Edward Hopper has long been a living classic of American art. This is not always the happiest fate for an American artist. Often it means only that a lucky formula was hit upon early in a career that was thereafter sustained by a ready audience. The history of American art is strewn with the corpses of artists whose success, won through the clever and persistent rehearsal of a single theme, masks a terrible paucity of energy and ideas. Yet in the case of Hopper, whose work is certainly not lacking in formulas and repetitions, this classic status has been well earned and looks assured for the future. The current retrospective exhibition of his work at the Whitney Museum confirms him as an artist of unique, if narrow, vision—a vision that bequeaths little to the aesthetics of paintings but which nonetheless penetrates American experience with a particularly incisive eye.

The Americanness of Hopper’s art is by no means fortuitous. It is a quality the artist has consciously pursued. Those dazzling bravura flourishes that were once the standard export of French painting and that, in Hopper’s youth, were still the distinguishing marks of high style among his ambitious coevals, are nowhere to be found in his own mature art. Hopper mastered his French manner very early, as the succulent surfaces of two pictures at the Whitney—“Le Pavillon de Flore, Paris” and “Le Quai des Grands Augustins, Paris” (both 1909)—make unmistakably clear. But from the twenties onward, he deliberately and painstakingly expunged this alien elegance in the interests of a native subject matter—and a native emotion—which the prevailing Gallic pastiche could hardly accommodate.

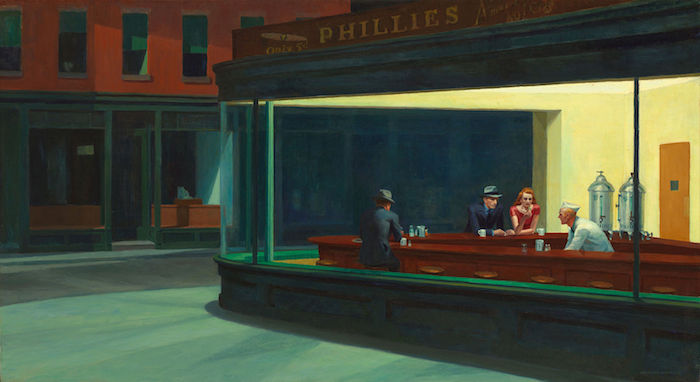

In the decade following World War I, Hopper settled on a vein of imagery that has been his special glory ever since. Recognizably American in its architectural and landscape subjects and in the character of its urban desolation, this imagery has established a repertory of scenes and motifs—the lonely, nocturnal glimpses of nearly deserted restaurants, theaters, and hotel rooms; the white clapboard houses and fantastic nineteenth-century mansions of New England, with their peculiar geometry of mansard roofs and dormer windows—which are now among the standard visual archetypes of our native imagination. Without investing it with false heroics or inappropriate rhetoric, Hopper raised this imagery to the level of poetry, where it stands free of both easy sentiment and facile historical encumbrances.

He approaches the composition of a painting rather as a theatrical director might set the scene of a play.

To effect so confident a transmutation of commonplace materials, Hopper developed a style remarkably dry, dispassionate, and plainspoken in its visual effects. At the center of this style is an obsession with light—the natural light of the sun as it defines the broad planes and gewgaw oddities of old houses, and the cold, artificial light of the modern city as it isolates moments of boredom, loneliness, and private ennui. Parker Tyler once spoke of Hopper’s method as “alienation by light,” and it is indeed this obsession—and his characteristic ways of accommodating it to the diversity of his subjects—that confers a vivid consistency on everything Hopper has produced in the last four decades.

He approaches the composition of a painting rather as a theatrical director might set the scene of a play. The specific mise en scène is selected—the lunch counter or filling station late at night, the hotel room early in the morning, the many-angled clapboard structure in the afternoon sun—and is then drawn in such a way that the crux of the pictorial drama consists almost entirely of the play of light and shadow in the scene depicted. Details are minimized and broad optical contrasts boldly emphasized in order to secure a maximum visual power from a relatively few pictorial elements.

It is Hopper’s skill in shifting the center of expressive gravity away from the sheerly anecdotal and onto this more purely visual drama of light and shadow that keeps his art from falling into literary theatricalism. And it is this same luminist rigor, together with his gift for a stark pictorial geometry which never engulfs its themes but, on the contrary, delivers them to the eye with a beguiling and affecting modesty, that separates Hopper from the multitude of inferior artists who essayed similar American subjects in the twenties and thirties. By exerting an incomparably greater visual pressure on the materials of anecdote, Hopper’s art transcends the limits of pictorial storytelling without repudiating the intrinsic human interest which such storytelling still holds, even for the sophisticated public.

Thus, while figures are not infrequent in Hopper’s pictures, they are almost never “characters” or personalities. They are never portraits of specific individuals who might interest us, even visually, apart from their pictorial roles. Hopper’s figures are mainly types rather than persons. Their pictorial function is to convey an emotion rather than a “biography,” and this is a function that, given the unity of Hopper’s style, they can discharge only by becoming fixtures in an environment they never dominate. Their presence sharpens but does not itself create the prevailing mood of Hopper’s world, as one can see easily enough in those pictures—among them, Hopper’s best—in which the atmosphere of alienation and ennui dramatically persists, even though there are no figures at all to be seen.

The exhibition at the Whitney, covering the period 1906–63 and consisting of paintings, watercolors, prints, and drawings, brings us many of Hopper’s most famous works, together with some—especially the prints and drawings—that are relatively unfamiliar even to Hopper enthusiasts. Among the former are “Gas” (1940) and “New York Movie” (1939), both owned by the Museum of Modern Art; “Nighthawks” (1942), from the Art Institute of Chicago; “Pennsylvania Coal Town” (1947), from the Butler Institute; and a dozen or more nearly perfect watercolors of New England houses. Among the latter are the rarely seen etchings Hopper produced in 1915–18 when he was doing very little painting. The exhibition—184 works in all—thus constitutes the strongest possible showing of an artist who has worked slowly but steadily for nearly sixty years, and is, incidentally, one of the most impressive events ever staged at the Whitney.

Certainly, Hopper’s place in American art history looks secure. His art continues the line of Eakins and Homer, and does so under conditions, aesthetic and otherwise, that have not been conducive to so forthright a confrontation of American experience. The mode he practiced could very easily have degenerated, as it did with so many of his contemporaries, into something utterly parochial and provincial.

Not the least of Hopper’s distinctions is the firm will with which he has sustained and purified his vision in the face of so many countervailing currents. At the Whitney, where his assembled life’s work creates a complete world of its own, one might be tempted to take this exemplary steadiness for granted.

But when one encounters his pictures elsewhere, particularly in those large surveys of contemporary American art—mixtures of fireworks and fire sales—which are among the minor afflictions of our cultural life, one has the exhilarating sensation of meeting an artist who knows his own mind, who sees the world with his own eye.

“Edward Hopper: An American Vision” is reprinted in Art in America: Writings from the Age of Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, and Minimalism, edited by Jed Perl and published by The Library of America. It appears here with permission of the Estate of Hilton Kramer.

[Painting via Wikimedia Commons]

Originally reprinted at the Daily Beast