One by one, day by day, they’d glide to the witness stand, this procession of improbable women, a spangled harem of them, drifting into the courtroom and out again, leaving the scent of their perfume and the shadow of their glitter and the echo of their cool. Week in, week out, they never stopped coming.

That was the extraordinary thing. How many there were. The final count stopped short of thirty—that was the number of photographs of women Rae was said to keep in a box at home—but there were more than enough of them to make each and every morning worth my springing out of bed for, worth walking down to the courthouse for, worth getting frisked at the doorway for: in the hope that a new one might illuminate the somber courtroom with its smoked-glass view of the jailhouse across the street.

And sure enough, in the middle of a gray day of testimony filled with the babble of a psychologist or the grunt of a jail guard or the platitudes of a coach, out of the blue Rae’s attorney would suddenly say, “The defense calls Dawnyle Willard,” and next to me the TV guy would arch an eyebrow at the local columnist—who’s this one? what’s the angle? lover? friend? cleaned his apartment? helped him jump bail?—and they’d both shrug, because no one had heard of Dawnyle Willard.

Then everyone would turn to the back of the courtroom to get a look at the newest entrant, because we just knew she was going to be beautiful. And honestly, she just about always was.

Dawnyle certainly was. Stately, slim, a dancer. Former girlfriend, now confidante. Wept on the stand, at the pure goodness of the man.

Amber was cool, slim, and fiery and a favorite among those of us who spoke of such things during breaks in the action, although Starlita was easily the most exotic; she looked like a Mexican princess dropped into a southern murder trial. Michelle was the pretty little girl next door. Monique was innocently cute. Trisha, Rae’s current squeeze, was … well, a tad young looking. But she was pretty enough for you to understand why Rae would nod at her each day when, sandwiched by grim bailiffs, he left the courtroom—nodding as if to say, Hey, babe, don’t worry: you’re the one now. And I swear, she believed it.

Sometimes, though, Rae nodded at the woman in the front pew. She was there every day. By some measures, she was the most handsome of all: high forehead, piercing eyes, coiffed and jewelried to the highest. Some newcomers to the courtroom thought she was another female friend. But this was Rae’s mother, Theodry Carruth, anchoring the Cult of Rae from the center of the home-team bench.

Really, there was no other way to think of them—other than as a cult—at least not after the mother of one of Rae’s former girlfriends took the stand near the end of the trial, and the mother was gorgeous. Not only was she beautiful, but get this: after her daughter testified against Rae, the mother testified glowingly for Rae.

And then, as she left the stand, she looked right at Rae—a man facing the death penalty for taking out a hit on a pregnant woman—looked right into his eyes and, all sweet and wet, mouthed the words I love you.

As the weeks passed and the women came and went, I would look over at Rae and stare at his profile, which never changed, because Rae never changed expressions, even during the closing argument, when the lead prosecutor played the 911 tape of Cherica Adams’s moans: sounds from beyond the grave, all sputtering utterances, atonal syllables so skin-crawling that throughout the courtroom shoulders heaved in sobs. But Rae’s face flinched not at all. Animated and emotional and expressive as the women were—weaving and looping their tales of his goodness and his charity—Rae remained a well-tailored sphinx.

And so, day in, day out, I’d ask myself a question. Not what they all saw in him; the first look at Rae explained that: this baby face, the contours all smooth and rounded, the outward downslant of his eyebrows giving him this puppy-dog-swatted-with-a-newspaper look. Girls loved to take care of Rae even before he became a millionaire. No, the question I kept asking myself was this: If Rae Carruth loved women so much, why did he keep threatening to have them killed? How, if he gathered women around him like a cocoon, if he thrived on them and fed on them and drew sustenance from them, could a man get to a point in his life where he routinely considered disposing of them? And how could such a man wind up finding a home—even flourishing—in the National Football League?

Well, because he really didn’t like women at all. (He liked to fuck them, and he liked their attention, and he liked the idea of them, but he didn’t like them.) And because he was accustomed to violence. And because he was making a living in a league in which a man and his basest instincts are encouraged to run wild. Well, he was until recently, anyway; Rae doesn’t play football anymore. He’s in prison up in Nash County, where he won’t have to worry about women and women won’t have to worry about him, and as his crime swiftly seeps into the background noise of the culture, we’re already starting to act as if we didn’t have to worry about Rae Carruth anymore. As if the whole episode were an aberration.

Of course, it’s anything but. Take even a cursory look at how Rae Carruth went from first-round NFL draft pick to ward of the state of North Carolina, serving a quarter century of hard time for conspiring to commit the most horrific crime in the history of professional sports, and the question is not how it could happen but when is it going to happen again.

Football is a violent sport, growing far more violent and mean and attitudinal every year, and it has been played by men who have traditionally been violent against their women. This has been the case since Jim Brown, the greatest running back ever to play the game, garnered the first of a half-dozen charges of violence against women, ranging from spousal battery to rape to the sexual molestation of two teenage girls. Brown, who has never been convicted of a single charge, begat O.J., the second-greatest running back, who, at this writing, continues to seek out Nicole’s true killers. O.J. begat Michael Irvin of the Dallas Cowboys, who, prior to one of his frequent cocaine-sex bacchanals a few years back, cavity-searched one of his girls a little too hard for the liking of her cop boyfriend, who then took out a hit on Irvin. It wasn’t just Irvin who dodged a bullet that time. It was the NFL, which retired Irvin with pomp and circumstance.

This year, of course, Super Bowl MVP and murder defendant Ray Lewis, who has twice been accused—but not convicted—of hitting women, commanded headlines and earned full forgiveness at the hands of a most understanding media machine. Wearing a Giants uniform in the same Super Bowl was Christian Peter, a man accused of so many crimes against women in college that public outcry forced the Patriots to drop him within days of drafting him in 1996. Lost in the shuffle but not forgotten, Corey Dillon and Mustafah Muhammad and Denard Walker contributed, each in his own way, to this long-standing tradition. On the day he ran for a record 278 yards, Cincinnati’s Dillon, now arguably the game’s best running back, was facing charges of striking his wife; after the season, he plea-bargained to avoid trial. His uniform was sent to the Hall of Fame, where it now keeps company with the memorabilia of Brown and Simpson. As for Walker, he played for Tennessee last year after being convicted of hitting the mother of his son. He then declared himself a free agent and was courted by several teams until the Denver Broncos anted up a cool $26 million. Muhammad, a cornerback with Indianapolis, led his team into the playoffs last year after being convicted of hitting his wife. And let’s not forget the domestic-assault conviction of Detroit’s Mario Bates or former Packer Mark Chmura’s troubles surrounding his dalliance with his seventeen-year-old baby-sitter.

When the NFL parades its first-round draft picks to a podium on national television and slathers them in their first frosting of celebrity, its message effectively and immediately neutralizes all the good-behavior seminars.

And what about the more subtle misogyny embodied by the late and revered Derrick Thomas of the Kansas City Chiefs, who was killed in a car wreck two years ago? He left behind seven kids by five women, and no will—thus no guarantees of money or consideration for any of the children or any of the women.

The NFL claims it is doing more than ever to educate its recruits. Its preseason three-and-a-half-day symposia are supposed to make its rookies duly aware of their newfound responsibilities to their fans and their leagues and the kids who put their posters on the wall: To avoid the sleaze joints. Steer clear of the hucksters. Grow up quick.

But what is it really doing? When the NFL parades its first-round draft picks to a podium on national television and slathers them in their first frosting of celebrity, its message effectively and immediately neutralizes all the good-behavior seminars. On that day, the commissioner is not only handing each of the players a guarantee of several million dollars; he is also giving them the whispered assurance that the league likes them just the way they are. No need to grow up too fast.

Ultimately, the league refused to ban Ray Lewis and his brutal peers because it needed them on the playing field, and that mandate speaks more loudly than a lecture about good citizenship—especially to a remarkably immature kid like Rae. After all, little boys don’t like little girls, and what was Rae Carruth other than an overgrown boy, a bundle of muscle and fiber jerry-rigged to play a game? Of course, most kids grow out of that stuff. It’s the rare one who is allowed to harbor his playground sexism until it blossoms into monstrosity.

He came from the place so many seem to come from; only the details vary from kid to kid. Rae didn’t grow up with his biological father. As a child, Rae split time among several houses, including his mother’s, set in a neighborhood of squalor and dismay on the south side of Sacramento—on an avenue where vandals routinely set cars aflame—and her sister’s place in a nicer part of town, absent the bars on the windows. Even then, even before he was showered with privilege, Theodry worried about the sharks and the vultures preying on her son, “the guppy.”

This is how she describes him. This is why she describes herself as “the piranha” when it comes to protecting her son. To know Rae Carruth and to understand the course he chose to take, to divine the nature of his particular rebellion—because isn’t that what all our adolescent contrarinesses are? rebellion against what was lacquered onto us beforehand?—you must first know Theodry Carruth. There is a hardness and a strength to her, and they seem like the same thing; she seizes the space she is in and commands it from on high.

But if one may be tempted to call Rae’s mother domineering, one ought not to, because she will not tolerate being described as overbearing, and she will tell you so. Describe her instead, she warns in a voice that brooks no argument, as simply having been raised by a Southern mother, and then say she is raising her son thusly.

Theodry Carruth’s vigilance over her only son’s upbringing paid off at least in the short run: Rae’s grades at Valley High School were solid, he stayed out of trouble, and big colleges came calling. In 1992 Rae went off to the University of Colorado. Back on the infernal block on Parker Avenue, Theodry Carruth turned one of the rooms into a miniature shrine where family and friends gathered to sit in mock stadium chairs and watch Rae’s games from Boulder. It was called the Rae of Hope room. Neighborhood kids would set it on fire a few years later.

At Colorado, Rae’s coach Bill McCartney was a demagogue. On the field, McCartney was known for teams that played hard and thuggishly. Off the field, he was known for the conversation he’d had with God. One day God told McCartney to found the Promise Keepers. Soon thereafter, at McCartney’s urgings, tens of thousands of fathers and husbands took to gathering in football stadiums across the land to beat their chests and flagellate their souls and collectively recommit to their gender. The subtext of the Promise Keepers was a patently sexist one, of course: portraying women as worthy beings but regarding them, ultimately, as secondary, as biblical chattel.

But beneath the roar of McCartney’s fire and brimstone, his daughter was getting pregnant by two different football players in four and a half years—the first, the star quarterback, wanted her to abort the fetus; the second sired his child during Rae’s freshman year. This only proved that when you climb too high in the pulpit, it’s easy to ignore the funky stuff going on under your nose. Especially if you’re a member of the sinning crowd: McCarthey himself quit on his Colorado contract after Rae’s third autumn in Boulder. Broke his promise, if you will.

He could be a real joker, or he could be a cipher, or he could even be, in the dark moments, the Devil himself.

Rae’s college athletic achievements were legendary—in one game alone, he had seven receptions for 222 yards and three touchdowns. In 1997 he entered the hallowed fraternity of first-round draft picks under the watchful wink of the NFL. The Carolina Panthers took him as their first selection, number twenty-seven overall. Like all rookies, he would be instructed on how to behave. But like his first-round peers, he knew what had actually just happened: he’d been ushered into a land of entitlement, where the only promise he’d really be held to was the promise he’d shown thus far on the playing field.

The Panthers gave him a four-year contract worth $3.7 million and a $1.3 million signing bonus, and it wasn’t so much the amount of money that was stunning but the ease with which it came. Within days of being signed, Rae got a check for $15,000 in the mail from a trading-card company. Just for being Rae. How sweet was that?

He immediately signed it over to his seventeen-year-old girlfriend in Boulder, Amber Turner, and told her to go ahead and set up house for them in Charlotte. Amber was a stylish and precocious beauty, a high school senior. (Even as a fifth-year college senior, Rae’s tastes still tended toward postadolescence.) His girlfriend in high school, Michelle, had been a sophomore when he was a senior, and she’d just turned eighteen when Rae got her pregnant on a visit back home from college. He’d waffled about whether or not to have the baby from day to day. Michelle wasn’t surprised at his indecision. She says she knew him as a man of many moods. He could be a real joker, or he could be a cipher, or he could even be, in the dark moments, the Devil himself.

Amber Turner knew about the baby back in Sacramento. Amber also knew Rae said the boy might not be his, and even if it were his baby, he said, there were ways to fix the blood tests.

And what of the parents? Amber’s mother had no problem with Amber setting up house with Rae in a distant city, right out of high school. She loved Rae, too. He was polite and civilized and kind. He called her Mrs. Turner even after she said he could call her Barbara.

Rae’s mom, Theodry, was pleased, too—pleased that her only son would be living in a Southern town with family values. But it wasn’t family values that Rae found in Charlotte. It was what all young, wealthy, transplanted men find there, these strangers in a strange land: nightclubs, comedy clubs, strip clubs. Charlotte is full of gentlemen’s clubs, peopled by men who are anything but. On the high end, there’s the Men’s Club, Charlotte’s topless palace nonpareil.

The Men’s Club, planted right off the interstate, like everything else in a town laid down like a new quilt of plywood and Sheetrock, is a sumptuous palace of fiction. What the Men’s Club lacks in poetry it makes up for in excess. The red-felt pool tables are illuminated by hanging lamps ensconced in blue glass. The lobby boutique is filled with expensive clothes for men and women. The kitchen will serve you a fillet medallion sautéed in a mushroom demiglace.

In the center of the place, beyond the sunken bar, is the main stage. But the dancers are not the only attraction; above the stage looms a huge television screen, like Oz’s mask, eternally tuned to ESPN, so that the allure of even the most seductive sirens competes with huge images of men being tackled and talking heads blathering about blitzes. In a very real sense, the women at the Men’s Club are just another product, with this exception: there is nothing real about them. The tattoos on the soft planes south of the hipbones are frosted over with pancake makeup. Their names are as false as their chests. They are stage actors. They are not meant to be the stuff of reality.

This, of course, explains why Rae sought them out. Because they seemed to be less than real women yet possessed of the necessary female attributes. So that considering their feelings was a less complicated process.

Despite a terrific rookie season on the field—Rae earned a starting position at wide receiver and finished with an impressive forty-four receptions—Rae’s home life soon proved rocky. Amber went home after that first season. He found her too possessive: she was jealous of all his other female friends. And there would be many female friends. There was Starlita, whom Rae had so charmed in a barbershop one day that before she’d finished having her hair done, Rae had taken her young son down the street for pizza. Soon Starlita thought Rae was the best thing in Jacobe’s life. Rae was worried that Starlita was turning her son into a mama’s boy. (Rae always harped on that. And what was Rae if not a mama’s boy?) There was Fonda Bryant, who kept a picture of her son on her desk at a radio station Rae visited one day, and before long the boy was spending nights at Rae’s. Rae was exactly what the boy needed; Rae was firm about staying away from alcohol and drugs, firm about making sure the boy did his homework. When they played, Fonda couldn’t tell who was the kid and who was the adult.

He didn’t carry out all the threats, of course. He was a joker. He just talked about it a lot—about having Michelle and Amber killed.

And yet Rae hardly ever visited his own child. He gave Michelle grief about breast-feeding the kid and hugging him so much—he worried she was making Little Rae soft. So Michelle sued him for child support: a judge granted her $5,500 a month. She offered to lessen it if Rae would come home and visit more. He promised. He didn’t. In the meantime, Amber went back to Charlotte for a quick visit. She got pregnant. As Rae’s responsibilities and missteps threatened to collide, as his little-kid appetites met his stunted ability to cope with adversity, he began to consider a solution both novel and bizarre on the surface but certainly logical in the context of a man who regards his women as disposable and dispensable: any time he’d get a woman pregnant, he’d threaten her with death.

He didn’t carry out all the threats, of course. He was a joker. He just talked about it a lot—about having Michelle and Amber killed.

Like the time Michelle called him in March 1998. She’d been unsuccessful in persuading Rae to come back home to visit their son. Rae had another idea. He suggested the two of them fly east to Charlotte. Fine, she said. I’ll rent a car and see the sights while you play with your son.

“Don’t be surprised if you get in a fatal car accident,” Rae answered, according to Michelle. He spoke very quietly, nearly in a whisper.

“What did you say?” asked Michelle.

“It was a joke,” Rae said.

“It’s not funny,” Michelle said.

“That’s why it didn’t work out,” he said. “You never know when I’m joking.”

Back in Charlotte one day, Rae got off the phone, turned to Amber, and said, as she recalls it, “Would it be messed up if I had somebody, you know, kill Michelle and my son? Or just my son, so that I wouldn’t have to pay her any money? Or if she just got in, like, a car accident, or something happened to her, I could have my son and I wouldn’t have to pay her money?”

He said it jokingly. Amber had overheard him talking about the same thing to a friend. Yeah, she said. It’d be messed up, Rae.

So some months later, when Amber called from Boulder to say she was pregnant after her five-day visit and Rae insisted she get an abortion, insisted he was not going to have any more kids by women he had no intention of being with, well, how could Amber be surprised when he said what he said to her?

“Don’t make me send someone out there to kill you,” Amber remembers him saying. “You know I would.”

This one didn’t sound funny at all. She had the abortion. Barbara Turner hadn’t raised her daughter to be no fool.

Cherica Adams worked in the Men’s Club boutique. She also danced under an alias at a different bar—over on the stages of the Diamond Club, a slightly more frayed entry in the topless-club genre, a place where a dancer is likely to be visiting from her home club in Buffalo for the long weekend, to pick up a couple of bucks, leaving the two-year-old back with her grandmother. Cherica Adams was a very attractive, baby-faced young woman who moved with a glittery crowd and felt equally at home backstage at a Master P concert or courtside at the 1998 NBA All-Star Game in Madison Square Garden, where several players, including Shaquille O’Neal, came by to say hello to her.

They never really dated, Rae and Cherica. They had sex a few times. Rae was also having sex with an exotic dancer who was having an affair with Charles Shackleford, a former Charlotte Hornet who happened to be married with three children, but it was Cherica whom Rae got pregnant, in March 1999—exactly one year after he and Amber conceived their second child.

Frequently injured, no longer a starter, Rae had by now become that singularly sorry football phenomenon: a first-round draft pick gone bust.

Rae was ambivalent about this one. On the one hand, he kept a new set of baby furniture in a storage facility under his name and took Cherica to Lamaze classes. On the other hand, it was at a Lamaze class that Rae first learned Cherica’s last name.

Rae’s second season had been a disappointment. He’d broken his foot after a forty-seven-yard catch, and he’d missed most of the year. When Cherica got pregnant, his world began to close in.

He was taking grief from teammates and friends about letting a stripper use him, about her boasting all over town that she was carrying Rae Carruth’s baby and wasn’t going to have to work anymore. By now Rae’s circle of male friends had expanded. Tired of the slick jocks in the Panthers’ locker room, he was glad to finally meet some people who were real. This new coterie included a man named Michael Kennedy, who had dealt crack, and a man named Van Brett Watkins, who had once set a man on fire in the joint and stabbed his own brother. Watkins, too, had unusual ways of showing love to his women. He’d once held a meat cleaver to his wife’s face.

Frequently injured, no longer a starter, Rae had by now become that singularly sorry football phenomenon: a first-round draft pick gone bust. Taxes and agents had taken half the bonus. He’d invested in a car-title-loan scam that had promised the trappings of easy money—and lost his money. He’d hired former wide receiver Tank Black, later indicted on fraud charges, to manage his money. He’d signed a contract on a new house, but he’d had to pull out when he couldn’t get the financing, and the owners had sued him.

And he had hired Van Brett Watkins, for $3,000, to beat up Cherica Adams so she’d lose the baby, but Watkins hadn’t delivered.

He was tired of being victimized, tired of having these women sucking out his sperm, tired of being rewarded for all his kindness by predators and gold diggers. Tired of taking the ragging. Panicked at the money situation.

So Rae did the only thing he could do, the only option they’d left him.

It’s as dark as Charlotte gets, the two-lane stretch of Rea Road a few miles north of the movie theater where Cherica and Rae went that night, in separate cars, and it’s so silent, so still in the hour after midnight on a weekday, that if you stop your car in the dip in the road and kill the engine, you can imagine yourself back in the South when the farmland was creased by rambling stone walls and the woods were thick with kudzu.

There are houses here, a few of them, a light or two winking through the trees, but none has a clear sight line to the spot. No one could have known the exact location, even if anyone had been looking, even if someone had been awake and heard the hush of tires on pavement down the road.

No one could have seen Rae’s Ford Expedition slowing down in front of Cherica’s BMW, blocking her path. No one could have seen Michael Kennedy’s rented Nissan Maxima pulling up alongside Cherica.

But they’d have heard the five distinct cracks of the .38, when Watkins sent five metal-jacketed bullets through the tinted glass of the driver’s window of the BMW. Four of them hit their target, burrowing through Cherica Adams’s lung, bowel, stomach, pancreas, diaphragm, liver, and neck, one of them passing within an inch of her fetus, leaving behind two distinct clusters of star bursts in the glass.

They’d have heard Rae’s car pull forward and disappear up Rea Road, and Kennedy making a U-turn to go the other way, and Cherica’s BMW weaving down a side street until it crawled to a stop on someone’s lawn and she bled out her life onto the front seat. They’d have heard the moans. They did hear the moans, in fact; the woman who lives in the house where Cherica ended up that night told me she’d never forget the moans. But she wouldn’t give me her name, and she wouldn’t open the door more than a few inches, just far enough to flick out her cigarette ashes.

But she did remember one more thing: how after Cherica repeated Rae’s license-plate number to the 911 operator, after she pleaded with the operator to save her life, Cherica had had the presence of mind to carefully place the cell phone back on the dashboard.

One other detail of the scene escaped the woman’s notice. The way Rae looked back at Watkins, the shooter, in his rearview mirror. As Watkins remembered it, for the briefest moment, their eyes met.

They found him lying in the coffin-dark trunk of a gray ’97 Toyota Camry in the parking lot of a $36-a-night motel in Tennessee, surrounded by candy bars and two water bottles filled with urine and a cell phone and a couple thousand in cash.

Cherica was conscious when the ambulance arrived at the hospital. Unable to speak, she motioned for a notepad and described the way Rae slowed down in front of her. “He was driving in front of me,” she wrote. “He stopped in the road. He blocked the front.”

Cherica gave birth to a son named Chancellor, who survived. Then the mother went into a coma from which she never awoke.

Nine days later, at dawn on Thanksgiving, police investigators drove to Rae’s house in the Ellington Park subdivision. They rang the doorbell. Rae came to the door naked. A woman was in the bedroom. They arrested him. He made bail. Three weeks later, when Cherica died, and Rae now faced first-degree-murder charges, he skipped town.

They found him lying in the coffin-dark trunk of a gray ’97 Toyota Camry in the parking lot of a $36-a-night motel in Tennessee, surrounded by candy bars and two water bottles filled with urine and a cell phone and a couple thousand in cash. His mom had turned him in: Theodry had given him up to the bail bondsman. When FBI agents popped the trunk, Rae kept his eyes closed, and he didn’t move.

Soon he opened his eyes, raised his hands, and climbed out. This seemed curious at the time, but it doesn’t seem curious anymore. Knowing Rae as we do now, we know that he simply reasoned thusly: if he didn’t see them, then the agents weren’t there at all.

Michelle Wright watched the trial on television, watched as Candace, Starlita, Dawnyle, Monique, Fonda, and Amber took the stand, and told Little Rae about all the pretty women.

“How many girlfriends did my dad have?” Little Rae asked his mother.

“I don’t know, Rae,” she answered. “I’m learning just like you.”

“But you can’t marry that many women, can you?”

“No,” said Michelle. “You can’t.”

The creak of the knee braces Rae wore beneath his pants to keep him from fleeing was the only sound in the courtroom when he was led in to hear the verdicts, one day shy of his twenty-seventh birthday. Out the smoked windows in the back of the courtroom, black clouds huddled on command and great Gothic spills of water tumbled out of the Southern sky as Judge Charles Lamm pronounced the verdict of a jury of Rae’s peers: guilty of three of four counts, including conspiracy to commit murder. Innocent of first-degree murder.

The weeping of the women on Cherica Adams’s side of the courtroom was immediate and audible and joyous. In a state with no parole, a murder-conspiracy conviction means that Rae will be off the streets for decades. He’ll serve nineteen years minimum, twenty-four maximum.

Rae took the news of the verdict the way he’d taken everything for seven straight weeks: with no discernible emotion or expression. Just, as the bailiff led him for the last time past his women, a slight nod—at Tnisha, whose expression was confused, and at Theodry, who was already steeling herself to be strong, and at the rest of the women, who were looking toward him with whatever expressions they could muster.

Rae seemed, if anything, distracted, as if it had just occurred to him for the first time: the only intimate adulation he’d get for the next quarter century would be from men. The women were finally out of his life.

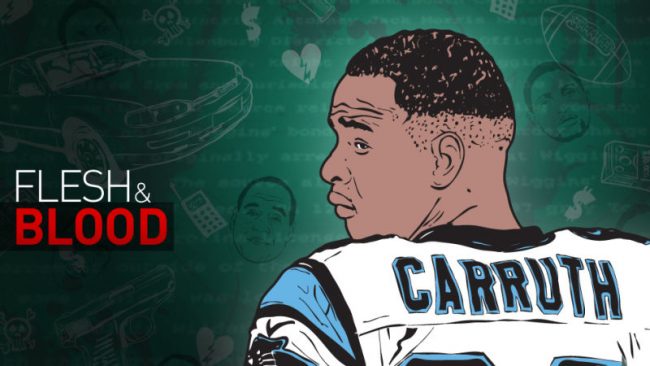

[Illustration by Sam Woolley]