… The sun was a golden globe, half-hidden, and as we drove along it appeared to be some giant golden elephant running along the horizon and I felt so good I remembered something Johnny Sain used to talk about.

He used to say a pitcher had a kind of special feeling after he did really well in a ballgame. John called it the cool of the evening, when you could sit and relax and not worry about being in there for three or four days; the job done, a good job, and now it was up to somebody else to go out there the next day and do the slogging. The cool of the evening.

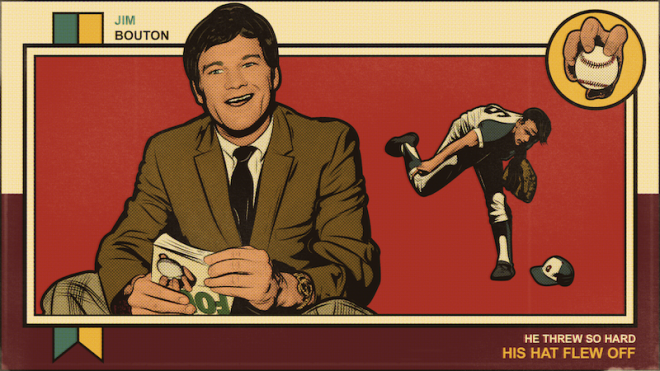

—Jim Bouton, Ball Four

The minor leagues. The pennants along the foul lines read Pawtucket, Toledo, Columbus, Syracuse—the AAA farm clubs of the International League. The outfield is surrounded by billboards promoting barbecue stands and Oldsmobile dealerships. A Lions Club baritone salutes the star-spangled banner fluttering in dead center field, and the crowd settles back for the first pitch of a doubleheader between the Charleston Charlies and the Richmond Braves.

Jim Bouton, former sportscaster, former actor, former author, former 20-game winner for the New York Yankees, arrives at his usual post at the edge of the bleachers’ behind the Richmond dugout. He can’t go on the field and he’s not willing to sit in the stands, so he loiters around the hot dog concession, looking around absently like a man who’s lost his bearings. At the age of 39, Bouton no longer resembles a fresh-faced Army recruit, as he did in 1964 when he won two games in the World Series. The hair is short again, but it’s graying, and the eyes are attracting crow’s feet. To the fans in Richmond, he must look like somebody’s dad trying to get a peek in the bullpen to see if his son is warming up. But it’s his own youth that Bouton is searching for, and tomorrow night when the anthem concludes before the exhibition game with the Atlanta Braves, Jim Bouton will walk to the mound and face a major league club for the first time in eight years.

Comebacks among baseball pitchers are not unknown, but they are rare. Tommy John did it after a surgeon rebuilt his arm in 1974, and Mickey Lolich is trying to do it now with the San Diego Padres, after sitting out a year. What makes Bouton’s attempt so exceptional is that he’s been out of baseball since 1970, and when he quit he wasn’t injured, he was washed-up. He hadn’t pitched effectively for six years. But instead of falling into the panic many ballplayers face when their careers are finished, Bouton wrote Ball Four, one of the best-selling sports books of all time.

He was censured by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and reviled by the baseball establishment. (“It’s the most derogatory thing and the worst thing for baseball I’ve ever seen,” Joe Cronin, then president of the American League, said of the book. “He’s got ballplayers sleeping with each other’s wives. He’s got them being Peeping Toms. He’s even got them kissing each other. I’ve never read anything so bad in my whole life.”) But a lot of ballplayers, even those who detested the book, gladly would have traded their seat in the dugout for a spot on the WABC Eyewitness News Team, or a part in a Robert Altman movie (The Long Goodbye), or a role in a TV sitcom (Ball Four, 1976’s short-lived series based on Bouton’s book). After all, what does a ballplayer have to look forward to when he’s out of the game? If he’s immortal, like Joe DiMaggio or Mickey Mantle, maybe he can do some TV commercials, but if he’s merely average, he’ll be lucky to land a high-school coaching job. From that perspective, Jim Bouton was the most conspicuously successful ex-ballplayer since Chuck Connors, who hit .239 for the Cubs but went on to glory as the favorite Hollywood actor of Leonid Brezhnev.

That’s all gone now, the television, the movies and even the money, sacrificed for a long-shot “comeback.” Last year he was cut by two minor league teams and finished the summer with a bunch of kids on a class A club in Portland, Oregon, at the lowest level of professional baseball; and since spring training this season, when he was released by the Braves, he has been pitching batting practice for meal money for the Richmond club—and that as a favor from Ted Turner, owner of the Braves organization.

The young players are nice to him, but he’s part of another world to them, a world of long-distance calls and funny tales about famous people. His equipment bag says “Washington Americans”—it’s a prop from his TV series, when he played Jim Barton, “number 56 on your scorecard but number one in your hearts.” The players kid about the yogurt he keeps in the icebox and the health food he eats on the road, but they admire the shape he’s in. At 165 pounds, he is 20 pounds lighter than his Yankee days, and his body is as lithe and springy as an acrobat’s. Still, it’s a mystery why Bouton is among them. He is not even on their roster. When the team flies to Syracuse, or Toledo, Bouton tags along, just to pitch batting practice and perhaps talk to the general managers of the opposing teams, letting them know he’s available. So far, no offers. “If I don’t make the big leagues soon, the money’s going to run out,” Bouton says. Today, the day before his big opportunity, Bouton sold his house in Englewood, New Jersey. “I’ve even taken all the money I put away for a college education for my kids, that’s all gone.” Tomorrow, if he doesn’t pitch well, the comeback of Jim Bouton is over.

The next morning Bouton wakes up and reaches for the baseball on his bedside table. There is always a baseball within his reach, and any spare instant, between bites of cereal or when he’s waiting for a light to change, he automatically grasps the ball, three fingers raised behind the seam in an eccentric knuckleball grip. “I needed to be by myself at this stage of my life,” he explains from the tousled bed in his two-room garret in Richmond. “I needed to be away from my family, to think about what I want to do with the rest of my life. Working on the TV series was extremely complicated and draining to me. I literally did not see daylight for months and months. When they cancelled the series I had to do something outside. I needed a goal, and it seemed like mastering the knuckleball was something worth doing.”

The knuckleball is the most elusive pitch in baseball. It is not thrown with the knuckles but with the fingertips; perhaps the name comes from the fact that the ball is tucked deep in the palm and the nails of two fingers are dug into the seams, with the consequence that the knuckles arch high above the ball—something the batter notices as soon as the pitcher begins his delivery. No one ever mistakes a knuckleball for any other pitch. When it leaves the pitcher’s hand he gives it a farewell push with his two fingers, and if he’s thrown it properly, it will float toward the batter with no spin at all. Spin is what makes a curve curve, or a slider slide. Spin adds velocity to a fastball and helps it move; a pitcher with a “live” fastball can expect his pitch to rise or fall depending on the direction of the spin. A ball without spin is a ball with no inclination to do any of these things. It is like a toy boat in a stream, without a rudder. Once it is set in the current, it is nature’s captive. A sudden gust from left field may push the ball several inches out of its path; the same groundswell that sweeps up the hot dog wrappers will lift the ball, and make it hop. A passing jet may leave a legacy of momentary turbulence—just enough to make a five-ounce ball shiver. Since a hitter has to commit himself within an instant after the ball is thrown, he is constantly adjusting his swing to the dips and dodges, so that he often winds up lunging after a ball that bounces in front of the plate. There is no such thing as a good knuckleball hitter.

Only four major league pitchers throw the knuckleball for a living: Phil Niekro of the Braves, his younger brother Joe with the Astros, Wilbur Wood of the White Sox and Charlie Hough of the Dodgers. Many managers won’t have a knuckleballer on their team. There’s too great a chance of a wild pitch or a passed ball, and because the ball travels so slowly, it’s an easy pitch for a base runner to steal on. If the pitcher makes the least mistake in his delivery and imparts a lazy spin to the ball, it will roll through the air like a cantaloupe—a batter’s delight. It is also an almost impossible pitch to teach. Most knuckleballers learned the pitch when they were kids, and practiced it for years before they played professionally. Hoyt Wilhelm, the old master, pitched knucklers in the big leagues for 21 years, retiring in 1972 at the age of 49; although he’s coaching now for a Yankee farm team in Tacoma, Washington, he hasn’t taught the pitch to a single kid. “It’s too late when they get to me,” he says. “Besides, you can’t teach it anyway.”

True knuckleballers are like psychics—invested with a power beyond their control.

Jim Bouton learned the pitch off the back of a cereal package when he was 12 years old, a package with a picture of Dutch Leonard that showed the orthodox two-fingered grip used by every knuckleballer other than Jim Bouton. “I went right out in the back yard to practice, but my hand was too small, so I used three fingers. As a result, I throw it harder than any of those other guys. Their knuckleballs float in there and may change directions two, three or four times on the way to the plate. When I throw it, it sort of pinches out of my hand like a watermelon seed. It has a slight torque on it, and it usually breaks only one time, and then at the last minute, and down.” After a year of practice, Bouton began to throw the knuckleball in Little League games. “I was probably the best 13-year-old knuckleballer in the country. I used to go around to high schools and bet the big kids that they couldn’t catch five balls I threw right at them. I’d throw them five straight knuckleballs, and they’d be lucky to catch even one.”

True knuckleballers are like psychics—invested with a power beyond their control. Phil Niekro, who may be the greatest knuckleballer of all time, has struck out 2,000 men with the pitch and still admits, “I don’t have any reason why the ball does what it does when it leaves my hand. I don’t make it do anything. It’s definitely a gift. I’ve been blessed with something very abnormal. Some guys have great legs and can run, some have great arms and can throw, some have great eyes and can hit. I’ve been blessed with the knuckleball, and the mind that can cope with it all these years.” In his book, False Spring, Pat Jordan analyzed the young Niekro who came up with the Braves farm team in McCook, Nebraska, 19 years ago: “Phil Niekro was the least complex man I’d ever met. He devoted his life to mastering a pitch…. A knuckleball is as impossible to hit when thrown over the plate as it is to throw over the plate. A pitcher has no control over the peregrinations of the ball. He imposes nothing on it but simply surrenders to its will. To be successful, a knuckleball pitcher must first recognize this fact and then decide that his destiny still lies only with the pitch and that he will throw it constantly no matter what…. It is a surrender that a more complex man could never make….”

All of his life, Bouton’s aggressive and self-centered personality has warred with the mystical knuckleball. When he grew up, he learned to drive fast and throw hard; and when the Yankees signed him they weren’t interested in his knuckler—they liked it best when he threw so hard his hat flew off and the ball popped the mitt like a cannon shot. Niekro and Bouton are the same age; in fact, they played in the same league in Nebraska, and Bouton remembers seeing Niekro warm up, and going over to him to talk about the knuckler. (Knuckleballers don’t keep secrets from each other, mainly because they don’t know the secret.) By this time Bouton had turned his back on the knuckler; and after that conversation with Niekro in Nebraska, he didn’t think about it again for nearly eight years, until his fastball died. “I never really used it again until 1967,” he recalls in Ball Four. “My arm was very sore and I was getting my head beat in. [Yankee manager Ralph] Houk put me into a game against Baltimore and I didn’t have a thing, except pain. I got two out and then, with my arm hurting like hell, I threw four knuckleballs to Frank Robinson and struck him out.” The next day Bouton was sent back to the minors.

Bouton spent the 1969 season writing Ball Four and throwing knucklers for the Seattle Pilots, a star-crossed major league expansion team. The next two years—his last in the big leagues—Bouton tried to refine the pitch, make it consistent. “My knuckleball was never as good as Wilhelm’s or Wood’s or Niekro’s, because I didn’t spend a lifetime working on it. But there were some nights I was good enough to strike out anybody.” Other nights, he wasn’t. Soon after Ball Four came out in 1970, Bouton was sent down again, this time by the Astros. And this time he quit.

Ball Four had hit the baseball world like a tempest. First there were the excerpts in Look, with Bouton’s frank appraisals of some of baseball’s biggest names, and exposés of what ballplayers really did in their spare time—notably, “beaver shooting” from the roof of the Shoreham Hotel in Washington, D.C. “The Yankees would go up there in squads of fifteen or so, often led by Mickey Mantle himself,” Bouton wrote. “You needed a lot of guys to do the spotting. Then someone would whistle from two or three wings away, ‘Psst! Hey! Beaver shot. Section D. Five o’clock.’ And there’d be a mad scramble of guys climbing over skylights, tripping over each other and trying not to fall off the roof. One of the first big thrills I had with the Yankees was joining about half the club on the roof of the Shoreham at two-thirty in the morning. I remember saying to myself, ‘So this is the big leagues.’”

“Looking back, I can only think I was overconcentrating. Super-overconcentrating. I’m going to really do good here. Put everything I got into it. Really throw the son of a bitch. Then I’d miss and try even harder on the next one. You can’t pitch that way.”

After the book came out, Bouton was booed whenever he got into a game, both by players and fans. Dick Young, the curmudgeon of the New York Daily News sports desk, called him a “social leper.” Bouton’s worst day came when he appeared in relief against the Mets in Shea Stadium. “As soon as I stuck my nose out of the bullpen in left field, the boos started. They washed over me like a flood of garbage,” Bouton wrote in I’m Glad You Didn’t Take It Personally, a book about the reaction to Ball Four. “This was, well, it was like walking into a wall, nose first.’ ”

“Let’s see if I can explain what that did for my pitching. Looking back, I can only think I was overconcentrating. Super-overconcentrating. I’m going to really do good here. Put everything I got into it. Really throw the son of a bitch. Then I’d miss and try even harder on the next one. You can’t pitch that way. Especially with a knuckleball. Sometimes, with the fastball, you get to throw… harder and harder the madder or more nervous you get. But the knuckleball—half of it was in the head. And all of my head was in the dugout.”

ABC offered him a job as a TV sports reporter. At first, he turned it down, but he reconsidered when he was sent to the Oklahoma City Eighty-niners and gave up six runs in the first inning of his start. “The knuckleball seemed to go home to wherever knuckleballs go home to,” he wrote. “Even Hoyt Wilhelm has the problem. Except his knuckler must live close by and take only short trips home. I think mine lived in Hong Kong.”

Most of the kids on the Richmond club were in junior high when the book came out, and for them the controversy it caused is some far-off event of another generation, like Kent State or the suspension of Denny McLain. When they speak of Ball Four they are usually referring to the television series, which was smothered in its seventh week, more or less to Bouton’s relief. “Gilligan’s Island in baseball suits,” he calls it. The experience soured him on television, and although he was still a very popular sportscaster (WCBS-TV in New York, his last employer, says there is an understanding that he is welcome back any time), he began to think there was something undone in his life. He felt caught in a meaningless rush. Perhaps if he focused his thoughts on a single pursuit—mastering the knuckleball, for instance—he might get a better grip on himself.

So now, at 39, when most of his contemporaries have left the game, Bouton sits in his attic apartment sawing teeth in his fingernails. It helps him get a better grip on the ball. (Niekro prefers to chew his nails; others let them grow long and toughen their fingers in pickle brine.) Nearby is a copy of Zen and the Art of Archery, which is Bouton’s spiritual manual. He is trying to temper the ego that kept him from becoming a great knuckleball artist; like the Zen archer, he is reaching for a state of “original agility,” which is accomplished only by withdrawing from all attachments whatsoever, by becoming utterly egoless: so that the soul, sunk within itself, stands in the plenitude of its nameless origin.” In this respect the humiliation of the last two years has been good for him, because humility is the key to the knuckleball. The pitch still hasn’t come to him, and probably it never will, but the search of it is Bouton’s way of finding inner peace.

Jim Bouton has the Richmond clubhouse to himself. It’s been a long time since he’s gone through this ritual—suiting up before starting a crucial game. “I’m breaking in a new jock strap for the occasion,” he jokes, although his voice is weak and he’s plainly scared. His old number 56 has been cut in half, and it doesn’t help his morale that the club mascot, Seymour Baseball, also wears number 28. Seymour Baseball wanders through the crowd during the games wearing a giant plastic baseball over his head.

“Three things can happen to me tonight,” Bouton says. “The first is that I don’t have a good knuckleball and I get my ass kicked. That’s the most likely. I haven’t thrown a good knuckleball all year, and since the guys won’t let me throw it to them in batting practice, I haven’t thrown one to a hitter since spring. Not to mention my pickoff move! If somebody gets on first, I don’t know what I’ll do.

“The second possibility is that I find it and have a magic game. I pitch seven innings, strike out five to seven guys, give up a couple of hits, maybe a run or two, but we beat the Atlanta Braves, 4 to 2. Right after the game Ted Turner comes in and says it’s an amazing game, and I sign a contract. I pitch a couple of games for the Richmond Braves to get sharp. then move into the big leagues, right into the starting rotation. That’s not really too farfetched. It’s happened to me several times before. It happened with the Yankees when I was one of those kids invited to the major league spring training camp, to pitch batting practice. We went to St. Petersburg to play the Cardinals, and the Yankees brought three pitchers along to pitch three innings each. They didn’t have anybody to pitch extra innings, so when it went into the tenth they asked me to throw. I wound up pitching five scoreless innings, and they had to give me a chance. Maybe that’s what will happen tonight.

“The third possibility is in between—I pitch well enough, but nothing super. That’s the one I try to keep out of my mind.”

Out in the bullpen, the pitchers for the Richmond Braves await Bouton’s appearance. In the meantime, they listen to snake stories from Luke Appling, “Old Aches and Pains,” as he was known when he played shortstop for the White Sox. Luke is 71 now, a “roving batting instructor” as he describes himself. Joey McLaughlin, one of the young pitchers on the staff, asks Luke what he thinks about Bouton’s chances. “Well, he’s got his knuckleball, but it don’t flutter. It curves down. I’d rather see it flutter.” The pitchers nod. They all wish Bouton well, but if he does really well, one of them is likely to be cut.

By a happy coincidence, Bouton’s old pitching coach with the Yankees, Johnny Sain, is now coaching at Richmond. “The comeback trail is a hard way to go, ’cause you just about have to have instant success,” says Sain, who is famous for rehabilitating worn-out pitchers. “Jim’s trying to do what nobody else has ever done. He’s prob’ly got more pressure on him tonight than he’s ever had in his life, more than when he pitched in the World Series.” Since Bouton came to Richmond, Sain has been teaching him to economize his motion by using the same “quick pitch” windup Sain taught Jim Kaat, who’s used it very successfully with the Phillies. It helps Bouton concentrate on the moment of release. Sain has also taught Bouton a new pitch, the “cut fastball,” which is thrown slightly off-center and tends to break away from right-handed batters. Every knuckleballer needs something for those times when the knuckler deserts him, or when it’s working so well that it seems to have a magnetic repulsion for the strike zone. “Jim’s got a good fastball, slider, and a good palm ball—that’s his off-speed pitch,” Sain says. “He throws well enough to fill in with these pitches, if he needs to.”

Today, the batting practice pitcher for the Richmond Braves is Tommie Aaron, the manager of the club, Hank’s younger brother. Years ago, Tommie and Jim Bouton played AA ball together in the Texas League.Tommie is happy to have Bouton pitch tonight because he won’t have to waste one of his starters on an exhibition game. “I’m planning to pitch him six or seven innings,” he says.”But I’m not gonna let it turn into a farce. If they get two or three runs, okay—but I’m not gonna let him get his brains knocked out.”

The Atlanta Braves arrive at the stadium, and all the sportswriters rush to interview Ted Turner. As a stunt, Turner is going to umpire third base tonight. A lot of people think that pitching Jim Bouton is also a stunt. In the Braves organization, Bouton’s opportunity with the Richmond farm team is called a “presidential decision,” meaning that everybody else in the front office thought it was a bad idea. The Braves are involved in a “rebuilding,” and the director of player development, Hank Aaron, could be forgiven if he didn’t see where a 39-year-old knuckleballer fit into a youth movement. When he was released earlier this year, Bouton flew to Atlanta. “I spent 15 minutes in Ted’s office,” Bouton recalls. “I said, ‘Ted, I had the best spring of anybody in camp. I willed it to happen.’ I explained how I thought I could help him.” Turner was sympathetic. He and Bouton have many things in common, mainly enemies. They are both outcasts in organized baseball, and both have been censured by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. “Ted picked up the phone,” Bouton recalls, “and spoke to Bill Lucas [the director of player personnel] and said, ‘Find a place for this man. He’s no dummy.’ ”

Lucas remembers the episode. “Ted had a hunch about it,” he says wryly. “Ted owns the ball club.”

In Richmond tonight, Turner fields questions restlessly, using the chance to extol his team, which is in the cellar for the third straight year. “One good thing about ’em, they’re almost all Americans—not to take anything away from the Latin players, of course—but this way we’re helping the dollar deficit.” Most of the writers came to see Bouton, and they want to know what his future is with the Atlanta Braves. “If he does well,” Turner says, “it’ll pose more problems than anything else. We’ll be able to place him somewhere, I guess. You know last year we weren’t exactly knee-deep in effectiveness where pitching is concerned. If he doesn’t do well, the problem is that he’ll probably hang around for awhile.”

“But he’s 39, Ted,” says one of the writers. “Don’t you think he’s over the hill?”

“We’ve already got one 39-year-old knuckleballer on our staff in the person of Phil Niekro, and he led the league in strikeouts last year. I’m 39 myself, and I may not be able to pitch a ballgame, but I can sail pretty decently,” says the Yachtsman of the Year, and winner of the America’s Cup.

Jim Bouton comes out of the clubhouse and stands where he usually does, behind the players’ gate; only tonight he’s in uniform and the autograph hounds engulf him. The uniform makes him look older. At last, the field awaits him. The grounds crew has been at it all day long, and now they’re cleaning up from batting practice. “I’ve always liked the idea of walking across a field with the organ playing and the dew on the grass,” Bouton muses. “ I remember thinking as a kid, wouldn’t it be great to run out there and slide into second base! It’s such a nice place to be. You can tell at once that it’s set up for a game of some kind—the manicured grass, the nice white lines, the men in uniforms, the mound being built up—you know something important and exciting is going to happen there. They sure don’t prepare offices like that for people to come to work in the next morning.”

“Hey, Dad!” Bouton turns around to find his wife and two sons, Mike, 14, and David, 13, who have driven down from New Jersey after spending the entire week packing boxes and moving into a smaller house. (His 12-year-old daughter. Laurie, had to stay for a gymnastics meet.) Although he’s asked for a lot from his family, Bouton insists his comeback attempt hasn’t hurt them. “They don’t have the stereos they want but they do have bicycles,” he says.”And when they open up the refrigerator there’s still food in there.” What they miss is a father—and occasionally his kids have to remind him of that.

For a moment in from of his family, Bouton lets down. “I wish I were somewhere else, sucking my thumb,” he jokes. “No, not really.”

“Watch out for Jeff Burroughs,” Mike warns. Jeff Burroughs is hitting .416 and is the hottest hitter in baseball.

“Thanks, Mike.”

He thinks about something a pitching coach once told him: Never worry about a thing, boy. Always remember that there are 600-million Chinese who don’t give a shit.

Bouton kisses his wife and walks down to the bullpen to warm up. “This is sorta like sudden death,” Bobbie Bouton mutters as he leaves.

Mike nods. “Well, we could use him at home.”

The ground is still wet from three days of rain. Bouton looks up at the flag in center field. It hangs absolutely dead. His heart sinks. The wind has been blowing out all day, which for Bouton’s knuckler is the very best condition. When he throws into the wind, the resistance makes his pitch go crazy. When it’s dead like this—well, a little wind would help. He throws a knuckler to his catcher, Bruce Benedict, and nothing happens. It doesn’t break.

Bouton’s family sits in the courtesy boxes, with all the front-office people from Atlanta and the Richmond ballplayers’ wives. Already there is quite a large crowd. On the field, the notables are being presented, including Hank Aaron and Brooks Robinson, the former third baseman of the Orioles, who is on hand to promote Crown Oil. Baseball is a strange fraternity. “Old Aches and Pains” Appling sits just in front of Bobbie Bouton, with a broad scowl on his face (perhaps he expected to be introduced on the field), and just behind her, one of the ballplayer’s wives is cuddling a baby. “I feel pretty out of place,” Bobbie says. “Her baby is just cutting a molar, and Mike is working on a wisdom tooth.”

Mike and David cheer when Ted Turner is introduced in his umpire’s uniform. “I hope Dad makes it,” David says. “I know the odds aren’t too good.” Mike uses the field glasses to watch his father warm up. “Uh-oh. He’s not throwing major league stuff.” Mike sees his father shake his head and mutter into his glove.

Bouton is reminding himself: Don’t be so mechanical. This is your kind of game. You’re the old “Bulldog,” the man with the 1.48 ERA in three World Series games. Then he thinks about something a pitching coach once told him: Never worry about a thing, boy. Always remember that there are 600-million Chinese who don’t give a shit. He smiles. If the worst thing happens, he does have a contingency plan, a sort of revenge upon the American baseball establishment. This year Ball Four is being translated into Japanese. In his imagination Bouton sees himself going to Japan and teaching the knuckleball. “I’ll be the Johnny Appleseed of the knuckleball. And the Japanese, with their intense dedication, master the pitch. A team of 25 diminutive players with an entire knuckleball staff comes to the United States and humiliates the world champions. It’s the perfect pitch for them; it requires delicacy, single-minded dedication and twice as much work. It’s the equalizer of the little man. I mean, they’re ripe for it! It’ll be worse than Pearl Harbor!”

This reverie is interrupted by the national anthem. Bouton suddenly realizes that Bruce has caught only about half of the last ten pitches. The ball is breaking everywhere. It’s the best knuckleball he’s ever thrown.

“Just sitting down, I had a déjà vu,” Mike says when the anthem is over.

“A good one?” David asks.

“I don’t know.”

Bruce Benedict managed to borrow the huge knuckleball mitt that the Atlanta catchers use when Niekro is pitching. The pocket of this mitt is so large that an ordinary catcher’s mitt will nearly fit inside.

As he walks to the mound, Bouton notices Turner standing behind third base with a giant chaw of tobacco ballooning in his cheek. Turner waves to him. Bouton laughs. He feels he is in a dream. He hears the batters announced over the PA, but their names don’t register with him. He is thinking only of the pitch, each pitch. He finds the familiar grip inside his glove, concentrates on his motion and watches the ball sail toward the catcher’s mitt.

The first batter for Atlanta is Jerry Royster, a .310 hitter, who watches two knuckleballs hit the dirt, swings at two that don’t, and when the count goes to 3 and 2, strikes out on a cut fastball, the first cut fastball Jim Bouton has ever thrown to a major league hitter. Biff Pocoroba grounds out to second base, and that brings up Jeff Burroughs. “I was aware it was Burroughs, but I couldn’t think uh-oh, big powerful hitter with a compact swing,” Bouton said later. “Especially since I know that adrenaline doesn’t help. Like, the more you back off, the better it works. With the archer, the harder he tried to shoot the bow, the harder it became.” Burroughs takes a ball, fouls off a cut fastball, misses a palm ball and strikes out on a knuckler. Three up, three down.

Bobbie laughs. “Even if from now on it’s not like that, that was fun!”

“I can just see the headlines tomorrow morning in the Bergen Record!” Mike says.

The PA announcer says there is still standing room available in the picnic areas. Mike looks around. “Boy, this place is jammed,” he says. Every seat is taken and people are crowding into the aisles. The line to the ladies’ room is 50 feet long. When Bouton comes to the mound again, the crowd cheers. The PA announces that any ball hit into the crowd in right field will be a ground-rule double. The crowd in right field? Bouton looks around and sees hundreds of people standing behind a rope inside the warning track, stretched all the way to the flag in center. The outfielders look at the crowd and shrug. And more are coming in.

Mike jumps out of his seat. “Mom, I gotta go out there!”

In the second, Richmond goes ahead 1-0 and gets two more runs in the fourth. By this time the crowd is cheering Bouton’s every pitch. “Every time I’d come into the dugout the guys would look at me different than I’d ever seen them look at me,” Bouton said after the game. “Like, what the hell’s going on here, Bouton? You know, they’d been looking at me as such a pathetic figure, throwing batting practice for nothing, almost a forlorn character, really. Now they really started to look at me funny. After the fifth scoreless inning, Joey McLaughlin finally says, ‘Hey, Jim! What kind of yogurt was it that you’ve been eating?’ It cracked everybody up.”

“When he left the game, I can honestly say l felt chills,” says Bruce Benedict, the catcher. “It’s something I’m gonna always remember. If he’d pitched in any prior games, he might have gone all the way.”

In the sixth, Bouton strikes out two men, walks one, then gives up a hit that scores. Atlanta’s first run. “He’s got to be getting tired,” Bobbie says. “It’s the sixth inning and he’s thrown a lot of pitches.” Pat Rockett, the Atlanta shortstop, ends the inning by flying out to center. The next inning, Bouton gives up a walk and a single, and Tommie Aaron knows it is time to take him out of the game. He leaves leading 3-1. He has scattered seven hits, walked three and struck out seven. Altogether he has thrown 114 pitches, 65 for strikes. When Bouton surrenders the ball, the crowd—those who are not already on their feet—stands and cheers. Bouton tips his hat in the standard acknowledgement, then suddenly stops and waves the cap over his head, with the non-ironic grin of a man whose highest point has come as a non-roster player for the Richmond Braves.

“For this is what the art of archery means: a profound and far-reaching contest of the archer with himself.”

Later, undressing in the clubhouse, Bouton tells the crowd of reporters, “I’m not going to say that this makes everything worthwhile, because I enjoyed it all—being outdoors, in Knoxville, Durango, Portland, learning the knuckleball. I wasn’t trying to prove a point, but I do think I can play for another 10 or 15 years. Why can’t I pitch past Wilhelm? Why can’t I pitch till I’m 55? Who knows what the limits are until they’ve been tested?”

“When he left the game, I can honestly say l felt chills,” says Bruce Benedict, the catcher. “It’s something I’m gonna always remember. If he’d pitched in any prior games, he might have gone all the way.”

Bouton smiles at him. “We had some fun, didn’t we?”

“Hey, you’d think we won tonight!” somebody laughs. Richmond lost the game in the ninth, 7-3.

Hank Aaron and Bill Lucas are a bit chagrined, though quite complimentary. “If I was a scout, my opinion would be that I’d be demoted,” Lucas says.

There are still questions about what Bouton’s outing proved. Although he did well, it was only an exhibition game against one of the weakest teams in baseball. And even the Braves weren’t entirely convinced.

“Well, his fastball’s too slow,” Jeff Burroughs says. “He’s got good motion on his pitches, good control—really, it’s surprising how good his control was. Honestly, you’ve got to think he’s a little crazy to be doing this, but most of us who play the game are a little crazy. There’s really not a more fun way to live your life.”

(At least Bouton’s performance in Richmond was good enough to win him a contract with the Savannah Braves, the AA farm team one level below Richmond. A week later, on May 19, he won his first official game, beating the Nashville Sounds. He went the full nine innings, gave up six hits, struck out eight and walked none. Afterwards, Savannah manager Bobby Dews said, “I think if he keeps pitching like this, Ted Turner will bring him up to the big leagues.”)

Maybe Turner will bring Bouton to the majors. He seems swept up by the improbability of Bouton’s quest. After the exhibition game, the owner takes his entire Richmond club out for rib-eye steaks. (Bouton orders crab cakes.) In the restaurant, Turner is expansive—more expansive than usual—because his hunch has paid off.

“We’ll find a place for you, don’t worry,” he tells Bouton. “You know, pitching is like pussy—you can never get enough of it. Maybe we’ll trade you to the Yankees for Graig Nettles. Uh-oh, I forgot. You’re not even on the roster.” He throws a baseball at Bouton that he’d gotten autographed by the umpire crew. “You’ll probably want a million dollars.”

Bouton grips the ball and looks at his wife. “The cool of the evening,” she says.

Bouton smiles. “The cool of the evening.”

[Illustration by Sam Woolley/GMG]