“There are significant moments in the life of a human,” a significant man in Charleston, S.C., once told me. “Moments in our lives when we need to act right. It’s crucial that we recognize them when they come, that we gather the moment … or we spend the rest of our lives regretting it. A hurricane is a significant moment.”

I had never met a hurricane before, but I had this feeling that I might. The city I had moved to had met 90 of them in the last 300 years. Each time I jogged the streets of Charleston I would slow to a walk when I heard the clip-clop of the horse-drawn tourist carriages, feigning fatigue or retying a sneaker in order to eavesdrop on history. The guides spoke of the Great Hurricanes of 1699, 1728, 1752, 1804, 1893, 1911, spoke of wharves collapsing, church spires toppling, homes disintegrating, bodies being swept away by surges of water 10 feet high. I’d start jogging again, gazing up at the windows of the old houses, trying to imagine the significant moment.

One year ago, on the September day after Hurricane Hugo left Charleston behind, I looked around. There were barges and yachts in the streets, the roots of 100-year-old oaks in the air. There were pine trees in kitchens, dolphins in living rooms, restaurants in the sea. There were 13 people in the state dead. The significant moment. As dramatic as I’d ever imagined it.

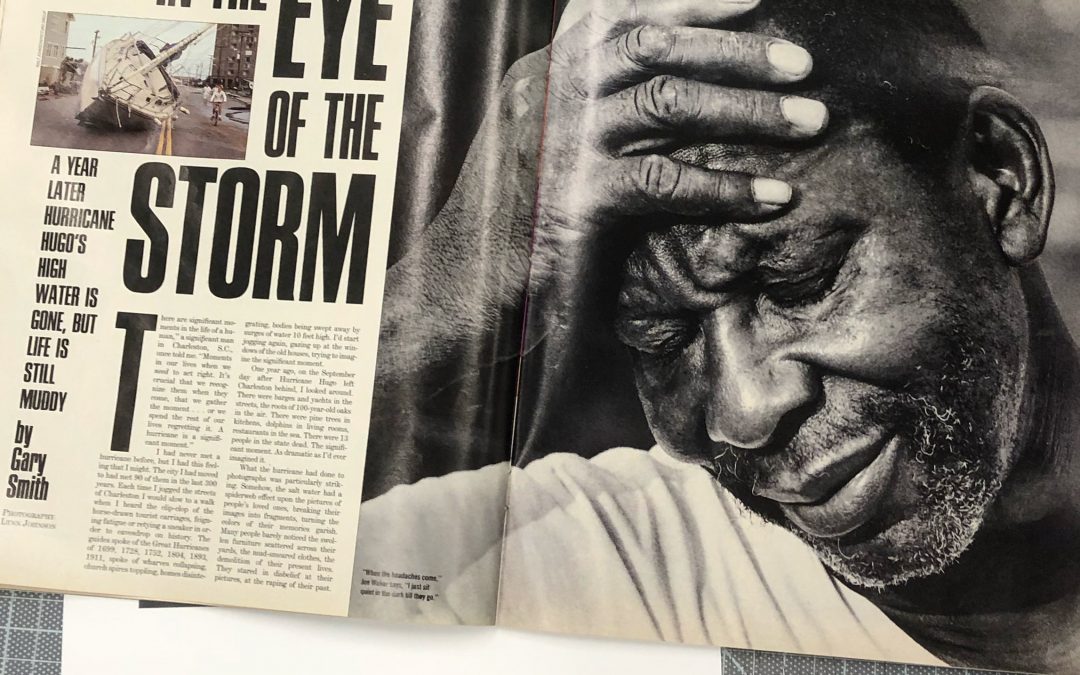

What the hurricane had done to photographs was particularly striking. Somehow, the salt water had a spiderweb effect upon the pictures of people’s loved ones, breaking their images into fragments, turning the colors of their memories garish. Many people barely noticed the swollen furniture scattered across their yards, the mud-smeared clothes, the demolition of their present lives. They stared in disbelief at their pictures, at the raping of their past.

But it wasn’t until nearly a year had passed, after most of the houses had been fixed and the debris cleaned away, that I began to understand the true nature of the significant moment. One day, as a man was showing me around his house—a home built high and strong enough that no floodwaters could invade his memories, his stacks of photo albums—he began to pause in front of the pictures he had hung on his walls and shake his head. It was nothing dramatic; I had to lean closer to see it. Slowly, patiently, moisture that had been trapped behind the glass since the storm was just beginning to do its work; a brown fuzz growing at the edges of the pictures was eating its way subtly toward the center.

The significant moment didn’t toll when church spires toppled, when buildings collapsed, when photographs turned grotesque. Behind glass and doors, it ticked on, more quietly than I’d ever imagined it.

The orphans. Joe Waker needed to find the orphans. His roof was gashed, his garage demolished, his two cars destroyed, his furniture ruined, his windows blown out, his floors covered with five inches of mud that kept making him slip and fall on his backside … and yet he couldn’t stop thinking of two children 9,000 miles away whom he hadn’t seen or heard from for 20 years.

It made no sense. They weren’t even children anymore. He didn’t even know their real names. But suddenly finding himself amid all these splintered homes and snapped-off trees and scavenging people, his mind couldn’t help itself; it just kept running back to 1968, to war, to the two orphans he’d found near Phu Vinh and taken care of for 10 months before his tour of duty ended. “It’s Nam all over again, that’s just what this is,” Joe kept saying. “Only thing missing’s the artillery shells.” He wondered if he should get on a plane, find the orphans. A crazy idea, with all the misery right here in front of him; he knew that. But he should’ve done more for those kids than sneak them C rations and pay a woman each month to take care of them. He didn’t quite know what, and it didn’t matter that he and his wife had since helped raise six foster children. It was just this feeling he’d had ever since the sky went berserk. He wasn’t a good enough man.

I’d met Joe Waker only five minutes before, but that’s what hurricanes do to people—you could pull your car into a stranger’s front yard and he’d start talking to you straight from his gut. “I’m ashamed,” he said. “I give my disability check to my church each month, but I should do more for people, I’ve got to do more. Why aren’t all of us doing more? A month ago I had $50,000. Now I’m a poor man—in a couple of hours I ended up like a wino. If I’d given that $50,000 to people who needed it before the storm, I’d still be poor now, so what was the point of keeping it? Why did I have a second car? Tell me so I can tell you.

“We deserved this storm. We forgot we needed each other; we spread to the four corners like a covey of doves. But I’ve been woken up. I’ll change. You wait and see—seventy percent of the people in this area are gonna change. I’ll open my house, teach kids how to do carpentry. Free. When that water was rising, that’s all I could think of, all the things I could’ve done.”

When that water was rising it sounded like this—voop, voop, voop—oozing up through the floor, climbing over their ankles. “Slimy stinkin’ stuff, Lord have mercy!” Joe’s wife cried. First the roar of the wind sounded like a hailstorm without any hail and then like a freight train running through his backyard and then the water was knocking over tables and oil lamps and in the chaotic darkness Joe Waker had three lives to save. There was an 84-year-old woman that he’d invited in, his 68-year-old sister with heart trouble and his 54-year-old wife with leg trouble, the latter two each weighing more than 200 pounds. Joe peered out into the night. The headlights of his two cars were on, the headlights were moving, the horns were blaring. Who in God’s name was out stealing cars in this? “Don’t panic!” shouted Joe. “We’re not gonna stay in here and get trapped. Everybody stand near the porch!” Now the water was up to their waists and Joe was beating away the snakes with a stick and the salt water was making the cars’ lights and horns go crazy and one car was ramming the garage and the garage was collapsing and trees were crashing and tin roofs were flying and butane gas was hissing and a dog nobody had ever seen before was clawing his way out of the water up onto the patio sofa on the porch. “Jump back in that water and drown!” Doris screamed at the dog. “You don’t have a soul to save!”

Should’ve done more, man, you’re running out of time, you’re just not good enough—that’s what the hurricane had howled to him.

Joe’s mind raced. He yanked on the rope and bed sheets that he’d tied to the porch pillars, to make sure they would hold. In a moment he was going to harness the sheets around the women’s chests, get them up on the mattresses he’d bound together with rope and then let the rising water lift the mattresses up onto the roof. Almost like Nam, that day the monsoon floods came and he’d lashed himself to a bridge with a rope and grabbed a child floating by and held on for dear life, watching, helpless, as scores of other children went howling by.

When the water reached the women’s armpits, it stopped rising. Just like that, stopped, like it all had been a joke. A few hours later the sun came up. They had no flood insurance. Even their false teeth were gone.

Joe stepped outside. His 91-year-old mother’s house, empty since she’d died of a stroke nine months earlier, was still there, just a few feet from his house. But now all the things he’d refused to look at since her death—the quilt she’d spent three winters sewing, her slippers, her knickknacks, her bras, her life—were scattered in the mud, across his yard. He felt something climbing up his throat. So it was true. His mother was dead. Joe Waker, too, was an orphan. He used his gums to bite the feeling back.

Doris went away to stay with a friend. When she pulled back into the driveway two days later and called, “How you doin’, Joe Waker?” it caught him by surprise; his gums, they just weren’t quick enough. “Here’s flesh!” Joe cried. He buried his white-flecked beard into her neck, squeezed her and burst into tears. “I love you, honey. Ohhhhh, I got flesh!”

Doris stepped back. For the first time in 22 years of marriage, Joe had declared his love. “Wish I had a tape recorder,” she said. But that, too, had been washed away by the storm.

On the morning after in McClellanville—the town just north of Charleston that Joe Waker lived on the edge of—the people moved through knee-deep water, slowly, as if they’d all been struck by a fist. The people hugged, then broke their hugs, bent down and smacked the fish that were biting at their ankles. Word began to spread: Graves had “popped” during the night, the earth had belched up the dead. Nellie Garrett’s dead son had floated right up to her door. It was a lie, of course. The coffin never made it quite as far as her door.

A thought chilled Joe. What if Mama had popped? He jumped into his truck, drove to her grave in Moss Swamp, made sure she was snug. “Good thing you were already gone,” he whispered to her. “God worked nice—don’t think I could’ve saved you. But don’t you worry none about me, Mama, I’m a survivor.”

No electricity. No telephone. No drinkable water. No dry place to sleep. Against that, a man who had earned Bronze and Silver Stars during 20 years in the Army building roads and airstrips, who had retired as sergeant first-class and then graduated from a four-year college as a master carpenter and plumber, he knew what to do, but where to start? He grabbed a hammer. He heard a hoot. He turned around. Joe-Joe?

The son he left behind 22 years ago, when the boy was six, when Joe’s first marriage fell apart—like a vision, handsome and hard-muscled, pulling into the front yard, all the way from Washington, D.C.—there he was. Hauling a car for Doris to drive, hauling tools and food and batteries and hope. The three of them looked at the rubble and felt bad. They looked at each other and felt good. A hurricane was a funny thing; it could make everything dirty, wipe everything clean. “Hugo’s binded us,” said Doris.

Each of them had plans. When they stepped away from one another, Joe-Joe said: ‘I’m not gonna let him work. My dad’s fifty-four, but his body’s older than that from all those years in the military. He’s lost half his stomach to ulcers. He’s too old for this. I’ll do the work for him. That’s my mission here—to keep my daddy retired.”

And Joe said: “Retirement’s over. I’ve woken up.”

And Doris said: “Can’t feel right till this mess is cleaned up. I just want to get back to normal.”

And Joe said: “Normal’s no good. When things are normal, we forget each other. Leave the junk. I can live like this till the day I die.”

A month passed. The electricity returned. Joe-Joe got tired of seeing his dead grandmother’s life in the yard and began carting it to the dump. Joe followed him to the dump and began carting it back. “He’s young,” said Joe. “He doesn’t understand.”

Joe and his son fixed up the Waker house just enough to live in, then abandoned it. They spread out through the neighborhood, ripping reams of sodden Sheetrock from widows’ homes, installing plumbing for husbandless mothers, laying down new floors and roofs. Joe Waker charged some people nothing—Joe-Joe could only shake his head—others, he charged only half- price.

Doris couldn’t bear to stay at home. Outside were piles of pink insulation, chairs, pipes, underwear, hangers, paint cans, shingles, albums, books and God knows what else spread across the yard, everything powdered with the lime Joe had spread to kill bacteria. Inside was worse, every room a wreck, all the appliances ruined by rust and salt. She’d do volunteer work, she’d go to the little hair salon she owned and work there rather than stay in that war zone of a house. Each morning she’d wake up vowing to stay calm, to be strong, to begin buying the furniture, lamps, curtains, rugs, clothes, refrigerator, washer and dryer she needed. She’d wedge through the hallway where the mattresses were stacked, maneuver around suitcases, disinfectants, pots and pans, then get in the car, pull away and find herself staring at the national forest that lined the highway for miles. The forest once green and cool and soothing, now a shattered, leafless wasteland, three of every four big trees lying on the ground. She’d walk into a furniture store, waiting for the joy to come over her that she felt when she decorated her house as a bride. Blankly she’d stare at all the shiny new things, then feel herself becoming nauseous, like a pregnant woman. “Would you walk away for a minute?” she’d ask the salesman, then lower herself onto a showroom sofa and cry.

There was no escape. Back home, she drew bathwater and couldn’t step into it. That night came back; clean water felt dirty. She tried a shower instead and had to bite her bottom lip to keep from screaming. She tried telephoning her friends, but after a word or two, the line would go dead. She sat down to eat, but one look at food made her sick. Finally she turned to her last resort, her surest refuge: She had sat with her Bible on the toilet just before bed for years. This time she only lasted a minute, then the rusted bathtub and the mud-filled vanity with the door ripped off drove her away. “Joe,” she said, “I feel like the bottom’s falling out.” She sagged into her favorite rocking chair. The bottom fell out.

She dragged herself up by the armrests. “I can’t live like this, Joe. Is it just me, or is it doing it to you too?”

“Storm didn’t affect me none,” Joe had taken to saying, “been through Nam twice, been to Korea.”

“Nobody had to look at this house in Vietnam,” said Doris. “You’re never here, you’re not facing up to it.”

She didn’t know: Joe had found a refuge. Ever since the hurricane he had been waking up for no reason at all at one or two a.m., slipping out of bed, climbing into his truck and standing beneath the moon at his mother’s grave.

Should’ve done more, man, you’re running out of time, you’re just not good enough—that’s what the hurricane had howled to him.

Done just fine, boy, done all a fella could—that’s what his mother’s bones whispered. She was the only person in his life he’d held nothing back on, he’d done everything for. Built her house, plowed her vegetable garden, cooked her grits with cheese on top. Sat with her without his eyes jumping and his feet edging toward his truck, the way they did with everyone else. And now it was only to her that he could run in the night.

“This hurricane didn’t wake people up. Next time God’s not gonna take trees—he’s gonna take bodies.”

It was November, seven weeks after the hurricane. Joe was on a roof with a hammer, waving to every other car and truck that passed by. This was how he preferred his friendships—hellos and goodbyes from 50 feet away at 50 miles an hour. He was knocking out the jobs one after the next, taking three or four short breaks a day to sneak in hellos with his grandchildren a few miles away. They had seen him only once or twice a month before the storm. “I’m rollin’ like a big wheel out of the cotton fields of Georgia!” he crowed to his son.

Joe-Joe looked at his dad, shook his head and then nudged him aside. Joe-Joe had hidden the truck keys once, chilled the old man out for a few hours, but his plan wasn’t working, he couldn’t keep his father from fixing. The other night Joe-Joe had found him sitting on the hearth with his head buried in his hands. Nobody ever saw Joe Waker do that.

“Don’t do it like that,” the young man said. In a minute the father and son were shouting. In another minute Joe was slamming his truck door, heading home. “Mission accomplished,” said Joe-Joe.

Joe Waker stiff-legged his way to his door. The arthritis in his left leg was beginning to ache so badly he often had to use his hands to drag the leg in and out of his truck. His head ached. No wife at home, no dinner cooking, no dishes clean. “Gotta do everything around here,” he mumbled. He took a deep breath. He wouldn’t snarl at Doris when she came home; he was stronger than she was. He’d been blinded for a week when an artillery shell exploded a few feet away in Vietnam. He’d been a prisoner of war, he’d escaped.

While Joe ate dinner alone, Doris slowly rose to her feet in front of a few hundred people who had gathered at her church to discuss posthurricane stress. Her bottom jaw shook. While talking on the phone that day, she’d had to hold her chin with her hand to stop her teeth from chattering, but she couldn’t do that here in church. “Each time it rains,” she told the gathering, “I have to get up and look outside to see if the water’s coming again. I feel like I’m choking. I feel like there’s been a death. I feel like I’m going crazy.” She started sobbing. The women sitting near her rubbed her back. The man leading the discussion told her that it was good she could talk and cry about it, that even God’s people got scared and depressed. “You telling me I’m normal?” Doris asked through tears. “You telling me I’m gonna make it?”

December came. Change rippled through everything that lived around Joe and Doris, the backwash of a hurricane. The crime rate jumped. The psychiatric wards filled. The number of women conceiving babies nearly doubled. The roads filled with strangers, hard men in out-of-state pickup trucks who were looking for work. Insects bit more people than ever, trees with no leaves blossomed in winter.

These were the kinds of stories they told on the evening news. But Doris and Joe’s story was the other kind, little spoken of or noticed, mildew in the human soul. Two people who cared about each other but couldn’t quite articulate what was happening because they didn’t understand it themselves.

The half of a stomach Joe had left was beginning to bother him. His face, which sawdust and sweat made burn and itch madly ever since its exposure to chemical defoliants in Vietnam, kept getting more sawdust and sweat on it each day. He’d start to fix a wall or a cabinet at home, but it didn’t make him feel what he felt when he did it for someone else. It was all becoming so complicated, turning into a question of manhood, of independence, control. Any minute now Doris was going to ask him when he was going to do something about the den and he was going to growl, “Hire somebody else,” and she was going to grow hurt and quiet and he was going to reach over and touch the back of her hand and wonder if he’d gone too far. Or someone else was going to come to his door with his hands in his pockets and his eyes on the dirt and ask Joe to fix his house, and Joe was going to grumble for a minute or two, so nobody would take him for a sucker, then end up saying yes.

The only way to avoid them all was to hop into his truck and head for the dirt roads. He would park by a wooden bridge, read the Bible or just sit and stare at the fields where he used to pick blackberries as a boy. Strange, but more and more since the storm he could almost see that little boy with the bare calves poking out of his ratty pants, with the fertilizer bag full of firewood slung over his shoulder so he and his mother wouldn’t freeze. That little boy without a dad, wearing newspaper for socks, and nails and a wire to hold together his shoes, the poorest of the poor, the one the blacks called Black Joe. Look how fast he walked, afraid the boys would surround him and taunt him, afraid that one would sneak up on all fours behind his knees so another could give a little shove and send him toppling. Hurry, boy, hurry home and grab that rifle again that you hid in the garden, the .22 you pulled the trigger on 16 times when you couldn’t stand it anymore. Scattered ’em like flies—never bothered you much after that, did they?

At 17 he had entered the Army on an impulse and vanished for six years, gathering himself, gathering his money, just waiting. Then one day he simply appeared in the old neighborhood in a brand-new Chevy and a fine set of clothes, and he knocked on the door of every man who had taunted or ignored him, every woman who had looked into his hungry eyes and refused him bread. And he smiled and offered each of them a ride. When he dropped them off, he very politely would say, “Here I am, same Black Joe you said would be nothin’ … and I just gave you a ride.” So sweet, it felt, but never quite sweet enough, because a few years later, in a bigger and shinier car, he had to come back and do it again, and he had to move back when he got out of the Army. He always knew that they would really need him for something someday, something bigger than a ride in a shiny new car, and when that day came, he would have the ultimate revenge—he’d help them! And now that day had come, and Joe Waker couldn’t let it go. “Don’t you think their consciences bother them now?” he cried. “I’m evening the score. I’m proving my point. I’m helping them. Never forget this: When you feed a person with a silver spoon, it’s worse on them than violence.”

Christmas came and left: No one smelled it at Joe Waker’s house, no one heard it. They called no family or friends; no family or friends called them. Their phone line, rarely working since the storm, was dead again. Death teemed in the rank soil around them. In quick succession, Doris’s nephew was murdered, her cousin died, a neighbor died, Joe’s cousin died, his brother’s brother-in-law died, and one of his best friends, who had given them a dozen bags of clothing right after the storm, was shot dead. Now it wasn’t just junk in the house, it was spooky junk. Doris packed the dead man’s clothes into the car and gave them away. “People dropping like flies,” muttered Joe. “Death starts rubbing off on you.” Since the storm, he had lost 14 pounds.

Eight days into January, as he sat in his truck at an intersection, he looked to his left. A dump truck was coming right at him. He pressed the accelerator to pull onto the highway and evade the dump truck, caught a glimpse of a tractor trailer barreling down the highway a few feet away, jammed the brakes and took the hit from the dump truck. Pain shot through his shoulder; he blacked out. Joe-Joe brought him home from the hospital with his left arm in a sling. “I’ve got to slow down,” said Joe. “Things are happening too fast. Why keep pushing myself, anyway? People only take advantage of me. I’m on somebody’s roof fixing it for half-price, and he’s watching me in $125 sneakers and $75 jeans. This hurricane didn’t wake people up. Next time God’s not gonna take trees—he’s gonna take bodies.”

A few days passed. Off came the sling. Off went Joe Waker to work. Both Doris’s fists slammed the kitchen table. “One room!” she cried. “If he’d just finish one room.”

March came. Joe dipped into the bottom of his savings. Doris drove up to the house in a new white Cadillac. Inside the house, the living and dining rooms had new carpets and furniture. “Actually enjoyed shopping for it,” said Doris. “Know what my girlfriend said to me? ‘Thank God, girl. Hugo’s finally leavin’ your face.’ ”

Joe-Joe sat outside on the steps, in a dark mood. After six months here, longer than he’d ever dreamed of staying, he was packing to leave. He’d wrung all he could from this hurricane—a chance to help his dad, to reestablish their relationship, to get one last taste of freedom before he got married—but it hadn’t quite worked out. He hadn’t slowed the old man down any, didn’t feel any closer to him. They were both too headstrong, too leery of closeness, both too much the same. “My father expected me to be the same little boy I was when he left home all those years ago, the one who listened to everything he said, and it couldn’t be,” said Joe-Joe. “I’m a man now. The more I’m around him, the less I understand him. It’s easier for my father to help people he doesn’t know than ones he’s close with.”

One afternoon not long after that, Doris walked through the front door, saw a body sleeping on the sofa and jumped. It was her husband. “Never seen that before,” she said. “Something’s wrong with you.”

“Tired,” said Joe.

“So tired …”

March gave way to April, April to May. Now Joe’s stomach burned like someone was pouring hot coffee right down the pipe, now his headaches pounded harder and more often. He flashed hot and cold, broke out in sweats, came home clutching fistfuls of medicine that he wouldn’t explain to his wife. He began laying down his hammer at midday, driving home and dropping into bed. He felt so bad one evening that he began telling Doris who owed him money and what the money should go toward. All through the night, Doris poked him and said, “You all right?” She didn’t want to wake up beside a dead man.

One day, when summer drew near, Joe stood in the woods he’d once foraged for kindling. Maybe he’d misinterpreted the howl, maybe he’d gotten the message of the hurricane wrong. “I can’t keep doing it,” he said. “It grinds you to dust. Used to carry Sheetrock half a mile, a sheet of plywood up a ladder. But I can’t do it anymore. That’s what the hurricane taught me: I’ve become an old man.”

June came. Humming gospel music, Doris walked through her nearly finished house, settled onto her new living room couch and gazed at her new picture—a painting of a seagull flying over an ocean, winging away from dark sky and heaving waves and winging toward the sunlight and calm.

On the TV in the den, a man was reporting that the new hurricane season had begun. Joe’s eyelids sagged; he barely heard it. He was still in the eye of the old one.

You’re living in a house your great-great-great-great-great-granddaddy built in 1796, longest-running father-to-son continuum of any house in the city, one of the longest in all of America. A Category Four hurricane’s coming with 135-mile-an-hour winds and a tidal surge that could run from five to 20 feet. They’re sandbagging city hall next door. Do you stay—or do you leave?

The house is three stories tall, 5,200 square feet, brick walls that have survived tornado, hurricane, earthquake and bombardment from Yankee cannons, a home that one family has clung to through the collapse of cotton, the disintegration of the old South and the Great Depression. Your kids are seven, five and three. The mayor’s urging everyone to leave, the highway’s jammed with evacuees. Do you stay—or do you leave?

Dan Ravenel looks up at the sky, looks up at his home. Six generations of eyes looking over his shoulder, six generations of Ravenel sacrifices to protect. It’s not his house, it’s his son’s house and his son’s son’s house. He’s staying.

“This house is a fortress,” Dan’s thinking. “It’ll be what’s standing after nuclear war.” He’s Daniel Ravenel the Ninth but not a Daniel the Ninth kind at all, a 40-year-old owner of a real estate company who cracks jokes to his clients, waves to everyone in town. He secures the 42 windows with wire, nails, shutters and plywood. The wind begins to blow.

It’s 10:30 p.m. The windowpanes are bulging. The noise is deafening. The dog’s going nuts. The blood’s gone from his wife Linda’s face. She and the three kids look up at him from under the dining room table. A window shatters, then another. Off runs Dan with hammer, nails and plywood. Every room he runs through groans with pain and whispers with memories. Through the master bedroom he goes, where in the early 1970s he watched his mom and dad slowly die. Through the hallway where Daniel the Second, too old in 1800 to travel to his plantation, pulled back the rug and chalked out a map of his land on the floor with instructions for his servant to memorize; where five-year-old Daniel the Tenth, nearly two centuries later, often plays with his GI Joe. Down to the library, where in 1819 Henry Ravenel sketched maps of South Carolina that would become the first atlas ever of an American state; where in 1962, as a 14-year-old, Dan snitched sips of the mixed drinks he served to his father’s friends.

It’s 11:30. The wind’s hurling dirt through the walls, mortar’s crashing down the fireplace. Part of the largest elm tree in the city crashes through the window on the landing between the first and the second floors. Off runs Dan. Three-year-old Ruthie’s screaming, “Mommy, Mommy!” Seven-year-old Elizabeth’s terrified that the dog’s going to die, and Linda’s holding them all under the table, thinking, “Oh, God, we blew it. We never should’ve stayed. We blew it.”

Dan puts his shoulder to the limb, shoves it out of the house, boards up the hole, races downstairs to check on his family. Children have been born in this house, children have died in this house—please, God, not now. Another window blows out on the third floor. “Don’t leave!” Linda cries. “Don’t worry about the house. Stay with us!” Off runs Dan. It’s not for Daniel the Second or Fourth or Sixth or Eighth anymore; he has to save the house now so the house can save his family. Ka-boom! Just behind his shoulder, another tree limb explodes through the closet of a third-floor bedroom. The whole house shudders. “Are you alive?” Linda shouts up the stairs. “Come down, Dan. Forget the house!”

It will take nearly two years to repair the Ravenel home. The family will have to move into the backyard carriage house. But in the end, none of that will really matter. Daniel the Tenth has watched Daniel the Ninth. His turn will come. He’ll be staying.

Might as well be a canning factory—that’s what Dan Dyer used to say about working in a hospital. He was a 29-year-old man who always had a Chevy truck or a Miller beer cap tugged over his head, tattoos of Yosemite Sam and Donald Duck on his arms and a short, beefy body born to do what he did: operate a boiler room. He sent up the steam that sterilized the surgeons’ scalpels, the hot water that washed the patients’ bed sheets, the cool air that kept the nurses from getting grouchy in summer, and yet none of them—even the ones who had worked at Roper Hospital in Charleston all eight years that he had—had a clue that he existed.

“Somebody has to do this job,” he would shrug and say. “Might as well be me.” But it gnawed at him sometimes, knowing that his labor was essential to the life-and-death dramas occurring on the floors above him but never being able to see or hear or feel it. Now and then he had an urge to follow the steam and the hot water upstairs to see all the babies it helped birth, all the people it helped keep alive. But no one wanted him up there. Only for his paycheck did he go up, staying just long enough to notice that some of the nurses weren’t hard to look at, and then the elevator doors would shut and it was back down to the pipes and valves and steam.

Then one night Hurricane Hugo came—and the electricity went out. Roper Hospital shifted to its backup system—five generators in the boiler room—but then the pump that drives the diesel fuel from the outside tank to the generators went dead too. Someone would have to go out into that insane night and crank the pump by hand or darkness would fall over 448 beds and panic might break loose in the intensive-care unit where 14 people clung to life.

“I’ll go,” said Dan. Clutching a rope, ducking, cringing, he threw himself into the wind and water that rushed through the 30-foot-wide alley separating the boiler room from the holding tank. Bricks and shingles and sheets of plywood flew past his head, fragments of floating docks rushed by in the waist-deep water. Crouching by the tank, he cranked the pump until the boys in the boiler room gave him the full signal. Then he made his way back through the frenzy to catch his breath—until the next trip.

By the third trip his arm ached from cranking and the horror of what he was risking had sunk in. He felt the 4,000-gallon tank trembling as if it were about to burst or topple upon him, pictured the huge cooling towers perched atop the boiler room crashing down. A colleague, David Johns, joined him. Dan did it five more times, then lay on the concrete floor on a pillow of rags.

“Hey,” someone called to him when the sun came up, “there’s a bunch of people in ICU that want to hug you.” His pants stiff from the drying salt water, his shoes soaked with diesel fuel, his body exhausted, he got on the elevator. Not for hugs—he told no one who he was—just because he could no longer go without seeing the connection between himself and his work. Slowly he walked the halls, poking his head inside doors.

Word spread. The chief executive officer of the hospital came down and congratulated him, and shocked Dan a few days later when they passed in the hall by calling out Dan’s first name. A woman whose husband was in ICU threw her arms around him. The governor popped in to shake his hand. Nurses and orderlies noticed him when he went up for his paycheck: Hey, you’re that guy.”

At Christmas, they asked him to play Santa at the hospital party. As he left home each day, he began reaching past his Miller beer and Chevy truck hats to grab the one that said Roper Hospital Maintenance. That’s who he worked for, you know.