureaucracy, but it pocked the virgin forests of the Great Smokies with a string of crystal lakes. These lakes, known as the Great Lakes of the South, have more miles of shoreline than their namesakes to the north and they were shimmering delights to the scrabble farmers and mill workers from the plains who had known only the sluggish Tennessee and its muddy tributaries. The sporting stores of Knoxville, which once used to sell chiefly bats and gloves, are now filled with outboard motors and water skis. Many a man who used to go out to see the Smokies at night can be found these summer evenings lolling by a beer cooler in the back of his boat on Norris Lake trolling for walleyes and bluegills.

The prosperity which TVA helped bring to Knoxville also spawned other ways of spending a summer evening: the drive-in theaters with huge screens set against the hazy background of the Smoky Mountains where couples snuggling in the bucket seats of sport cars watch Fastest Guitar Alive and Cheatin’ Heart; stock-car racing which, while not allowed in Knox County because of the noise, draws huge crowds at three dirt tracks set up just across the county line; bowling, at several new neon-and-chrome bowling palaces, whose business has been given a boost by the announcement that the 1970 American Bowling Congress tournament will be held in Knoxville; or, for that matter, just sitting at home, in an air-conditioned parlor watching The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

Channel 10 also brings the Atlanta Braves’ games to Knoxville ten times a summer. Along with the Games of the Week, this has undoubtedly undermined interest in the Smokies, “When you can watch Carl Yastrzemski on TV who wants to watch Arleigh Burge?” Tom Siler, the Sentinel’s sports editor told me. “Let’s face it, the fans are tuned to the majors these days, not the minors.”

“Whether they admit it or not, every guy here has his eyes on that pension. That’s what he really cares about and if he admits to himself he’ll never get it he’ll leave the game.”

Knoxville didn’t have to watch television to know what good sports are. After all, the folks on Gay Street would tell you, “We have the Vols.” Ever since General Bob Neyland took over the coaching job at the University of Tennessee three decades ago, the Vols have been one of America’s major football powers. Today they fill 54,000 seats at $6 apiece every time they play at home. “The Vols have spoiled folks here,” said Don Fillers, a florid-faced insurance man who is chairman of the Smokies’ advisory board. “They’re used to a winner in the fall and they don’t want to watch a loser in the summer.”

While the regulars were hashing things out behind the plate, the Smokies were getting one of their best-pitched games of the year from John Noriega, a four-hit shutout which earned Noriega and his wife dinner at Jim Bradley’s Steakhouse (Jim offered two steak dinners for every Smokie shutout or home run, but he didn’t give away much beef this year).

The next day was Friday and, as on every Friday since July, the Smokies had canceled their game at Billa Maahr so the Stadium could be turned over to George Cazaro’s wrestling matches. Joe Buzas had discovered he could make more money on the concessions at the wrestling matches than he could on admissions and concessions combined at the ball game, so the Smokies took their game out of town.

This time they were playing league-leading Birmingham at McMinn Central High School at Etowah, fifty miles south of Knoxville. The game was a benefit for Cathy Richardson, a McMinn cheerleader paralyzed from the waist down in a car crash.

The Smokies piled grumpily onto the big silver bus which they called “The Iron Lung” after its ancient, asthmatic air-conditioning system. I slumped down in the front right seat next to Dan McGinn, the ex-Notre Dame star who was having trouble making the adjustment from the adulation of the fans at South Bend to the apathy of the Southern League. “Coming along to hicksville, eh?” he said.

Across the aisle, Ken Widman, another young pitcher, was stretched out in the seat just behind the driver. Like McGinn, Widman had had his taste of glory—he won national press attention by striking out thirty-two batters in a three-hit, eighteen-inning game for Farmingdale Junior College in 1963. Their natural irreverence had drawn Widman and McGinn together until their teammates dubbed them “the Bobbsey twins.” In Knoxville they shared an apartment and in the bus they always took the two front seats, keeping the team laughing with a stream of ironic banter.

“Boy, Birmingham better not take us lightly,” McGinn crowed as the bus moved down the highway, “because we may not be able to hit but we can’t field either.”

“Yeh,” said Widman, the day’s starting pitcher, “we got an airtight infield. No air gets through. Of course, a ball now and then…”

When we rolled into McMinn High School we found ourselves in a country-fair atmosphere. The field had been fenced off with twine tied with little twists of orange and green cloth, behind which the local American Legion post had set up a hotdog stand. As the green wood stands filled with farmers in faded denim overalls and women with kerchiefs on their heads, the announcer for WCPH said, “This is McMinn County’s first professional baseball game. Athens might have had a team way back, but nobody can remember when. So we’re calling it the first.”

Widman, back at the Smokies bench after warming up, growled, “All we need is a greased pig.” But he went on to pitch one of his best games and when Bernie Carbo hit a three-run homer, the Smokies won 3-2.

Riding a two-game winning streak, the Smokies were noisy and boisterous as the Iron Lung creaked homeward. They zeroed in on Fitzgerald, who had spent most of the game behind the stands chatting with old friends up from his hometown, Cleveland, thirty-five miles to the south.

The Smokies, most of them young, reasonably well-educated (eleven had at least two years of college) men from the Northeast, East, or urban South, made no secret of their contempt for their slow-moving, tobacco-chewing manager, Fitzgerald, who started the season managing Cincinnati’s Triple A farm club at Buffalo, had feuded with the players there, and in late July had traded places with Zimmer, a hard-nosed, aggressive manager who in only two months had gained fierce loyalty from most of the younger Smokies. If the demotion from a Triple A to a Double A team bothered Fitzgerald (as it must have) he never let it show. On arriving in Knoxville, he told newsmen, “It’s good to get back in my country among folks who know me.”

He got along fine with the East Tennesseans who did know and like his easygoing manner, but the Smokies called him a hick behind his back. They laughed uncontrollably when he gave his favorite advice to wild young pitchers (“You’re in the woods hungry, with only one rock in your hands, and a rabbit comes by; if you miss the rabbit’s gone and you’re starving”) and they hooted at his grand passion—hillbilly music.

“Yeh, but ole Fitz can be pretty shrewd in his country way,” said Wayne Meadows. “He told me how one time he was managing down in Pensacola. They traveled in a four-car cavalcade and his was the only air-conditioned car. One day he had a young pitcher with him and he turned on the country music. The pitcher said ‘Turn that junk off.’ Fitz just stopped the car and told him he could hitch a ride with one of the other cars. The next day the pitcher asked for a ride with Fitz again. He said he’d made a mistake and he liked country music just fine.”

The mood in the Iron Lung was positively exuberant by the time it pulled into the parking lot outside Billa Maahr, but then a strained hush came over the team as they saw row after row of cars packing the usually vacant lot and heard the roar from the wrestling matches inside the Stadium.

“Okay, you cops,” McGinn shouted out the window. “Hold back those crowds. We’ve had a hard day and we don’t want to sign any autographs tonight.”

“You know, Dan,” Ken Widman chimed in. “I think you’re right. We ought to play our games between the halves of the wrestling matches.”

Inside, the 3,000 fans gathered around a ring set up at home plate were going wild as Corsica Joe picked up a huge belI and gave a good imitation of crushing Bull Montana’s head. “Kill the sonofabitch,” shouted a young woman with a baby in her arms.

Up in one of the runways I ran into Chris Maneff, known to his teammates as “Wetback,” a young pitcher from Los Angeles who gloried in his reputation as the kook of the team. (“I’m flaky,” he told me, “cut from the same mold as Joe Pepitone and Joe Namath.”) Maneff, whose Greek parents run a barbecue parlor in Los Angeles called “The Flying Saucer,” claims lineal descent from Alexander the Great. In the off-season he worked as an extra in the movies (his favorite role was as a Hun in Taras Bulba with Tony Curtis) and he affected the California style—tapered pants, wide belts, and Italian sport shirts. But he had a fierce pride in baseball as a way of life and a conviction that he was going to make it big (“I know I’m a major-league pitcher”).

The spectacle that night was just too much for him. “All these people look as though they’d been picked by central casting,” he sneered. “It’s really encouraging to see the folks down here know a great sport when they see one.”

Back in the dressing room, as the rest of the players stowed their gear in their lockers, Carl Barnes, the twenty-four-year-old infielder, was cleaning out his. The game at Etowah had been Carl’s last in professional ball. He was returning to his native North Carolina to teach civics and coach baseball and football at Granger High School in Kensington. A graduate of East Carolina College, Carl had played two years at Tampa and Peninsula before coming up to the Smokies halfway through the season and he hadn’t done badly—batting .270 in 150 at-bats.

“But I told myself at the beginning of the season I was either going to make it big this year or I was going to calI it quits,” he told me as we sat on the bench in front of his locker. “It seems to me you’re wasting your time if you don’t face facts after a certain point and realize whether you’re going to make it or not. I know now I’ll never make the majors. I could probably go on playing minor-league ball for a couple more years, but that’s not the kind of life I want.”

Eyes on the Pension

Most of the Smokies conceded that for them baseball was not a way of life but a way of earning a living. If they could make the majors and stay there for five years they qualified for the major leagues’ pension scheme—one of the most lucrative anywhere. But minor-league balI was anything but lucrative—most of the Smokies made from $700 to $900 a month for the five-month season—and even with the bonuses they got to sign it was not attractive money.

“Whether they admit it or not,” Tischinski told me, “every guy here has his eyes on that pension. That’s what he really cares about and if he admits to himself he’ll never get it he’ll leave the game.”

Joe Buzas told me that the Smokies and other minor-league players of today are “just a different breed of cat than when I was playing. When I broke in with Norfolk in 1941 I was the only guy on the team with a college education—they all called me ‘College Joe.’ For most of the other guys baseball was all they had. If they left the game they’d have to go to work in a factory. But half these guys here have got college educations and almost everyone’s got a high-school degree. They’re plenty of other things they can do. They’re just different players—not hungry, not breakin’ their necks out there.”

The next few days were bad ones for the Smokies. On Saturday they were shut out twice by Birmingham, 3-0 and 4-0, as their never-potent hitting attack fell away to virtually nothing. Finally on Sunday everything fell apart. The Smokies committed seven errors and lost 10-3.

Now a full thirty-three games behind, the Smokies were a carefree lot as they climbed into the Iron Lung at midnight Sunday for the last road trip of the season—to Montgomery and Macon. “What the hell,” Mingori said as I slid into the seat next to him, “We’re so far out of it now we might as well relax and enjoy the scenery.”

There would be plenty of scenery. The first leg to Montgomery was the team’s longest trip—347 miles—which at the Lung’s lumbering pace usually took seven and a half hours.

As “Bussie”—the young driver—finished wiping the window, Neville yelled, “Come on, Clyde Beatty, let’s finish up and get this circus on the road.”

“You guys sure have confidence in yourself,” Bussie said.

“Our confidence ran out the last day of spring training when they told us you were going to drive us,” Widman shot back.

Ten minutes onto the road, Neville dragged a stool out into the aisle and spreading a suitcase on their knees, he, Tish, and Noriega were off on their usual all-night hearts game (starting with a nickel or dime ante but frequently reaching pots of up to $50 before the ride was over). At the back of the bus, several seats had been removed to make way for nine army cots for the next day’s starters, but few players used them. “The goddam fumes are so bad back there,” Ron Cox said, “if we let the starting nine sleep back there we’d probably arrive with seven or eight asphyxiated stiffs!” Only Mike Oates, the eighteen-year-old fireballer who was scheduled to pitch the next day, and Ike Futch, the quiet second baseman who could sleep anywhere, were curled up on the cots. Most of the players propped themselves up in their seats, their long legs hanging over the top of the next seats, and tried to catch a few hours’ sleep as the Lung crept into the Tennessee night.

At 3 :00 A.M., Bussie pulled into a roadhouse at Valley Head, Alabama, and I joined the Smokies inside for a cup of coffee and a piece of soggy cake. Alongside the cake on the counter was a display of Confederate flags, records like The Coon Hunters, and books like The Story of Robert M. Shelton—Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America. Joe Earl, a shy, good-natured pitcher who was one of the two Negroes left on the team, edged nervously into the roadhouse, bought a cup of coffee, and left. Fenderson stayed on the bus, staring moodily out the window. When the rest of the team climbed back on the bus they joshed Earl and Fenderson a little. “Whatsamatter, nigger boys,” someone shouted, “doncha like our Alabama hospitality?” The Negroes joined in the laughter which they knew was well-meant, much as occasional remarks like, “All niggers to the back of the bus,” were meant only to break the tension on an interracial team traveling in the South.

The Negro players had no serious problems in the cities where the Smokies played although in Montgomery they were nervous about going downtown after dark and asked Mingori, whom they called “soul brother,” to bring them hamburgers. But the roadhouses could be dangerous. Fenderson told me of one evening in Bessemer, Georgia, when the Smokies went into a restaurant on the way back from a game in Birmingham.

“We had a Negro trainer then from up North and he just marched into that old roadhouse like he owned it,” Johnnie Lee recalled. “There was a couple of real white trash in there and they took exception to a Negro sharing their counter, so they told the trainer to move on out. I think he said somethin’ about ‘civil rights’ and they went for him. The rest of the team jumped in and before you knew it we had one hell of a hassle going. The guy who owned the restaurant, he went out and grabbed the gasoline pump and started spraying gasoline all over me and Thompson. One of those guys kept yellin’, ‘Put a match to the sonsabitches,’ but nobody tried nothin’ like that. Finally everybody just wore out and we got on the bus and drove away.”

The Lung rolled on through the night and about 6:30 A.M. as the first drifts of smoky sunlight replaced the neon road signs, a few of the players began untangling their legs from the cramped seats and moving about in the dusky aisle. Neville and Tischinski stacked their cards and moved up beside Widman and McGinn, just behind Bussie, as they began to pull through the deserted outskirts of Montgomery.

“Jesus, I’m hungry,” said Widman, “that roadhouse cake is enough to give you ringworm. I could realIy go for some of those fine old Alabama pigs ears, chittlins, and collard greens at that place across from the motel.”

“Oh Lordy,” said McGinn, “it’s good to be back in the Cradle of the Confederacy. I always did like the old Cradle.”

Just after seven, the Lung groaned up the last steep hill and pulled into the Albert Pick Motel in downtown Montgomery. The Smokies clambered down only to find that Neal Bennett had failed to make reservations for that night so they would have to wait until the guests had checked out of their rooms. They straggled into the coffee shop, paid $1.31 for juice, two eggs, and coffee, which with a quarter tip used up more than a third of their $4-a-day meal allowance. Then they drifted back to the lobby where they sprawled on the couches, reading Playboy or Sports Illustrated or trying to snatch a nap.

When the Smokies took the field against the Montgomery Rebels barely ten hours later they looked as though they could use some sleep. Things went wrong from the start. Mike Oates, who some baseball men insist can throw a ball faster than anybody since Bob Feller, didn’t get a batter out. He gave up a single, a walk, a hit batsman, a walk, a single, and another hit batsman before Fitzgerald took him out. The Smokies lost 9-2.

The next night the Smokies lost their fifth and sixth straight, 2-0 and 3-2. Fitzgerald, who had gradually relinquished his third-base coaching spot over the past few weeks, let Widman and McGinn take over the coaching (both scanning carefully for beaver), while he sat in the dugout spitting yellow tobacco juice and telling me stories.

Fitzgerald obviously had lost interest in the Smokies. He dwelt more and more often on his “good old friend,” Paul Richards, who he said wanted him back in the Atlanta Braves organization. In the dugout that night he took out a worn leather folder with “Aberdeen National Bank” engraved on the outside and showed me a wad of yellowing clippings. “I was the guy who straightened out Steve Barber and Bo Belinsky,” he said. He showed me a clipping in which Barber told a Baltimore reporter, “If old Fitz had that much confidence in me I felt like I must have some ability and from then on I was okay.”

Fitz told me he had never had a worse team than the Smokies. “There isn’t more than two or three boys on this team who got a chance at the majors—Noriega, and Carbo maybe if they can find some place where he can catch the ball.” He said Cincinnati was inviting seven players down for the Winter Instructional League in Florida, which showed at least some interest in them. Beside Carbo and Noriega, the group included Lattera, Portera, McGinn, Oates, and Mingori.

It rained the next day and it was still raining when the Smokies got out to the park at 6:00 P.M. The infield was covered with a big green tarpaulin and the players sat around in the stands for awhile, watching the rain make big puddles. Then most drifted down to the dressing room where Neville, Powell, and Tish played hearts, Noriega and Meadows played golf with a couple of brooms and two baseballs, Futch napped on the trainer’s table, and Widman paced up and down the room slapping his fists into his hand and muttering, “Call it, call it, let’s get this miserable season over.” Three hours and twenty minutes later the umpires called it and the Smokies climbed into the Lung and went back to the motel.

Ten days later the Smokies ended the season in last place 36½ games behind. They finished with a home attendance of 21,390—about 7,000 fewer than in 1966 (only 59 fans showed up for the August 29 game).

In September, Cincinnati traded John Fenderson to the Yankees for a young outfielder named Archie Moore. In October, Buzas announced he was severing ties with Cincinnati and moving to Savannah, Georgia, There is no professional baseball in Knoxville this summer.

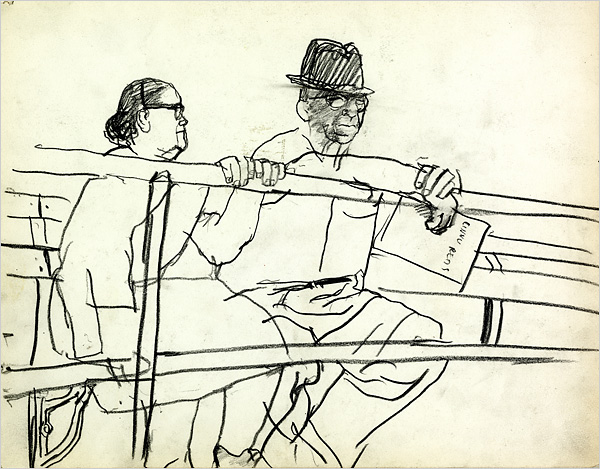

[Illustrations by Robert Weaver]