Ivan Passer’s film Cutter’s Way, now at the Key Theater, is one of those rare movies that has led a heroic life of its own. Like a boxer in some Hollywood ring drama, beset by skeptics and loan sharks and battered nearly to death, Cutter and Bone (the original title) was counted out—yanked from distribution after one week—but somehow got to its feet and came out on top.

United Artists had shelved the film last March, after halfheartedly trying to bill it as a murder mystery. The studio saw it as a leftover item commissioned by a pair of executives who had left the company during its filming.

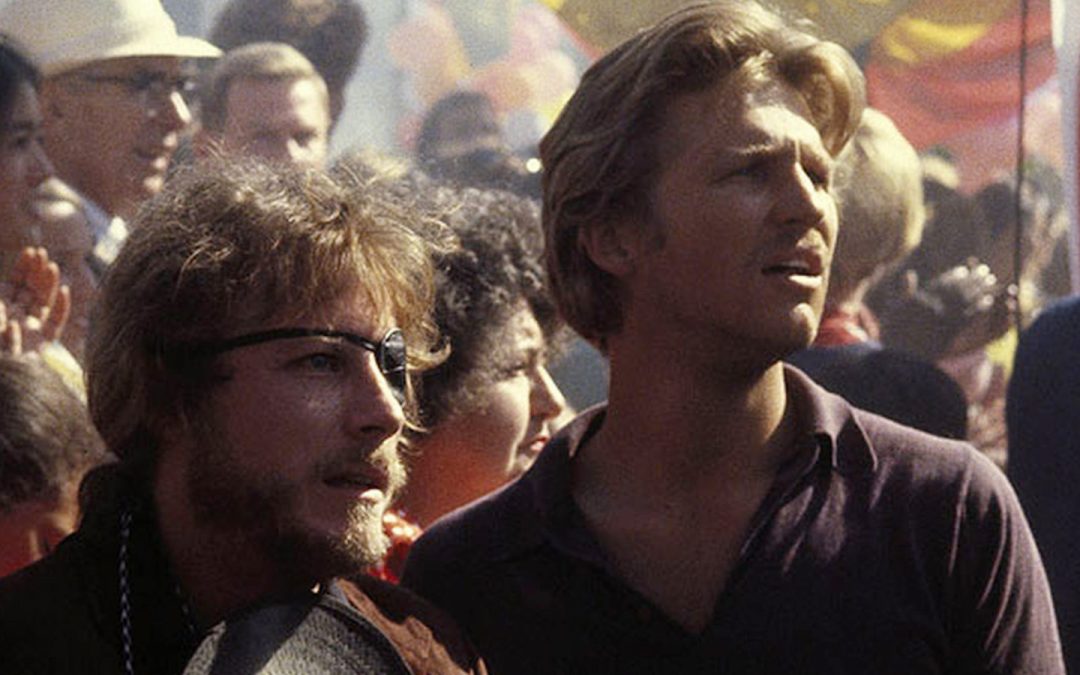

The movie was a conscientious adaptation of Newton Thornburg’s novel Cutter and Bone. Set in Santa Barbara, California, it tells the story of bitter, crippled Vietnam vet Alex Cutter (John Heard), his cynical sidekick Bone (Jeff Bridges) and the woman (Lisa Eichhorn as Cutter’s wife) with whom they’re both in love. A rich character study that is marked by immaculate cinematography and many spoken passages of almost savage intensity, the film was seen by incoming UA execs as prickly and unsaleable. They dumped it on New York last March with minimal promotion, Vincent Canby scourged it, and—as Jeff Bridges remembers thinking when the film was shelved—“another one bites the dust.”

But wait. An executive named Nathaniel Kwit Jr., then head of UA Classics, thought the film deserved the special attention of his young-and-hungry corporate division. He gave the picture a new name and marketing profile, then placed it in art houses in such cities as Boston, Seattle and New York. Good word-of-mouth pumped 18 weeks out of the film in Seattle; it’s been running equally long in New York and Boston and is going so strong that UA plans to open it in several suburban theaters outside those cities.

Those 18 weeks have been good for a gross of about $200,000 per city; combined with other rentals and a likely sale to network, cable and pay TV, Cutter’s Way seems certain to pay off its estimated $5 million price tag. It’s the sort of comeback that sets an example for the resurrection of other “art” films knocked aside by Hollywood’s inept marketing.

Ivan Passer sits in his comfortably littered apartment off Hollywood’s Sunset Strip. His manner is one of almost feline imperturbability. The 48-year-old Czech e’migre is in the middle of a crowd scene—two cats tussling among potted plants, his companion Francesca Emerson (a film editor) and this interviewer enjoying a rare reunion with a boyhood friend, screenwriter Tom Pope. Pope and Passer had just finished a work session on the script for their hoped-for collaboration, The Eagle of Broadway. Even after an hour of plotting strategies for running a maze of agents, money deals and movie stars (James Cagney and William Hurt were possibilities), Passer was calm and smiling.

Q: When you made films with Milos Forman in Czechoslovakia [Passer was co-writer and assistant director for Loves of a Blonde and The Firemen’s Ball] you had severe restrictions. But I would guess Hollywood deal-making is almost as pernicious.

A: It’s really like walking in a mine field. You can get blown off any moment. Especially because the mortality of film corporation executives is so tremendous—every three years they’re either gone, or they change chairs. The people who had put their necks out for Cutter were gone when it was released in New York at three theaters with a total advertising budget of $63,000. That’s a form of censorship—of assassination.

Q: You’ve pointed out that UA gave a party for Thief’s premiere that same week, and the party alone cost $75,000.

A: Cutter was not your average commercial sure thing. One reason I wanted to do this story was that I was getting sick to my stomach of what I called the cripple mania— Jon Voight in Coming Home, and various TV shows, the good guys got wounded and they were even better after that. I felt there was an absolute distortion of what actually goes on when somebody gets maimed internally or physically. It doesn’t usually make them better people. Most of the time, from what I have seen, it makes them dangerous.

Q: How did you go about casting the picture?

A: Casting the picture is the most frightening part of the movie-making because if you go wrong there, forget it. We were discussing many different actors and one day in New York I went to see Shakespeare in the Park—Othello. Suddenly this guy came onstage—John Heard playing Cassius—and something about his presence made the whole audience quiet down. You can feel the spark. I knew instantly that John was the actor for the part of Cutter.

Q: Wasn’t there a bit of a mishap on the way to casting Bridges?

A: It may be because of a dog this movie got made. UA was hesitating, but at one point they said, okay, the script is fine, everything is fine—if you get Jeff Bridges to play Bone you have a green light. So somebody arranged a meeting with Bridges, myself and Paul Gurian, the producer of the film. We drove out to Malibu, where Jeff lives in this nice run-down sort of ranch. We rang the bell, and Jeff came out barefooted in jeans and opens this wooden gate which looks like it’s going to fall down any minute. There were two dogs standing behind him—one sort of normal-looking German shepherd and one mean-looking cross between a shepherd and a coyote. He had his ears pointed backward and he was looking sideways at us and, I knew, not liking us at all.

We said hello. Obviously at that moment you don’t say too much—you can blow the project right there. So Paul leans forward to kiss this dog. And suddenly it jumps. It looked like it bit off his left cheek. Suddenly there’s this guy standing there with a frightened expression, bleeding profusely. Jeff said, “Oh my God” and ran for his car and we put Paul in. Luckily there was a plastic surgeon who was building his house nearby. They worked on him for about two hours. We never discussed the film, but obviously [smiling] Jeff had no choice.

Q: There’s been some talk of an Academy Award for Heard. How thoroughly did he immerse himself in that part?

A: He was walking around with a cane for three weeks before the picture, and he stayed into it throughout shooting. But also, somehow the character was very close to something real in John. Not that John is Cutter but some of John is Cutter. It’s a gift to be somebody else and be yourself at the same time. I think that’s something one cannot learn.

Q: Jeff Bridges described your directorial style to me as “a gentle presence.” And despite all the emotional warfare the characters go through, he felt there was “a great evenness” to the finished product. I think a good part of that comes from your camera placement—it’s relatively conservative.

A: The critics say, and I sort of accept it, that I am a fan of the “invisible” camera—not trying to show what you can do. That was the advantage of being four years in film school. You get rid of it there. Godard said once that the movement of the camera is an ethical problem. I think that’s true in the sense that you can be responsible or irresponsible in the way you move the camera with regard to the subject you are trying to tell about. You can be arrogant—or honest.

Q: That scene in the morgue in the last reel—where you watch Cutter’s face and not what he’s looking at—is remarkably taut.

A: Immediately after is the cut where he comes out, and the way he takes it, when he says, “Tragedy I take straight. It’s the daily grind that gets me.” And I hope you like him for that. That suddenly you see the guy … I do daydream sometimes about getting a script in my hands and raping it, which means use all the tricks I know as a director regardless of what it has to say. But I think that’s the discipline a director should have. Not to use your tricks any more effectively than the story needs. It always amazes me when I see John Ford’s work, or William Wyler’s work, or that of Kurosawa—or Ozu, the amazing Japanese director who moves me the most because he’s so economical in the way he moves you. They used only what was necessary.

Q: It’s almost like you have a second life as a director. Before you and Forman fled your home country, you stood for the Czech New Wave. The States is an entirely different climate.

A: We had an opportunity to investigate unknown territories in filmmaking there, because we used non-professional actors. Milos liked to mix them with real actors, as he did here in Cuckoo’s Nest—you can’t tell the difference. We were among the first to leave the studio, go out in the street with the camera. Or go to real apartments, put real people in front of the camera. Before that you had films where steelworkers would live in $200,000 apartments and speak this very cultivated language.

Q: Was the Czech government coming down on you?

A: They finally did. After The Firemen’s Ball they got really angry and refused to distribute the film. In the fall of 1967, a few months before Dubcek came into power, they accused us of being anti-people or whatever and we were an item for discussion on the agenda of a party congress.

Q: Czech politics at the time seem quite confounding.

A: The country was in political turmoil. Things were happening so fast that people read different things into that film every month, according to circumstances. It was fascinating. You know, film is not really dead celluloid. It changes all the time.

I like a few films to the point where I go to see them every three years or so, and they always look different. I have already experienced this with Cutter’s Way. I went to see it in New York … I was just going to check the sound and the print, but suddenly I got involved in the story and I was moved by Lisa, moved by the “Mo” character more than ever before. So I realized that already there’s a distance between me and the film, that I can watch it as if I had nothing to do with it. You know, it’s funny, because I always feel a little embarrassed about being a filmmaker. You ask people to give you two hours of their lives.

Q: That’s okay. You’re in a leisure society now. Wasn’t your departure from Czechoslovakia a bit scary?

A: Well, yes. It was six months after the Soviet invasion, and we knew that it was just a matter of time before the borders would be closed. Milos and I didn’t want to get stuck there, because we knew it would mean the end of our filmmaking careers. We didn’t have an exit visa, so we chose a small border point on the Czech/Austrian border, got there at 4 o’clock in the morning. There was one guard there, no traffic. So we showed him our passports and he said, “Where is your exit visa?” While we pretended to be looking for it, thinking, “What are we going to do now?” he said, “Aren’t you Milos Forman, the film director?” and they began to discuss The Firemen’s Ball. Then he said, “Where are you going?” and we said we were going to Vienna for the weekend. He said, “Forget the exit visa,” and opened the gate. When he said goodbye to us, he used a word which means, “Goodbye, be with God forever.” That was the 10th of January, 1969.

Q: I understand your son recently cleared the border and is on his way here. Is he a potential filmmaker?

A: I told him to find some respectable profession. Many people will look at a guy and say, “Well, if you’re so bright and educated, why aren’t you in business?” I actually had a job in France before I came here. Milos talked me into coming here, but I didn’t come expecting to make movies. Before I went to school I was a bricklayer, a steelworker, and I worked with a jackhammer. I worked as a laborer, building a dam and things like that, so any job would have been fine.

I used to think, this country has so many good filmmakers, why would they need a Czech to make American movies? It didn’t make sense. But, as often in life, when you don’t really want something very much, it somehow comes to you.