There were four old ladies sitting in the lobby of the Fifth Avenue Hotel. They were four of the oldest ladies to be found anywhere. They sat facing one another in a quartet of lackluster wing chairs, holding themselves as motionless as a photograph. Across the lobby, a whey-faced man in a colorfully stained overcoat and an Army hat read loudly from a racing form for the obvious benefit of a young hatcheck girl who chewed gum and said nothing.

One of the old ladies had a garishly painted scarf tied sportily around her neck. Her mouth was lost in an enormous circle of red lipstick and her cheeks were made up to the color of a runner peach. She fingered the tip of her scarf lightly, as if it were a corsage.

“This scarf…” she said suddenly. She stopped, out of breath, as if she had just run a great distance. One of the other ladies turned her head and looked away.

“Mary gave me this scarf,” the lady with the red mouth declared. She tightened her grip on the scarf and slapped it at her three companions. “I think it’s quite lovely, really.”

Another one of the ladies leaned forward and examined the scarf with interest. Her eyes swam around behind a pair of thick-lensed spectacles like tropical fish in an aquarium. She reached out a bony hand and nudged the lady sitting beside her, who gave her the appearance of being dead.

“Mary,” the lady with the fish eyes said, “Alice is speaking to you.”

Mary awoke with a start, as if there had been a loud explosion. The lady with the aquarium spectacles pointed gently to Alice who was waving her scarf gaily in their direction.

“A lovely scarf,” Alice repeated, “in my opinion.”

Mary stared in terror at the lady with the lipstick mouth. Her hands tightened around the arm of her chair as if she were floating away. Her mouth began to tremble and open slowly, like a monster coming to life. A thin thread of saliva ran unheralded down her chin.

“Filth,” she cried loudly. “Nothing but!”

Her words were drowned out immediately by the high-pitched sound of a radio turned to full volume. The music swept through the lobby like the heralding of trumpets, bringing with it an exuberant crowd of people executing an impressive Fellini-like costumed entrance.

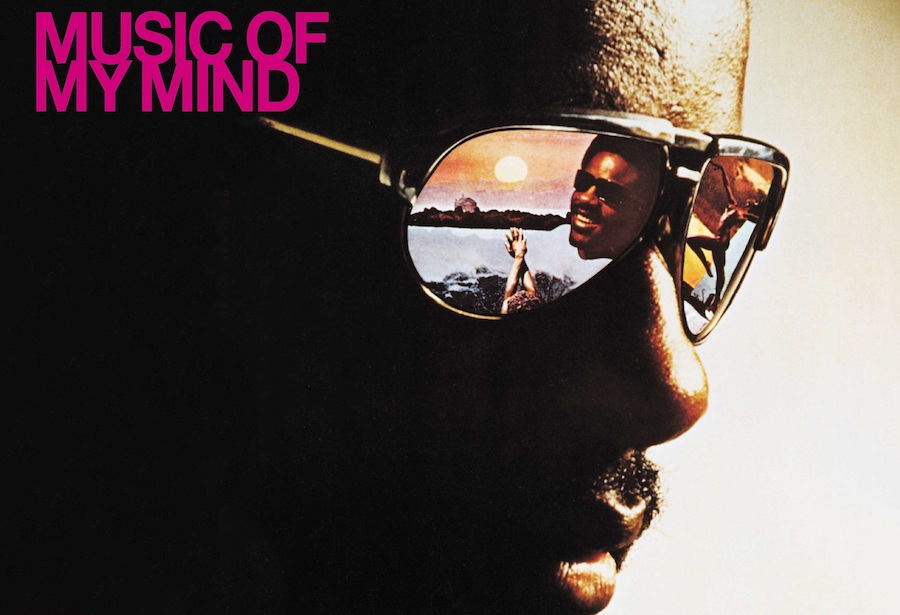

Leading the pack was Stevie Wonder, wearing a pair of wire-framed aviator sunglasses and a black leather outfit intricately splattered with metal studding. He had a matching cap that he wore cocked smartly to one side, Dead End Kid-style. His head bobbed about freely on top of his tall, erect body, as if it were on a broken spring.

Stevie’s brother Calvin held his left elbow lightly, moving him through the lobby to the elevators. Pulling up alongside in a semi jog was a heavyset black man wearing the bluest of all possible blue track suits with snazzy red and white piping running everywhere, a pair of white Adidas sneakers and a terrycloth tennis cap. He carried a combination radio-and-cassette player which he held up to his hear and listened to intently every now and then, as if he were about to receive instructions from headquarters.

Following at close quarters was the rest of the entourage, several men with leather coats and embroidered briefcases and a sprinkling of ladies, some breathtakingly beautiful, others surprisingly unremarkable. Trailing the group was Ira Tucker, Stevie Wonder’s general factotum. Tucker studied the lobby from behind a pair of lightly tinted heart-shaped glasses, apparently finding nothing of interest in what he saw.

“Steve,” a man’s voice boomed. “What’s your hurry?”

Stevie stopped moving, tossing aside his head to one side, pulling Calvin slightly off balance. Everybody else wound down to a halt.

“Hey, Pat!” Stevie called out in a small shout. “Where you at?”

Pat came over and took Stevie by the hand. He was the manager of Feathers, the bar and restaurant of the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Pat was a stocky, full-faced man who has a museum of New York reflexes. The waistband of his trousers rode low on his bulky frame.

“So,” Pat said, still holding on to Stevie’s hand, “you’re back to do the Garden?”

“Tomorrow night,” Stevie said. His head wandered over to one side until his chin was almost touching his shoulder.

“That makes two shows in New York on the same tour,” Pat said, “that’s big stuff.”

“The first gig was on Long Island,” Ira Tucker said. “Uniondale, someplace way out. An entirely different part of the country.”

“The Garden is the big one,” Pat told them.

“It should be,” Stevie said, “a beautiful thing.”

“Then what? Back to the coast?”

‘Well, it looks as though we might be going to Japan,” Stevie said. “Maybe Australia, New Zealand…”

“New Zealand,” Pat said. He looked around and beamed at everybody. “You folks are too crazy for New Zealand!”

“New Zealand’s supposed to be very cool,” Tucker said. “My sister did a tour in New Zealand. She said New Zealand was funky.”

“If it not cool,” Calvin stated, “it will be cool when we arrive.”

“Maybe there are a lot of women down there,” Pat said, “Who knows?”

“Now you understand, of course,” Stevie said, pulling himself so close to Pat’s face that he was practically whispering in his ear, “I don’t go in for that sort of thing at this point.”

“So then,” Pat said at length, “it was a good tour for you guys?”

“Pretty good,” Tucker said. “We made about 26 cities in something like 30 minutes.” He shrugged this off. “We did okay, though.”

“The people were beautiful,” Stevie said. “Everywhere we went.”

Pat clapped Stevie on the back and waved them off as he went back into the restaurant. “Come in for a drink later,” he called after them.

“I had a Tequila Sunrise in there today,” Calvin shouted back. “There was no tequila in it, man. It was all sunrise.”

“You’re too young for tequila,” Pat told him, but by this time they had all moved on through the lobby and were waiting for an elevator.

The four old ladies, who had been watching the entire exchange as if they were sitting center court, turned their heads and watched Stevie Wonder’s caravan trail away.

“Who was that?” the lady with the fish eyes asked.

“What?” Mary demanded in a shrill voice, nearly pulling herself out of her chair. “What is it?”

“I was asking,” the lady with the fish eyes said in a loud, patient tone, “who was that tall Negro man who was standing here?”

Her voice carried through the entire lobby. The hatcheck girl lifted her eyes momentarily and swung her hair lightly behind one ear.

“Too much noise,” Mary said to nobody at all. “To much dirt, wherever you are.”

“I’m not sure,” said Alice with the lipstick out, “but I thought I recognized the young man. I’ve seen his picture.” She tapped her forehead with one finger, a pantomime of thought. “I believe he’s an athlete of some sort,” she said at last. “A basketball player, unless I’m incorrect.”

The hotel room was a low-level still life; everything within it was tainted by its dreary karma. The flowered drapes hung lifelessly by the windows like flags on a muggy day. The faded wallpaper and the worn out carpeting were testimonials to the unglamorous appointments of the Fifth Avenue Hotel.

“This room is a mess!” Stevie said, walking from the bedroom into the living room. “It is a terrible, terrible state for a room to be in.”

“It is,” Ira Tucker agreed, “a mess.” He picked up a stray electrical cord from a chair, reflectively tossed it on the floor and sat down. “For a star of your magnitude, man,” he said, “you are a disappointment to us all.”

“It’s blind people,” Stevie said, standing thoughtfully in the middle of the room. “Blind people are messy.” He turned his head and faced Tucker with an innocent grin. “They are not to be blamed for their personal … uh … appearance.”

“What shit is that?” Tucker said. “Giving blind people a bad name.”

“Don’t mess with me, man,” Stevie said. “I’m a professional. A show business personality, you understand?”

“A legend in your own time,” Tucker added. “I get it.”

Stevie moved over to one side of the living rom, which was crowded with recording equipment. He ran his hand over the top of a table, gathering up patch cords; then he squatted in front of a portable console and began hooking things together.

“Yolanda!” he shouted. He flipped a switch and one of the speakers gave off an ominous wail. He flipped the switch off and backed away from the machine for a moment’s consideration. “Yolanda!” he shouted again, louder. He swung his head around so that one ear pointed toward the bedroom doorway. “Where are you hiding yourself?” He sang this last line, hitting a high note with the last syllable.

Yolanda, Stevie’s fiancée, appeared in the doorway, her arms folded across her chest. She was barefoot, dressed in a bathrobe, wearing curlers in her hair. “Yes,” she said.

“Uh, Yolanda” Stevie said, “Tucker and I were just having a little discussion as to the state of this room and we were talking, uh, specifically about how this place,” he gestured about him using one outflung arm, a spaghetti-work of patch of cords dangling from hand, “got to be such an incredible mess.”

Yolanda ran her eyes around the room. One wall was taken up with the recording equipment; odds and ends of related paraphernalia were scattered about on the floor. There was an upright electrical keyboard off to one side, forming a partial barricade to anybody wishing to enter the tiny kitchenette. There were a sofa and a coffee table, both strewn with tape cassettes and cords of various lengths. There was a large slot-car racing set unassembled in a cardboard box resting in one corner.

“Well,” Yolanda said finally. “I don’t see anything that’s exactly mine.”

“See!” Stevie said. “See what I said!” He executed a quick twirl for the benefit of nobody in particular. “Everybody picked on the blind man! The blind man is…messy!”

Yolanda sighed and went over to clear off the couch.

Stevie knelt down on the floor and began to work with his equipment again. There was a crackle of static from the speakers.

“You’ve got too much shit up in this room,” Tucker told him. “One of these days you’re going to be sitting here fooling around, saying, well now, let’s put this little wire into that little hole there … and then pow! you’ll blow this whole building and your ass with it up in smoke. Then we will truly have the electrified Stevie Wonder.”

“I told you,” Stevie said, “not to mess with me. Because I…” He moved his hand lightly over the front of the console, locating an input plug. “I am a…” He stuck one of the patches into the socket and the room shook with a violent blast of sound.

“Yeah, I know,” Tucker said as Stevie yanked the wire out. “You’re a professional.”

The doorbell rang and Yolanda went to answer it.

“Oh, no,” she said unhappily, “I look so awful today.”

She opened the door and two black men, one older than the other, came into the room. Tucker gave them a wave of recognition. The older man had come to talk to Stevie about doing a documentary film. He wore a rather conservative suit offset by a Rain Hood-green turtleneck sweater. A blazing gold sunburst hung around his neck on a chain.

The younger man was a writer for a back newspaper. He walked purposefully into the room, glancing all around him as if he expected to meet with something that would cause him displeasure.

Without rising, Tucker made the necessary introductions and the two men settled down on the couch. Yolanda disappeared into the bedroom, clutching at her robe: Stevie followed her and returned holding a large portable radio.

“Take a look at this, man,” he said, handing the radio over to Tucker. “I just bought this thing today but it doesn’t work right. I think I should take it back.”

Tucker turned the radio over in his hands and examined it with the closest attention.

“What doesn’t it do,” he asked, “that it ought to do?”

“I can’t get police calls,” Stevie told him. He stretched out his arm until he located the radio in Tucker’s lap. “I can get everything,” he said, “except the police calls.”

He stroked the top of the radio with the tips of his fingers, as if he were petting a car.

“Cost me $500,” he told everybody.

“Five hundred dollars?” Ticker shouted. “For a radio?”

“Well, see, it’s not just … uh … an ordinary radio, you understand.”

Stevie reached around in back of him and his hand closed over the arm of a chair. He backed up slowly and sat down.

“See, the thing is,” he said, “with this radio you can get shit from all over the world. You can get Europe and everyplace. But no police calls.”

“Man, Steve,” Tucker said, “you are incredible. I mean you are really out there. What do you want the police calls for anyway?”

“It’s not so much wanting them,” Stevie said, “as not being able to get them. You know?”

“I can dig it,” the young black newspaperman said suddenly. Nobody paid attention to him.

“Otherwise,” Stevie went on, “the radio works real good. This afternoon I was listening to Dutch Top 40. Shoo bop, dee doo bop bah…”

“Dutch Top 40,” Tucker said. “Outasight. Were you on it?”

“Well, I don’t know actually whether I was or not,” Stevie said. “See, I was only tuned in for the top numbers…”

“Oh, yeah,” Tucker said, “I dig it. You were only tuned in for the top numbers. And are you telling me, Steve, that you were not among the top numbers? Say that just ain’t so, man.”

“Yeah,” Stevie said philosophically. “I guess their playlist is coming from a slightly different direction. Number One song was … uh … ‘Willie and the Hand Jive.’ ”

“‘Willie and the Hand Jive?’” Tucker said. “Isn’t that a golden oldie?”

“No, this is the new thing, Eric Clapton.”

“Rip-off reggae shit,” the newspaperman muttered with disgust.

“Eric Clapton loves your ass,” Tucker told Stevie.

“Yeah?” he said, looking pleased.

“White folks have always ripped off black people’s shit,” the newspaperman said, his voice rising. “Just asking the Rolling Stones where they got their shit from. Chuck Berry, that’s where!”

“Well, now,” Stevie said, swinging his head toward the reporter, “that’s not actually … uh …that’s not necessarily…” He fondled the radio on his lap and pulled his upper lip tight against his gum like Humphrey Bogart. “That’s not the best way of putting it,” he said finally.

The reporter looked wounded. “How can you say that?” he asked weakly. “I mean just listen to what’s being put out, man…” He was beside himself with distress. “You should relate to this, man. After all, you’re a black performer.”

“You’ll excuse me,” Stevie said gently, “if I say that is not the case. I don’t consider myself to be a black performer; I consider myself to be a performer who is … uh … black. That’s a different thing.”

“The different between commitment and categorization,” the filmmaker in the green turtleneck offered. “Perhaps.”

“The what?” Stevie said.

“Well, you’re black,” the filmmaker said, edging to the front of his chair, “and you identify with that strongly. It’s a dynamic part of you personality, which in turn,” he flip-flopped his hands as if he were performing a magic trick, “you inject into your music. However, your music is not necessarily limited by or contained within the categorical boundaries of black music.”

The man looked about him earnestly; his words hung in the air like freshly strung Christmas decorations. The room was a study in concentration for several moments.

“Exactly,” Stevie said at length.

“Whatever it is,” Tucker said, standing and stretching his arms, “it’s cool. You got anything to drunk up here, Steve?”

“I don’t know, big brother Tucker,” Stevie told him. “Why don’t you just take yourself into the refrigerator box and see what’s happening?”

Tucker edged his way into the kitchen and looked inside the refrigerator.

“There is, I believe, some apple juice,” Stevie said, “someplace.”

“I hope it’s organic apple juice,” Tucker said, taking a bottle out and holding it under his nose. “I can’t dig it unless it’s mother nature’s own.”

“Man, you gotta be riding,” Stevie said. “I got my own apple-juice-making machine in there. All electric and automatic …uses real apples and everything.”

“I have to tell you, Steve,” Tucker said, returning with a glass in his hand. “I’m impressed. A dude who has his own apple-juice machine is a dude who has arrived.”

“Yeah, well I’m not doing all this shit for nothing, you understand,” Stevie said.

“Right on,” Tucker said agreeably. “You’re reaping the benefits of your station in life. It’s the superstar bit.”

“Superstar!” Stevie cried, clapping the arm of his chair. “You’ve been reading Newsweek, Tucker!”

“Newsweek it out to lunch, man,” Tucker said. “They think they discovered Steve last week or some such shit. Made him what he is today.”

“Jiveass piece,” the reporter said again.

“Well,” Stevie said, “see the thing is … the thing is this.” He settled back in his chair and folded his hands on his lap; he gave every appearance of having nothing further to say.

“What,” Tucker asked after several moments, “is the thing?”

“That they have it all fucked up,” Stevie said simply. “I mean Newsweek comes out with their story and everything and there I am on the cover for America to see … which is cool … but it seems to me, as I understood the piece, that they missed the whole point.”

“In what sense do you mean that?” the filmmaker asked.

“In the sense that they missed the point,” Stevie answered. “They’re going on about me, saying how I’m this and that and now I’m a superstar. Well, I say supershit! It was like … I mean it was as if they decided that black music was the thing that was going on now. It was as if they looked around and said … hey! there’s black music going on! And then … then … in attempting to understand this … uh … new-found thing, they had to go find some black cat who … ah … somebody who by what he does … uh … oh shit, Tucker,” he said, snapping his fingers in midair, “what word am I looking for here?”

“Symbolizes,” Tucker said. “They wanted somebody who symbolizes the phenomenon. Such as it is.”

“Right!” Stevie said. “They’re looking for a symbol of all this that they thing is going on.”

He threw his head back and grinned hugely.

“And that’s me!” he shouted at the ceiling.

“Yes, maybe that’s so,” the filmmaker said evenly. “But on the other hand you must admit that your accomplishments have been impressive. We may be talking about specious labels here…” He looked around the room to see whether or not that was the case and received no response whatsoever. “Still,” he went on, “I imagine that given contemporary standards you are a superstar, realizing of course the context in which that tile is employed by the media and the need for the public to seek out and identify … or even to relate…”

The filmmaker’s conversation slowed down, spluttered out and died, like a car running out of gas 40 miles out of Las Vegas.

“Yeah, well forget that,” Stevie said. “I mean no offense or anything. I’m not putting you down personally, I hope you understand. It’s just that … well, look. People are always labeling … as a performer … rather than listening to whatever it is you’re doing and … uh … accepting you for what you are. I mean they’re always trying to comprehend you, you see, and they think that by saying, hey, I got that cat’s label—you understand?—that they have you all figured out. You can say … uh … well this dude here is obviously a rock singer … or this cat here is a country-western thing … you know? So now that I know what he is, I know all about him! Well, you don’t know shit!

“It gets to be a ridiculous situation when I come out with a record and some people will say … my, my! … that doesn’t sound like Stevie Wonder. Well, shit. How can I not sound like me. That’s not my problem, when that happens. That’s the problem of somebody who has…ah…jumped to conclusions too quickly.”

Stevie stood up and began to move across the room.

“Some folks can’t help but just trying to understand you a little too fucking fast,” he said.

“Perhaps the public,” the filmmaker suggested, “is conditioned to resist change.”

Tucker drained the last of his apple juice and regarded the man good-humoredly.

“You know you are really heavy, man,” he told him. “I say that in all seriousness.”

The filmmaker smiled uncertainly.

“It’s not so much the public,” Stevie said, hunting around in a stack of cassettes. “It’s record companies … who naturally assume that they know everything there is to know … and they’re telling you what you can and cannot do. What the public will accept. But, like, how do they know they won’t accept something if nobody ever does it? Crazy things like that. Also, the people who write about perfumers and artists…”

Stevie turned his head and smiled at the young reporter.

“Don’t take this on a personal level,” he told him.

The reporter hunched forward and rested his elbows on his knees; he looked as if he were carrying a great weight on his shoulders.

“People who write about performers can really get into some weird shit,” Stevie said. “I don’t know if either of you folks are familiar with my show but … uh … on this past tour I decided to do something a little bit … different. I thought instead of just going out and doing all Stevie Wonder’s Greatest Hits and everything. I’d do some songs that I’d encountered along the way and that I admire very much. So I did ‘Earth Angel,’ the Penguin thing, and some Temptations stuff … ‘Ain’t too Proud to be Beg’… and ‘I Heard it through the Grapevine,’ ‘What’d I Say’ and just a lot of tunes that I really liked. You understand all that? Then I finished up with ‘Fingertips,’ Right?”

Stevie began to clap his hands and dance around in the middle of the room.

“Everybody say Yaaayyyyyyy….” he sang.

“Yay,” Tucker said idly.

“And you wouldn’t believe,” Stevie said, still weaving about, “what some folks made out of that. People were saying …oh goodness, that boy’s all washed out. They said I was lowering myself because I was doing all this shit. Now, I was enjoying myself … and the audiences, they were enjoying themselves … and yet people seemed to take this as a sign that I was never going to do anything worthwhile again. Which is stupid, naturally.”

Stevie danced over to the tableful of equipment and fed one of the cassettes into the tape deck.

“Allrigghhht!” he cried, as the music came out of the speakers. “It’s Stevie … aghhhhhh!! … Wonder! Ba ba dee doo doo ba…”

He twirled around drunkenly, like a sailor coming back from shore leave.

“Will you look at this?” Tucker said. “Have you ever seen such grace?”

Stevie slapped his hands together happily and bounced around the room like a pinball. The filmmaker watched his performance with detached curiosity of someone taking a bus through Europe.

“I tell you,” Stevie said breathlessly, coming to a stop. “I love to perform. All this superstar shit can go out the window.”

“But it’s a platform, man,” the reporter protested. “A place to stand … to be heard…”

He drove one fist into the palm of his other hand for emphasis.

“Well obviously you don’t get the opportunity to perform,” Stevie said, “if people don’t know who you are. But when you start to believe the things you read about yourself…like when you begin thinking that you really are number one … that’s when you begin to go nowhere. I mean if there really was such a thing as number one, well then whoever that lucky cat was would have no place left to go. You see? that’s why I don’t go for that whole thing. It’s like … uh…”

“Limiting,” Tucker said.

“Limiting,” Stevie said. “Just like when you say I’m a black musician…you know…’Stevie Wonder does black music,’ all of that. That’s putting me in a particular box and saying … stay … right … where … you … are!”

Stevie whooped merrily and began to shimmy again.

“And you know I just have too much energy for doing that,” he said.

“Don’t you love the guy?” Tucker asked the two men on the couch. “He’s a philosopher, man, in his spare time.”

“I just dig audiences,” Stevie said. “That to me is the most worthwhile thing about this whole business. Just people coming to have a good time and letting me sing for them. Tell the truth, Tucker, didn’t we have a good time on this tour?”

“Pretty much,” Tucker said. “But then again … there awesome weird folks running around out there, Steve.”

“Aw, c’mon,” Stevie said. “They were terrific, every place we played. You know, I feel like those people … I think of them as my best friends in the whole world.”

“Well, of course, your perspective is a little different than mine, Steve,” Tucker told him.

He turned to the filmmaker and the reporter.

“Dig this,” he told them. “We were playing Boston, and Steve here is just about finished with the show, ‘Superstition’ is the last hit and then we split, okay? So I’m standing up there on the side of the stage saying, ‘Lucky us, we made it through Boston without any craziness.’ Then I see some guy, a black dude, way at the back of the platform and he’s standing on the light cables. One of the technicians comes over and says he thinks maybe if that guy stands there like one minute longer, he’s going to go up in flames and take the whole place with him, right? The technician is afraid to tell the guy to move, ’cause he’s black, dig, so he asks me to tell him. So I go on over. Now this cat had to be seen to believed. He’s all dressed up like Chicago in the Thirties; has himself a white silk suit and a black silk shirt and a white tie and he’s wearing this absurd white hat. But it’s cool with me, just as long as he steps off the cable. So I go tell him to move, polite as can be and suddenly … bam! … the guy pulls out a gun. Pulls out a fucking gun! And right then, Steve kicks into ‘Superstition’ and the whole stage is just a deluge of weirdness; lights going, sound effect, all sorts of shit. And this is fucker is waving his piece around, shouting and acting outrageous, unloading a whole truckload of ‘motherfucker’s’ and ‘fuck you’s.’ At this point I am completely paralyzed and my life is flashing in front of my eyes: I just keep staring at this mean little gun that’s aimed right at me.”

“And so what happened?” Stevie said. “He shot you?”

“Yeah, right,” Tucker said. “With you playing as I bled. I mean just imagine this shit taking place.”

Tucker made a toy gun out of his hand and fired into the air.

“Finally,” he said, “some of the security people got hip to what’s going on and they creep up in back of the motherfucker and grab him around the waist and drag him off the stage. All the while the guy is shouting, ‘Stevie Wonder’s a faggot! Stevie Wonder fucks his mother!’ Says he’s going to kill us all if we turn him loose for a half a second. So the bouncers take him into the backstage area and push him into the bathroom. Then they just beat the shit out of him. Left him with his head floating in one of the toilet bowls.”

Tucker leaned back in his chair and swung his leg over one of the arms.

“I should have told him, Steve,” he said, “right before he blew me away, that he hadn’t ought to do that ’cause after all … I’m one of the best friends you have in the world. And it just isn’t polite to spoil a friend’s gig.”

Stevie considered the story for a thoughtful interval. Then a large smile appeared on his face.

“Well, it’s like you said, Tucker,” he told him, “your perspective is different from mine.”

Stevie found Tucker’s shoulder with his hand and gripped it tightly.

“You can’t feel what all those crowds are like unless you’re out in front playing for them. Because, man, when I look out at the audience,” he said, tapping his sunglasses with his fingernail, “all I see are beautiful people.”

The two people from Human Kindness Day sat in a booth in Feathers watching for Stevie to come downstairs.

One was a muscular man with large sorrowful eyes and enormous hands; but his hair was lined with ribbons of gray which ran like small tracks to the back of his head. His partner was a frail, neurotically composed white woman whose eyes blinked constantly from unspoken anxieties. She drew aimless circles on the table with her forefinger and glanced around the restaurant with apprehension.

“He’ll be down any minute,” Ira Tucker said. He sat across the table from the two and watched the woman’s blinking eyes.

“One thing you can depend on with Steve,” he told them, “is that he’ll always be late. That’s his way of doing things. When we were in England last year, it took Steve three days to get on a place and leave London. Each day we were supposed to split and each day Steve just couldn’t get it together enough to pack. But you just have to go with it. I sat in my hotel room the whole time watching one of the mellowest snowfalls I’ve ever seen.”

The black man looked at Tucker with obvious sadness, as if there were far too many things in the world that could not be properly explained.

“At least,” Tucker said, “I think it was snowing.”

The woman with the blinking eyes pulled a Kleenex out of her purse and blew her nose; the story apparently offered her no consolation.

“When we were playing Detroit on this last tour, Tucker said, “Steve was 40 minutes late in going on or something. Everybody’s going crazy, you know, having heart attacks because Steve is just sitting in the dressing room trying to get his hair to look right. But I wasn’t worried. I said listen, folks, there’s no problem here; no reason to panic. After all, Steve was in the place; eventually he’d go on and then everything’s cool. Then a couple weeks later, we’re in Seattle. Rufus is onstage doing the opening act and Steve is due to go on in 30 minutes, the only hangup is nobody’s seen Steve since the day before. Suddenly, dig, as the tension mounts, the phone rings. Guess who? Steve! He was calling fro L.A. to say he missed the plane. Missed the plane. And he’s supposed to be onstage in 30 minutes.”

Tucker took a pretzel from a basket on the table and munched it with satisfaction.

“Man,” he said, “that one just blew a lot of people away. And I said, okay … now we have a problem. Now anybody who wants to panic can go right ahead.”

The woman from Human Kindness Day was visible disturbed. She opened her mouth as if to speak but no words came out.

“That,” Tucker said, “is life with Steve.”

The woman shivered and pulled her arms around herself. She looked away from Tucker in the director of the adjourning booth; it was occupied by a young man with should-length hair and a cowboy har. She was amazed to find him waving at her.

“That man over there,” she said, “…he’s waving at me. I’ve never seen him before.”

Tucker looked at the young man who waved at him also. Tucker saluted him in return.

“That’s Robert Friedman,” he informed the woman. “He digs people.”

“Robert’s a Village item,” Tucker said. “He’s into movies of a weird order; he’s done stuff in Europe with Fellini and people like that … luncheon shit. He want’s to be Steve’s media coordinator.”

Robert Friedman continued to smile benevolently. He had three Brandy Alexanders sitting in front of him which he would study closely from time to time, smiling secretly at himself; then he would look up again and haze out blissfully at the restaurant. When Stevie walked in, Robert called out to him.

“Robert?” Stevie said.

He turned his head slowly, like a radar-tracking device.

“Crazy, Robert,” Stevie said, edging closed to the booth. “What kind of trouble are you getting yourself into down here.”

“Well, I have three drinks here,” Robert observed, “and I cannot decide which glass to drink from. Maybe…”

Robert looked up at Stevie, whose head was nodding with attention like an analyst’s.

“…maybe I should just order a new one and have them take these away,” Robert said.

“Yeah…” Stevie said, after a moment’s thought. “I knew it was you.”

Tucker came over and took Stevie by the arm. He led Stevie over to the table and introduced him to the Human Kindness Day people.

“These folks, Steve, are terrific people. Don and Carol—this is Steve.”

The black man who was Don took Stevie’s outstretched hand and shoot it firmly. Carol looked up and made a twittering sound like a bird coming out of and egg.

“I’ll leave you all to chat,” Tucker said, easing Stevie into a seat. He pointed with his thumb in the direction of Robert Friedman. “I’m going over your yonder to hang out with Buffalo Bob. Call if you need me.”

“Ira,” Robert said, squinting up from under the brim of his hat. “I’m having a terrible difficult time relating, man.”

“I can relate to you, pardner,” tucker said. “You’re the midnight cowboy.”

Robert nodded. “I think that chick at your table is about to flip,” he whispered to Tucker. He stared at Carol and waved again. “She’s got electric eyes, man.”

Carol caught Robert’s wave with the corner of her eye. She fluttered her hand next to her face to shield him from view.

“Well,” she said with a strained voice. “I’m so happy we finally have a chance to talk to you, Steve…”

She paused for a response but Stevie kept silent and pulled at an ornament hanging around his neck.

“I don’t know how much you know about Human Kindness Day,” she said. “We sent some literature—”

Her partner cut her off with a sweep of his hand.

“Let me lay it on what we’re basically about,” he said.

His large eyes strained outward from their sockets like caged birds.

“Human Kindness Day is on the order of a celebration,” he told Stevie. “A total concept thing. We gather as many voices as possible together and concentrate on the dynamic and beautiful power of human warmth—brothers and sisters rapping, tuning in on the goodness that surrounds them, conscious of problems but at the same time optimistic and looking forward, dig—seeking solutions—and we take all these positive things that are a result of people coming together and sharing themselves with other and we reach out and say—Yes!”

The black man closed his fist dramatically in midair, clutching at nothing. Stevie regarded him with the utmost gravity.

“We make one person the focus of the celebration each year,” Carol said. “We dedicate Human Kindness Day to that person.”

“And that person,” Stevie said, “is … uh … me. Right?”

“We would be delighted,” Carols aid, “if this year we could have Human Kindness Day Honoring Stevie Wonder.”

She spoke as if she were reading off a theater marquee.

“The last two years,” Don said, “We’ve had Dick Gregory and Nina Simone—”

“Everybody said Nina Simone wouldn’t do it,” Carol interrupted. “But I believe we toucher her with our enthusiasm…”

Don silenced his partner again by restraining her arm.

“But this year,” he went on, “We’re trying for an even bigger event than we’ve had previously. That’s why we want you to hook up to this, man. You have such a heavy impact factor. It would give us national posture.”

“Yes, well…” Stevie said. “See, that’s the basic problem with what you’re saying.”

A spasm of alarm slithered across Carol’s face.

“Problem?” she asked.

“That’s right,” Stevie said.

He ran his fingertips underneath his glasses and rubbed the corner of one eye.

‘See,” he said to them, “I’ve always tried to avoid doing this sort of thing you’re speaking about … not that I don’t think that what you’re doing is a beautiful thing, you understand.”

Carol nodded unhappily, holding herself in readiness for rejection.

“Oh, Steve,” she said, “it’s a very beautiful thing.”

“I’m sure it is,” Stevie said softly, “I’m sure it is. But … if you’re actually speaking about a day that is … ah … dedicated to brotherhood and love and kindness—which, as I say, is a very important thing … as a matter of fact, this sort of celebration is something of a personal dream for me—”

“I knew you would relate to this solidly,” Don said.

“Well, to the concept, yes,” Stevie said. “I relate to your purpose, you see. But as far as honoring me … uh … as far as making this a Stevie Wonder Day, so to speak … I think that’s a mistake. Because that takes the focus away from the real issue and the real concern—namely human kindness—and puts it onto me … um … where it really oughtn’t to be. Do you see my point here?”

“No, man,” Don said quickly, “that’s not the thing at all. This is a function of community, man. We’ve got school-children in on this and everything. We run art contests, poster contests; kids write poems for this. It’s far-reaching.”

“It belongs to the people,” Carol said.

“Exactly,” Stevie said. “That’s how it should be. However…”

His head rolled suddenly from one side to the other, as if caught by a breeze.

“…it has a way of getting away from the people and concentrating on … uh … individuals. Such as myself.”

“I can assure you—” Carol began.

“Oh, I know you can assure me it’s cool,” Stevie said. “But you have to understand how it is for me … as a performer.”

“We’d respect your inputs, man,” Don said. “It would be your thing, any way you want it to be.”

“Right on,” Stevie said. “that’s exactly what it would be—my thing. What I am attempting to explain is how uncool that is. See, this is what is personally very upsetting about my … uh … position here. Because my inclination s to help people whenever I can. I feel like that’s a responsibility of mine, you know; I feel it necessary to give something back to people in return for all that they’ve given me. This is a compelling thing, you understand.”

Carol’s eyes were blinking spasmodically; her fortitude began to slip away, like water going down the drain.

“We are also compelled,” Stevie. A dreadful smile appeared on her face.

“Uh … yes,” Stevie said. “Naturally you are. But as for myself, I know from experience that when I become involved with something like what you’re proposing to me now … suddenly … it’s no longer a true thing. People forget about the violence going on in cities. People forget about the wars that are being fought. People forget all the problems that they started out to deal with. Instead of the attention being where it should be—where it started out being—now you have Stevie Wonder in Concert. Now nobody wants to hear about what they can be doing to make the world a better place. They just want to hear me sing ‘Superstition.’ Which is not the way it should be.”

“You don’t have to perform,” Don insisted. “That’s not where we’re at…”

“But that’s where I’m at,” Stevie said. “That’s what I do. That’s what people expect me to do. And that’s how I make my contributions, you see? That’s my way of telling people what’s on my mind … that’s my way of telling them what concerns me. I want to make it clear to you that I take what I do very seriously; and since my accident, I suppose I take it even more seriously. Because from that point on I realized that I was just lucky to be alive … you know? … and it became very clear to me that it wasn’t enough just to be a rock ’n’ roll singer or anything of that nature. I had to make use of whatever talent I have. So when I get on a stage and perform. I’m saying something to people; and I’m saying it in the way that’s the most effective for me.”

Stevie paused and stroked the hair that curled under his lower lip with great concentration.

“When an audience comes to hear me perform,” he said, “they know I’m not going to put them to sleep with my moral indignation, dig it? They know I’m going to do a show, which is why they came. So I give them their show; I entertain them—because I am an entertainer, regardless of what a lot of people think; I’m not a politician or a minister—but at the same I can … ah … enlighten them a little.”

Stevie placed his palms flat on the table and beat a light tat-too on its surface.

“I speak though my music,” he said, “because that’s where my credentials are. And people know, when they hear me, that I’m not selling them anyone else’s product. They know I’m speaking for myself.”

Carol produced her Kleenex again and dabbed it under her nose. She allowed the tissue to dangle from her fingers and sniffed heavily.

“I think that chick is about to go bongos at any moment,” Robert Friedman said, peering a her from his seat. “Is she stoned?”

“No, man,” Tucker said to him. “She’s just high-strung, that’s all.”

“I’m stoned,” Robert explained.”But I maintain, Ira. That’s important.”

“Vital,” Tucker said.

“I got stopped by the police driving up here,” Robert went on. “And I was fucked up, as you might guess. But I maintained, man. I kept cool. I demanded to know on what charges they were delaying my journey. You have to keep a strong profile when you deal with the authorities. You have to be forceful but not obnoxiously so.”

“Move like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” Tucker said.

Robert Friedman nodded judiciously.

“But sometimes,” he told Tucker, “you absolutely cannot maintain. Sometimes it’s impossible to relate.”

Robert suddenly left to his feet.

“How can anybody maintain in this hotel,” he demanded. “There’s no way! The dam has broke, Ira. The shit is on the loose.”

Robert Friedman’s cowboy hat fell of his head and crashed onto the table.

“Slow down, hoss,” Tucker said, handing the hat back. “The movie isn’t over yet.”

He felt a tug at his sleeve and looked up to see Stevie standing next to him.

“Robert was about to get on his steed and ride off into the sunset,” Tucker told him.

“Solid,” Stevie said absently. “Listen, Tucker, I have to speak to you. I want to know where you get these people that you keep bringing to me.”

“Those folks over there?” Tucker asked. “Why, they’re from Human Kindness Day, man. Didn’t they tell you what the hit was?”

“Yeah,” Stevie said, “they told me. They want me to perform, Tucker. That’s what they want.”

“They don’t want you do any such shit,” Tucker said.

“They say they don’t,” Stevie said. “They always say they don’t. But then you show up and suddenly there’s a piano and a microphone and how about doing just one small set? I mean that’s how it always goes down, Tucker.”

Stevie bent over and brought his head next to Tucker’s ear; he lowered his voice to a whisper.

“I mean, I tried to deal with the philosophy of the issue,” he said, “but they keep pushing the gig. It’s upsetting me tremendously.”

“Don’t do anything you aren’t getting paid for,” Robert Friedman said. He had slumped back in his seat and had assembled himself into a configuration of severity; his eyes were as flat and glassy as a skating rink.

“Okay,” Tucker told Stevie. “I’ll go back over there and straighten it out. But you know something?”

“Tell me,” Stevie said.

“You’re probably going to end up helping those nice people out. Do you want to know why?”

“Because I’m a good guy,” Stevie said with a smile. “I’m a pussycat.”

“No, man,” Tucker said, standing up. “That’s not it. You’re going to do it because you’re a committed person.”

“Right,” Stevie said. “I figured that was it.”

Tucker put his arm around Stevie’s shoulders and began to walk with him back to his table.

“Face it, man,” Tucker said. “You gotta do what you gotta do. You’re a professional, after all.”

Stevie looked at Tucker and grinned furiously.

“A professional,” he said. He stamped his feet in delight. “Ain’t that just right!”