(as told to W.C. Heinz)

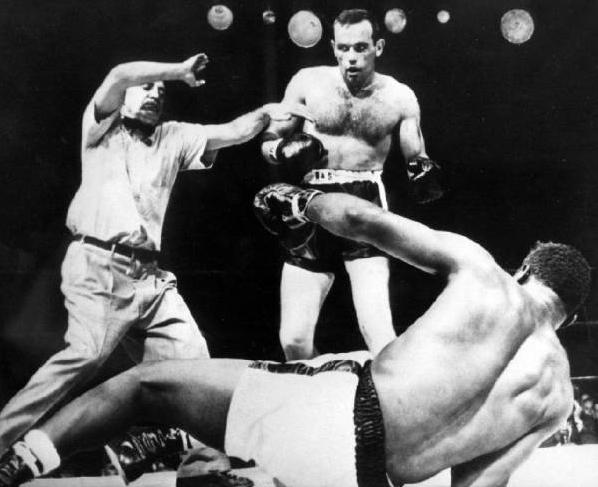

For almost a whole year I’ve seen it day and night, maybe a thousand times. Me and Ingemar Johansson boxing and Johansson sticking out that left jab and me ducking under it, and then I’m down and I’m looking right in the face of John Wayne.

John Wayne is my favorite movie actor. Every picture I’ve ever seen him in I’ve liked him, because he’s always the good guy, cleaning up the town or something. I’ve never met John Wayne personally, but here I am defending my heavyweight championship of the world, and what is John Wayne doing here in the first row of the ringside, and what am I doing on the floor looking right at him? (There’s a lot I don’t learn till later).

Third round. I see Johansson sticking out that left jab and then I weave to the right and I make him miss. Johansson’s jab, it doesn’t hurt you, it’s just in the way. I’m throwing hooks, trying to lure him into a position where we can swap punches. I figure I’ve got more speed in my hands than Johansson has, so I want to use speed, and then he jabs again and I duck under and then I come up—into a black spot.

I hear the referee say something about “neutral corner.” I’ve knocked out 26 men in my professional fights, so I figure I must have knocked Johansson down. I don’t know that he’s knocked me down, but now I’m standing by the ropes and I start to walk to a neutral corner and then I feel a tremendous shock at the back of my neck and it’s like I was run over by a truck.

They tell me that’s when he hit me on the back of the neck. I don’t remember getting up, but I remember Johansson coming to me and I can hear the noise of the crowd. I throw a couple of punches and then it’s like the black spot comes again. Then I see myself getting up and throwing punches and then comes the spot once more.

In the dressing room I don’t remember what the reporters asked me or what I told them.

The next time there’s no black spot, but I’m groggy and there I am looking into John Wayne’s face. We look right at each other and he’s just a few feet from me and then I get up.

All I can figure out is that John Wayne has seen me down. The last time there doesn’t seem to be anything wrong with me, but I hear the referee say: “That’s all.” Then I realize that I have lost the heavyweight championship of the world.

In the dressing room I don’t remember what the reporters asked me or what I told them. I just remember that when they went away and I got dressed and went out to my car there were a lot of colored people there, patting me on the back and telling me they were still with me.

When I got in the car my wife was waiting for me and I put my head on her shoulder and she put her arm around me, and my brother drove us home. All the way home to Rockville Center, Long Island, we didn’t say anything, because my wife understands that I don’t want pity, ever.

For some reason I never could stand people feeling sorry for me. That’s why I don’t like it now when people say: “That was a lucky punch Johansson hit you with” or “You’ll get him the next time.”

The way I think, there’s no such thing as a lucky punch. Any man can knock another man out if he hits him just right, and I’m the only one who knows what I’ll do the next time, because for three and a half weeks I didn’t leave my house, thinking about it, except to go to the doctor twice. And I’ve thought about it ever since.

I didn’t sleep good one night in all those weeks and I’m a good sleeper. People are surprised that I can even sleep in the dressing room before a fight, but now I kept waking up in the dark and seeing Johansson knocking me down, and me seeing John Wayne, and then Johansson knocking me out.

For a while I resented Johansson. But that’s wrong, I told myself; all he did to me was what I was trying to do to him. All the same, I couldn’t—still can’t—wait to fight him again.

After three and a half weeks my wife said that she would like to go out to the movies. There’s a theater just about a mile and a half from us, but I still didn’t want anybody to see me, so we went to a drive-in instead.

That was pretty good, because the ticket man didn’t recognize me and I could stay right in the car. When we wanted some popcorn my wife had to go and get it herself, though, and then, a week later, my wife wanted to go to a movie again, so this time we drove to the other theater. We didn’t know what movie was playing, but when we got there, it was right up in lights: “Johansson-Patterson Fight Pictures.”

So we came home and watched television. After my wife went to bed I stayed down in the recreation room alone, seeing that fight again, seeing that picture of Johansson standing over me, and feeling sorry for myself until, all of a sudden, I remembered something.

I remembered that in 1957, when I was champion of the world, I was in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to make an appearance at a charity boxing show. The afternoon before the show a man came to me and asked me would I go to a hospital where there were a lot of people that had cancer.

We went to that hospital and I went through the wards of the grownups and the little children. I stopped and shook hands with them and answered questions and signed autographs, and I remember mostly one little girl. She was as thin as anybody you ever saw and was crying. “That poor child,” the doctor told me later, “she’s only got a day or two to live.”

Sitting in my house late that night I thought about those children, and then I remembered a saying: “I wept because I had no shoes until I saw a man who had no feet.”

That was what got me out of it. I realized that all that happened to me was that I got knocked out, and I would have a chance to fight that man again. I was getting well paid, and I looked around at all the luxuries being a fighter brought me.

The truth is, I never had a whole suit of clothes until I was 15. When I became a fighter and had about 10 fights, I had bought 35 suits.

My mother had 11 children and she worked in a bottling factory and she never went out for a good time. After I had made more money I bought her a 10-room house in Mount Vernon, New York, where she could raise my eight younger sisters and brothers. I bought her a mink scarf even, and now she belongs to a church and goes out and she actually looks younger now than she did before.

I was able to set my brother, Frank, up in a floor-polishing business. I bought my brother, Billy, a restaurant. I realized now that I had all these things and that I should get down on my knees and thank God. I did, and then I went upstairs and I slept the whole night through for the first time in four and a half weeks.

When I got up in the morning I said to my wife that I guessed I would go out. I said I would take our daughter Seneca to play in the park, and when I came back I had thought of a kind of a joke.

I think Johansson is carrying the title so much better than I ever did. He is displaying the poise and showmanship of a champion better than I did.

“You know.” I said to my wife, “I’ve knocked so many men down and stood over them. but all the time I was walking through the park just now nobody recognized me. Then I sat down, and as soon as they saw me sit down the other people said: ‘Oh, now we recognize you. You’re Floyd Patterson.’ ”

My wife laughed and I laughed. It was the first time we’d laughed in all those weeks.

After that night. I could figure out exactly what I did wrong. You have to be respectful of the man you fight, and you have to be a little nervous and then you get away from punches and you take advantage of everything that happens. When I fought Johansson I didn’t feel like that.

Seven weeks before I fought Johansson I fought Brian London from England. I boxed 500 rounds in camp for London. and after I stopped him in the eleventh round I went back to camp and I boxed 80 rounds more for Johansson.

Even when I was in camp I should have known something was wrong. Usually, when I’m going to fight somebody, I can see him when I run on the road or when I punch the bag or when I’m in bed at night. Before I knocked out Archie Moore to win the heavyweight championship of the world I saw that fight over and over.

I’d see Archie make a move and then I’d make a move and once I even dreamed that I’d knocked him out. It woke me up, and for a minute I even had the good feeling that I was already the heavyweight champion of the world. Everybody says now that that was my best tight.

But in my mind I never could see Johansson and me boxing. I tried, but I never could get the vision of it because I must have had it in my head that the only good tighter he ever beat was Eddie Machen and I was just too confident.

On the night of the fight we went to the Yankee Stadium about 7:30 and I just took my coat off and lay down on the rubbing table and took a nap. Then I got up and put my boxing things on and got taped and took another nap. Finally the man from the boxing commission came in and he said: “All right. champ, you’re on.”

Always I take a look to see how big the crowd is, but this night I didn’t look. Always it’s a long wait in the ring, while they introduce other fighters and put on the gloves and play “The Star Spangled Banner.” This time I don’t even remember them playing “The Star Spangled Banner” or the Swedish National Anthem.

Always I measure the applause with my ear, to see how much the other man gets and how much I get, but this time I didn’t even hear the applause. I just remember my corner saying, look out for his right hand, and then the fight started. After that it was like I was just boxing some more rounds in the gym.

That’s what I did wrong, underrating Johansson like that. I know it can’t happen again, because for months now, training up here in Connecticut since the first of September, I can see Johansson. I mean I can see Johansson and me boxing, the way he moves on a line and sticks out that left jab and the way I move off it the next time we fight.

For a while, in that first fight, I was beginning to figure he didn’t have that great right-hand punch—then he threw it. Next time I’ll know better, but what I’m going to do about it you’ll have to wait another month to see.

I’ve got a real good picture of Johansson now. When I met him before the last fight, he just seemed to me to be kind of nice looking and kind of nice spoken. Now I can see him as a fighter.

I think Johansson is carrying the title so much better than I ever did. He is displaying the poise and showmanship of a champion better than I did.

My friends say to me that’s not my fault, that it’s harder for a Negro to perform on TV than for a white man. I know all this, but that’s not the reason. The reason is that when I had the title it was almost like there was no champion. Even in my own mind it didn’t seem to me that I was like Joe Louis or Rocky Marciano, and that’s the way a champion should be.

When I was growing up, like from about 11 years old until I was 18, Joe Louis was my hero. Then l became champion, and it didn’t seem right. Actually, when I finally did meet Joe Louis the first time I looked at him like he was still the champion and I wasn’t.

Right after I won the title they had a torchlight parade for me one night in Mount Vernon. There I was, riding in an open car, and all I could think was that this is what presidents and kings should do, and not me.

I used to think if I ever won the title the hardest part would be over. When you’re just one of the pack you want what somebody else has, but when you win the title everybody wants what you have.

Within a couple of hours after I knocked out Archie Moore and won my title. I couldn’t eat in a restaurant—it made me nervous, everybody staring at me. And I couldn’t go to Coney Island and ride the parachute jump and the horses and the cyclone and stand around and eat popcorn. Being pointed out made me uncomfortable.

But that’s what Johansson has taught me. I have to learn to wear the title the way he does. When you are the heavyweight champion of the world you owe it to the people to be seen and to be like a champion, and if God is willing and I win the title back, like I believe I will, I’ll try to be like that.

[Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons]