I met Pete Dexter last fall when he was in New York promoting his seventh novel, Spooner. Dexter was a wonderful newspaper columnist and is now one of our greatest novelists. First thing I noticed about him was that he was wearing a pink Yankees cap. So when I had a chance to interview him the Yankees were the first thing we talked about.

Here is our chat, which covers a lot more than the Bombers.

Alex Belth: I had no idea you were a Yankees fan.

Pete Dexter: No, it’s true. I’m a big Yankees fan. It started out as a way to irritate Mrs. Dexter who is a Yankees fan from way back. And so when they’d win I’d get into it just because it irritated her so damn bad, but then I started to look at them and—

Alex: When was this, during the ’90s?

Pete: Yeah. So when I found out that it irritated Mrs. Dexter I did it more and more. There have been a lot of teams in my life that I’ve rooted against, but I have never rooted for a team in my life before I rooted for the Yankees, including teams I played on.

Alex: And the Yankees of all teams.

Pete: Yeah, strangely enough. I didn’t even like baseball until the mid ’90s. And I enjoy it more every year. We get all the games on cable. It’s the only thing that’s worth all the money I spend on cable.

Alex: So can you deal with Michael Kay?

Pete: Is he the “See Ya” guy?

Alex: Yup.

Pete: He’s okay, it’s the other two guys from ESPN that drive me crazy.

Alex: Joe Morgan and Jon Miller.

Pete: Jesus, they go on for hours and hours. Morgan was one of the most exciting players I ever saw and just absolutely the most boring human being on the face of the earth.

Alex: Just goes to show there’s no correlation.

Pete: Yeah, none at all.

Alex: So, did you want to be a writer when you were growing up?

Pete: No, never. I took two writing classes at the University of South Dakota, but it was just because I found out that I didn’t want to be a mathematician. I started looking through the student book there and saw Creative Writing and figured if I can’t bullshit my way through that then I don’t deserve to graduate, even from the University of South Dakota. But I never took it even semi-seriously. I mean, I didn’t read anything until… it’s a true story than when I wrote Deadwood [Dexter’s second novel], my brother Tom called me up and said, “You’ve now written a book longer than any book you’ve ever read.” And that was absolutely true. I stumbled into a newspaper office in Fort Lauderdale. I was 26 or 27 years old, and in those days you could actually stumble into a newspaper office and get hired as a reporter. But I don’t have to tell you what it’s like now.

Alex: Did you take to reporting pretty quickly or was it just another job?

Pete: I hated it. They had me doing—I thought it was a joke actually at first—they came over the first day and gave me a list of seven or eight things and said, “These are your beats.” And I thought it was some kind of initiation rite. You know, juvenile court, the hospital district, poverty programs, and tomatoes. There were agricultural products—tomatoes was a separate category. But there were literally seven or eight of them, none of which interested me even remotely.

Hell, they gave me a county health thing and there was a doctor who ran the county health department. He was a nice guy and I’d call him up every Sunday night when I came in and ask him if he could stretch something into an epidemic. And he’d say, “Well, we’ve got four cases of measles… you could call that an epidemic.” So every Monday I’d have a story in the paper about a new epidemic. The bigger paper down there was the Fort Lauderdale News. It got the big guy there fired because I kept coming up with new epidemics and he couldn’t come up with any.

Alex: Were you still a reporter when you got to Philadelphia?

Pete: I went to West Palm as a reporter and then became a kind of feature-writer sort of guy. And I didn’t like that very much. I liked it better, though, because they let me go do some things. I wasn’t sitting in meetings or pretending to. Then I came to the Philly Daily News as a reporter and that was going nowhere. And I was hard enough to have around and a new boss came in and he promoted a guy from within to be the new city editor and then made him the new managing editor/city editor.

Alex: This is Gil Spencer?

Pete: Yeah. And Spencer called me in… well, first the old city editor went in and tried to have me fired for insubordination and shit, and Spencer fired him. Then he called me in and gave me the column. And that was the first time I remember liking being a newspaper guy. And that was probably the best place to write a column in the world. They just left me completely alone. There was no kind of behavior that they wouldn’t tolerate.

Alex: So you didn’t have to write off the news then?

Pete: No. Just whatever was there, on my mind. Spencer and Zach Stalberg. You could work in the newspaper business for a thousand years and not find one editor that was as good as either one of those guys to work for, and I fell into it. I mean, I had to wait around for a year-and-a-half for it to happen. When Spencer left, Stalberg took over. And I was about through with it then, but you just couldn’t beat those guys.

Alex: Did they work closely with you on the text, line editing, or did they give you the freedom to do whatever you wanted to do?

Pete: Oh yeah… I’ve never had anybody text edit me in my life. [Laughs.] I probably should’ve. No, they just left me alone. And when things got way out of hand we’d have these little talks. Spencer… well, it’s like in Spooner, he’d lie on that couch with a white cloth over his eyes, smoking two cigarettes at once, setting the couch on fire.

I’m thinking now of the time with another columnist Larry Fields. Like the guy in the book that I first saw laying there on the sheet with a butcher knife. Fields had a radio show—you probably heard about this. He had a talk show and he invited me in. He’d been there about a month. I brought a bartender and some stuff to drink. And he’d been on one of those liquid protein diets for about three months and he’s a little-bitty guy and he’d blown up to about 220 pounds, not an ounce of muscle in his entire body. He’d gotten down to a 150 or something just by drinking liquid protein for months. And he had no tolerance for alcohol, it turned out. That was the night, amongst other things, Spencer was accused of having served time in Joliet State Prison for child molestation. It just went from there. We put a chair against the door so that they couldn’t come in and stop the program.

The next day Spencer pulls us into the office and he starts this big lecture and he just falls apart. He can’t do it. He was getting calls from Miami to fire both of us. He would never do it. And that’s the kind of guy he was. If you’d put a gun to his head that day and said, “You either fire Dexter and Fields or you’re gone, he’d say, ‘I’m gone.’ ” That’s just who he was. And you don’t find, especially now—Jesus, you would never find an editor like that. I met Ben Bradlee once and I thought he was an awfully nice guy and probably that kind of person that if you worked for him…

Alex: He’d go to bat for you no matter what.

Pete: Yeah. But I don’t think there’s very many of them.

Alex: What was it like for you when you started writing columns?

Pete: The size of it and the shape of it came naturally. I look back at the very early stuff and some of it is okay and some of it’s not. But I look back and see myself learning things as I was going along. It probably would have been a lot harder if someone was telling me, “You don’t want to do this, you don’t want to do that.” But like I said, I was left alone and pretty soon being left alone and finding out what people like and what they don’t and what I like and what I didn’t. It wasn’t hard, but the reason it wasn’t hard at first was because I didn’t have any idea of what was good and what was bad and then as I did start to realize it, it sort of… as it came to me what I wanted to do, I sort of did it.

Alex: Did you sense yourself building toward a novel while you were writing the column?

Pete: No. Nothing like that. I don’t have any long-range plans even now. I just always assumed what was going to happen. I’m not a fatalist or anything, but I just assumed things would go some interesting way. And they did. But there was no plan or anything.

Alex: So you never felt a desire to be a novelist?

Pete: No, not really. I’m sure it went through my head. Like everyone is always saying they want to do that, they sit around bars talking about it, “I’d like to write a novel.” I didn’t even do too much of that. The column was enough for a while. It made me really happy. Christ, it was so much fun. Like I said, I was being left alone. Then I did a little magazine stuff, enough to know that I didn’t want to do that.

Alex: Was this the stuff you did for Inside Sports?

Pete: Yeah. And Esquire and Playboy, I think.

Alex: Did fiction ever creep into your journalism? Because some of your columns almost read like short stories.

Pete: They were certainly framed like that. Nothing was ever made up whole cloth but the quotes and stuff… if someone said something to me and it could be said better by half, I’d clean it up, instead of writing the whole thing. I’d do that without any sense of guilt or anything.

To answer your question, yeah, I wasn’t exactly writing fiction, but I was using those techniques or some of the techniques that I know about now. I just felt like I was writing newspaper columns. I didn’t really know about newspaper columns until I came to Philadelphia. I never saw [Mike] Royko’s stuff or Jimmy Breslin’s or Pete Hamill’s or anybody, even when I was working in the Florida papers.

Alex: So you didn’t model yourself after any particular columnist?

Pete: I didn’t know about any of ’em. When I came to Philly there was a columnist named Tom Fox who went around saying he was the best columnist in America. Someone had once said that about him. There’s a lot of these guys. A guy like Royko didn’t brag, neither did Hamill. Breslin did, Tom Fox did. Fox wasn’t even the best columnist at our newspaper.

That was a guy named Larry McMullen, who was just starting out. He’d been a columnist for maybe two or three years when I got there and I noticed what he was doing. When he was good he was just telling stories, stories about South Philly. And he really was good. I’ve never seen a better fit for a columnist, a city, and a newspaper than Larry McMullen at the Philadelphia Daily News. I didn’t copy him or anything, but if anyone woke me up to the fact that this kind of writing was going on in the world, of what was possible, it was McMullen.

When I saw it, I immediately wanted to do that. And for a long time, or what seemed like a long time to me—it wasn’t really that long—it seemed that nobody was going to give me a shot at anything like that. I couldn’t stand the city editor. And there was just a series of guys, these ambitious cocksuckers that you find everywhere who don’t really know what they are doing. They’re everywhere. Those guys are generally—it’s part of their protective mechanism—they’re not going to give anybody with more talent than they have a shot at being something that they can’t control. They’re just not. On the few occasions that I went out and did something before I became a columnist… you always hear newspaper guys sitting around bars complaining about their leads being cut and shit, but they’d take a piece and cripple it and I guess they’d feel good about it without knowing what they had done. So there it was.

Alex: Did you ever feel constrained by the 800-count word count for a column?

Pete: No, because if I wanted to go 2,000 words, they’d run that. The 800-word column is a natural space for telling a little story.

Alex: So when you started God’s Pocket, your first novel—while you were recuperating from the fight you got into along with Tex Cobb down in South Philly—was it is a difficult adjustment, going from writing a column to a book? Did you just sit down and start writing or did you plan the novel and outline it?

Pete: No, God, I’ve never outlined a book in my life. You know, I had my brains scrambled pretty good and one of the results was that it changed the way things tasted for me. And one of those things was alcohol. I got to the point where I just couldn’t put it in my mouth. Pretty soon, as much time as I’d spent in bars, and as many great stories as I saw happen in bars, if you’re sitting there not drinking, by 11:00 it gets pretty old having sloppy people hanging on you. So I started writing about being in the gym more. Not that I was a barroom columnist, but on average there was one good, funny story a week in those bars.

But there was also one funny story a week at Rosati’s Gym, too. I can’t even remember deliberately starting a novel. I just remember one day before work playing around with it and the next thing I knew something was published and I’d read it and got horrified just before it came out. I thought it was way worse than it actually was. But I was like, “I just embarrassed myself.” It was nothing great, but it wasn’t anywhere near as bad as I thought. The harder one to do was Deadwood. The first one, you are not a novelist, just because you wrote one novel. But I set out deliberately to write the second one and had in mind that this is what I was going to do, for a little while anyway. All of a sudden I had to take it more seriously because I was going to spend the time. I’ve never had writer’s block or anything, but I took it more seriously the second time.

Alex: Did you feel like you hit a stride when you wrote Paris Trout?

Pete: No. There was no feeling from one book to another that I’d hit my stride. Something in me doesn’t think that way. None of the novels I’ve written matter. What matters is what I write today and tomorrow. When something’s done, it’s done. I’m removed from it. I have a real rooting interest in how the book sells and everything and how it’s treated critically, but the truth is I’m not with it anymore, it’s out there by itself. My focus is on the next thing. I just started writing a book about elephants, so that’s what I’m thinking about right now—elephants. I’m not thinking about Spooner. I’m not with Spooner anymore.

Alex: So did the success of Paris Trout get in your head at all, in terms of feeling pressure to have the next book meet a certain standard, either critically or financially?

Pete: It wasn’t that successful until it won a prize. What I couldn’t believe, they gave me the book award and the next year they gave the award to somebody else. I said, “Wait a minute.”

Alex: You thought you had the patent on it?

Pete: Well, I didn’t know. I couldn’t believe they gave it away. I didn’t say it was okay. The book did me some good economically. I couldn’t tell you in a hundred years what I got for Paris Trout, probably something like $35,000, I’m guessing. I know I got $8,000 for God’s Pocket, and Deadwood I did for so little that Random House felt guilty and gave me a little extra money when I turned it in.

After Paris Trout, after winning the National Book Award, all of sudden you are in a different world. Not that it’s independently rich money or anything but… I didn’t quit newspaper writing because of money, but at that point I could have. That was the first movie I ever wrote, too.

Alex: What was that like?

Pete: Strangely enough—I understood this right off—a movie and a novel are two entirely different things. There is no way for a novel to be accurately represented on the screen. That just can’t happen. You can make real good movies out of novels, but you can’t reproduce a novel. And I didn’t have to have that beaten over my head, I got that going in.

When an agent first called and asked, “How’d you feel about adapting your book for the screen?” I remember I said, “I’ll take the money, but I don’t know why they don’t just use the book.” I had some idea that they could just agree to a scene out of the book, memorize the lines in it, and go do it. I know it sounds kind of naïve, but I was a long, slow time coming into each one of these stages of a career writing—realizing what they involved.

The movie stuff still kind of surprises me. Essentially, a script is 120 pages, most of it white space, and the writing doesn’t really matter except for the dialogue. That’s the opposite of writing a novel. I knew writing the script wasn’t going to take as long as writing a book or be as much work.

Alex: Do you enjoy the process of writing a book?

Pete: No. But I did with Spooner and that’s the first time I can say that. Especially the last year. Most people who tell you that they love to write, right away that tells you that they can’t. Then there are people who like it some days and don’t like it others, there’s a chance for them. But if you’re doing it, it’s really hard. I mean, if you are doing it well, you’re occupying a part of your brain that doesn’t want to be occupied. The best lines that you write, at least sometimes, are the truest lines, and they’ll sometimes startle you when they come out. And to get at that place, where things are really true, is often uncomfortable. At least for me. Maybe if I’d lived a nicer life it wouldn’t be. And the work part is not like going into a room that’s too warm for three hours and I’m going to be uncomfortable in it. It’s finding your way there, for me. The hard part is the work part. And you have to do that again and again. You write two or three good sentences and then you have to get it all cranked up again.

Alex: Do you work in a linear fashion so that if you write a page one day, that you go over what you’ve written the next day before you continue?

Pete: Yeah.

Alex: And you don’t know where you’re going?

Pete: No. Once I get about two-thirds of the way through I’ll begin to sense it. I know there are writers who outline and there are a hundred ways to do it, so I’m not trying to say that my way is any better, but to me it’s kind of self-defeating to try and lead this thing around because the interesting thing about it is the characters and where they are taking you. There was a line that Padgett Powell suggested to me about the accidental nature of true things. That’s really true. And it’s not just the accidental nature of incidents but the accidental nature of true sentences and the accidental nature of true pages and chapters and books. And that doesn’t come if you try to work it all out ahead of time like you would with a movie script.

Alex: If you’re too deliberate you are hemming yourself in.

Pete: To me you should be letting it go where it wants to. I used to try and write movie scripts that way. Now you work on a movie and have a meeting with a studio head and tell him you don’t know what the story is going to be, but he should trust you. Well, you can get away with that for a little while, but then one of your scripts doesn’t get made for some reason, or somebody doesn’t like it for some reason, and word goes out, and then nobody wants to hear that. Especially these days, nobody wants to hear that. They don’t want to put all this money in and take a chance on that.

Alex: When you started Spooner, why did you choose to write a novel and not a memoir?

Pete: Well, first off, because I don’t like the whole memoir craze.

Alex: Too self-indulgent?

Pete: It’s self-indulgent and largely false. And the truth is I have huge gaps. I have no faith that I could write an accurate memoir. But more to the point, I wouldn’t want to. I’m just not a… I mean, I want to be able to write the story the way… and in a funny way, even though this Spooner character follows a lot of the things I did and goes to a lot of the places I did, I gave him some room. I let him do what he wanted to do. It’s not a memoir at all, it’s a novel. There is as much incorrect in there as there is correct.

Alex: In terms of how much he’s like you?

Pete: Yeah. Well, there’s a lot of things that happened to me that aren’t in Spooner and there are things in there that are intentionally not the way they happened to me. At the end of the day, this character Spooner is going to end up a lot like me, but the way we get there in real life and the way we get there in the novel are sometimes the same way and sometimes completely different.

Alex: One of the things that really struck me about the book is how much empathy you had for Spooner. For all the characters, really, but especially for Spooner. Was he a character that you particularly enjoyed?

Pete: You mean Spooner or Calmer?

Alex: Spooner.

Pete: Oh.

Alex: Calmer, I think, goes without saying. I think the affection that Spooner has for him and that you, as the writer, have for him, comes across vividly. But I also thought you presented Spooner with a great deal of empathy.

Pete: That’s true. I had a lot of empathy for Spooner and a lot of forgiveness for him. There was one other character named Charlie Utter in Deadwood that maybe spoke more directly for me, but Spooner ends up doing things and looking at things a lot the way I do.

Alex: He’s not self-reflective either. I thought it was interesting that Spooner has siblings who are so accomplished academically and he doesn’t seem to share their interests or talents in that regard, and yet he winds up as a writer.

Pete: That’s one of those places where if I was writing a biography or a memoir, that’s exactly true. Without ever setting out to, a series of circumstances presented themselves, to allow him to become a writer. And that was exactly how it happened for me. I was never any great self-starter or anything. I wasn’t going to be one of those guys who worked 70-hour weeks and then woke up a five o’clock in the morning to work on some secret novel. I never was that guy.

Alex: But you did have an ego enough to want to put yourself out there and do it.

Pete: I had something. Before I started the first novel I got a called from an agent in New York named Artie Pine, who wanted to represent me if I ever wrote something book length. He was a nice old guy. I ended up with his son, this little dickhead who thought he was important. I fired him for Deadwood. Well, I didn’t fire him exactly, I told him I did the negotiations for Deadwood myself and if he was going to be my agent I had to trust the guy and I didn’t. I said, “I’ll give you ten percent of what I got for this, but I want it understood you’re not my agent until I trust you.” He didn’t say anything. I went up to New York and told him this and then he sent me a letter saying he’d invested too much time and trouble and work in his career to put up with that from a first-time novelist. So, shit, that was great. I didn’t really have to fire him.

At any rate, it was his father who’d sent me a note about representing me, so I had a pretty good idea that if I did write a book somebody would publish it. And I hope that if I’d gotten halfway through it and realized I couldn’t do it, or that I couldn’t do it well, that I would have known enough to not do it at all.

Alex: In the afterword of Spooner you write about how much time you spent cutting stuff out. Was it really hard for you to make those choices and cut it down or was that actually enjoyable?

Pete: I didn’t dislike the process. Two hundred and fifty pages were cut and most of it was culling sections, cutting them down. There’s probably 50 pages I cut from the high school section, and 50 pages out of the Philadelphia section. I guess I did sort of enjoy it because as I was doing it I could see I was making it better, and that’s not always the case.

There are times I’ll spend a whole night re-writing and cutting stuff and the next day I’ll go in and look at it and could see I’ve uh… I might as well of just died a day earlier because this is worthless. But with Spooner, I had the whole book lying there and I had perspective. I knew where the story was going and what it was about. I always had the feeling that every day it was getting better. I did more than just tighten it. It’s the first book I’ve done where you can see the final version was really a full second draft. It was markedly different, certainly markedly shorter.

Alex: You also mentioned that you had a group of friends who read versions of the book. Is that something you do with each book or do you generally have a firm sense of what is working by yourself?

Pete: I give a copy to [former Esquire and SI senior editor] Rob Fleder because I really trust his instincts. The only thing wrong with Rob as a reader is, he’s such a good guy and an enthusiastic guy, and he’s such a decent human being, if I sent him something he didn’t like…

Alex: He’s too gentlemanly to tell you?

Pete: He would let me know in some way, but he wouldn’t let me know how bad it was. But I really trust his eye. He’s a really smart guy and a really good, experienced reader, and you don’t run into those too often. I trust him and listen to what he says. Of course, the book editor looks at it and I pay attention to that. My agent, Esther Newberg gets it.

Alex: What about Mrs. Dexter?

Pete: Mrs. Dexter doesn’t read anything until it comes out. But no, we don’t… I don’t have any idea what that would be like living with somebody who had some opinion of my work, a literary opinion.

Alex: That sounds like a relief in a way.

Pete: Yeah, if I asked her to do it, she’d do it, but it would be reluctantly. One of the nice things about Mrs. Dexter is that she has… I can’t say that she knows what she’s talking about. Nah, I can’t think of anything nice about her. [Laughs.]

Alex: Pete, you have this incredible eye for detail. Do you find that you notice things in daily life that you’ll later incorporate into something? Do you keep a note pad or scribble down observations?

Pete: No, but you do that unconsciously all the time and then when you are trying to draw something out it comes to you that way. And I think that’s better, too, because if you have some great image and great sentence in your mind you’re going to plug it in when it’s not time to do it. You’re going to plug it in when it doesn’t quite fit. That’s one of the things I learned early on writing columns. You don’t do that.

Alex: That requires a lot of discipline. I used to paint a lot and I remember I’d fall in love with a part of the painting but have to have the balls to paint over it if it wasn’t serving the picture as a whole.

Pete: Aw, shit, it kills you.

Alex: Murder your darlings, isn’t that the phrase?

Pete: I hadn’t heard that, but it’s true.

Alex: Since you’ve been primarily a novelist over the past 25-odd years, have you become a more voracious reader as well?

Pete: I’ve become more of a reader, yeah. I never was, and I’m still not voracious. But I read more now.

I’ve never really asked my brothers and sister about it specifically, but I can’t believe that as smart as they were that when they were fifteen, sixteen and required to read the classics they really understood what they meant. All of them have great memories and all of them were great students and everything, but I think there are some things that you just can’t understand when you are fifteen.

Alex: Ulysses wasn’t meant to be read by a high school or college kid, even.

Pete: Yeah, or…

Alex: A fifty-year old kid.

Pete: [Laughs.] Yeah, the second you said that I got a headache, right down the front of my head.

Alex: Have there been writers over the years that you’ve read and said, “Oh yeah, this is it, I really like this.”

Pete: The first person that I read and understood this is what writing is was Robert Frost. And then the first person I read in terms of reading everything somebody has ever written, and not only having read it but really understanding it and loving it, was Flannery O’Connor.

I’ve probably read all of Hemingway. I started in my thirties and my opinion never changed on that stuff and that was his short stories were awful good sometimes. I still think the novels are pretty much unreadable. I’ve read most of the twentieth-century Americans. probably. and a lot of contemporary people. I’ve poked around that stuff enough to know what it’s about and in some cases be really entertained by it.

Alex: When you are reading do you find that you are involved in the story first, or are you more absorbed by the craft of it all?

Pete: I want the story first, but if the craft is bad it’ll get in the way and pretty soon I’ll just put it aside, depending on how bad it is.

Alex: And what turns you off? Florid writing?

Pete: That and self-important stuff.

Alex: So are you of the school that the story is the most important thing and everything that gets in the way is just that, distraction.

Pete: Yeah, that’s true if the craft is part of the story. I don’t want to read somebody who goes on for 200 pages beautifully and at the end of 200 pages nothing has happened. I just don’t, whether it’s nonfiction writers or writers of fiction.

Then, there’s a guy like Richard Russo. About a year ago the New York Times called me and they wanted to know what was the best novel of the last 25 years. So I stared to think what I’ve really enjoyed. Entertainment is a really important part of a book for me and I was really entertained by Richard Russo’s Straight Man and Nobody’s Fool. All those novels. And there’s a guy—he really is a storyteller. He’s a very competent writer, don’t get me wrong, but he’s not… a great stylist. You are never going to confuse his stuff with Updike, but, on the other hand, he’s exactly good enough to carry those great stories and those great characters and that warmth that he has about the places and people that he writes about. He’s exactly good enough to do what he does and to me that’s the definition of what it is to be a serious writer. Which is to be good enough to talk about what you’re talking about without being so good that it’s all about your brilliance.

Alex: Showing off.

Pete: Right, exactly.

Alex: So the style is supposed to serve the story and not the other way around.

Pete: I think so. And if you start noticing style, you can sort of admire it, but if you’re stopping every now and then to look at a sentence—unless you are doing it because you love it so much—it gets in the way.

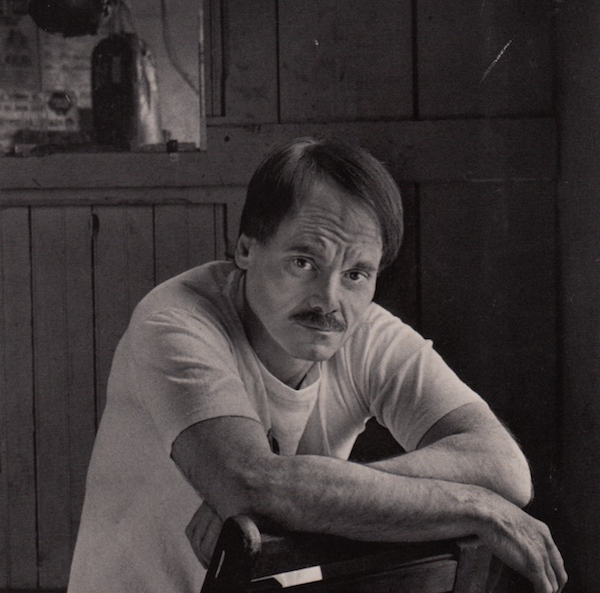

[Photo Credit: Marion Ettlinger, from the back cover of Dexter’s fourth novel, Brotherly Love]