Ransom Stoddard, attorney at law, is doing his best to cover up, but the hell-forged maniac above him just keeps grunting and drooling and lashing him with a bullwhip. Stoddard is backed up as far as he can get against a stagecoach wheel, has his hands covering his face, but the whip is getting through. You can tell from the look on the Eastern dude’s face that he knows the whipping isn’t the worst of it. It’s the fact that this guy above him, this Liberty Valance feller, doesn’t look human. And the other guys in the gang aren’t exactly preppies themselves. Just behind Valance is Lee Van Cleef, with those little ferret’s eyes that are so narrow they look like cracks in old leather, and to the side, clapping his retarded hands together and giving this high-pitched, near-falsetto psycho laugh is Strother Martin. “Ah hah hah hah … you show him, Liberty … hah hah hah….” But as bad as those two are, the leader of the gang makes them look positively social. He’s got his feet spread and his head cocked to his shoulder, and this drooling, hanging lower lip that looks like it’s covered with swamp moss … the son of a bitch just hangs to his right shoulder, quivering, and spit flying with stone-cold hatred as he brings the whip down again.

Finally, Van Cleef and Martin realize Liberty is going too far. Hell, they just wanted to rob the stage. Van Cleef snakes forward and grabs Liberty by the arms.

“Come on, Liberty. The law might come.”

But Liberty is pulling out of Van Cleef’s grasp.

“You want to know about the law, dude?” he says to the terrified, dazed, and badly beaten Stoddard. “Well, let me show you law [whip] … Western law….”

Suddenly, without warning, the whole feeling of the scene changes. At just the right moment, the camera closes in on Liberty Valance and you feel his torture as well as Stoddard’s. He not only gives out pain — he is in constant, unrelenting pain. He’s in some kind of private, soul-killing hell.

But it’s only a second or two. Then, as before, the whip comes down.

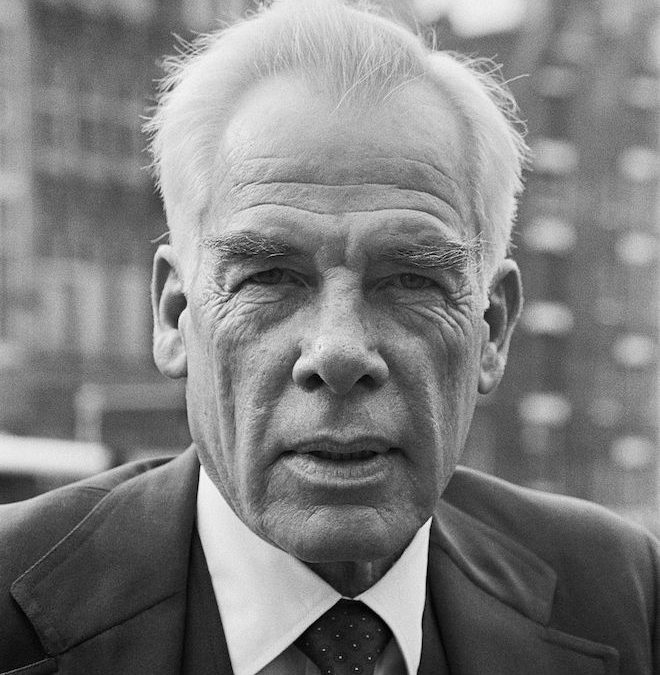

“Jesus,” I say, holding on to the edge of my seat as Lee Marvin clicks off the videotape of John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). “You looked like the devil himself in that scene, Marvin. How the hell did you pull that off?”

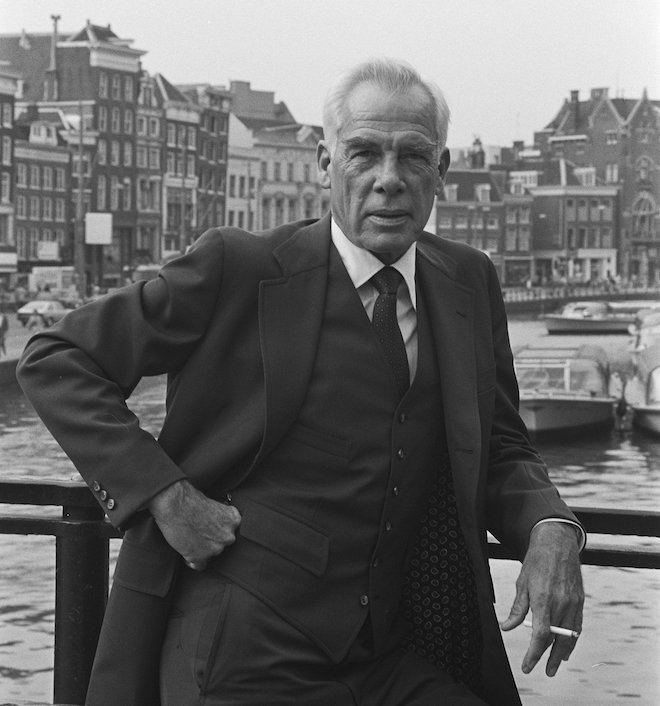

A few feet away in his comfortable, hacienda-style home in Tucson, Arizona, an urbane and congenial Lee Marvin reaches for the bottle of wine.

“I’ll answer that question, Ward,” he says, “right after we have this one final drink. If you know what I mean?”

“Now, Lee,” says Marvin’s wife, Pam. “Haven’t you had enough? You might not feel … well tomorrow.”

Lee Marvin cocks his snow-white head, lets the old lower lip start to hang down, turns slowly, slowly, and suddenly I am hit by the Fear. What if … he turns into Liberty Valance right here and how? Starts to horse-whip Pam? Brings out the guns on me?

“Payday. That’s it, Ward. Fuck all the other stuff. It’s important not to think too much about what you do.”

“We’re just having one … little glass of white wine, Pam.” Marvin says. “You understand?”

Pam smiles. She understands. She’s seen Lee when he wasn’t “well” before.

“I noticed something,” I say to Marvin, feeling a little like Ransom Stoddard, attorney at law. “In that scene we just watched, the sense of menace you created was linked to … how much faster you move than everybody else. The rest of them are standing still. But Liberty is always dipping his shoulder, whirling around. Was that your idea or John Ford’s?”

Marvin picks up his glass and takes a sip. He’s relaxed again, back in his own skin. “It’s one of the things I always do. I move faster onscreen. Creates a sense of danger … and ah…”

Marvin doesn’t finish his sentence. Though he’s perfectly capable of going on in greatly detailed style about what he does, he often just lets things hang.

“I mean,” Marvin says, looking at me through those glazed and slightly mad eyes, “you’re in there, then do it and get the hell out.”

“You mean,” I say, picking up our thirteenth bottle of wine, “that fast movement isn’t part of your subtle Stanislavskian approach to acting?”

“You ask me my motivation,” Marvin says, moving back into his tough-guy persona again. “I say Thursday.”

“Thursday?”

“Payday. That’s it, Ward. Fuck all the other stuff. It’s important not to think too much about what you do. Take Strasberg. I went to his joint once, back when I was first hanging out in New York, doing plays. I did a ten-minute scene in his class: the guy who had gangrene in his leg in The Snows of Kilimanjaro. After I did the scene, he starts in with, ‘Well, you were going for the pain in your leg, but I didn’t see it, so you didn’t put it over and thus the scene failed.’ I told him that he didn’t know anything about gangrene. When it’s in the terminal stage, there isn’t any pain. What I was going for was that the guy was trying to feel pain, because if he had any pain, it meant he wasn’t going to die. But he couldn’t feel a damned thing. I know about that shit from the Pacific. Strasberg was furious when I corrected him. He threw me out, so I said ‘fuck you’ and walked. He’s not my kind of guy at all. I didn’t dig it when he came in using his acting-school reputation to get the creamy acting jobs that some other old actor who’d paid his dues might have really needed. Nah, you can have him. He’s not in my outfit, pal.”

Marvin nods his head. The old sense of menace darkens his brow. To begin to understand Marvin, you have to understand “his outfit,” the one he signed on with when he was a kid during World War II and never really left — the Marines. But maybe you have to start somewhere else — with Lamont Waltman Marvin, Monty, his father, the Chief, the old man. Because when Marvin talks about the Marines, Monty, or the “screamers” — the directors he loved, like Lang and Ford — you realize they’re all part of the same outfit. The authority that he loves and hates. A harsh judge, one he might never please but has spent a lot of his life trying to. The old man, the Marines, and the director. And all of them are joined by one artifact. One image that provides a common thread — the gun.

Marvin clicks on the videotape again. Ransom Stoddard is hauled into town by John Wayne. He ends up working with Vera Miles in the kitchen of this Old West restaurant, where the steaks are all ten-pounders and the skillets three times the normal size. Marvin is delighted by the props.

“Ford,” he says reverentially. “Fucking Ford. You’ll never see skillets and steaks like that in anybody else’s picture. He’s like the Dickens. It’s all about bigger than life. That’s what the old guys understood about movies. If it’s not bigger than life, put it on television.

“We got along from the start. Maybe I knew how to deal with him. The first day of Liberty, I was hanging around waiting for Ford to come in. Everybody told me how tough he was and not to say anything or he’d single you out and get on you the whole shoot. But as he walked in, I got up and saluted him. There was a dead silence. And then I said, ‘Well, chief, when the admiral comes aboard, the first mate has to pipe him in.’ He never got on me after that. He was a great lover of the navy, and he liked me because of it. He called me Washington. Because my family is descended from George Washington’s brother, James. Which few people know or expect.”

Which is an understatement. The standard guess on Marvin might best be summed up by a writer friend of mine who said, “He looks like he came out of nowhere. He had no father, no mother, just spawned out there in some gulch and has spent his whole life hating the world that vomited him up.” Marvin would love that, for he’s worked hard to create his image. People don’t come over in bars with a glad hand and ruin his lunch. The reason is simple: they’re afraid if they do, he’ll kill them.

The facts are a bit more complex. Less legendary. Marvin grew up in New York during the Depression. The old man didn’t shrink heads or shuck shells for a living but was an ad executive. His mother wasn’t named Malvina or Bobbi Jean, and she didn’t belch him out in a truck stop and then leave him for the wolves. Her name was Courtney, and she was a fashion editor for magazines like Photoplay, Screenland, Silver Screen. So Marvin had the old showbiz glamour in his life from the start. Upon hearing this tale, most people are disappointed. They want Marvin to be as mean and as lonely and as trashy as the characters he portrays. But put aside the working-class sentimentality and you find that in spite of his blue blood and his wealthy parents, Marvin was the victim of another classic American tragedy — uptight WASP puritanism. “My father,” he told me in a bar in New York, “was the classic Puritan. Hold the emotions in check. Keep up appearances. Tight-assed. He had feelings, but he’d never show them to you. I remember once he told me about a bunch of horses he saw in World War I. They were twisted and dead from mustard gas. He cried talking about them. He had feelings. It took something like that to bring them out.” Marvin’s earliest memory of his father is so classic a case study that shrinks would stomp each other to get him on the couch.

“My father is shooting a gun. It’s a movie he took of himself with a Kodak B, which was a very good camera in the twenties — 16 mm. It was a film of him shooting near Randall’s Island, where they had a firing range. So he’s stripped down to the waist, with a .45 automatic — C98688 was the pistol number — that he got at Abercrombie and Fitch before he shipped out for World War I. And to watch him, the way he used to ride up, and in slow motion, when he fires, you see this ripple go up and down in his arm about four times, and then his shoulder moves like so, and then he starts to cock it, and up it comes like this, and it comes on in three waves, right on target, and this is on the speed targets. And he was nude from here up, with his hand on his waist. That’s one of the first memories I have. That, and him letting me play with his gun….”

When Marvin tells this story, he smiles a little, lets the jaw drop, and nods. He looks like the old cop on M Squad.

“Make of all that what you will,” he says.

Of course, he knows what you’ll make of it. He’s told it in a way that is so highly erotic there can be no mistaking his intentions. Yet, if you ask him if he ever learned anything from three years of therapy, he smiles and says, no, it was a long time ago and it wasn’t very useful.

Still, he will tell you candidly that he was his father’s son. He barely mentions his mother. It’s always his old man, the Chief. The Chief who went through World War I and then managed to get back into World War II.

“And it ruined him,” Marvin says. “He came home from that half dead, totally broken. I was in the Marines at the time, after my bouts with prep schools.”

“That was my relationship with my father. Through the gun. Always the gun. Does that help explain Liberty Valance? And why I loved Jack Ford?”

And, of course, there were quite a few of those. One was a Quaker school, whose name he can no longer recall, in upstate New York. He was already seething, filled up with the Chief. One day he and some of his roommates were cleaning their room and one of the guys threw the dustpan out into the hall. Lee asked him why he did that. The guy called Marvin a son of a bitch. Marvin threw him out the window.

“It was on a hill. So nothing got broken. The Quakers didn’t go for it much, though. They asked him to go home and commune with God and see the injustice of all this shit….”

After the Quaker school, Marvin served time at Admiral Farragut Naval Academy near Toms River, New Jersey, which he recalls as “eleven hundred dollars’ worth of uniforms in the Depression. God.”

But soon enough, Marvin followed his father’s footsteps. Right into the Marines. In a rare display of emotion, one that stunned Marvin when it happened and still stuns him now, the Chief, at age forty-seven, hitchhiked from his own army camp near Riverside down to San Diego, where his son was due to ship out with a raider group.

“The Marines put him up in the guard house,” Marvin says. “They understood what he was about because he had his World War I stripes on his arm. The next morning I’m up at five o’dock for breakfast, and my old man walks in.”

When Marvin tells this story, he gets quiet, and you can see the way it must have been. That act forever sealed his feeling for the Chief, bound it up with the war, with violence, with the gun.

“He gave me his .45 and said, ‘Here, kid, and don’t lose it in a crap game.’ I carried it with me everywhere, with one in the chamber and seven in back of the clip, until one night, these Wrapees were standing there right at face level. I don’t even remember unhooking the pistol, taking the safety off — there’s my hand flying back. Didn’t even hear it go off. And then to see this Jap just disappear.”

Wrapees was the term marines used for the Japanese because they had wrapping round their legs. In the morning, Marvin found the Wrapee he had shot with the Chief’s pistol.

“I had got him one inch from the tit, straight into the heart. I rolled him over to see where it came out, and there was no big hole in the back. There were a lot of little pieces, pieces of lead and stuff. It was copper jack, had broken up as it hit those bones. And more than anything, I wanted a souvenir for my father, so I rolled him back, and he had gold teeth. I took out my knife, my Ka-Bar, and knocked his teeth out, but they fell into his throat. Meanwhile, rigor mortis had set in, so he was stiff, and I couldn’t get ’em out. They said, ‘Come on, Captain, let’s go.’ My nickname was Captain, though I was a private, first class. So I had to move out. But I spotted the body and I came back, but some son of a bitch had cut his throat and stolen the teeth. I think about it now. The way my old man came home a complete wreck from the war. He was never the same after that. I had wanted to give him something, something to make him proud. Gold teeth. Those teeth would have sent him around the bend forever. I tell you this story to show you how impossibly young I was.”

It’s so quiet that all you can hear is the click of the ice-cube machine in the background.

“That was my relationship with my father. Through the gun. Always the gun. Does that help explain Liberty Valance? And why I loved Jack Ford?”

Of course it does. It helps. The rage that Marvin has embodied, a man on the edge of eruption, is always a badly wounded man. The Chief wounded him, and after the Chief was through, the war added its own licks.

“I was a point man, like in The Big Red One,” Marvin says. “It was at the Battle of Saipan. Me and another guy, Mike, were walking point. Now, a lot of people think that’s the most dangerous position, but I’ve done a lot of thinking about it, and I realized I walked through a lot of the enemy that way. They don’t want him and me. They want the whole platoon. That’s what happened when we finally got hit. They let us get ahead of the outfit, then the rest of the guys came in. Only then did they shoot Mike and me. They got him first. I watched him drop. Then they shot me, right in the ass. They finished off the whole company in fifteen minutes. I ended up getting carried out of there, and when I came out of the morphine haze, I was in this cream-colored room, and outside the porthole I could her ‘Moonlight Serenade.’.…A hospital troop ship. I felt crazy, like a coward. Because I didn’t go running out there to get the enemy and die like a lot of my buddies. You know the old saying? They gave him a gun, and he never put it down? Well, that’s true of me. Because there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think of that fire fight. Not all day, but every day of my life since.”

“How does it connect to the acting?”

Marvin smiles.

“I’ll tell you how. It was the Marines who taught me how to act. After that, pretending to be rough wasn’t so hard.”

Marvin has been aging well. Unlike the characters he plays, men who came from nowhere and, as he himself puts it, “go home to nobody.” Lee Marvin has survived his own considerable boozing, his infamous palimony case, and the bad memories of both the Chief and the war.

At his Tucson hacienda he is a gracious host and a good neighbor. The kid from next door drops by and Marvin talks to him about the stunts in his latest film, Death Hunt. Just like plain folks. Later in the afternoon, Pam’s son, Rod, his Japanese-black wife, Hideko, and their infant son, Morgan, visit. Marvin kisses the child and plays granddaddy.

Eventually the neighbors themselves make an appearance, everyone acting like Lee is a kindly white-haired retiree rather than an international movie star. Normality, domesticity, ease, in the blazing Arizona desert. It is his greatest performance to date. But late at night, when the wine eases him back into the chair, Marvin gets the haunted look we have loved and recognized as our own American terror since we first saw it on the screen in You’re in the Navy Now in 1951. The fear of … Dad, of the war … yes, that … but something else … the fear that life is nor being lived right here now. The fear that somewhere else it’s really happening; somewhere just outside the confines of your own house, your own scene, your own brain.

“Ask me if I’ve had a midlife crisis, Ward,” Marvin says.

“Have your”’

“No. Because I’ve always felt that way. Had to get to the next thing … had to find it….They say that hits you when you’re forty, but I can’t remember feeling any other way. Ever. Some of it you can trace back to the war, but I don’t get too Freudian about it; it’s just the way we are … You saw me today with the family. How did I do?”

“Oscar time.”

“You saw that, then? I was detached. I wasn’t really there. I was out, maybe in the Great Barrier Reef catching black marlin. Do you fish? No, you play basketball. But maybe it’s the same thing: The moment when you push through the wall.

“It’s like Jung in a way. I’ll tell you, I used to deep-sea dive, but I felt like an interloper. It wasn’t my world. I didn’t want to be spying on them. So after a couple of years I gave it up. But what interested me more was the unknown. You drop the line just below the surface, see, and just a few feet below there is something strange that will hit it … like dropping into a dream….Meanwhile, you’re on the deck with everybody else, and nobody talks. It’s the unwritten law. Nobody talks. Everybody is in his own dream … and then it hits … you see? Then everybody is in there working. You understand? No. Let me show you some films.” Pam’s daughter, Kerry, comes in. She’s a freshman at college.

“Boooooooring,” she says. “You aren’t going to bore everyone with those marlin films again?”

I look over at Marvin, who gives her a slow study. Then he smiles and sounds defensive.

“Hey, they aren’t that boring. I mean, the guy has to see it. Ah, what the hell.”

A few minutes later, all the lights are out, and Marvin is watching himself, with white stubble of beard, being described by two Aussie newsmen, officious types who mumble things like, “To Lee Marvin, the mystery of the Barrier Reef is a challenge … man against fish….”

Then they are interviewing him, and Marvin is making some heavy pronouncement like, “It’s me versus the fish. One of us has to die.”

“Jesus,” Pam says. “That’s awful, honey.”

Pam’s daughter goes into hysterics.

“It’s soooo baaaad,” she says. “It’s so baaad.”

“Shut the hell up,” Lee Marvin says. “I know it’s bad.”

Then he looks over at me.

“This is bullshit,” he says. “It wasn’t my idea, really. My captain on the boat, Brazakka, he wanted me to do this Hemingway bit, with the white stubble, and he wanted the hero angle. It’s not what fishing is really about at all. I don’t know why I let them film it, fucking up the thing I loved.”

Remember Marvin’s father. Throughout all the stories of loss and pain with the Chief, there was barely a trace of emotion. Like his old man, he keeps it reined in, but when talking about fishing, a true regret seeps out. Betraya l… you can hear i t… betraying the thing he loves for a cheap bit of film publicity. Yet there is something noble and even beautiful in Marvin’s regret. At least he know what’s been lost.

“Can’t we turn this thing off?” Pam’s daughter asks.

But Marvin puts his hand on her leg. He is straining toward the screen. It’s almost as though he wants to dive into it.

“This is it,” he says. “Wait….”

Suddenly a huge, graceful black marlin leaps out of the water, sending a shower of water ten feet high. It is a marvelous moment, and you can almost see Marvin’s mood change. He relaxes.

“It’s there,” he says, reaching for the wine bottle. “I felt a little of it then,” I say.

“No,” Marvin says. “You can’t … you can’t … unless….”

He can barely get the words out. Everyone is sitting stock still. He seems possessed.

“Through the other side,” Marvin says as the film runs out.

First light in the desert. The sound of birds, quail, even doe, make a wild grid of noise. It’s like sleeping in an aviary. I turn over, look at the clock. It’s six thirty … good, another couple of hours sleep before I trudge from Marvin’s guest house up to the main place for an afternoon session. I fall back into a dream and then suddenly there is a tapping on the window just above my bed. I pull back the curtain. It’s the original dog-assed heavy himself, smiling at me like Kid Shelleen in Cat Ballou.

“Get up, Ward. You’ve got to see the desert now.”

“Yeah, man. That’s a good idea,” I say. “I don’t want to oversleep. Christ, we’ve been zonked out for … like, two and a half hours. We could get weak … morally slack….Come on, man…”

But Marvin is holding up coffee.

“This will get you going. Hell, I’ve been up since five-thirty.”

“Jesus.”

I’m out of bed, Marvin coming in through the door now.

“Wait till you see it out there. It’s what we were talking about last night. Through the wall, oh, yeah.…”

Outside, sitting by his pool, we look out on the desert. It’s everything he said it is. And Marvin never tires of looking at it or talking about it. When he does, there is a gentleness in his voice, a reflective and lovely quality that no movie he has been in has ever captured.

“Those are saguaro cactuses … the big ones … birds make holes in them and build their nests inside.”

“And those?”

Marvin hops over the edge of his retaining wall, which he built. “Well, this shorter cactus, with the golden tip, that’s a barrel cactus. And this is an ocotillo, it’s tall and fingery, see, with one red flower at the top. It’s perfect….”

“How about the animals? I heard what sounded like werewolves out there last night.”

“Coyotes. But don’t worry, they don’t come down on people, though they will eat a dog now and then. But there’s also cottontail rabbit and jack rabbit and the Gambel’s quail. There’s one over there….”

I look up and see a quail hustling along the road.

“The roadrunner?” I say, recognizing nature by a cartoon.

“Remember, I didn’t make it until I was older, in my thirties. Up till then I was just a dog-assed heavy, one of the posse. My best friends were always stunt guys and extras. I’ve always seen myself as one of the masses. Besides, a lot of actors are just boring and pompous as hell.”

Marvin takes off his T-shirt and dives into his swimming pool. I dive in with him and swim to the bottom. The floor is inlaid with beautiful Mexican tile. Marvin himself cut the tiles. He likes when the sun glances off it from the top, because it looks like the black marlin.

When we come up, Marvin climbs out of the pool. His flesh is sagging a bit, but he is still trim and looks lean, sinewy and tough.

“Is it good to be here instead of in Hollywood?”

“Yeah,” Marvin says. “Now it is, but there’s a time when you have to be out there if you want to be in the business. Everybody puts it down, but it is what it is. There’s no other place like it. You meet everybody and you have a good time.”

“What other actors did you become friends with?”

“Not many. You don’t make friends with the guys who are above you too much. Remember, I didn’t make it until I was older, in my thirties. Up till then I was just a dog-assed heavy, one of the posse. My best friends were always stunt guys and extras. I’ve always seen myself as one of the masses. Besides, a lot of actors are just boring and pompous as hell.”

“I’ve heard you put a few of them on.”

“Well, yeah,” Marvin says, his head cocked reflectively. When his head cocks, you can be sure he’s going to let down the guard a bit, relax and tell a good tale.

“Like Rod Steiger. Now with Rod, you can’t help but put him on, You tell yourself, ‘Hey, this time ’round I won’t do it,’ but you can’t help it. Like it was ’65 when I was nominated for Cat Ballou, so I wasn’t even going to go because I didn’t think I had much of a chance to win. Steiger was nominated, and Richard Burton, and a lot of people in bigger movies. But I had won the British Award, Best Foreign Actor, so I went. Anyway, I get there early and—if you’re nominated, they ask you to sit on the aisles. So I walk in and there’s Rod, sitting and fidgeting on the aisle. So, like I say, I can’t resist it. I go up behind him and I say, “Hey, Rod, I see you’re sitting on the aisle,’ and he turns around real quick-like and his eyes are darting and he’s dry-mouthed and he says, ‘Yeah, so what, Lee?” and I smile real nice.”

At this point Marvin gives his Liberty Valance smile, the kind that makes you wish you could disintegrate in front of him.

“So I say, ‘Well, just this, Rod. If they call your name, and you get out of that chair, I’m going to break both your legs. You got that?’ And of course, Rod, being Rod, goes for it a hundred percent; his mouth drops open and he says, ‘What?’ So I just patted him kind-like on the shoulder and sat down. Every once in a while during the ceremony I’d look over at him and make a fist. You should have seen him. The guy was sweating. He was a wreck. I loved it. Loved it. Especially when I win. So I get up and do my acceptance speech, rah rah rah … and then we have the press taking pictures, and so a little later I’m in my limo and we’re heading for the Beverly Hills Hotel for the big party, and we pull up to a light, and there, next to me, is Rod.”

Marvin is totally into it now. He gives the greatest Lee Marvin big-teethed, killer-sadistic, gonna-eat-you-baby smile.

“He’s sitting in the back seat, and I swear, he looks like he’s crying. So I asked the driver to honk the horn, which he does, and Rod looks over. I held up the Oscar, and gave him a great big smile.” You can almost feel old Rod wasting away.

Marvin sits down in his chair and sighs. He’s settling back into his fifty-seven-year-old body. But while he was up there riffing about Steiger, he looked like he did in the Big Heat. Young and lean and mean as hell.

“Those were your drinking days, I take it.”

“Yeah, Marvin says. “But I was never a world-class drinker. I tried, but I just couldn’t keep up. Now the really great drinkers, well, let’s see, Robert Newton … old Long John Silver himself … Jesus, he could drink … and, of late, the best contemporary drinker is Oliver Reed. Ollie is unbelievable. Let me tell you. We did a movie down in Durango — Great Scout and Cat House Thursday. So I get on the plane with Ollie and he’s impeccably dressed and quite British, and we’re flying down there, and I order a vodka martini, which was what I drank in those days, and which nearly did me in. And Ollie doesn’t order anything. And I thought, ‘This isn’t the Oliver Reed I’ve heard about.’ So we get off the plane and go into Durango. And I stop of in the bar to talk to the director. Well, Ollie comes in with me, and, just to feel him out, to be sure I’ve got the right guy, I order a double vodka martini. And Ollie says, ‘Oh, I see, well, let me have two double vodka martinis.’ So I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll have two too.’ The director left then; he could see the impending catastrophe. So Ollie says, ‘Christ, thank God we’re off that bloody plane. I never drink on an aircraft.’ And then we started in….Jesus, this guy could drink. So after about an hour, we’re really getting down into it, and I notice we’re getting a bit loud. And there are these three or four very mean Mexicans sitting next to us. They have the serapes on, but I know they’re packing iron, and they start insulting us. You can hear ‘Gringos … fucking gringos.’ So finally Ollie gets this mean look in his eyes, and I say, ‘Now, Ollie, just look at me, just look at me, don’t look over there,’ and he says, ‘Fuck it, they can’t talk about me that way.’ He gets up and goes over to their table and introduces himself, and he says, ‘Hello, I’m Oliver Reed. Nice to meet you. I’ve heard the kind things you were saying about us. I just want you to know that I am not a goddamned gringo. I’m not North American. I am British. You understand? British. And I want you to understand one more thing as well. We sank your fucking Armada.’ With that he sits down. Now these guys are going crazy. Jabbering away. And I tell Ollie, just look at me, because they just pulled out the pistolas. Christ, they’ve got their weapons out and they start shooting them into the ceiling. Bam bam bam… I mean, the whole hotel was going berserk. So Ollie gets up and looks at them and says, ‘Very impressive. Well, watch this.’ He then does a handstand on the arms of his bar chair. I mean, from a sitting position, he goes straight up…. That’s a bitch. I mean, he’s a bull, right? So these same Mexicans put their guns away and applaud him. But Ollie gets carried away. He says, ‘That was nothing. Watch, one hand.’ So he pulls off one hand; I guess he forgot he was supporting himself on the chair arms, because of course the minute he takes off one hand, the chair loses balance, tips over, and he falls straight down on his shoulder. Man, he was in pain. I had to carry him out of there. But he’s the greatest drinker. He beats me by a long shot.”

Pam smiles and shakes her head.

“I hate it when Ollie and Lee get together. They’re both wonderful until they’re drunk, but then … Jesus … it’s unbelievable. He came to Phoenix once and we went up to see him, and they got so crazy that I ended up trying to hitchhike home. I mean, I’m Mrs. Lee Marvin, and there I am out in the 102-degree sun, dressed to the nines, just trying to get away from them….They were going really nuts that time.”

“Yeah,” Marvin says, laughing broadly. “I hate to see him show up, in a way. But I love the guy. He’s the best.”

Marvin sits back in his chair and stares out at the desert.

“Too many of the good old days,” he says. “I can’t make these scenes anymore. I’ve got to make them straight now. That’s the only way I can handle it. I’ve got enough shit floating around in my head without feeling that bad anymore. You know, when I was younger, I used to make problems for myself, like it was too easy. I mean, the reality of it was, I had to go out and get on a horse, and ride in, shoot the gun — how hard was that, right? So I’d get a little juiced and tell myself that the horse was going to try to throw me, and make it dramatic. I thought I was getting my creativity from the booze. Man, it was there inside of me all the time. That’s something I learned reading Jung … the collective unconscious….I can tap into that. Understanding my own dreams had a lot to do with getting me off the juice. Here, come inside. I want to show you something.”

Marvin and I leave the poolside and go into his dining room. In the wall are two paintings he did. One is blue with brown lines and a red splotch.

“I called this Country Roads,” he says. “I dreamed it. It seemed like this country road … these lines … but later, on a trip down in Texas, I realized that these brown lines weren’t roads at all. They were fire lanes. They were the machine-gun bullets coming from the ambush when my company got hit. I made this painting not to create art but to get it out. And this other one … I carved this one.”

The second painting is a labyrinth.

“It’s green and cream, like the hospitals after I was shot,” he says. “And the labyrinth — I guess that’s the wards, or different phases of my life. But it’s closed off. In some ways I never got out of that unless realizing… well, that kind of seals it off. I think maybe I’m into another phase of my life now. I’m not a great thinker or anything, but as you get older, the journey becomes more mental.”

“How will that affect your career?”

“Oh, I can still do it. I’m in good shape. In Death Hunt I was still able to put on the snowshoes and do it, except, you know, I’d suddenly find myself saying, ‘Christ, do we have to go up the hill again? Let’s go down once.’ The body starts to give out on you a little, but you make up for it because you’ve got a perspective and you’re cagey, and you know how to save yourself. You know there’s a lot of crap people say, like, when the bulls are no longer good and the women aren’t exciting, you should check out. Well, I say you should change your bulls and change your women. Life is too good to give up because it can’t be like it was. That’s why I don’t live on memory lane. Too many trips down there can ruin you.”

“Do you ever think about the palimony case?”

“No. I really don’t. I knew I was going to win. I was declared innocent, and they said I should pay $104,000. We’re appealing, because if you’re innocent, why should you have to pay anything? But if you mean am I bitter about it, the answer is no. It was a long time ago. I knew it was coming for seven years. And by the time it was on trial, I was married to Pam. It’s the same way with my movies. I do them, and I forget them. You can’t bring them home with you. Pam helps with that, too.”

Which is true. Pam Feeley was Marvin’s old childhood sweetheart. He used to drive her to school once he came home from the Marines. Then they both went on to other marriages. After Marvin’s affair with Michelle Triola, he went back to Woodstock, and, as he puts it, said, “Let’s go.” They’ve been together ever since.

The day I left, Marvin insisted on driving me to the airport. Despite his efforts to live in the present, he seemed haunted by the specter of his father. It was an early morning, and Marvin thinks best then. He is clear and full of energy.

“I remember this story about my father,” Marvin says. “He went out to Denver to see his father, who was dying in the hospital. It was Valentine’s Day, and they wouldn’t let him see him because he was already dead. My father slipped the card he had under the door. He never saw him again. And when the Chief died … I went down to Florida….He was in a coma … I came over and I kissed him on the head and said, ‘That’s it, Chief. I’ll see you down the line.’ And then I got on a plane, and guess what was playing: I Never Sang for My Father. People hated it, man, but I loved it. It got it all out there … Gene Hackman and Douglas … Melvyn Douglas is amazing. What a great actor. One of the greatest of all time. I remember that after the movie, people were saying how depressing it was, and I started an argument with them. I was holding forth, man to the whole plane. It was great. I got it out. Like that … I felt, you know, cleansed of it….”

He smiles, but there is still that haunted look in his eye. It’s as if he’s testing me. How much of this shit do you believe? Can you catch me when I’m performing?

As we waited for my plane to come in, we stayed silent for a long time. A friendship had started between us. That morning Pam had hugged me and said, “You feel like family; come back again, just for the hell of it,” and it was tough to break off. There were things unsaid about fathers and sons. People began moving toward the plane and Marvin said, “You can wait a minute. You know, Ward, I think I understand my father more every day. On some days I can almost….”

He broke it off there. Like he broke off talking about the marlin, or the moment in acting that words can’t reach, the moment when there is nothing that need be said because everything is right there, in sync.

Postscript

Of all the interviews I did Lee Marvin was by far the biggest surprise. I first saw Marvin when I was ten years old, living with my parents in Arlington, Virginia. My father was in an intelligence unit for the U.S. Navy, as he had been in World War II. So we went to movies at the naval base near Arlington. The movie we went to that Friday night in 1953 was The Big Heat. The star of the film was Glenn Ford, but I barely noticed him. What stuck in my mind were the two supporting actors, Gloria Grahame and Lee Marvin. The film has one of the most famous violent sequences of all time. Mobsters’ moll, Gloria Grahame, talks to the cops about some gang goings-on and to repay her, Lee Marvin, a vicious gangster, throws red-hot coffee into her face. I had never seen anything like it before. Marvin’s open-mouthed gangster was some kind of new species of vicious sadist. At the end of the movie Grahame gets him back by throwing coffee into his face, and very few things I’ve ever seen on the screen are that satisfying.

My father and I talked about Marvin all the way home. My mother said she didn’t think I should see things like that. She was probably right.

After that film I was a Lee Marvin fan for life. As far as I was concerned he was the best bad guy in the history of the movies.

Though I knew, of course, that actors weren’t the people they played, it never occurred to me that Lee Marvin would be much different than the guys he portrayed. I assumed he’d probably been born in a ditch somewhere, was raised by wolves, and had somehow gotten into the movies. Little did I know that Lee had actually been born into a wealthy family.

But, an even bigger shock. Not only was he a rich kid, but a kind one. We hit it off amazingly well, and started a real friendship. After my first trip to his place in Tucson we called one another on the telephone. Lee would stay up late, unable to sleep from the pains he had in his back. He would sometimes call me in the middle of the night, and say, “Hey, this is your reporter down in Tucson. What the hell are you doing anyway?”

I didn’t care what time it was. I was always glad to hear from him.

When my novel Red Baker came out he called me at 4:30 A.M. and said, “Jesus Christ, this fucking novel of yours is like looking at a corpse. You don’t want to but you can’t help yourself. I just spent the whole fucking night reading it.”

Coming from Lee, no comment could have been better.

Another time Lee called me in New York and said he was going to Russia to play the mink dealer baddie in Gorki Park. He announced that he’d be buying me dinner at the Palm, and told me not to try and pay for it or he’d have to work me over.

We met at the Palm in New York and had a great dinner. He’d been out of movies for a while and was thrilled to be playing a great part again. We ate steaks and of course people drifted over to get Lee’s autograph. Every single time they did he said, “Hey, you have to get my friend’s autograph too. He’s written a great novel and trust me, you’ll be glad you have it.”

I was so embarrassed my face reddened but Lee kept it right up. I signed about ten autographs while we ate.

And when we were done Lee wouldn’t hear about us splitting the check. That was the kind of guy he was, generous and kind. A sweetheart of a man.

And deeply sensitive.

I remember one phone call most of all. He called me at my girlfriend’s place in D.C. It was around two am. Lee was upset, his voice cracking.

“Man,” he said. “I just can’t fucking believe myself … Oh, man….

“What is it?” I said.

“This guy, he came up to me in the supermarket today. I was getting some steaks. He looks at me and says, ‘Lee Marvin, you don’t look so tough.’ ”

Lee stopped, and caught his breath.

“So?” I said.

“Well, I didn’t do anything. I didn’t slug him. I shoulda slugged him. I feel like such a fucking coward for not hitting him.”

“Awww bullshit,” I said. “You don’t have to prove anything to an asshole like that. You did the right thing, Lee.”

More silence.

“You think?”

“Fuckn A. Some asshole wants to feel big by taking on somebody who is really great. Fuck him.”

“Ahhh, Bobby, you’re all right.”

“Hey man, you’re my bud. Fuck that guy.”

There was silence on both sides. He knew I loved him like a big brother, and I knew the feeling was mutual.

1985 was a huge year for me. Red Baker came out, and through a combination of good luck and hard work I ended up going to Hollywood and working on the television show Hill Street Blues. I was already over forty, had hardly a nickel in my pocket and this was the biggest break in my life. So when my wife and I moved to Laurel Canyon I spent my first year working night and day on the show. I often thought of Lee but I didn’t call him except for a few times. I was obsessed with the show and making it in Hollywood. At forty-two I knew it was my last chance.

As the year wound down and I found out my contract was going to be renewed, I felt relaxed enough to get in touch with old friends again. I finally called Lee a couple of times and we talked but he was busy with guests at the house.

Almost six months more went by and one night I remembered how close we’d been and I gave him a call. He sounded even craggier than usual, and very tired.

“Hey, bud,” I said. “I’m in Hollywood. Sorry, I haven’t talked to you much of late but this has been a huge challenge, and all my energy is in it.”

He said it was okay, that he had been busy too … busy fighting serious intestinal problems.

“Oh, shit,” I said. “Is it bad?”

“They say it’s curable, Bob, but I don’t know if l believe them.”

“Lee, you’re gonna be okay,” I said. “I know you are.”

“Yeah, maybe. But, hey Bob, I can say one thing. No matter what happens at least I outlived that cocksucker Danny Kaye. He died last week, the prick.”

We both cracked up. I had never known Kaye but he was legendary in Hollywood for being a bully, and attacking people lower on the pecking order than he was. Just the kind of guy generous and kind Lee would hate.

Not long after Lee died. Those were the last words I ever heard from him. Funny, and fitting.

In my opinion Lee was one of the greatest actors of all time. When he was on screen you couldn’t look at anyone else.

But equally as important, he was a great guy, and a kind and generous friend. I did love him like a big brother, and miss him all the time.

[Photo Credit: Hans van Dijk via Wikimedia Commons]