He was twenty when he began these voyagings, and he is supposed to have said then that this first trip around the league was like riding through a beautiful park and getting paid for it. Out of all those playgrounds, only Wrigley Field in Chicago is still used for baseball; everywhere else he is older than any piece of turf upon which he stands.

All has changed save him. No one else is still playing in the major leagues who was there when he arrived. Five managers are younger than he. In his first spring he saw the Braves in Boston; in his golden summer, he met them in Milwaukee; now, with the turning of his leaves, he finds them in Atlanta.

Before the New York Mets had ever played one game as a team, Willie Mays had already hit more home runs than all but six players then in the Hall of Fame. By now, he has stolen more bases than Rabbit Maranville, hit for more bases than either Ty Cobb or Babe Ruth, caught more fly balls than Tris Speaker, scored more runs than Honus Wagner and driven in more than Ted Williams.*

You have to come early to the Mets’ warm-ups to be certain of seeing Mays; more days than not, his most extensive exposure to the public gaze comes at batting practice with the other pinch hitters, those “extra men” left over after the starting lineup has been named. He takes his cuts two hours before game time with the Jim Beauchamps, the Dave Marshalls, the Ed Kranepools; he has hit more than four times as many home runs as all three of these playmates put together. It is very soon noticed that Willie Mays is the only one among them who runs to the box when his turn comes. “I’m gonna kill you cockseekers today,” he laughs. He fouls off two pitches then drives one to the grass just past the infield. “That’s a hit,” he cries. “You got to give me that.” They rule him out; “Cockseekers,” he grumbles and wanders away to pick up balls for Coach Eddie Yost to hit to the fielders.

Willie Mays had generally kept the mask of careless joy whenever the audience was larger than two dozen persons.

Here there bounds intact his image as eternal child. For here he takes his ease; he need fear no tests this night. But then there arrives an afternoon when he has been inscribed to start; and there falls upon him in the batting cage a desperation like the prisoner’s in his cell. The face cherished by his countrymen along with Ernie Banks’s as the last unaffectedly accommodating black one suddenly evokes some photograph from Attica, the nostrils flared, the eyes hot, the temper sour and nothing between him and despair except self-esteem.

Negroes who went young into the world put on and never quite took off a mask that carried them through the ordeal of inspection by great numbers of white people ; Louis Armstrong was over sixty before he gave way to those occasional dark flashes that suggested how ancient was his bitterness and how often renewed by the condescensions of the middle class. Willie Mays had generally kept the mask of careless joy whenever the audience was larger than two dozen persons; still a private reputation, of having grown sullen with the years, had followed him back to New York and his new teammates had been surprised to find him exerting himself to please them.

He had been especially cheerful after the first evening he had suited up with the team and the occasion had arisen for a pinch hitter and Manager Yogi Berra had sent in John Milner instead of the Willie Mays for whose sight the crowd was crying. Happiness, then, must be an arrival at some place when everything is no longer expected of you; and contentment some assurance that this could be a workday when nothing at all is asked of you except to sit and watch.

But this day he was down to play and the young Mets who had joked with a man-child a few hours before looked now upon a brooding god. His life has been one long responsibility, more often met than not, but always feared. For nearly eighteen years he had carried the Giants. His memory is scarred by the recollection of fainting spells in locker rooms; of the team collapsing around him in 1959 while he alone held the gate with a broken finger and hit five home runs in the last two dreadful weeks of the season; of the arrival at the third game of last year’s championship series so exhausted that, with no one out, a run already in and Tito Fuentes on second, he could only bunt and leave the decision up to Willie McCovey.

You remembered how often it had been said that Willie Mays knows more ways to beat you than anyone who ever played the game.

He does not want the load. He shouts for the bat boy to hurry and help him with his warm-up throws—“fuggin kids”—the playmate any other time, but now the imperial despot at bay.

Berra had him leading off. Mike Torrez, the Montreal pitcher, was not yet five years old the afternoon in 1951 when Willie Mays threw out Billy Cox from center field in the Polo Grounds, a ball traveling three hundred sixty feet to catch a fast man who had to run only ninety. Torrez paid his respects to this shrine by throwing two balls, the first wickedly close to the cap, the second evilly close to the chest. Willie Mays then watched a strike and another ball—he seemed as squat, as archaic, as immobile as some pre-Columbian figure of an athlete—then melted to protect himself with a foul tip and walked at last.

Ted Martinez came up to drive a long ball to right center and two outfielders turned and fled toward the wall with a gait that at once informed the ancient, glittering eyes of Willie Mays that men run like this when they have given up on the catch and hope only for a retrieval from the wall. Mays gunned around second and then, coming into third, quite suddenly slowed, became a runner on a frieze, and turned his head to watch the fielders. He was inducing the mental error; he had offered the illusion that he might be caught at home, which would give Ted Martinez time to get to third.

And only then did Willie Mays come down the line like thunder, ending in a heap at home, with the catcher sprawled in helpless intermingling with him and the relay throw bouncing through an unprotected plate and into the Montreal dugout. He was on his feet at once; his diversion had already allowed Martinez to run to third and he jumped up now to remind the umpire, in case he needed to, that when the ball goes into the dugout each runner is entitled to one more. base. Ted Martinez was waved home and those two runs were the unique possession of Willie Mays, who had hit nothing except one tipped foul.

“There is nothing in baseball that can get me excited anymore.”

You remembered how often it had been said that Willie Mays knows more ways to beat you than anyone who ever played the game. But that was no more than comment; and here was presence; and all historical memory was wiped out for this moment when Willie Mays had paused at third as if to array himself as proclamation of an army with banners. It was beyond any mere note of excitement; it was the tone of absolute authority. When we hear it in the blues, it comes less often from the Delta than from Kansas City. It grows in the bones of scuffling, isolated country childhoods. It is much more broadly country Southern than it is uniquely black. The only baseball player before Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays who played with that almost brutal abandon we call the black style was Enos Slaughter of the Cardinals, a native of Roxboro, North Carolina. You read the tone in Faulkner when Boon Clatterbuck stands beside the wagon “turbaned like a Paythan and taller than anyone there…. ‘Them that’s going,’ he said, ‘get in the goddam wagon. Them that ain’t get out of the goddam way.’” You can hear it in the old Venuti-Lang record of Farewell Blues, where there is a deal of slush and then a kind of stuttered note on the trombone and Jack Teagarden pushing everyone else aside. Boon Clatterbuck throwing his whiskey bottle away, Jack Teagarden almost clearing his throat, Willie Mays arraying himself for the charge—three pauses to assemble the irascible, occasionally even vicious dignity of the Southern country boy’s announcement that he is taking command of the city ones.

Those were all the runs the Mets would have that afternoon; and they would be just enough to win. Willie Mays did nothing else except catch two fly balls and thus twice routinely set a new record for total putouts by an outfielder in the whole twentieth century. In the locker room Yogi Berra did one of the minor managerial duties he was taught by Casey Stengel, in this case catering to the susceptibilities of the journalists for mythmaking. “I think Willie timed that throw,” he attested. “I’ve seen him do that before. He slows down and tries to hit the plate at the same time as the throw to make it hard on the catcher.” “Yogi lies a lot,” said Willie Mays affectionately. “You can’t time no throw like that.”

And he departed for Philadelphia and on Saturday drove in the first run with a double and scored the winning run after a walk, and the next day he beat the Phillies with a home run; the next Wednesday he scored the only run in a Met defeat; and Thursday he singled to break a tie with the Cubs after having played fourteen innings. He had returned to New York from San Francisco as half a pensioner; yet he had played six games and had produced or scored the winning run in five of them. In Chicago he hurt his finger, scrambling for some fragment of first base; he was healing and infrequently seen for the next two weeks. By June 8, he was healthy and marked down to start against the Reds. By then he had come to bat thirty-seven times as a Met and gotten on base nineteen of them; even so, as the shadow of responsibility came once more toward him, he again withdrew into that brooding silence from which no diplomatic jape of his teammates could coax him forth; isolated in the rubbing room, he left them to wait on the field until just before the game began.

Fuggin kids.

It began and would end most alarmingly. The Commissioner of Baseball had come to Shea Stadium in May to wonder aloud what sort of dynasty was being built here; but Bowie Kuhn is the stockholder type, which is to say that he fell off a horse when he was four years old, or suffered some such blow to his reason, and has since been conditioned to see in any transient rise of an issue the promise of unbreaking ascent. The Mets had since settled back to the scrabbling of the accustomed existence of teams able to trust their arms and their gloves more than their bats; and now they would win a close game and then they would lose another. And this day, in the first inning, the Reds fell for four runs on Tom Seaver, the league’s most effective pitcher last year. The Mets built a run in the first; Seaver righted himself thereafter but the game remained at four to one until the fifth when Mays singled off the pitcher’s shoulder and there followed two runs. Tony Perez hit a home run, and ‘the Mets came to the bottom of the ninth behind, five to three. Ed Kranepool pinch-hit a gentle single; and then Willie Mays was up. He swung so hard at the first pitch that his hat flew off; the respect of two successive balls was offered him and then, more viciously than before, he swung and shot a single like a 40mm. shell to left field. As often happens with him, you felt that the pitch had fooled him and that, in his passion, he had simply overpowered it. The note of authority had been struck; he was on first and Kranepool on second and there were no outs. The note vibrated in the air and there it died. Bud Harrelson bunted and Perez came down from first and seized the ball and threw out Kranepool at third. That killed it; the next two hitters expired on grounders and Mays was left at third.

He had had two hits for three official at-bats; yet afterward his solitary gloom was impenetrable. It had been an afternoon to stir uneasy prospects. There were so many small things: a lead runner thrown out at third base, the foundation stone of the pitching staff inexplicably shaky, such big-hitters as the roster holds failing—all signs that the Mets would never know the comfort of being enough ahead or the resignation of being enough behind. No, it would go on all summer, one more of those desperate adventures with an incomplete team that Willie Mays had known so often before with the Giants until the familiar horror of those final weeks whose reiterated torment had brought him, as long ago as 1965, to confess how permanently drained he was: “No. There is nothing in baseball that can get me excited anymore.” And yet there is not another Met who has known the ordeal of a close pennant race more than once in his career; and Willie Mays has been there eight times before. So, more and more, they would have to turn to him with too much of the load, and this would be another one of those cruel summers that, for just a little while, in the sun with the extra men, he had been able to entertain the illusion of escaping. Scowling, he strode through the children who had waited for him at the gate and alone he drove away, his face fixed in its contempt for destiny; everything that he had proved through all those years was worthless to appease him; nothing was ahead of him but the implacable duty of needing to prove everything all over again. Fuggin kids.

*These notations come from the Sporting News’ Baseball Record Book. They are not offered as argument for Mays’ superiority to anyone else but simply as a rough measure of his altitude in what is a range of mountaintops. Willie Mays may well be able to look at eye level at any other peak, except, of course, Babe Ruth. The best way to appreciate Ruth’s place beyond all comparison is to notice achievements of his that few of us would associate with him. The whole history of the game encompasses only thirty players who stole home plate more than eight times in their careers; and one of them was Babe Ruth. There are six pitchers in the Hall of Fame who were parsimonious enough to have yielded an average of less than two-and-a-half earned runs a game over their lifetimes; they are, in order of excellence: Ed Walsh, Mordecai Brown, Christy Mathewson, Rube Waddell, Walter Johnson, and Babe Ruth.

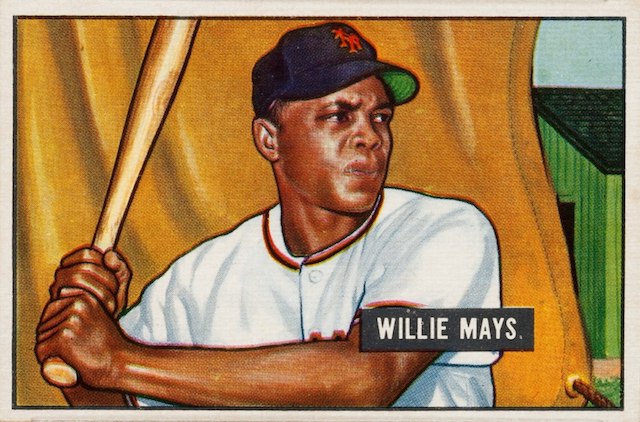

[Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons]