Last year, 1,806 women in America had AIDS, 794 of them were from New York City. Most of us may not yet be aware of this grim new reality, but it is becoming increasingly pervasive. Today, AIDS sufferers are no longer exclusively the gay men and male intravenous drug users who first bore signs of the disease. They’re wives, sisters, mothers—even children, AIDS has become the biggest killer of women in their twenties, and doctors predict it could become the greatest killer of women in their childbearing years. Women infected with AIDS run the risk of passing it on to their babies in utero, or during childbirth. In the New York area, 141 children have been diagnosed with AIDS (71 percent of them have died), and hundreds more could be carrying the virus. Most of them will die before the age of three.

“Women are now where the gay community was in 1981,” says Dr. Dooley Worth, a community health planner who works on the Lower East Side. “We must make women aware of the dangers so we can head off this epidemic before it takes the same devastating toll on us too.”

The appearance of women and children among the dramatis personae of this relentless tragedy has altered the traditional profile of the AIDS victim. While the typical male patient is white, middle-class, and homosexual, most women in New York suffering from the disease are black (51 percent) or Hispanic (36 percent), poor, and heterosexual. Most have contracted the disease through their own drug use (past or ongoing), but a growing number of women are getting it through sexual contact with a former or current user, or through sex with a bisexual man. In the past year, there has been an 81 percent increase in female AIDS cases in New York City as a direct result of heterosexual transmission, making this the fastest growing disease category for women, and not only for poor minority women: “We’re seeing plenty of white, middle-class women becoming infected with the AIDS virus, too,” says Dr. Worth. Any woman who participates in “risk behavior”—such as having multiple sex partners who don’t or won’t use condoms, or having a partner who’s bisexual—is at risk of catching this disease.

“Obviously, middle-class women are sexually active, too,” says Dr. Worth. “The tragedy is that, because of how the disease has been reported, most of these women didn’t even know that they are at risk.” Compounding the tragedy is the fact that women tend to die of AIDS even faster then men do.

The big question is: Why didn’t most women know their risks, when the medical profession has known for at least four years that women were able to contract AIDS through heterosexual sex? For one thing, transmission of the virus through vaginal intercourse was not even cited as a risk factor by the New York State Department of Health until October 24,1985. Although the U.S. Public Health Service has issued warnings about vaginal transmission since 1983, U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop made his first major statement only last October. And although Koop plainly stated that heterosexual transmission is expected to increase in the future, many health agencies are still describing AIDS as a selective killer, confined to certain “risk groups” such as gay men and IV drug users.

Most professional, middle-class Manhattanites find it easy to turn their backs on the disease. But its encroachment into the center of the metropolitan area will soon make that impossible.

“Attaching it to the behavior of these so-called risk groups has enabled the disease to be packed off onto the fringes of society, so clean-living, upstanding Americans could reassure themselves they wouldn’t fall prey to it,” says one health worker. Despite the widening categories of victims, a disturbingly high percentage of the general public still believes that it is safe.

Most professional, middle-class Manhattanites find it easy to turn their backs on the disease. But its encroachment into the center of the metropolitan area will soon make that impossible. The New York City Health Department projects that there will be 40,000 victims of AIDS in the city by 1991, a growing number of them women and children, a growing number of them middle-class. Among women, the highest risk group may be those women who have multiple sex partners or are the wives of bisexual men. But even women in monogamous relationships with heterosexual men are not safe. Thirty-year-old Mary Brown* was put at risk before she even knew she could be. Nothing about her lifestyle made her even consider the possibility of getting AIDS. Brought up by religious, working-class Puerto Rican parents in downtown Manhattan, Mary was the kind of girl who “did everything right. I ate all the right foods, I did lots of exercise, I didn’t take drugs, I didn’t drink, and I’d been faithful to my boyfriend for the past two years.”

But Mary’s boyfriend was a former IV drug user who had become hooked while serving in Vietnam. He had stopped five years before she met him, but by that time it was already too late.

When he took a blood test to see if he might be infected with the AIDS virus (now known as the HIV virus), he discovered that indeed he was. Although he was healthy and had no early symptoms (known as ARC, or AIDS Related Complex), he learned that testing ‘seropositive’ to the virus meant that he was nevertheless capable of infecting a sexual partner. In shock, Mary took a test, too. And in the two weeks before her results came back, she confronted her own mortality.

“I thought, Obviously, I’ll be positive, too, and that means I’m going to die’.” she said. “I thought, I’m thirty years old, and I’ll never have a baby.”

Mary’s boyfriend was so distressed by his own condition that he moved out of their apartment. “He said, ‘I’m a Ieper, and I can’t stay to watch what will happen now that I’ve given you this terrible disease.’” Mary recalled. “So he left, and I felt totally abandoned. But I couldn’t tell anyone what was going on. My biggest concern was how to keep the truth from my family. I decided they should never know and that before I got really sick and they discovered the truth, I would kill myself.”

For many Hispanic families, like Mary’s, and many black families, the specter of AIDS carries overwhelming cultural, as well as physical, implications. “In a Puerto Rican or black community, the connection with homosexuality makes AIDS quite unacceptable,” explains a health worker who grew up in the melting pot of the Lower East Side. “These communities only produce macho men and Madonna women. Macho men and Madonna women don’t get ‘bad’ diseases like AIDS.”

So women like Mary tend to keep their “bad” diseases secret, not just for their own, but for their family’s, sake. Many hide it mainly for the sake of their children.

“They are most frightened of inviting discrimination onto their children and making them pariahs,” says Dr. Joyce Wallace, director of the Foundation for Research on Sexually Transmitted Diseases on West Twelfth Street. “As long as they can, they put every remaining ounce of energy into keeping up the illusion that they’re normal and into trying to bring whatever comfort they can to their children.”

It’s ironic that most of these women tend to live in tight-knit communities among large extended families. Ironic because they, far more than their male counterparts—who often live alone or with a lover, and in a city far removed from their families—bear the burden of their disease in isolation. Middle-class women are similarly isolated. “They have no more support systems—except, perhaps, individual therapy—than lower-class women do,” says Dr. Worth. “In a way, if they’re professionals, they have even more to lose.”

As they become sicker, women with AIDS simply disappear, according to Wallace. They burrow deeper and deeper into an enveloping underground where they hide, hoping to die with dignity—an opportunity too often denied them.

Meanwhile, many bisexual men, including macho types, work to keep up the illusion of their own heterosexuality, frightened to admit what they practice in secret. Human-sexuality researchers estimate that three million men in America are either bisexual or have experimented with homosexuality at some stage in their lives.

“And their wives may be more at risk than most women,” says Aurele Samuels, a researcher who, with Dr. Dorothea Hays, an associate professor at Adelphi University, has completed some unique research into issues affecting the wives of bisexual men. “The more covert their husband’s activity, the more anonymous it is likely to be. And the more he may be experimenting to establish his orientation, the more promiscuous he’s likely to be.”

Samuels is outraged that public health officials have not voiced concern for the unwitting wives of bisexual men. “The problem is, there is simply no accurate education about the full spectrum of sexuality,” she says. “We’ve been dodging this issue for decades, and now women are going to have to do something about it, because men aren’t going to go near it.”

No one, according to those working with AIDS, is prepared to go near the subject that lies at the very heart of this public health crisis—sex. “No government agency, not on the city level, the state level, nor in Washington, dares to touch the really explicit stuff that has to be talked about in connection with AIDS,” says one health worker.

Indeed, real assessment of AIDS risk does get explicit: it demands talk of orifices, of body fluids, of deviant sexual practices, of men visiting prostitutes, and of the number of partners—of both or either sex—needed to satisfy certain carnal appetites. In today’s reactionary America, these are not easy topics of conversation.

“The Catholics balk at the prospect of widespread contraceptive use; the blacks and Hispanics totally reject the notion of homosexuality and bisexuality in their cultures; and many women, especially in minority groups, find it next to impossible to stand up to their lovers to demand that they wear rubbers,” says another health worker. This sensitivity to the issue has kept the subject off the campaign trail as well. “No politician is willing to go near these issues—some aspect offends virtually every cultural group in this country,” says the health worker. Even the Surgeon General acknowledges that “many people, especially our youth, are not receiving information that is vital to their future health and well-being because of our reticence in dealing with the subjects of sex, sexual practice, and homosexuality.” He adds emphatically, “The silence must end.” But when? Even in the light of this strong admission of widespread heterosexual risk, we still do not get public health warnings on TV and radio or even billboards.

Piercing the homophobia and sexism of the black and Hispanic cultures is just one of the problems that community spokespeople such as Dr. Benny Prim, executive director of the Addiction Research and Treatment Corporation in Brooklyn, and Ruth Rodriguez of the Hispanic AIDS Forum are wrestling with, in what they say is a lonely battle. Both feel that the special needs of their communities, overlooked at the best of times, are being especially ignored now.

“The Hispanic public need to get their information from their own community leaders. It’s not enough just to translate things into Spanish. That never got information across, even with noncontroversial health issues like vaccinations for childhood diseases. So why should anyone believe they’re getting the information across now!” says Rodriguez.

“What’s now being done about drugs will be done about AIDS. But now there’s just nowhere near enough. I don’t know whether it’s intentional racism or not. I pray it’s happening by accident.”

An emotional Dr. Prim expresses the similar frustrations he feels within his own community.

“I do think the black community is being shortchanged over this epidemic,” he says. “There’s not enough information in the neighborhoods where it’s needed, like Harlem; and the inertia of the state and city is incredible. I have to say something because my people are dying, and these officials are supposed to be helping to keep them alive. You wait for a year or so, until AIDS really hits the majority community, and you’ll see a blitz of public information out there.

“What’s now being done about drugs will be done about AIDS. But now there’s just nowhere near enough. I don’t know whether it’s intentional racism or not. I pray it’s happening by accident.”

Meanwhile, AIDS is taking its heaviest toll in black and Hispanic neighborhoods. In Brooklyn, in the Bronx, in Harlem, and on the Lower East Side, AIDS has left indelible marks on communities that already bear the unsightly scars of myriad other social ills: drug abuse, alcoholism, homelessness, abject poverty.

“The building blocks for the epidemic of AIDS have to be seen in a sociological perspective,” says Monnie Callan, CSW, a social worker who works with AIDS patients at the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx. “When people live in burnt-out buildings and shells full of rubble, and when mothers never undress their kids at night in case they have to grab them to escape a fire, well, of course they end up on drugs. Anyone would do something to blank out all that horror and hopelessness.”

Public health officials—though ill-equipped to control social ills that contribute to drug use—vigorously defend their efforts in combating AIDS. A spokesman for the City Department of Health, Marvin Bogner, finds the accusations of inertia “absolutely preposterous.”

“We have been spending millions on health education and information programs; we have doubled and redoubled our efforts to inform the public of the risks,” he says. “And the fact that outbreaks of AIDS among the largest at-risk category have been decreasing is, I’d say, an indication of an effective public-information program.”

“We see kids whose mothers bring them into the emergency room and then say they’re going out for a cigarette—and never come back.”

The greatest problem in terms of disseminating information, he says, is how to reach the drug-using community, which is diffuse and often unreceptive to education. At the New York State Department of Health, Frances Tarlton, associate director of public affairs, pinpoints another problem confronting public educators: the need to outline the risks without causing mass hysteria. “Our dilemma is how to get to those at risk without unnecessarily scaring those who aren’t,” she says.

It is doubtful, of course, whether any group in America is totally without risk. Dr. Neal Steigbigel, head of the division of infectious diseases at the Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, insists that “theoretically, the population at risk is the entire world.” Certainly, the risk confronting the heterosexual community of a large city such as New York is no longer theoretical. “The question is, that with an incubation period of up to ten years, how can you be really sure about the history of your sexual partners?” asks Dr. Worth. The answer is, you can’t.

It is certainly true that scaring the public can give rise to extreme exhibitions of discrimination and hysterical demands for draconian changes in social and health policies. Moves have already been made to have HIV-carriers sacked from their jobs, to have individuals in certain risk groups exempted from their rights to medical and life insurance, and to deny gay fathers access to their children. Just a step away from this is the call to have HIV-positive mothers removed from their children—or prevented from having children at all.

Since babies of seropositive mothers are likely to be born with the virus themselves, the dilemma of whether these women should bear children is one of the toughest ethical questions to emerge from the quagmire of issues raised by AIDS. It’s a dilemma that thirty-two-year-old Roz Harvey* had to confront when, shortly after celebrating her first anniversary off drugs, she discovered she was pregnant. Roz, who had been a drug user for many years, already had two children, then ten and twelve. Some months after she had kicked her habit, she had agreed to have her blood tested for HIV, as part of a study being carried out on AIDS and its connection with former drug users. She had never bothered to find out the results, but now that she was pregnant, she decided she had to know. She discovered that she had tested HIV-positive, and she felt forced to make a decision about whether to proceed with her pregnancy.

The decision was agonizing for her boyfriend, Jamie, as well as for her. “Jamie was in so much pain, he’d just look at me and his eyes would tear up,” she says. She talked to doctors, to genetic counselors, to the AIDS Hot Line, and finally to the Women and AIDS Discussion Group at the Stuyvesant Polyclinic on the Lower East Side. Finally, she decided to have an abortion.

“I couldn’t see bringing a child into the world, not knowing if I’d have to stand by and watch that baby die,” Roz said. “Plus, I was told that the trauma of childbirth could trigger off my own symptoms. I thought, What would happen then? Would the two of us die while my other two kids stand by and watch? I knew I couldn’t do that.”

Today, an increasing number of AIDS health workers are encouraging women in Roz’s position to make similar decisions. In Brooklyn, Dr. Prim and Barbara Gibson, director of an AIDS community-education program, counsel their HIV-positive clients to consider abortion and sterilization. The Albert Einstein Medical Center in the Bronx has also begun special “pregnancy prevention counseling” for seropositive women. While these kinds of services have their critics (“Why not tie up men’s penises?” asks Monnie Callan), it is the doctors at hospitals such as Einstein who have to deal with the tragedy of babies whose mothers are either dying or dead from AIDS, or who are too frightened or too sick to look after them.

“We see kids whose mothers bring them into the emergency room and then say they’re going out for a cigarette—and never come back,” says Dr. Brian Novick, assistant clinical professor of pediatrics at Einstein. There, and in the wards of municipal hospitals all over the city, newborn babies and young children have been abandoned, with little hope of adoption or foster care.

In the past five years, between 500 and 700 babies have been born to seropositive women in New York City. There have been 141 children diagnosed with AIDS, and 101 of them are already dead. Doctors believe that by next year the number of pediatric cases will have doubled.

Children have become the final, and neediest, victims of this heartbreaking epidemic, caught in the ultimate no-win situation. If they are born with the virus, they may get sick and die. And even if they don’t develop symptoms, they are still shunned by their terrified communities and left to the care of institutions.

Recently, a new component has entered into the picture to compound the predicament of these children, according to Dr. Margaret Heagarty, director of pediatrics at Harlem Hospital, where there are currently some six to ten children afflicted with AIDS or ARC. “The system is beginning to equate any form of drug abuse with the potential for AIDS,” Heagarty says. “So a lot of kids whose parents are known to be, or thought to be, drug users—even crack users—are having trouble finding foster-care placements.”

At present, Harlem Hospital has between twenty and thirty newborns in this situation, awaiting placement. “And projections are that it will get worse,” Heagarty says. Yet, to date, there are very few services designed to help women and children AIDS victims. They feel alone, and their isolation is compounded by poverty and political powerlessness. As drug users, as members of minorities, and as women, they are, on the whole, less well equipped to fight for the kind of services that the gay community has so successfully marshaled for itself over the past few years. As yet, there is no citywide equivalent of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the service that so successfully deals with that constituency’s needs. And although GMHC has tried to cope with the growing number of different patients now needing care, many low-income women are unwilling to take their problems to counselors who are, by and large, middle-class, white, and male.

Increasingly, services are springing up to fill the need—many run by women. One of them, the women’s group at the Stuyvesant Polyclinic, is where both Mary Brown and Roz Harvey found counseling and comfort for their particular dilemmas.

At any one time, the group is composed of about a dozen women who consider themselves vulnerable to the AIDS virus, either through having shared needles or through sex with a high-risk partner. All are at various points along the seropositive tightrope—some fear they may test positive, some already have ARC (they are carrying the virus and have some early symptoms of AIDS, such as swollen glands, lack of energy, unexplained fevers, heavy night sweats, and weight loss). They meet weekly in circumstances of strict confidentiality to discuss their situations and to get advice and information about the alternatives available to them.

“The most important thing about this group is that it has given women a place of their own to talk to other women, to let off steam, and to find some support and solidarity,” says Dr. Worth, who started the group last August. “It’s wonderful to see how powerful women can be when they get together.”

“The women in the group are absolutely the only people in the world who know what’s been going on with me,” says Mary Brown. “And they took the burden of that terrible secret knowledge off my back. When I first walked into a meeting, I arrived feeling already stigmatized. I thought, Here’s this little group of outcasts, and we can only talk to each other because we’re the only ones in the world who know what this feels like. But it wasn’t like that—it was terrific. In a sense, it totally changed my life.”

The women suffering from full-blown AIDS have many urgent needs—from community services and home-support networks to help them stay out of the hospital for as long as possible, to lawyers to help them draw up their wills and make custody arrangements for their children. At Montefiore, Monnie Callan (with her colleague Lauren Gordon) has started a support group for the families of AIDS patients, the only one of its kind in the Bronx. “Both Lauren and I have a caseload of some fifty to sixty patients, whom we try to care for both in and out of the hospital, but for each patient there are at least four or five more people—their families—who also need our help,” Callan explains. “Right now, Lauren and I are drowning.”

Most AIDS workers are. The disease will consume as much time as they let it. Many find it hard to leave work before 10 P.M., and often they take their frustrations and sadness home with them. These women are driven, dedicated, and immensely courageous. AIDS has presented them all with a deadly challenge and all seem determined to meet it, blow for blow, as it extends its shadow across the city. “It has taken over my life—and almost everyone I know who works with it,” admits Dr. Dooley Worth.

Most people continue to believe that responsibility for curbing the spread of AIDS lies with the scientists, that the real fight against AIDS is taking place in the nation’s laboratories, and that ultimately it will be miracle drugs and cures that will wipe out this disease once and for all.

Dr. Joyce Wallace has made a conscious decision not to let AIDS totally overtake her life, or so she says. But after a day of seeing patients, she stays at her desk until late at night writing up her research and poring over the medical literature piled high around her. But she still sees patients not suffering from the disease, and she is determined to keep up other areas of interest. She recently became a certified mohel, officially qualified to perform circumcisions on newborn baby boys. “That way,” she says, “every once in a while I can join a party and celebrate life.”

In whatever way they can, the field-workers try to emphasize the positive. And one positive note providing encouragement to those working with AIDS is the prospect of public education. “So much can be done in the field of prevention,” says Karen Solomon, assistant director of the AIDS Hot Line, which currently answers some 200 to 400 calls every day. “Every one of us can be an educator. That’s what makes this work so important,” Solomon concludes.

The gay community has shown that education about changing sexual habits and “safe sex” can be very effective: so much so that doctors all over the country have reported unprecedented drops in the number of gonorrhea cases they are treating among gay men. Now it’s women’s turn to be educated, and according to the experts, the need is great. The stumbling block is women’s own denial, they say. “Women just don’t want to believe they’re at risk,” explains Dr. Worth. “And part of the denial is to say ‘not me—them.’ Women, especially middle-class women, are having a hard time accepting that it can happen to them.”

“Women tend to think that if you love someone you have to trust them,” adds Karen Solomon. “But unfortunately, the AIDS virus doesn’t stay away from women who are loving and trusting.”

So no matter how busy, or how overloaded these doctors and health workers are, all put aside hours of their valuable time to address conferences and forums, to be interviewed by journalists, and to appear on TV—to get the message across that AIDS is a sexually transmitted disease that is spreading beyond the boundaries of the so-called “risk groups,” and can only be halted if every single woman takes responsibility for her own health and sexual behavior.

“We have got to make condom a household word and tell every woman that today, if you want to be sexually active, you do not go out of the house without one,” says Dr. Wallace. (There is also evidence that the spermicide Nonoxynol-9 used with a condom is effective in killing the virus.)

“Women have got to accept responsibility for their own sexuality and not turn it over to men,” adds Barbara Gibson, director of executive affairs at the Urban Resource Institute in Brooklyn.

Most people continue to believe that responsibility for curbing the spread of AIDS lies with the scientists, that the real fight against AIDS is taking place in the nation’s laboratories, and that ultimately it will be miracle drugs and cures that will wipe out this disease once and for all. But struggles of equal proportion are taking place all over the city, in its very social fabric, to try to change the conditions that enable the epidemic to spread. And these struggles have historical precedents: many diseases, such as cholera and tuberculosis, that were killers in their day have been more or less eradicated from our society not through medical means but by public health measures, much like the ones being advocated to prevent the spread of AIDS today. AIDS can be curbed, say the experts, so long as people—all people and not just those in the so-called risk groups—realize that they, too, have a part to play.

“As women, we all have to be strong enough to make a considered choice about our sexual partners, rather than let responsibility go just to have a man for a few moments,” says Gibson. “Sometimes, that’s a hard choice to make. For some women, being held is worth a pot of gold.”

Today, we must all consider: Is it worth a life?

*The names designated with an asterisk have been changed at the women’s request.

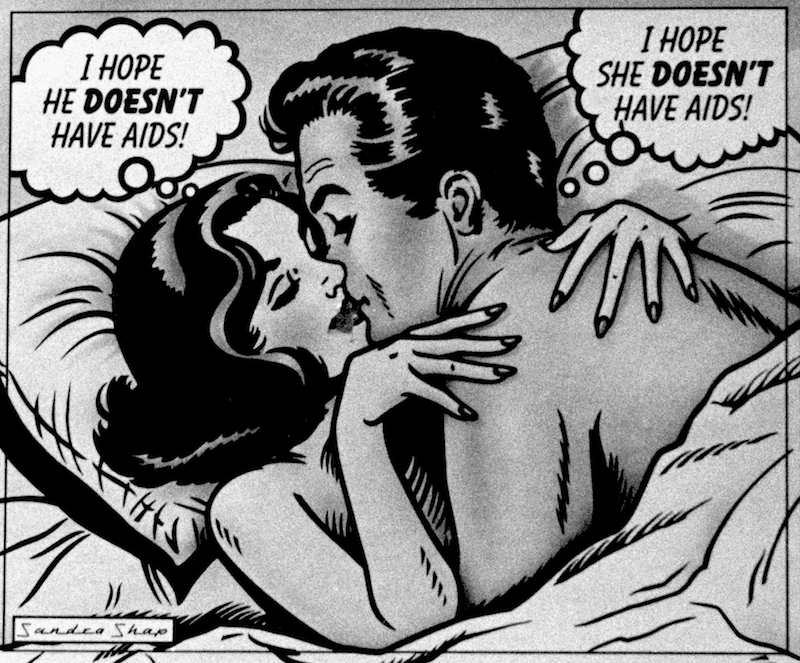

[Featured Illustration: Sandra Shap]