You probably don’t know Arnold Hano. How could you? You live in a world of bullet points and exclamation points, a place where sportswriters aspire either to the pomposity of ESPN’s “Sports Reporters” or to the cacophony of “Around the Horn.” Where once a journalist would worry about supporting an argument with keen observations or weighty statistics, all that seems necessary now is a good set of lungs to shout down dissenting opinions.

Arnold Hano is more than this. If you do know him, you’ve probably read A Day In The Bleachers, Hano’s account of the first game of the 1954 World Series. Or you might’ve read some of the pieces he wrote for Sport magazine or Sports Illustrated over the ensuing thirty years. If you’re a television watcher, you might have come across some of his profiles in TV Guide, and if you’re a fan of pulp fiction, you’ve undoubtedly read one of his dime-store novels.

I knew all this about Mr. Hano before I met him this past February. In some ways, he was exactly what you would expect from an eighty-six year-old man. He was direct and to the point and didn’t bother with unnecessary chitchat. We spoke on the phone twice, and when I asked if he’d consent to an interview, he started out by interviewing me. He asked about my interests and questioned my intentions. He wasn’t suspicious, he was just wondering why I wanted to talk to him and if I would be worth his time. Even when we finally agreed on a date, he offered to give me thirty minutes or so, with an option for more “depending upon my ability.” We ended up talking for close to two hours, the greatest compliment he could’ve given me.

Mr. Hano and his wife live in the tiny town of Laguna Beach, a city best known for its art scene and a television series on MTV. I walked up the steps to the house on a crisp Sunday morning and was greeted by Mrs. Hano, who led me into a small study, one wall of which was packed with books from floor to ceiling. In the corner sat a small, thirteen-inch television set. Mr. Hano pointed toward it, saying, “You can see that we read a lot more than we watch television.” And with that, we were off.

Hank Waddles: I want to start at the beginning. Tell me about where you grew up. New York City, right?

Arnold Hano: New York City. Mainly I tell people I grew up in the Bronx, and sometimes I tell people I grew up in the Polo Grounds, which is across the river in Manhattan, but I was born in Washington Heights, which is at the top of Manhattan. And then when I was about four years old we moved across the Harlem River and into the Bronx. I grew up in the Bronx and went to DeWitt Clinton High School, which is the high school at the north end of the Bronx, and we were there until I was maybe fourteen or fifteen, when we moved into Manhattan. The formative years were those years between maybe four and fifteen.

Hank: You talk about those formative years. How important were sports, either playing sports or following sports, in your daily life?

Arnold: Both, both, both, both. I played everything, and I read everything, and I followed everything. My father brought home two newspapers every day. He brought home the Herald Tribune and the New York Sun. I said, “How come you read the Tribune and not the Times?” And he said the Tribune was better written. So I was reading sports pages in the Tribune and I started reading Bill Heinz in the Sun when Heinz was just breaking in. Do you know Heinz at all? Great writer.

I played all the ancillary games. I played punch ball, I played stickball, I played stoop ball… There was a game in the playground called box ball, that was a very good game that we played. And then I started playing baseball in sandlot games and Police Athletic League teams and stuff like that. I was a walk-on in my senior year of college as a pitcher. I know looking at me you don’t believe all this, but I was once actually tall. I’ve lost five inches of height to issues with my spine.

Hank: And what school was that?

Arnold: That was Long Island University out in Brooklyn. I’ll tell you about the walk-on later. But I played basketball, I played football, all the sports. I ran, I did everything. I was very involved in sports. I remember when I was a kid we had a stickball league behind our house. There was a length of houses, lots of room. I hit fifty-three home runs in one season, I remember that! [Laughing.]

Hank: That’s so funny, because I remember when I was a kid we had a field, a grass field—it wasn’t stickball in the alley—but I remember keeping track of things like that, how many home runs we had hit in this make-believe season that we played whenever we wanted.

Arnold: That’s right… So I was very involved.

Hank: So did young boys in the ’20s and ’30s, did they dream of growing up to be sports heroes as much as they do today?

Arnold: I did. I can’t tell you their dreams, but I dreamed of standing on the mound at Yankee Stadium and striking out Lou Gehrig. That was a dream of mine, to throw my screwball past Lou Gehrig. Carl Hubbell had been one of my heroes, so I learned how to throw a screwball. I could control a screwball better than I could control a fastball. When my brother and I—my brother was three and a half years older, he was my mentor, he was the greatest big brother anybody ever had. He and I would go to ballgames, and in those days at the end of the ballgame you could run out on the field. We would slide into the bases before the bases were uprooted, and we would stand in centerfield and see whether we could see home plate, because of the mound, and we were little kids. He could and I couldn’t, and that sort of stuff.

It was just a wonderful growing-up experience to have, especially to have the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium across the river from each other within spitting distance. My grandfather was a cop in the New York City Police Department, and he had year passes to the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium, and he left them to me, so I got in to see as many games as I could see every summer. I was a Giants fan more than a Yankees fan, but I was a Babe Ruth fan, so I would do both.

Hank: What was that like, growing up like that? You can’t really relate to that now. Even the Mets and Yankees are far apart, and the Dodgers and Angels here aren’t even in the same city. What was it like with those teams so close together?

Arnold: I’ll tell you even how close it was. We lived in an apartment building in Washington Heights—this was from the time I was born until I was four—where Bob Meusel and Irish Meusel lived. Bob Meusel played left field for the Yankees, Irish Meusel played left field for the Giants. One would be using the apartment while the other was on the road, so they shared that apartment. They lived one story above us. You can’t get any closer to baseball than to have as your neighbor Bob Meusel and Irish Meusel.

I used to ask my father, “Who’s better, Bob Meusel or Irish Meusel?” And my father was very, very diligent about questions like that. He’d say, “Bob Meusel has a better arm, he’s a better fielding left fielder. Emil”—he never called him Irish—“Emil Meusel has more power.” I’d say, “Well, who’s better?” And he’d say, “You have to decide that.”

So having the two teams there, my brother was a Giants fan and I was a Yankees fan up to 1926 when Tony Lazzeri struck out against Glover Cleveland Alexander and the Yankees lost that ballgame by one run and the Series. My brother said, “See, I told you how lousy they were.” So I shifted in 1926 to the Giants, and 1927 began the Yankee dynasty that may have been one of the greatest teams ever. But I didn’t really care because I still remained a Babe Ruth fan. I loved watching him hit home runs.

Hank: Now tell me about Babe Ruth, please. I know…

Arnold: You know the fat guy.

Hank: I know the facts, I know the numbers. But tell me about your memories of Babe Ruth.

Arnold: Babe Ruth was a great all-around ballplayer. People don’t know this, but he stole seventeen bases on two occasions. People think of him as a fat truck, but he could run. He ran gracefully with short steps, funny for a guy who was 6’3” and 210 before he starting getting fat. He took quick steps and he would play right field and catch balls before they went into the bleachers. Very graceful. He didn’t have a strong arm. Odd thing is, he didn’t have a powerful arm, he had a very accurate arm.

Hank: Especially for a pitcher.

Arnold: Yes, for a pitcher. He wasn’t a strikeout pitcher—I’ll tell you about that later, too. He would always throw to the right base. We say that about most outfielders. Ruth always threw to the right base. DiMaggio always threw to the right base. The others maybe did, maybe didn’t. Mays most of the time threw to the right base, but Ruth always threw to the right base.

One day in 1933, the day before the season ended, my father said to my brother and me as we were in the kitchen doing the dishes, “Boys, let’s go to the Stadium tomorrow. The Babe is gonna pitch.” I had forgotten that Ruth did pitch on occasion for the Yankees. Nobody knows this, but Ruth was 4–0 for the Yankees all those years. So we went to see Babe Ruth pitch the last game of the 1933 season. The Senators had already clinched the pennant, the Giants had clinched in the other league, so this was just a nothing game. I thought maybe he’d make an appearance, pitch an inning or two or three—he pitched a complete game. He hadn’t pitched a complete game since 1930, and then he pitched a complete game. And before that he had pitched two four-inning stints for the Yankees, so he pitched four times. So he pitched a complete game, he gave up twelve hits, it was not a great pitching performance, but the Yankees won, 7–5. He didn’t strike out a soul.

Years later I saw him on Broadway. I went up to him and said, “Hi, Babe.” He said, “Hi, kid.” That’s the way he treated everybody. I said, “You know, I saw you pitch your last game at the Stadium.” This was maybe eight years later or so. I said, “How come you didn’t strike out anybody?” And he said, “I wanted those other eight guys to earn their money!” And that was Ruth.

Sometimes in his last years they’d take him out after maybe seven innings and put in Sammy Byrd or some other right fielder for defensive purposes because he was getting pretty out of shape. And we kids, we knew better, we knew the rule, but we’d yell “We want the Babe! We want the Babe!” from the seventh inning until the ninth inning. Once in a while he’d come out of the dugout and he’d lift up his cap or do something like that. We knew he couldn’t come back into the lineup, but that didn’t stop us. That’s the way we were. We loved him, and he loved us, which was very nice. A great combination.

I’d see him in his great polo coat on Broadway sometimes, with his jaunty cap, and his wife and daughter walking along. He was just wonderful.

Hank: Just last night I was reading a piece you did on Babe Ruth for Sport magazine, and you talked about him as being interesting to people because he was a character. He was a great player, but he was a character and so that’s what kind of drew people to him.

Arnold: Yeah.

Hank: It was interesting, it kind of struck me and I was trying to think of that in today’s terms, in today’s landscape, and it made me think of Alex Rodríguez, who is not a character, and I don’t know that anybody really loves Alex Rodríguez, and then you have Manny Ramírez who…

Arnold: Who is a character!

Hank: Who is a character. They’re both great players, both great hitters, but it’s funny how the fans…

Arnold: Love Ramírez…

Hank: Love Manny Ramírez…

Arnold: …and A-Rod…

Hank: …not so much.

Arnold: And sometimes they don’t like him at all.

Hank: Right. Do you see some of that? I’m not saying that Manny Ramírez is Babe Ruth, but do you see some of that?

Arnold: I see that, you’re right. There aren’t many of them. But then there even weren’t that many in those days.

Ruth changed the game. Even though we were there when it happened, usually, historically, you don’t notice when history occurs. We knew history was occurring when he started hitting those home runs, and the game just changed from what it had been. The 2–1 ballgames, the John McGraw games of before—scratch out a run, hit and run, steal a base, sacrifice, all this sort of stuff. And then Ruth comes along and with one swing he changes the game. They changed the stadiums, they changed the size of the fields, everything changed.

And then he was bigger than life. He drank too much, and he caroused too much, but we all knew it. Everybody knew it, but it didn’t seem to matter. You know, he broke the law every day from 1919 to 1934 by having a drink because that was Prohibition. We talk about what Barry Bonds did was against the law—well, it was, but what Ruth did was against the law. But it was different with him. This is a guy who was probably out of shape for half his career, and he played for twenty-one years, something like that!

Hank: I was struck by that. In that article you mentioned something like that. Yes, he lived fast and hard, but he played for twenty-two seasons. I know he hit 714 home runs, but, wow, twenty-two years, that’s a long time for anybody to play. Even in this era.

Arnold: And they don’t have to today. The money made a big difference. Although when Ruth was making his $80,000, that was also an out-of-shape salary. The two most influential ballplayers that I’ve ever been involved with, that I’ve ever seen, are Ruth and Jackie Robinson. They both changed the game dramatically. Okay, what else?

Hank: You talked about how you wanted to grow up to strike out Lou Gehrig, but at some point you must have realized that that wasn’t in the cards for you and that if you were following baseball it would be with a typewriter and a notebook instead of a bat and a glove.

Arnold: My brother taught me to read when I was three years old, so I was reading before the average kid was reading. My folks would bring home books from the library. They would go out on a Friday or Saturday night, and there was a lending library, a private lending library nearby, and they would put a book at my bedside and a book at my brother’s bedside. We shared a bedroom. And I’d get up around four in the morning, take it to the window, and I’d read the book. Anyway, I was involved in reading early on.

And then when my brother put out a mimeographed newspaper in the Bronx when he was maybe eleven and I was maybe eight, I was his reporter. He and a guy named Lester Bernstein—Lester had the mimeograph machine, I guess.

I would run down to the news stands, and I’d copy stuff off and then rewrite it for our Montgomery Avenue News that we put out once a week. I did that for a while, and then I got bored because all I was doing was copying other people’s stories. I decided I wanted to write a story of my own, so my brother, who was a great guy, said, “Write one.” So I invented a cop who would always fall to his knees when he shot the bad guy, and I called it “Sitting Bull.” It was my first pun. Every episode he would be tied to the trolley tracks and the trolley would be coming down, or the bad guys would have him hanging by his fingernails to the edge of the roof and stuff like that. Either I pooped out or the paper pooped out. I did about six or seven of these episodic things. I was eight years old writing the equivalent of a novel for a street newspaper that we sold for a nickel a copy door-to-door.

Hank: Do you still have any of those?

Arnold: [Shakes head wistfully.]

Hank: Really? How much would you pay to have a copy of that?

Arnold: Life. Anything, anything, anything. I suppose if I put something like that on the Internet, somehow, somebody, someplace might know of a copy. That would be great. I’ve thought about it in the past, but I don’t.

So I was writing at that age, and when I went to college—I started college when I was fifteen—I was going to be a doctor. I was taking chemistry and biology and it was taking me for a loop. One day I wandered into the newspaper office and they were laughing. I didn’t know you were allowed to have fun. They were enjoying themselves, so I changed from a science major to an English journalism major in my sophomore year. I became the sports editor of the college weekly in my junior year, and senior year I was editor-in-chief with another guy.

Now that was a good period for Long Island University, because two of those years we won the NIT. The best basketball team in the country at a college that had 700 students. That was rather remarkable, and I covered all those games. So I was writing sports back then. And then when I got out of college I became a copyboy at the New York Daily News and they found out that I knew sports so they’d send me to the games with the photographer. I’d run the pictures back and I could write the captions and stuff like that. So I was always involved. I knew at someplace along the line in my sophomore year of college that this was what I was gonna do for a living. I didn’t know how or what—would it be a newspaper or freelance or a novelist?—but I knew I’d write.

Hank: Here’s one thing that I found out recently. A Day in the Bleachers, which I want to talk about in a little bit, you wrote in 1954, but before that you were already an established writer and you were doing some editing work?

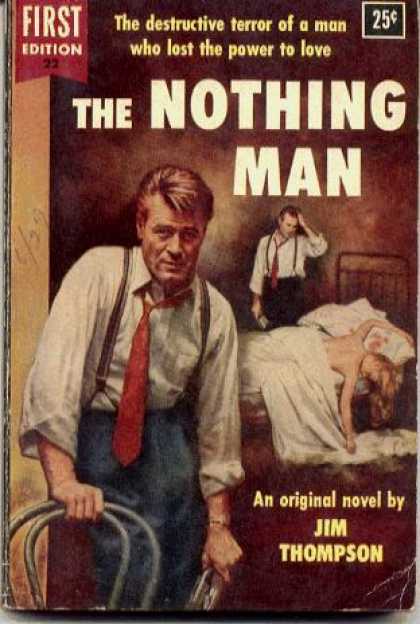

Arnold: I was an editor. I was the managing editor of Bantam Books from 1947 to ’49, so that would’ve been 25 to 27 years old. The woman who was my boss at that time, her husband got called into this odd organization that nobody ever heard of and had to go to Washington, so she went with him while he joined the CIA. And so I filled that spot and became the top editor there. I was the top editor there until I tried to unionize the shop and they fired me in 1949. I answered an ad to start a paperback line and I started Lion Books. These here are about half of the books I put out.

Hank: And these were pulp fiction?

Arnold: Pulp fiction. Well, not so pulpy. Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho, we have an original novel of his called The Kidnapper. Very good. People liked me. As an editor I was never the publisher’s editor, I was always the writer’s editor, and writers liked that.

I drew a lot of good writers. Jim Thompson. You know who Jim Thompson was, right? Well, Jim came in and did maybe ten novels for us in a relatively short period of time. Anthony Boucher was the New York Times reviewer of mysteries, and he started to review our mystery line because of Jim Thompson, and paperback mysteries were never being reviewed. It was the first time, I think, they had ever been reviewed. We did a lot of firsts.

When I was with Bantam I said to Ted Pitkin, who was one of my bosses there, “Why don’t we do All Quiet on the Western Front?” The Erich Maria Remarque novel, it’s the best war novel ever. He said we couldn’t because it was a pacifist novel, and pacifism equals communism. So they wouldn’t do it. So when I went to Lion Books that was one of the first books I did. I did a whole line of anti-war books. Make me a pacifist. Big deal.

We published the only piece of fiction that Leonardo Da Vinci ever wrote. It’s a novel. It’s novel-ish. Robert Payne, who’s a Da Vinci aficionado, he brought it in and said, “Can you use this?” I said, sure, we’ll do it. It’s not good, but it’s Leonardo Da Vinci! I mean, gee whiz! I was the hot editor there, and that was until 1954. There was an Eisenhower recession then, and Martin Goodman, the boss there, cut everybody’s salary ten percent. Well, I had an ex-wife and two kids and Bonnie and the kid, and that was my margin. He was removing my margin. So I figured since I had been writing already, I’d just support myself or not. But I’d rather starve on my own terms, so I quit.

Hank: And that was what year?

Arnold: Fifty-four, and then we came out to Laguna a year later. I freelanced. I was writing stuff, I was writing short stories, I wrote a novella for Argosy and an editor said it was the best thing they’d ever published, and they’d published Hemingway and people like that. So I was a pretty good writer.

I’ve always been a pretty good writer. I don’t consider myself a sportswriter, I considerable myself a writer. I’ve had twenty-six books published; nine of ’em were sports books, seventeen weren’t. I did a novel on Gauguin that I think is a pretty good novel. I did a novel on Sam Houston that’s in the Alamo library, things like that. I did articles for the New York Times on environmental issues. Lyndon Johnson wanted to build a couple of hydroelectric dams in the Grand Canyon and force you all to go long with it. I did a piece for the New York Times about it and what it was going to do the canyon and to the Colorado River, and it killed the project. You’d all thank me personally.

So I’ve done a lot of other writing other than sportswriting. I even wrote the libretto notes for two seasons of opera. I have written everything. From short stories to play reviews to book reviews, everything.

Hank: One thing I wanted to ask that was interesting is I’m wondering how your experience as an editor affected you as a writer, not just as a sportswriter, but just as a writer. Did it affect you, or are those just two separate things?

Arnold: Did it affect me? Being an editor, how did it affect me as a writer? It made me more sympathetic to writers, that much I know.

Hank: Did it make you more sympathetic to editors?

Arnold: No. No. I don’t much like editors. I don’t much like editors, publishers, or agents. And today kids still come up to me and say, “Gee, I’ve written something, who’s a good agent?” And I say, “All the agents I knew are either dead or demented.” Same thing with editors and publishers. I don’t know anybody anymore in that field.

Pretty soon it got to be a cocktail-party feel. You took John Grisham out and gave him five hundred thousand dollars for his next novel, which nobody had even discussed, over a martini or two. I was a better editor than that, and I’m a better writer than a lot of the writing that goes on today where people do that. So writing was not something that I had to do in sports alone, I could do it in other things, and have done it in other things.

Part Two

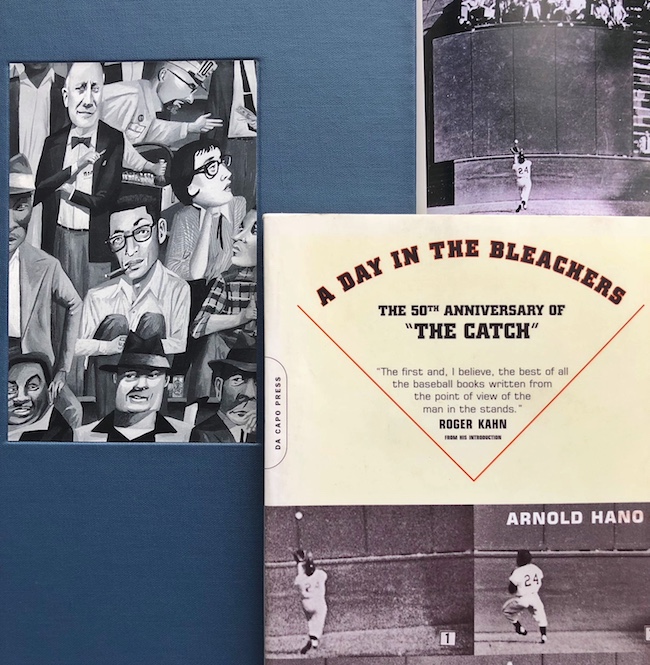

Hank Waddles: A Day in the Bleachers: I just read this book for the first time, I want to say about six months ago. I think one of my favorite things about it—obviously I knew about the game, and I knew about The Catch and the other things that come to mind—but I think one of my favorite things was your description of the atmosphere of the game. Looking back fifty years ago, what was it like seeing a game in the Polo Grounds in the ’40s or ’50s?

Arnold Hano: Well, what it was like seeing a game in the bleachers was the camaraderie. [Shows the covers of three different editions of the book.] When the book first came out, it was a book for fans, about fans. And then the next edition, it’s Willie Mays and fans. And then the next edition it’s just The Catch. But the cover of the first one is truer. This is truly what the book is about.

Hank: Right, right, definitely. It almost seemed like the book was about the fans and, by the way, Willie Mays made a nice catch.

Arnold: That catch, which I spent a lot of time on, took up nine pages in a hundred-and-sixty-page book. And I don’t know if you know about the $700 edition of the book…

Hank: Yes, I read something about that. There was a limited print, and you had signed them all.

Arnold: Four hundred copies.

Hank: The other thing, too, about this book is that now, that device that you used, using the game kind of as a prism through which to illuminate either a season or an era or a career, that’s a fairly common device now. But then, I don’t think so, is that right?

Arnold: You’re telling me about devices. I wrote a book. I wrote a book about a day, and this is the day.

Hank: What I love about this book is that you’re writing the book and you’re telling what’s happening on the field, and Vic Wertz comes up to bat, and then suddenly you have a two-page segue on Vic Wertz.

Arnold: Or on home runs hit by other people for long distances.

Hank: Exactly, exactly.

Arnold: Well, I had to fill some space!

Hank: I think that now that’s pretty common. A lot of people use that.

Arnold: Part of what E.L. Doctorow said yesterday on television is that writers don’t really realize what it is they’ve written. Critics tell them what they’ve written, but he said, “The result is I never read critics. They tell me things about the book….”

Hank: That perhaps aren’t there or aren’t intended to be there.

Arnold: So when you ask me about a device, I don’t know from the device in this case. I wrote a book about a day, and I filled it in with background stuff. I had to establish myself as writing a book with some reason, so I established myself as somebody who’d seen all these other things. And to that degree, I was an historian of this … thing.

But that’s getting beyond where I wanted to go with it. I think of this as a nice little book. Other people think it was something else, but I think it was a nice little book.

Hank: Well, like I said, I don’t know if this was your intention as you wrote it—and it doesn’t sound like you had big intentions—but what I got from it is, I know about that catch, and I knew about that before I picked up the book. But your description of the fans in the bleachers, of what it was like on the field, in the stadium, that’s what I got out of it.

Arnold: When I used to go to ballgames—of course, you don’t do this anymore—I used to go very early so I could watch fielding practice. And until a few years ago, I did not know they had suspended fielding practice. I bet the players union has done that because they don’t want somebody to break a finger.

Hank: Sometimes you hear people complain about that. You’ll be watching a game and someone will throw to the wrong base and someone will say, “Oh well, they don’t have fielding practice anymore, and the only time they do that is in spring training….”

Arnold: Although when you see a guy like Omar Vizquel pull a backdoor double play. Do you know about that at all? Kenny Lofton was at bat when he was with the Dodgers. Men on first and second and I think there was nobody out. They sent the runners and Lofton hit a one-bouncer to second base. Well, Lofton is about as fast going from the plate to first base as almost anybody. So when Ray Durham fed Vizquel for the force play, Vizquel had Lofton in his sights, and he knew that he was not gonna throw out Lofton. So he whirled and he threw to third. The guy who had been on second base was playing his first game in the major leagues. He rounded third and goes two or three steps, and there’s Pedro Felíz with the ball. The most embarrassed baserunner in the history of baseball—who was sent back to the minors that night! A backdoor double play! It was a 4-6-5 double play. I had never seen it before, and apparently he’s done it more than once. And apparently before that play, a few days before, he had reminded Felíz that this was something he might do. Television followed Vizquel off the field at the end of the half inning, and as he reached the first baseline he broke into laughter. He was so pleased and charmed with what he had just done. It was just a great moment. Now there’s somebody who didn’t need fielding practice.

Hank: You know what? I remember when I was a kid I would always make my dad take me to the game when they opened the gates because I wanted to watch batting practice.

Arnold: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Hank: But I do remember watching a version of fielding practice with Ozzie Smith. It was toward the end of his career, and I don’t think he even ended up playing in the game that night. But I’ll never forget this: He was taking balls at short and throwing to second base, never once looking at second base.

Arnold: He knows where it is!

Hank: It’s like Casey Stengel said about Joe DiMaggio, I think maybe you quoted this in your book: “Mr. DiMaggio does not look down at second base as he rounds the bag because Mr. DiMaggio knows that second base has not moved in forty years.”

Arnold: I didn’t write that, I wish I had. Yeah, yeah, but there are only a handful of Vizquels and Ozzie Smiths. In fact, Vizquel and Ozzie Smith are together as the greatest shortstops I have ever seen play that game. And to do it for all those years and all those plays and to always know where second base was without even looking… They used to say that Vizquel didn’t have much of an arm. Well, he never needed much of an arm because he had hands like Bill Mazeroski….

Hank: In and out.

Arnold: The ball was in and out and gone. But when he turned and whirled he threw a bullet. He could throw the ball, he just didn’t have to throw the ball. It’s a lovely sport. It’s still the greatest game.

Hank: Why do you think that?

Arnold: Well, because it has an elegance that football doesn’t have. My wife Bonnie describes football. She says one man bends down and passes the ball between his legs to another man, and twenty-two men fall down. That’s her description of what a football play looks like. And other people have pointed out that after every football play, they have a conference.

Baseball proceeds the way soccer proceeds, with a flow about it. Of course, it breaks up every half inning, which soccer doesn’t do. Soccer is much underrated because of that ongoing flow that it has. Baseball has that flow, but it also has great individual moments. It’s a game where pitcher-batter still is the game, so there is that. I don’t know. Ninety feet was such a glorious invention. Ninety feet. They didn’t miss by an inch one way or the other. It was exactly right. Today, still, a ball hit to shortstop, the throw to first base will get the guy by only this much every time. It’s a wonderfully measured and calculated game. It’s timeless; it can last four hours.

One of the greatest days in baseball history was in 1933 when Carl Hubbell went eighteen innings and shut out the Cardinals 1–0, six hits. Like having two three-hit shutouts, one on top of the other, and it was the first game of a doubleheader, and during daytime. And then Roy Parmelee goes against Dizzy Dean in the second game, and it’s starting to get dark, and that game lasted one hour and thirty-two minutes. The umpires were in a rush. And Parmelee won his game 1–0. Pitching never had a better day than that.

Pitching today is ignored. It’s not ignored, but it’s a home run-hitter’s game, and that has lowered the quality of the game for me. They’ve brought in the fences, they’ve lowered the mound. The strike zone—you played ball as a kid?

Hank: Yeah.

Arnold: Shoulders to knees was the strike zone. Now it’s the size of a car.

Hank: I remember vividly as a kid when I was just starting to play baseball and starting to learn the game and watching it on TV, at that time letters to the knees was the strike zone I was taught.

Arnold: Okay, ours was shoulders to the knees.

Hank: I remember watching it on TV and seeing balls come across the chest and they were called balls, and it was confusing to me.

Arnold: It is confusing. I don’t know what goes on at umpire school, but what goes on is something that’s arcane. It’s a strange world where the strike zone is now like this. Wow! What pressure that puts on pitchers! Okay, so where were we?

Hank: Back to A Day in the Bleachers. I read something that you wrote recently for the LA Times. You wrote that you went to the game that day and it wasn’t until a few hours later after you got home that you thought you could write a book.

Arnold: Actually, I thought I could write a magazine article. I wrote a magazine article. I expanded the ballgame into ten thousand words. The only magazine that published stuff like that was The New Yorker. They would run important tennis matches, the whole match. John McPhee would cover it.

So I brought it down to The New Yorker and some kid came out. I said, “Here’s an article, it’s about a baseball game that took place, and if you publish it you’ll have to publish it right away.” The kid listened and he said, “Okay, I’ll have them read it.” He went upstairs, an hour later he comes back to me and says they liked it, but it wasn’t right. I took it home and I read it, and it wasn’t right. They were absolutely right that it wasn’t right. So I decided, what the hell, I’ll make it a book. So then I made it a book.

My agent Sterling Law thought it was wonderful and knew that Hiram Hayden over at Crown Publishing would publish it in a minute because Hiram Hayden was a Giants fan. Well, Hiram Hayden turned out to be a Cleveland fan, and he turned out to be absolutely right when he said, “I don’t know how to sell this book. There’s no place to sell it. If I put in the sports section, that’s where fathers go to buy books for little boys. If I put it in the nonfiction section it’s lost, it’s swallowed up. I cannot sell this book.” Colliers did not know that. They did not know the book couldn’t be sold until they published it and they found out that Hiram Hayden was right: It couldn’t be sold. It sold, as I tell people, like coldcakes.

We were driving across the country, we’d left New York in July of ’55, Bonnie and I and our daughter and our beagle puppy. We were going across the country and we got to Sioux City, Iowa, where Bonnie’s mother lives, and there’s a telegram from a friend of ours: “Congratulations, rave reviews in Times and Tribune, blah, blah, blah …” So suddenly I was famous, to twelve people.

Hank: One thing that I was thinking about as I was talking to a friend of mine this morning—you went to this game, just to go to a game. There’s a lot of luck involved here.

Arnold: I’m the luckiest fan in the history of the world. When I was a copy boy at the Daily News, I was sitting in the Ebbets Field press box when that ball got away from Mickey Owen. I won a limerick contest and I sat in right field and watched Don Larsen pitch his perfect game. Now, I had to be smart to write the limerick, but Larsen had been bombed in the previous outing in that Series, he could’ve been bombed again. It could’ve been an 11–9 ballgame.

I went with a bunch of kids to a football game in ’34–’35, the Giants against the Bears for the national championship. We sat in the lower left field seats, it was four degrees above zero, and we stood. We didn’t sit because it was so cold, and we shook our feet. The sound was like thunder. The Bears pushed the Giants all over the field in the first half, and Wellington Mara ordered an underling to go to Manhattan College and steal some basketball shoes. During halftime the Giants changed into sneakers and they pushed the Bears all over the field and they won 30–13. Now that game could’ve been any kind of game, but it turned out to be the Sneaker Game. I am lucky.

I go to a ballgame, it was Giants-Dodgers. It was Pee Wee Reese’s first time in the Polo Grounds. Mel Ott was on first base and they fed Reese for a force play and he went up in the air to throw to first for the double play and Ott hit him. Ott’s body was a horizontal blade, and he hit him right around the waist. Ott was not a fast man, but he was built like a small football player, and the cap went one way, the ball went one way, Reese went another way. Years later, I ran into Reese and asked if he still remembered the first game he played in the Polo Grounds. “Well, yeah,” he said. When Ott leveled you. He said, “It still hurts. I wonder why he did that.” I said I think he was saying “Welcome to the rivalry, Pee Wee.” And he said, “That’s what he was saying.” I was lucky that I was there to see that. So I have lucked my way through fandom. I’m the luckiest fan that ever lived. There are more but….

Hank: And didn’t you see Sandy Koufax’s first no-hitter as well?

Arnold: Bonnie and I. It was an anniversary. I went to the Dodgers and said, “Give me a couple freebies.” They sort of owed me. They winked because it was the Mets, they said they always sold out the Mets. I said, “Oh, you’ll make some room.” So we went there and Koufax pitched a no-hitter. Wow!

And of course, Willie Mays making his catch. That ball could’ve landed beyond him, or Wertz could’ve popped up.

Hank: So what about Willie Mays? What are your memories of watching him as a player?

Arnold: What are my memories of him? Watching him as a player, there was this wild exuberance in the beginning, that “Say, Hey” kind of quality, that gleeful quality that he brought to the field. And then that gradually disappeared as he got older and more mature and more serious about what was going on, and he realized that he wasn’t making the kind of money that he should’ve been making. He became an embittered young man and then an embittered old man. He remained, for the years that I saw him, the greatest player that I had ever seen for that period of time.

I saw him make some catches, not the Wertz catch, which was a good catch, it was not a great catch. He outran the ball, I mean that’s what it amounted to. In fact, I write in the book that he started to look over his shoulder and then thought better of it. I think what he did, he probably had great peripheral vision. He probably looked over his shoulder just to make sure the ball was where it should be. I think that’s what happened, now that I think back on it. I saw him make two other catches, maybe I described them elsewhere, one against Bobby Tolan…

Hank: I think you did.

Arnold: Anyway, he was great. He hates me.

Hank: Why is that?

Arnold: In ’64 I went back to cover the Phillies down the stretch. They were gonna win the pennant by ten games, that sort of thing. Sport magazine sent me to cover them for eight games, early in the month. Giants came in. Meanwhile I get a phone call from Doubleday, they want me to do a biography of Willie Mays, they’ll pay $250,000, which was then a lot of money. So I said to Willie—and at this time I think he wasn’t very happy with me because I had turned some of our magazine interviews into paperback books; but that’s okay, that happens—I said, “Doubleday wants me to do a biography of you.” Eyes glitter. I said, “They want to pay $250,000, and I’m guessing that’s their first offer, therefore I think we can go higher.” Glitter, glitter. And then he said to me, “90-10.” I said, “What?” He said, “Ninety for me, ten for you.” I said, Fifty-fifty, that’s the way it is.” “Not with me. With me, it’s 90-10.”

Charlie Einstein must have had one thing with him, maybe they did a 90-10, I don’t know. I said, “I’m sorry, Willie, it’s 50-50.” Later on, he ran into Al Silverman and he said, “Does that guy Hano still write for you?” Al said, yes. “Well, tell him to kiss my ass.” And then two or three years later he saw Al Silverman, he said, “Does that guy Hano still write for you?” And Al said, “Yes, he does.” His repertoire was limited. He said, “Well, tell him to kiss my ass.” It seemed that his anatomy and his cursing were limited.

So he doesn’t like me, but I think there’s good reason. He sees today what’s happened. He sees people in their first year of play, utility second basemen, who appear maybe thirty times in a season as baserunners, make $400,000 a year. He never made $400,000 in a year, even with throwing in all the commercials and everything else. I think that pisses him off.

But he was great. He played with a wonderful freedom. The only guy who came close to playing with that same sort of talent on the field was Roberto Clemente. He had that same … lacking the exuberance, he just happened to have the natural grace and ability that Mays had. I liked all those Latin ballplayers. Felipe Alou said on the phone to me, not long ago, “You did more for the Latin American ballplayer than anybody in baseball.” I wrote about them. I treated them as though they were human beings. I guess nobody else did.

Hank: I know from reading a Clemente biography a few years ago—David Maraniss’s book that came out about three or four years ago—he talked a lot about that, about how in the ’60s, the Latino players that were coming in, the press really treated them poorly.

Arnold: Terribly, terribly.

Hank: Made fun of them, made fun of their speech…

Arnold: Myron Cope, who’s a very good writer and a bright guy, he did that piece for Sports Illustrated. He said to Clemente, “How are you?” And Clemente went through this litany of things, so they ran a skeleton and they labeled all his injuries….

Hank: Yeah, yeah…

Arnold: Yeah, you remember that. Cope didn’t understand. Bonnie and I lived for a while in Costa Rica, we were in the Peace Corps. You and I pass on the street, we say, “Hi, how are you?” “Good, how are you?” “Fine.” Neither one of us means what we say, it’s a courtesy.

When you say to a Latino, “How are you?” they think you’re interested, and you stand still for thirty minutes because they go through from top to toe with a special interest in bowel movements. Cope did not realize it. When you ask Clemente how he feels, when Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh asked him how he felt when he got to the stadium and he would shrug and say, “Oh, my shoulder hurts,” he would scratch him. He’d say, well, I can’t play Clemente today, his shoulder’s hurting him. Well, everybody’s shoulder hurts in baseball.

Hank: But he didn’t know not to talk about it.

Arnold: He didn’t know not to talk about it. So I guess I didn’t do that. Cepeda loved me. He would bring me around and introduce me to Pagan and Marichal and those guys. They just loved me. And Alou did. I didn’t know that Alou has been married five times and has nine children. I didn’t know that. Ah, the things you learn. Anyway, what else?

Hank: After I read A Day in the Bleachers I jumped ahead a decade or two and read a lot of your Sport magazine profiles. I love to read about sports—I mean, I love to read in general—but I think I love to read because when I was a kid I read a lot of sports books.

Arnold: Sure.

Hank: And so I’ve read a lot of sports stuff, but what I read today is so different from what you were writing then. I was just wondering whom you read that influenced you.

Arnold: Well, don’t forget, I began reading Bill Heinz way back when he broke in, and he was one of the original “new journalism” sportswriters. Nobody even talks about that. But he would talk about it, he would find out what made a guy tick, they’d have a conversation, and then he’d repeat the conversation in print. And nobody did that. And he used the word “I.” So I read him, I read everybody. I read Tom Meany—Tom Meany did a biography of Babe Ruth and I liked it….

Hank: You quoted him in your Ruth piece, I remember that.

Arnold: And Meany would go around saying nice things about me as a result. Dick Young used to say nice things about me when he was doing stuff for the Daily News. He was a beat reporter. I didn’t really know him, I saw him around, but he would say nice things about me.

Heinz and I went together to cover the last day that Musial played with the Cardinals. He was doing it for Look, and I was doing it for Sport, so his piece would be coming out first. So I fed him things I had learned. When I went to Musial’s restaurant that night after the game, there was a guy, built a bit like you, and he waited the table and we talked. He had played ball with Musial as a kid. It added an extra little thing to the story, and I gave it to Heinz. He said, “You shouldn’t do that.” But his piece was coming out first.

Of course, I read everybody. I read Tom Wolfe, and I read Thomas Wolfe, and I read Hemingway, and I read Tolstoy. I read everything. I’m a reader. I have wet macular degeneration now and I can’t read. It is the great loss of my life. It’s very difficult for me to write. I’m trying to write a book on pitching because I want to do an antidote to home run hitting. I want to talk about it, I’ll even throw in my own bit about pitching. You know I pitched a little. Shall I tell you about my walk-on?

Hank: You tell me about anything that you want to tell me about.

Arnold: I was throwing a baseball around during lunch hour at LIU. A little factory in Brooklyn was where the campus was. A guy came up to me. I knew him by sight, he played on the varsity team. He said, “I’m gonna bring a glove tomorrow, would you throw to me?” I said, “Sure.” So he brought a glove the next day and I threw to him. And then I said to him, after about five or six pitches, “I wanna throw you a screwball.” And so I threw him a screwball and he went crazy, because it was a good one. He said, “You come out Saturday, I want to introduce you to the coach.”

So I went out Saturday. The coach, his name was Al Caruso, but he was only known as “All-American Al,” because Parade magazine or someplace had listed him as an Honorable Mention. They had done the first team, they had done the second team, and then there he was down there someplace. So we called him All-American Al or Triple-A.

So he looked me over. I was five-eleven, three quarters and two dimes by that time, I was just shy of six feet. Later on in the army I got run over by a truck, etc., etc., but anyway. So he grabbed a bat and he said, “Okay, Lefty, show me your best stuff.” So I threw him this screwball, and it happened to have been the best screwball I would ever throw in my entire life. It began a little bit around the waist, a little bit outside—on the plate but a little bit outside—but he lunged, and it broke, and he looked so … he looked terrible! He missed it by this much. And the guys behind me started to chatter. “Atta baby, Lefty! You got him, he’s your meat, Lefty!” So I threw him another one. I got this one up a little bit high, and it broke, and he hit a one-bouncer back to the box. I mean, a little tapper. I slapped it down with my bare hand. He came running out, he said, “Never do that! You’ll break your finger!” If he had hit it straight back to the box, I could’ve caught it with my teeth, it was so soft. Anyway, so I’m starting to throw the third ball, I’m 0 and 2 on this guy, and I’m trying to make the squad…

Hank: You have to strike him out.

Arnold: No, I think if I strike him out, if I do this again, he’s gonna come up to me and say, “You know, Lefty, you already have an academic scholarship, you’re gonna take space and we won’t be able to fill it with some kid coming out of Wilkes-Barre, blah, blah, blah …” He’ll make a reason. I don’t wanna embarrass him. So in the middle of my third windup, I threw him a fastball, and he hit it four hundred feet. And he ran around with a good baseball smirk on his face, and I made the squad! All I did was pitch batting practice, but, still, it’s a good story. All-American Al. So what else?

Hank: I had a question about Sport magazine in general. Were you assigned to things geographically? Because sometimes it appeared that you were.

Arnold: When I was back in New York I did whatever was around there. But when I was on the West Coast, you know, that’s an insular attitude. I was sent from Laguna Beach to Seattle to cover a basketball scandal at Seattle University!

Hank: Because it’s the West Coast, it’s all the West Coast.

Arnold: “Oh, Hano’s out there. He’s on the West Coast, he can do that.” They would never send anybody from New York to Cleveland, but this is a greater distance, much greater distance. So, yeah, you’re right. It was geographic. It was wonderful. There were very few well-known writers out here at that time.

Hank: I bet.

Arnold: You had some newspaper people. You had Charlie Einstein up there, me down here, down in this area. So I covered all the Dodgers, and I covered the Angels, and I covered the Giants, and I covered the Warriors when they were playing in San Francisco. The New York Times was as bad about it as anybody. They would send me to places…

Hank: So you were writing out here in the ’50s and ’60s. How did things change, I guess, in the “journalism game?” I know that in the East there were the Chipmunks, these young, college-educated guys.

Arnold: Al Silverman told me about that. I had never heard of these Chipmunks. You’re the second person that’s ever mentioned Chipmunks to me, but Al mentioned it. I didn’t know much about that. I thought we had some pretty good writers there. I thought that Roger Kahn was good, and Roger Angell was a wonderful writer. He didn’t do much for Sport, but he was a great writer. And Ed Lynn was a very good writer. So we had good writers back there. I don’t know.

Today’s writers are like Bill Plaschke doing his one-sentence paragraphs. Plaschke was invited to speak at the Festival of Books that the Times puts on with UCLA, but he had to cover a Lakers game up in Denver because it was getting to be that time of year, playoff time. The LA Times book editor called me and asked me whether I could fill in. So I filled in for Plaschke, and people were delighted because it was sort of a different kind of approach to the world. And I talked about what you and I are talking about, and it was good. It worked out very well as a result. I hope they invite me back again, this time for real and not as a sub.

I’m going to Tucson, SABR puts on a thing every year, and I’m the speaker this year. That’ll be fun. I guess it was different then. Sports Illustrated hasn’t changed much. They’re still flashy and splashy. They catered then to a yachting crowd.

Hank: More like a sporting life than a sports magazine.

Arnold: Yeah, yeah. But they did some wonderful pieces, wonderful people.

Hank: A lot of the things that you were writing about, whether you were writing about Deacon Jones or Lew Alcindor…

Arnold: He was the worst interview I ever did.

Hank: Why do say that? I mean, I would guess that, because that’s his reputation.

Arnold: He was, “No comment.” He showed up forty minutes late, he wouldn’t give me any time, he refused to engage me. I did my best, and I’m pretty good at getting people to engage. Impossible. Impossible.

Hank: You interviewed him when he was in college, right?

Arnold: Sophomore year. I was the first person to interview him. He was off-limits his freshman year, which was ridiculous. What are they doing? Anyway, sophomore year, I was allowed. But under all these watchful eyes. What was I going to do?

Hank: Now did you come across him later, did you ever have occasion to interview him again, or the desire?

Arnold: No, I didn’t, but he’s better. He’s improved considerably.

But I’ll tell you a funny story. I was speaking at some writers conference and there was a fairly good-looking, beautifully formed young woman sitting in the front row there. She’s eyeing me, and I’m going along, and she’s ogling me. And I’m thinking, “Oh, wow!” So when it’s over, I went up to her and said, “What was that all about?” She told me exactly what it was all about. She wanted Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s phone number because she wanted to lay him. She knew I had done a piece on him and a book on him, so I must know it. I said, “I don’t know that, and I don’t pimp for these guys anyway. But I said to her, “If I were in your place, and I wanted to do that, I would just find out where they travel and I’d meet him for breakfast one morning.” She did, and it worked.

Hank: It seemed like these pieces that you did, they were true profiles in the sense that they were more about the men than the games that they played or the numbers they had accrued.

Arnold: I hope.

Hank: So that was by design when you went in?

Arnold: Well, it was by design that I always want to know what you do and where you do it and what else do you do? In fact, editors were pretty good about that. If I would do a one-interview story you’ve done there and then I’d have to go and flesh it out. Today, it’s really like a thirty-second interview to me. Sound bites, is all it is.

Hank: It seems like if they’re doing a profile about someone, they talk to him, but it’s mostly about things that you already know.

Arnold: Or they find one thing that’s sort of hot. They’re friends with Tom Hanks and they go to the same bar. That sort of stuff. And they hit on that for the first ten minutes.

Hank: Another thing, going back to your writing style again: There was a time when journalists were taught to stay out of their own stories, but you’re clearly present in all your pieces, whether just as a witness or offering opinions about what’s going on. Why did you decide to do that? I love that.

Arnold: I think I began doing it when I was doing the first pieces that I did for TV Guide. Ray Robinson, who’s a very dear friend, asked me to do a piece years and years ago on Jayne Mansfield. I don’t do that kind of stuff. So he said, “How about one on Mickey Rooney?” I said, “Fine.” So I did a piece on Mickey Rooney. I found myself engaged with him and it worked well.

So then I did a piece on the actor Paul Douglas. You don’t remember the actor Paul Douglas. Anyway, he was very good. He had been a sports announcer and then an actor. Anyway, we had a couple drinks together, we went to his house together, it was loose. So I treated it loose, the way Tom Wolfe would have, or Hunter Thompson or people like that. I was influenced by New Journalism. I helped create New Journalism, but I was also influenced by New Journalism. Better than who, what, where, when, and why.

Hank: We talked a little about this with Kareem and your memories of that, but what makes for a good interview subject? How did you choose? Were they always assigned to you, or did you say, “Hey, I wanna go talk to this guy?”

Arnold: Usually assigned. Somebody like Al Silverman would say, “Do Bill Freehan.” Well, I didn’t know Bill Freehan from Bill Gates. I immerse myself in all the stuff I could find about the guy. I go to the library, I read all the clips, I talk to people so I know something going in. I write a query sheet. You have notes, I would have a whole query sheet. I don’t necessarily follow it, but I wanted to have it there as a backup. I want to know as much as I can about this guy and his life.

I’ll give you an example. Did you ever hear of the magazine Pageant?

Hank: No.

Arnold: Okay. Pageant was a Reader’s Digest-size magazine. Took no ads. It was the writers’ magazine, that writers loved. Ray worked there for a while, Ray Robinson. Ray asked me to do a piece on Robert Ryan, the actor. He said he’s the last liberal in Hollywood. To me, that’s about a paragraph. In two thousand words, that’s a paragraph.

So I went to see him. I did all the work before and I found out everything I could about him. So we’re talking, but we’re missing. And I said to him, “Bob, something’s going on. I’ve got you as heavyweight champion of Dartmouth College at the age of fifteen, and that doesn’t work.” He stopped and said, “My agent won’t let me be fifty years old. I’m fifty-three.” So he was being forty-nine for me, but his real age was fifty-three. And having said that, I guess he felt that I knew everything about him, so he started telling me about his drinking problem, and that became the story.

If you do enough homework, you often find something like that will happen. The story will change on you, and you change with it. It became a very good piece. He died a few months after the piece appeared. I was killing a lot of people for a while. Killing ’em off. John Wayne was an excellent interview, by the way. We’re one-eighty apart on almost everything, except that he not only was a great interview he also wrote nice letters back to me after the story would appear. Nobody does that. He did. Anyway, what were we talking about?

Hank: Something that you mentioned struck me. You talked about how doing a good interview changed you. How do you think you’ve been affected by interviewing all these people? Are there certain interviews, maybe, that stand out even after all these years?

Arnold: Some do. Bill Holden. He was making The Horse Soldiers with John Wayne and some woman. He said, “I’ll give you an hour between twelve and one.” At twelve I went to his dressing room and we started the kind of interview that we’ve been talking about. At five minutes to one I said, “I should tell you we have only five minutes left.” He said, “You know more about me than I do. Keep going.” So we went another two hours.

People don’t do that kind of work anymore when they do an interview. It’s on the spot. I will spend four or five days getting everything ready for that interview, for the major interview. Because I don’t think of it as an interview story, I think of it as a profile. A biography boiled down to two thousand words.

I did a story on Jackie Coogan, who had been the kid when he was four years old in a movie with Charlie Chaplin, and then he ended up as Uncle Fester in the Addams Family. Fifty years. His life was the history of Hollywood. And so I did this story. They wanted two thousand words. I wrote sixteen thousand words and then I started boiling it down and boiling it down and boiling it down. I got it down to twenty-four hundred words and I sent it in. I can’t cut another word of this. And they loved it. He told about how after World War II he couldn’t get any jobs anywhere. He went to the Charlie Chaplin studio—Chaplin had a studio then—and Chaplin was so delighted to see him, he replayed the movie The Kid, and he played the piano to supply the music, and they both cried.

It’s things like that, if you work hard enough you can get this sort of stuff out of people, but nobody works hard enough anymore. That’s a statement about society. This is a disposable society, a lazy, laid-back society, and that’s not how I grew up. My old man was out of work in 1934 for six months, and every day, seven days a week, he’d put his feet up on a wooden chair and he’d block his shoes, and he’d go out into that jungle. Every day for six months until he found a job. Today this is the bailout time. What else you got?

Hank: A lot of what I was reading was stuff that you had written in the ’60s, which was obviously a real turbulent time. You were writing about people who were kind of going against the establishment, whether it was someone like Bob Gibson or Joe Namath or whoever. How did you see the sporting world kind of reflecting what was going on in general society?

Arnold: I think exactly the way you described. I think there were the establishment folks and there were the anti-establishment folks. There’s Ron Fairly—he’ll do everything to please the boss—and there’s Bob Gibson, who won’t do a thing to please the boss. One makes a much better interview than the other, I discovered that. And it fits more with my attitude toward life. I don’t know which came first, but I’m a non-establishment person. As I get older I get more mellow, by the way, so I can’t even say that anymore.

Hank: There was one quote I wanted to read to you from A Day in the Bleachers. You were talking about Sal Maglie.

Arnold: Yeah.

Hank: He had been removed from the game and as he was walking off the people were cheering for him. And you were talking about how he had failed.

Arnold: And the best thing in life is failure.

Hank: Let me read it to you. “All the great people and great things in life are failures. It is in doing what we cannot do but must try to do that humans rise to their exalted fulfillment. Maglie had tried to do with an old man’s arm and back what a young man might not have been able to do as well. Of such failures is greatness made.”

Arnold: Yeah. I’d like to believe that. Whether I truly believe it or not, I don’t know. And I don’t think it’s fair to say that all great things in life are failures. I like to think that people should try more than they can accomplish and reach for the stars and then, if satisfied, grab a cloud and fly. I don’t think people try hard enough.

That’s certainly been true in the last eight years in this country and that administration. That was a laid-back, lousy, lewd eight years that we had. I think Obama’s gonna be okay. I think he’s gonna try. I hope he stiffens his back a little bit more than he’s doing. I think he’s gonna be okay. Thank you for quoting that. It’s a nice quote.

Hank: It was something that really jumped out at me when I read the book the first time. I think that sometimes you can learn more about yourself when you fail than when you succeed. I mentioned to you before that I’m a teacher, and I coach the basketball team at our school, also. I always think that I can give my players more when we lose than when we win. When we win, it’s just, “Good job.”

Arnold: Do you know Murray Kempton, the writer, at all? He was a New York Post writer. He covered the Don Larsen perfect game, but he covered it by talking only about Sal Maglie. Each inning he would describe what Maglie was doing. You know, Maglie went, again, eight innings. The same way. And this time he struck out the side in his last inning, but Larsen decided to pitch a perfect game that day. But it made for a wonderful column. So here’s a guy who fails in ’54, and then in ’56 he’s pitching an even better game against a better team…

Hank: On a bigger stage.

Arnold: People didn’t like Maglie. A lot of people discovered he was a very nice man, besides that snarling, hard-bitten, brush-’em-back kind of pitcher.

Hank: You know, it’s funny, because you talked about him very sympathetically, or heroically even. I always loved reading baseball biographies, and that’s a big reason why I’m a Yankees fan, because I read about Ruth and DiMaggio and Gehrig and all the rest. So Sal Maglie, in my head, was always the villain.

Arnold: The bad guy.

Hank: They talked about his thick beard and he was always the bad guy. So it was really interesting to read him cast in a different light.

Arnold: And then he joins the Dodgers. Carl Furrillo probably hated him more than anybody in the world, and he had to change his whole attitude toward him.

Hank: I don’t want to take up too much of your Sunday, but a couple of other things. We talked about A Day in the Bleachers, for instance, as being incredibly lucky that things kind of happened the way that they did. Do you feel like there are other things that you’ve written that people don’t know about that maybe we should? Maybe things didn’t break the way they should’ve.

Arnold: Well, I wrote the first Western novel with a black protagonist. Don Meade, when they received the manuscript, said, “We like this, and we’re gonna run it, and we’ll pay you your advance, but you’re gonna have to change the race of your protagonist because there are no black cowboys.” And I said, “Well, beginning with this book there will be one.” Grudgingly, and nicely, they okayed it. Then about a month before the book came out, a nonfiction work came out called The Black Cowboy. Turned out that seventy percent of all cowboys after the Civil War were black.

In that case I forced my hand. I’ve written some other things that people don’t know about because I wrote under a series of pseudonyms. I wrote a short story, a suspense story set far in the future, and it deals with book burning. Radio Free Europe broadcast it. It’s appeared in at least fifteen foreign languages, it’s been anthologized maybe twenty times. And that’s a short story other people don’t know about.

Hank: Is it under your name?

Arnold: It’s under the name Matthew Gant. It’s called “The Crate at Outpost 1.” When a library closed in south Laguna, they read this short story aloud because it has to do with book burning. Unbeknownst to them, the writer was present!

Hank: Did you raise your hand?

Arnold: Actually, I only heard about it from somebody. The writer was present in the town, but not in the building. When we went to the Alamo, I said to the librarian there, I said, “Do you have a copy of The Raven and the Sword, by Matthew Gant?” And she said, “Oh yeah, we have that.” I said, “I wrote it,” and they almost died. They brought it out and had me sign it.

So I’ve done some other things. And the fact that that “Mineral King” story was quoted in a Supreme Court decision, that’s good stuff. Very heady. A lawyer calls and says, “You’re part of a Supreme Court decision.” Wow. So anyway, I’ve had a wonderful and lucky life.

Hank: So as you look back on that wonderful and lucky life, you said to me early on that you didn’t think of yourself as a sportswriter but as a writer. What’s your legacy?

Arnold: My legacy here in town is that I worked my ass off to keep Laguna Beach Laguna Beach.

Hank: Oh yeah? Tell me about that.

Arnold: We have a low-profile town because of me. The city council back in 1970 wanted to pass a zoning law…

Hank: You’re talking about the height of the buildings?

Arnold: Right. To build a string of high-rise hotels from Broadway to Bluebird Canyon, about a mile and an eighth. A string of ten-story, hundred-foot-tall hotels. I started a movement against it and we brought out an initiative to make a building-height limit in the city of Laguna Beach so this could never happen again. We were the first city in America to use the initiative process to establish a city-wide building-height limit, and it passed. Thirty-six feet, three stories. Nothing ever taller will be built in Laguna, because of me. So that’s how they know me here.

And I write a column that appears in an environmental organization every month. I write a monthly column for them, and some of that stuff is as good as anything I’ve ever done. I don’t know,

Bonnie keeps saying I have to write out our obituaries so somebody will know what to publish. I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to write my obituary. I don’t want to close the door yet. If I ever get back to writing that pitching book, then I want to do another book about my brother who was killed in World War II. A book called, How Am I Doing, Big Brother?

Hank: Have you ever thought about writing your personal memoirs?

Arnold: I tried. At six hundred pages it was already much, much, much too meaty and much too long and not very good and I didn’t like it. It never went anywhere. I might figure out a way to do it in three hundred pages instead of six hundred pages.

I’m getting old. I’m getting tired.

[Photo Credit: AB]