A mile or so from the spot where Jackson Pollock came to a messy end on a lonely stretch of Long Island black-top, Jann Wenner is sliding his silver Dino 308 GT4 Ferrari through a long, graceful turn. Route 114, between Sag Harbor and East Hampton, is a smooth, winding, lollipop of a road made for fast driving, and Wenner, as he pops the car into fifth gear, is doing about one-tenth the speed of sound. The summer before, he totaled an almost identical Ferrari on the tiny racecourse near Bridgehampton and walked away from it.

But on this hot morning in midsummer, the living is easy and the driver’s mind is on the Ferrari at hand. An advance tape of Bob Dylan’s newest album, Empire Burlesque, is turned up loud on the Blaupunkt, and the sun is beginning to burn off the morning fog. The night before, Wenner had enjoyed a quiet dinner at home at his expansive beach house with his wife, Jane, his 15-year-old niece, Megan, and her girlfriend, and Richard Gere and Gere’s girlfriend, Sylvia Martins. Then the founder, editor and publisher of the most influential music magazine ever, a onetime feverish rock groupie who used to paper his office walls with backstage concert passes, went into the living room with his family and guests, curled up on the sofa with a cocktail, and, like 40 million other Americans, watched Live Aid on television.

Jann Wenner is running a pair of dimpled hands through a stack of postcards and photographs on his credenza. He is looking for a picture of the Ferrari in question. In between taking phone calls from the publicist for the movie Perfect or from one of his many lawyers, he continues his rummaging. There are snapshots from Clay Felker’s and Gail Sheehy’s wedding, a postcard from Rio (“I love getting postcards”*), a picture of Wenner and former Rolling Stone managing editor John Walsh at the office party last Christmas. But no car shot. The telephone rings in an outer office and a moment later, Wenner’s secretary, Mary MacDonald, comes in. “Country Joe McDonald?” she says. “I’ll call him back.”

At his desk, in his car, walking, standing, lying down, Jann Wenner is a firm, round, five-foot-seven-inch, thirteen-stone, barrel-shaped bundle of raw nerve, energy and contradictions. His face, even after decades of high living, is ruddy and clear and full of color. He has azure, vault-of-heaven eyes that twinkle in the presence of friends, and a boyish, free- for-all smile that can freeze the most determined foe. His hands are like those of a pipe fitter’s, thick and weathered. He has gnawed the sides of his thumbs to a rough, white coarseness. His fingernails he has chewed down to flaky, round chips. He has small feet (size 9½ D) that seem barely to balance his body. He has broad shoulders and a thick neck, and even in his most expensive clothes he can look like a longshoreman in his Sunday best. Out for a stroll up Fifth Avenue, he walks head up, elbows out, with the athletic, jaunty swagger of a pigeon-toed boulevardier-—Lou Costello in a Giorgio Armani suit. When there is an urgency, his body tilts forward twenty degrees and his short legs move like stubby pistons. Back up in his Rolling Stone lair, Wenner is incapable of going the full length of a corridor in a straight line; he is constantly bobbing in and out of offices, beginning conversations while he’s still in the hallway and then moving on while the second half of the colloquy is in mid-sentence.

One morning he is smoking long, thin, queen-sized Nat Sherman Cigarettellos; the next day the pack is gathering dust on his desk. He’ll wolf down three gin and tonics at The Sherry Netherland one evening and get by on club soda the next. When he dips into his office refrigerator for an afternoon pop, it is even odds whether he’ll emerge with a Diet Sunkist or chilled Wyborowa vodka, both of which he will drink straight from their containers. He is on a diet of greens and popcorn one day, and the next is ordering three crab cocktails and a bowl of potato chips with an after-work drink, joking to the waiter that “I’m in a definite mood for gaining weight today.” He occasionally eats noisily while on the telephone, has been known to lunge across a dinner table to sample a guest’s order. When he gets especially excited, bits of food can spray from his lips.

He walks heads up, elbows out, with an athletic, jaunty swagger—Lou Costello in a Giorgio Armani suit.

No matter how fast he talks, his mouth can’t keep up with his thoughts, and often his words tumble out in an incoherent mumble. The editor of a magazine that has won two National Magazine Awards and has been heralded as the voice of its generation, Wenner once insisted at a party that Virginia Woolf was a member of the “Doonesbury Set.” He can, over a single lunch, pronounce Waugh as “woe,” query a dining companion as to the meaning of “capricious” and refer to Kentucky Fried Movie as Kentucky Fried Chicken. Once, when an editor asked him why he wanted Joe Eszterhas to head up a book-review section in the magazine, Wenner shot back: “Because Joe reads!”

He is a plump, pink capitalist who became a public figure at 23 and was named one of Time’s 200 “Faces of the Future” when he was 28. And with his energy fueled by a $1 million-a-year paycheck, he has driven himself, his wife, his friends and his employees not a little crazy by his wild, diverse passions for ideas, for things, for people, for life. To those who have worked under him, he is the most brilliant and the stupidest, the most generous and the most petty, the bravest and the most cowardly editor they have ever known.His many friends would walk on fire for him. His enemies would prefer he walked it alone. To those who know him, he is better looking than he is in his photographs and a better person than he is in his press. And after all the Rolling Stone profiles of all the people that have made the past three decades tick, it would appear that the magazine just may have missed one of the most complex and fascinating figures of this generation—Wenner himself.

On the eve of his fortieth birthday, Jann Simon Wenner is having a remarkable year in a life full of remarkable years. For once it seems there are enough new things going on around him to sate even his great, boisterous, catherine wheel of an appetite. Rolling Stone, the magazine that he has been running for almost has been running for almost half his life, is handsomer and healthier than ever. Circulation went over a million this summer, and the magazine has made more money in the last two years than in all the previous fifteen years com-bined. A near-frantic desire to be in the movies was fulfilled last June when Perfect opened with Wenner in the third largest role. Forget the movie’s reviews, he got good notices for his acting debut, and the film, which was about Rolling Stone, was something of a promotional windfall. This year too, Wenner purchased, then redesigned, US magazine, his first chance at tooling up a glossy photo publication since Look was yanked out from under him six years ago. Since January, he has bought three cars; a refined, three-story Georgian manor house in the Hamptons, trimmed with rose bushes and Trellisis: and begun preparations for a near-quarter-million-dollar renovation of his apartment on Manhattan’s East Sixties. And if all this wasn’t enough, Jann Wenner became a father.

All over Los Angeles the sun is shining, but in David O. Selznick’s old office on the grounds of the plantation-house studio that used to open all his pictures, the forecast is cloudy. The editor of Rolling Stone magazine is doing a screen test for his role as the editor of Rolling Stone magazine, and he’s gumming it up. His eyes are popping, he’s jerking his head around, his mouth is all crooked. Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea.

Maybe not. What was to have been a high point of Wenner’s year- his debut as a “movie star,” as he calls it- began a month before his screen test. John Travolta and director Jim Bridges were hanging out with Wenner at the Rolling Stone offices, sopping up atmosphere and getting into character, as movie people are wont to do these days, and trying to come up with somebody to play the part of the editor in the movie. The name they kept coming up with was Wallace Shawn.

Wenner, who saw the part rather differently, suggested “Rick Dreyfuss and then Michael Douglas. I also suggested Michael Keaton, Jeff Bridges and Peter Riegert.” Then, says Bridges, “I don’t know whether I thought of it or John did, but someone said, ‘Why don’t we test Jann?’ “ Jane didn’t want her husband to take the part- she thought it might prove embarrassing.

The night before the screen test, Wenner was having drinks with Michael Douglas at the actor’s home in Beverly Hills. He showed Douglas the scene that was going to be used in the test, and Douglas asked if he would like to do a reading. Douglas took Travolta’s role and Wenner ran through his own. You’ll be fine,” said Douglas when they were finished. “Just be your natural, energetic self. You know, throwing things around and saying “This won’t do at all’ and ‘What’s this? and chewing and being nervous and everything.” After dinner, they motored down to the Beverly Wilshire and ran into Warren Beatty and Isabelle Adjani, and later, pollster Pat Caddell. Wenner read through his part again. “It’s fine,” said Beatty. “Don’t worry about it. I’ll tell you a trick or two.” He told Wenner to act hardly at all and to talk very slowly. And then he asked Wenner if he had to cry in the movie. Wenner said no. A little more than a year later, the reviews came out.

Wenner got great writers when they were young and true and had energy to match his own.

Wenner, who moped around the office for two days after the film’s release, taking pulls from his bottle of Wyborowa, was paid $200,000 for acting as himself, acting as a consultant to the movie, and for use of the Rolling Stone name. He spent half his paycheck on a Cartier necklace for Jane. For Perfect’s producers, Wenner’s take was money well spent. His own doubts about Perfect’s chances for success did not stop him from getting out and thumping the bushes to promote it. And all the inherent conflicts in promoting in the pages of his own magazine a movie about the magazine and costarring the editor were somehow lost on him. His feeling was that if he didn’t push the movie, why should anybody else?

Travolta, who became enamored of his role as a star reporter in Perfect, began playing reporter in real life, questioning Wenner for Interview magazine and “writing” (with Perfect writer Aaron Latham’s help) an “actor’s notebook,” epic in its banality and bad taste, for a Rolling Stone cover story on him and Jamie Lee Curtis. The same month, Wenner put Jamie Lee on the cover of US. Perfect, which embarrassed many Rolling Stone alumni, disappeared from movie houses while Wenner’s US and Rolling Stone issues touting the movie were still languishing on newsstands. Wenner finally realized that he might have overstepped the bounds of propriety. “It was a mistake,” he says. “A bad call.”

A portrait of the artist at work: The phone rings. “Michael! Howaya. Uh huh. Uh huh. Uh huh. Ya. Uh huh. I get it.” Cupping his hand over the mouthpiece, Wenner explains that Telepictures, Rolling Stone’s partner in the US purchase, wants to give away subscriptions on a TV game show called Catch Phrase, and they need a promo line for the magazine. “Okay, let’s see,” says Wenner. “ The all-new, all-color, movie, television and entertainment magazine. Let’s do that. Wait. The all-color, movie, television, and personalities magazine. Or celebrities. Or entertainment. Just a minute. The all-color, television, movie and X magazine. Okay. Let’s try this: the all-color… wait a minute. The all-color, television- and movie-celebrity magazine. Make that celebrity and entertainment magazine. I would stick with the all-color. Okay. US, the all-color-… wait, here it is: The all-new, all-color, movie, television and entertainment magazine.”

The purchase of “the all-new, all-color, movie, television and entertainment magazine” gives Wenner his first real chance to show the world that the magic hands that created Rolling Stone can pull off a repeat performance. In some respects, his easy, early success proved a mixed blessing; he thought it inconceivable that the touch he had brought to Rolling Stone could not be applied to every other venture his eyes fell on. No sooner was the magazine paying some of its bills than its editor was sitting in the center of the floor looking around the room for something else to do.“Jann is kind of like the story of why the sea is salty,” says Charles Perry, a writer and editor who was at the magazine during its earliest years. “Somebody just dropped a salt mill into the sea and it kept on grinding out salt. He buzzes with projects, and many of them are completely awful, just terrible ideas. But some of them are very good. The trouble is, he wants to accomplish all of them. In those days, the sound of Jann coming up with new ideas was kind of like white noise.

Wenner put up $100,000 to launch Earth Times—a sort of ecological Rolling Stone and gave away a 10 percent interest in Rolling Stone stock for ownership of New York Scenes. Both folded within a year. A British edition of Rolling Stone, with Mick Jagger as the other partner, died six months after it started. College Papers, a slick Rolling Stone insert aimed at the student market, had a promising start in 1979 with Wenner’s sister Kate as editor—but in time, the magic of that waned too.

As a boom in hiking and backpacking became noticeable, Wenner started up Outside magazine, an elegantly designed and illustrated monthly filled with Rolling Stone-like writing and sons of the rich and famous—like William Randolph Hearst III as managing editor and Jack Ford as assistant to the publisher—sprinkled over the masthead. When Outside lost $3 million in its first year, Wenner sold the magazine to Mariah, the competition, reducing his loss to $400,000. In new hands, it went on to become profitable and has won a National Magazine Award.

In 1979, Daniel Filipacchi, the French publisher of Paris-Match, Lui and numerous other European magazines, bought the Look name and blew $8 million on the first eight issues of the revamped large-format photo magazine. When he called for help, Wenner came in with a token investment of $500,000, the titles of editor and publisher, and a promise to put the magazine out for a $50,000 monthly fee. He cut the staff to the bone and switched the frequency from fortnightly to monthly. Before Filipacchi pulled the plug, Wen-ner produced two issues of Look that were as slick and as good as anything he had ever done. He was hooked. Today, US is the Look that got away, his second crack at creating a European-style photo magazine for American readers. “It’s never been done in this country,” he says. “I tried to do it with Look, and that’s what I am going to do with this Despite the fervor, the purchase of US bore few of the “I see it, I want it” hallmarks of Wenner’s other explosive, fleeting passions. After making halfhearted inquiries into buying Vanity Fair, Interview, and Metropolitan Home, Wenner embarked on something unheard of a rational search plan. “We decided to look for magazines that were well under their potential,” says Rolling Stone general manager Kent Brownridge, “but had some correctable thing wrong with them.

The first sweep of candidates turned up 130 titles, later winnowed down to 15, and finally 3: Venture, The Sporting News and US. Wenner didn’t want Venture, and The Sporting News wasn’t for sale. US, which had been launched in 1977 by The New York Times Company and later sold for $1 to Warner Communications and McFadden Publishing, was for sale, but at the wrong price. “They wanted three times as much as we offered,” says Brownridge, “so we walked away from it.” About a year later, McFadden called back and Wenner rounded up Telepictures Publications, which puts out Muppet and Barbie magazines, and closed the deal. The new owners estimate that the purchase price and the money needed to reposition US as a legitimate competitor to People, and make it profitable, might eventually total $28 million.

Once the papers were signed, Wenner moved speedily, firing all but one member of the old US staff (a writer who had done some work for Rolling Stone) and supplanting them with Rolling Stone hand Christopher Connelly and some new hirings. He brought in art director Robert Priest from Newsweek and began farming out assignments to Rolling Stone regulars like Lynn Hirschberg, Merle Ginsberg and Fred Schruers. Wenner upgraded the printing stock and turned US into a colorful and promising, if often shallow, competitor in the celebrity-magazine field. “It’s not as lowbrow as you might think,” he says. The redesign has certainly created a worrisome extra competitor to Entertainment Tonight, which is working up its own print equivalent of the television show. They have seen the enemy, and the enemy is US.

Rarely do a magazine’s offices resemble even remotely the magazine itself. Rolling Stone’s, spread over two floors at 745 Fifth Avenue, do. The corridors, cool and tranquil in shades of pastel, are broken by long, glass-block partitions. There are Warhols on the walls and MTV on the televisions. FAO Schwarz is on the ground floor. The Plaza and Bergdorf Goodman are across the street. And a few blocks up Fifth stand The Sherry and The Pierre. This is candyland for Wenner a giant toy store and four great stone symbols of New York money and arrival.

Here, Wenner has been incredibly lucky. He spent $1 million moving the magazine east from San Francisco in 1977 when everybody else was leaving. Wenner, who was ridiculed back then for paying $12.62 a square foot, has a lock on the space at a marginally higher rate until 1992. Diane von Furstenberg is trying to sublet her offices on the floor above. Wenner says she’s asking $50 a square foot.

His own office, which takes up the entire northwest corner, is stately and comfortable, with a great view of the eastern drive up through Central Park. There are two tufted, brown-leather chesterfields, bookshelves filled with albums and videotapes, and a vast expanse of oak desk brought from San Francisco. Against one wall, frozen in Lucite, stands Pete Townshend’s cherry-red Gibson that he destroyed during a Rolling Stone photo session with Annie Leibovitz There is a stuffed piranha—a gift from former managing editor Terry McDonell—and a photo of the late Ralph Gleason, a veteran music journalist who was the magazine’s elder statesman. There are photos of Wenner and Lennon, Wenner and Boz Scaggs. Pictures of Jane. The baseball bat from Perfect and a fake Oscar given him by the Rolling Stone staff.

On an annotated tour of his gallery of past lives, Wenner stops at a photograph of his mother, Sim, as a young girl, dressed up for a long-forgotten Fifth Avenue parade. His grandfather came here from Russia at the beginning of the century; one man in the huge wave of Jewish immigration that flowed into the city of New York. His maternal grandfather came from England and became a judge in the city. He fought as a general in the Spanish-American War and founded the American Jewish War Veterans. “My mother,” he says, “because of her father’s position, used to lead parades up Fifth Avenue.”

Just blocks from the antique shop his grandmother used to own at Fifty-seventh and Sixth, Wenner was born. Six months later, the family moved to Marin County, north of San Francisco, where his father, Edward, an engineer, and his mother became rich manufacturing a very quintessentially Fifties product: instant baby formula. The family had a pool – Wenner’s first brush, he says, with status. From the eighth grade on he attended Chadwick, an exclusive boarding school in Palos Verdes Peninsula, outside Los Angeles.

Turned down by Harvard, Wenner began his freshman year at the University of California at Berkeley the fall John F. Kennedy was killed. He wrote a column under the pen name Mr. Jones for the university paper, The Daily Californian, and worked for NBC News in San Francisco for two summers. One year he did the traffic reports for KNBR radio. At the Republican Convention in the summer of 1964 he served as assistant to the unit manager, fetching coffee and Salem cigarettes for Chet Huntley and David Brinkley. He left Berkeley in his junior year and never returned.

After a nine-month turn on the biweekly tabloid that Ramparts started during the San Francisco newspaper writers strike, Wenner scraped together a $7,500 grubstake from family and friends, and in 1967, with Ralph Gleason peering over his shoulder, put out the first issue of Rolling Stone. (The name came not from the Bob Dylan song but one by Muddy Waters.) Forty thousand went out and well more than half came back sold. It was the height of the Haight-Ashbury and the hippie movement in San Francisco, and the market was already crowded with magazines like Eye and Cheetah, also hoping to cash in on the music revolution.

Two years later, when Rolling Stone first began to turn a profit, Wenner hired a personal publicist, then thought better of it and fired him. More than money, Wenner wanted recognition. “It came in all these little ways,” he recalls. “Like you know, within the first two weeks in business, we got a letter from Charlie Watts of the Rolling Stones, and that was a nice kind of recognition, and all we got as we got bigger was more recognition. But there were also too many humbling experiences.” When the magazine was first picked up by a national distributor, 200,000 copies began going out every fortnight to newsstands. Within a couple of months, however, the distributor delivered the grim news that more than 60 percent of these were coming back unsold. Then, just weeks after Wenner took out full-page subscription ads in ten of the country’s largest newspapers, the post office went on strike. “We had really gone off half-cocked,” says Wenner, “sending out all those newsstand copies, taking out the ads, moving into new office space and being arrogant and everything, and then whammo, we came this close to going bankrupt.”

If there was a moment when he realized that he had finally arrived, it happened in 1968. “I came to New York then.” he says, “and before that, I had been writing letters to Dylan saying, ‘Why don’t you call me, and ‘Let’s get together sometime,’ and this, that and the other thing. Then one day I got back to my hotel, and there was this message that had been left for me. It said: ‘Mr. Dylan called.’” Rolling Stone’s clout with the music industry increased exponentially with every issue. Within weeks after the magazine ran a story touting the talents of an all but unknown albino guitarist named Johnny Winter, the musician signed a $300,000 recording contract with Columbia Records.

But what eventually made Rolling Stone special was its writing. Wenner got great writers when they were young and true and had energy to match his own. Then he gave them time and freedom and space. He made many of them famous. So great were their numbers, so prodigious their talents, that there became almost a Rolling Stone school of writing. Early on he recognized the skills of Greil Marcus, Michael Lydon, Jonathan Colt, Jon Landau, Charles Peri and Ben Fong-Torres, and photographers Annie Leibovitz and Baron Wolman, and put their work alongside that of Outsidewriters like Richard Brautigan, Anthony Burgess Yevgeny Yevtushenko and William Burroughs. Many of them had moved on by 1973, but by then, the next wave of Rolling Stone writers, led by Hunter S. Thompson, was going to work. Wenner brought in Joe Eszterhas, Timothy Crouse, Joe Klein, Tim Ferris, Howard Kohn, David Weir, David Felton, Tom Powers, Tim Cahill and Michael Rogers. He brought the brilliant British travel writer Jan Morris to Rolling Stone, and he sent Tom Walfe to cover the final flight of the Mercury Space Program for a story that came to be called “The Brotherhood of the Right Stuff.”

“In those days,” says Klein, “you felt like you were writing sagas—you weren’t just writing magazine pieces.” Rolling Stone was almost always good, and there were times when it achieved greatness. It won its first National Magazine Award for its lengthy investigative pieces on the Manson killings and the murder at the Rolling Stones’ free concert at Altamont in 1971. The magazine won its second National Magazine Award for a special issue, “The Family 1976”—forty-six straight pages of photographs by Richard Avedon, without captions, of seventy-three men and women in power in America at the time. When the famed 1968 issue on rock groupies was picked up by the establishment press, Wenner took out a full-page ad in The New York Times billing Rolling Stone as “the energy center of the new culture and youth revolution.” Though the ad, which had a subscription form at the bottom, brought in only three new subscribers, the boast had elements of truth to it. For the memorable moments in the generation’s history -like the week John Lennon died- readers went to Rolling Stone the way readers in an earlier time had turned to Life. The Lennon issue went into a record printing of 1.45 million copies.

The move to New York was precipitated in part by Wenner’s own ambivalence toward San Francisco. The only time the staff felt any level of acceptance by their peers was on trips to New York. Despite a National Magazine Award and Rolling Stone’s and his own increasing stature, Wenner’s hometown made a bigger to-do when film director Francis Coppola bought City Magazine. In a story about the New York move, the San Francisco Chronicle mistakenly identified a photograph of somebody who worked at Interview magazine as Wenner. Says a former staff member: “Jann just felt that his destiny lay in New York.”

Wenner also wanted to head off the only real threat to his control of the magazine: Joe Armstrong. A handsome, cagey Texan who had become Rolling Stone’s advertising director, the New York-based Armstrong had as much of a knack for self-promotion as he did for shaking blue-chip advertisers out of the trees. Quite simply, the magazine wasn’t big enough for the both of them.

“The movie business is not a hobby, and that’s what Jann’s approach to it was—a secondary business as opposed to a primary business.”

The move proved to be physical and spiritual. Success had bred predictability, and the spurts of brilliance were fewer in New York. Writers like Eszterhas, Cahill, Perry and Fong-Torres stayed behind, and as a cost-cutting move, other staff members were let go. Wenner scooted around town with Jackie and Lee and Truman and became such a fixture at Elaine’s that he made a cameo appearance in Ron Rosenbaum’s 1979 mystery-parody, Murder at Elaine’s. He began doling out assignments to such New York writers as Nora Ephron, Gloria Emerson, J. Anthony Lukas and Carl Bernstein, who still holds the record for the top fee for a single Rolling Stone story: almost $30,000 for a dreary 10,000-word piece about journalists who were allegedly colluding with the CIA. (Even Wenner must have been slightly embarrassed by this largess; he told the editor who worked on the piece he paid $19,000 for it.) Tom Wolfe, says Wenner, got about $100,000 for this year’s thirty-one-part serialization of his first novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities.The magazine that had made its name on lengthy investigations into drug enforcement by Eszterhas now ran a Q and A of Diana Vreeland by Lally Weymouth. Word spread back to San Francisco of increased factionalism and malcontent at the magazine. “In New York, it seemed more like a job,” says Perry. “At Rolling Stone in San Francisco, we were always having staff uprisings, but usually because we thought Jann was doing something to endanger the magazine. The first one they had in New York was to demand that medical coverage -which we didn’t even have in San Francisco include shrink fees.”

Two years later, Wenner was bored with his new life in New York and with Rolling Stone when Hollywood called. Paramount beckoned with a $150,000 three-picture development deal, and when that was done, offered him another one on the same terms. Like most of Wenner’s other dalliances, this one was christened almost immediately with the printing of new stationery and business cards (JANN S. WENNER MOTION PICTURES). Wenner’s fascination with the film business was equaled only by Hollywood’s fascination with him. Says a former Paramount executive, now at Disney: “I think the hope was that the same skill and instinct he had demonstrated at the magazine would apply to the movie business and be very effective.” The deal called for some editorial hook to Rolling Stone stories, but only one of the scripts that Wenner developed had a Rolling Stone feel (a Butch and Sundance sort of movie about drug-running in the Florida Everglades that was written first by Hunter Thompson, then revised by two other writers). None got made.

Wenner warmed instantly to the secular trappings of movie making: doing deals, taking meetings, boarding the red-eve to the Coast—everything but the machinery of actually getting movies made. “It took more energy and time than Jann wanted to devote to it,” says a former Paramount executive, echoing sentiments of other witnesses to Wenner’s fleeting passion. “The movie business is not a hobby, and that’s what Jann’s approach to it was—a secondary business as opposed to a primary business.”

There were problems, too, with the myriad supporting players above and below him. “I think it was difficult for him to be in a supplicant position,” says ICM chairman Jeff Berg, who negotiated the Paramount deal for Wenner. “Having to ask people for things, for money to put up development funds, to get a go-ahead on a movie. Picture-making by definition is a collaborative endeavor, and at Rolling Stone, Jann has final cut. In the movie business he doesn’t.”

Jann Wenner’s Bottega Veneta billfold is a small, soft, brown-leather affair. In it he carries two Long Island police association membership cards, a hundred-dollar bill, credit cards, one personalized check, a picture of Jane, a picture of his dogs, Persie and Sasha, a picture of the Ferrari, his Rolling Stone ID, a pass to the East Hampton Cinemas and a picture taken during a ski holiday in the mountains seven years ago. He is shirtless in the photograph, tanned, slim and fit. “Every time I go on a diet,” he says, “I get this picture out and put it up on the refrigerator, or I’ll carry it around. I weighed 145 pounds in high school.”

For all that has been said about Wenner’s tendency to turn parlor lap dog around the rich and the celebrated, there is the corollary that they too are drawn to him. At all waking moments he has a high-spirited magnetism, an anything-can-happen aura that can be positively intoxicating. More than just funny, he is fun. In a social setting of his own design, he can be as accommodatingly gracious as a head waiter at Lutèce, fretting over the amount of ice in a guest’s drink one moment and pedaling off to welcome a new arrival the next. And though the myriad passions that can command between a decade and a nanosecond of his attention occasionally provide grist for outside ridicule, to his observers, they are an opiate in themselves. A cycling buff one year; the next, an avid skier. The National Alliance Against Violence (a nonprofit gun-control organization he established after John Lennon’s death. The Cranston campaign. Dylan. Jagger. Lennon. Scaggs. Politics. Movies. Fashion.

Wenner’s friends say that celebrities intimidate him little. That is not to say he won’t jump through hoops to win their favor and approval. “When he sees something new, or something he likes or someone famous,’ says Joe Klein, he is willing to make a fool of himself to really be interesting.” He actually warms to the challenge, says another friend, but only when it’s someone he wants to impress. I’ve seen him cow to a bartender, though.” When Wenner is out of his element, like when he isn’t in his office or in his house, he can become uncomfortable. Take him off his turf and he can get bashful, he’ll begin to mumble, actually shrink. He goes whoooooooosh, like a deflated balloon. “Jann is like everybody else,” says this friend, “only in italics.”

There is no shortage of those attracted to Wenner’s charms, and over the years he has gathered and dropped as many close friends as most other men his age. Ned Topham, a sometime film producer (Kentucky Fried Movie) and Rolling Stone stockholder who was at Berkeley with Wenner, is still close. So are early Rolling Stone friends like Jonathan Cott, songwriter Jim Webb, and former Rolling Stones Records executive Earl McGrath. During the summers he sees a lot of former New York deputy mayor Ken Lipper. His two closest friends, though, are Michael Douglas, whom he met when the actor was doing The Streets of San Francisco, and Richard Gere, whom he met in New York. “What do I ask of a friend?” says Wenner. “Loyalty. Fun. Love. All to be totally returned but in lesser amounts. Because I’ve got so many things to do. “

When Wenner courts a potential friend, contributor or celebrity, he pulls out all stops in the grand seduction. He once wanted a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist to write for the magazine and charmed him mercilessly. The writer obliged, turning out a number of first-rate pieces, but within months, Wenner had tired of him and wouldn’t even return his phone calls. The Rolling Stone corridors are littered with the ghosts of writers he wooed and complimented, then overworked, burned out and estranged or discarded.

He is a man who can walk out of a negotiation, having skinned his opponent, and go to a movie that night and cry all the way through it. “I’m sentimental about everything, “ Wenner says. “I can be very cynical in my judgments about things and the way they work, but if I think that there is somebody in trouble on our staff, I’ll do whatever I can.” Each year he spends $25,000 of his own money for a Rolling Stone office party. Soon after Derek Ungless began his job as Rolling Stone’s art director three years ago, he fell ill and required hospitalization. One of the first people to come to the hospital was Wenner, who had flown in from the Hamptons just to see him. When a young staffer’s child was born with birth defects, Wenner quietly sent him a gift of many thousands of dollars.

“I’ve seen him chew people out for cheating by $10 on their expense accounts, and I’ve seen him give staff members $1,000 when they get married,” says Brownridge. “I have an 85-year-old father and a 75-year-old mother who live in Los Angeles. When Jann was out there shooting Perfect, he called me up and asked if I thought my parents would like to see a movie set. I said I thought they’d love it. So he called them up and had them to lunch at the studio commissary, and then took them over to the set and arranged for special seats and introduced them to John Travolta. He spent the whole afternoon with them.”

Wenner’s obsession about loyalty to the magazine and to himself both attracted Rolling Stone’s enormous wealth of talent and drove so much of it away.

Wenner, like everyone else, wants to be loved. But as easily as his boyish sense of fun endears his friends, he has a brash, almost naive candor that doesn’t sit well with a lot of people. He is often quoted saying ridiculous things that get a lot of people, most of whom don’t know him, fired up. Those who are diffident in their feelings—a not-endangered species—include people who have eaten at the next table at restaurants, former employees, Rolling Stone profile subjects and people he brought in to run the magazine in its early years. “He was so young,” says Brownridge, “that a lot of people thought they would go in and save him from himself. And a lot of older people said, I’m going to show you how to run the company, kid.’ Jann bumped heads with a lot of these people and may have been obnoxious when he was younger.”

But the same driven, blind-to-the-wishes-of-others bulldozering may have been the very quality needed to give life to Rolling Stone in the first place. “He had a vision of what he wanted it to be, and he was able to inspire other people with it,”‘ says Charles Perry. “‘He is able to get people to believe that where he is, is the best place to work. And what made Rolling Stone work in the first place was that there was somebody who was devoting every ounce of energy he had to the magazine.”

Wenner’s obsession about loyalty to the magazine and to himself both attracted Rolling Stone’s enormous wealth of talent and drove so much of it away. Disloyalty, or his perception of it, has always been the greatest sin, and pity the assumed culprit, who soon becomes the subject of pettiness, abuse, and finally expulsion from the magic kingdom. There were “‘reigns of terror” recalls a former editor, when the sheer sound of Wenner’s footfall in the hallway would drive those in the office into a near tizzy of fear and apprehension. Many of the writers who gave the magazine its reputation drifted away—to movies, books, other magazines, idleness. Many, Wenner just drove out.

But he leaves most names on the mast-head, and each year a number of the Rolling Stone family members return home. In the last year and a half, Thompson, Crouse, Cahill and Klein have all written for the magazine. Wenner says he would have all the writers and major business people back save two. (Far more than two say they would never go back.)”Jann’s problem isn’t that he fires too quickly,” says Brownridge. “It’s that he hires too quickly.”

Former Rolling Stone writer Chet Flippo wrote a thesis on the early days of Rolling Stone and mentioned in passing similarities between Wenner and Harold Ross, the founder of The New Yorker. Whereas Ross mentioned his friends within the pages of the magazine, Wenner puts his friends on the cover. (Douglas has been a cover subject once; Gere three times.) For years, Rolling Stone and The New Yorker were the only magazines that regularly ran 10,000- and 20,000-word stories. “He was the best boss I ever had because he let me do what I wanted,” says Klein. “One year, I spent four or five months working on a single story about a guy in Ohio who was dying of cancer after working with polyvinyl chloride. Jann didn’t say ‘What are you working on?’ or “Why aren’t there any pieces coming through?; he just let me do it.” But those times are past. Straight Arrow’s whimsical Boy Scout logo no longer appears in the magazine. Wenner says he is “more interested in the magazine’s new fashion spreads than in reading a 20,000-word Eszterhas opus on almost anything.” In a series of double-page ads in a trade publication, the magazine’s new ad campaign focuses on “perception” and “теality.” Perception, in one of the ads, is a Volkswagen camper. Reality is a Mustang. Perception in another is a dog-eared 1970 Rolling Stone with Jimi Hendrix on the cover. Reality is a glossy 1985 copy featuring David Letterman. A cover line announces that an interview with Eric Clapton is somewhere inside. The magazine that once prided itself on flying by the seat of its pants and instinctive trend-spotting now sometimes defers to cover testing and focus groups to determine the likes and dislikes of its audience.(Wenner says he uses the groups to test “the few marginal cover subjects the magazine runs each year.”) The magazine whose editors once product-tested head-shop paraphernalia now runs stories on what VCRs to buy. In the past year, only David Black’s two-part series on AIDS and Earry Rehfeld’s story about rock drummer Jim Gordon’s murdering his mother had the earmarks of old Rolling Stone stories. “It’s the times,” says Wenner. “In the old days we did investigaive pieces because nobody else was doing them. Now 60 Minutes does this sort of thing, and I really don’t think we have to devote 20,000 words to something television has just done. Magazines hit a moment. Esquire hit its in the Sixties and we hit ours in the Seventies.” Still, the perception of many staff members from the magazine’s heyday is that the reality is wanting.

Like Ross, Wenner is at times intellectually dwarfed by his staff. Some felt that his invitation to former presidential speechwriter Richard Goodwin to open a Washington bureau had more to do with the editor’s wanting to hobnob with the Kenedys (Ethel actually allowed the Rolling Stone staff to use Hickory Hill while they searched for more permanent headquarters) than with any deep-rooted interest in politics. I remember that summer” Says Joe Klein “Jann flew in for Goodwin’s foreign policy dinner and he’d invited people like Les Aspin and Anthony Lakeland they’re all talking about shoe imports and Jann is sittin; cross-legged on top of Goodwin’s stereo, flipping through a magazine. And the next morning, he asked me,’How do you like it here?’ And I said, ‘Look, I don’t think that I’m going to fit in. This just doesn’t work for me.’ And Jann said, ‘Yeah, it doesn’t work for me either.’ ”

There are 8 million Jann Wenner stories in The Naked City, and it may have been that the editor’s very tics and faults bonded the staff most. The man known as “Yawn” in Doonesbury still looms large in conversations between members of the extended Rolling Stone family. “It’s like an industry,” says a former editor. Anecdotes about Wenner move through the grapevine with alarming speed, picking up almost mythical qualities as they are passed along. The soup story is now part of Rolling Stone lore. The truth is that Wenner was having lunch with Jackie and a couple of other book editors when he developed a roaring double nosebleed. But the story has grown in its telling. “As I heard it,” says Perry, “he was with everybody he wanted to impress—Truman, Andy, Princess Lee, Caroline and Jackie. And they went to The Four Seasons and Jann was gesticulating and being ingratiating, and suddenly he developed this double nosebleed, and supposedly it landed in Jackie’s bowl of consommé.I would have preferred it to be a cream soup-for the graphics.

“Jann has always had a fetish for the mast-head,” says Perry. “One year I kept track, and in twenty-six issues, there were only two where he didn’t diddle with the masthead in some way. Hiring. Firing. Changing job descriptions. And at the end of the year, I went out to a trophy company and had them make up a huge, garish, multitiered trophy. At the very top there was a hand holding a bridge hand, and around the base there were winged roller skates heading out in four different di-rections. And there was a little plaque at the bottom that read: JANN S. WENNER. MASTHEAD EDITOR.” Two years ago he hired onetime managing editor John Walsh—for a fee of $8,000—to headhunt for a new managing editor. After Walsh looked around and proposed a list of names that eventually included his own, Wenner called Marianne Partridge a former senior editor, and asked her, “Why did I fire Walsh?’*

Wenner’s relationships with his family members are no less complex. “Our family is too egotistical to live in the same city. Even the same state,” he says. His mother is in Hawaii and his father lives in Los Angeles and looks after his real-estate investments. One sister Merlin, 35, unmarried and the mother of an 8-year-old, lives in Marin County and sells real estate. Wenner is closest to his sister Kate, 37, a segment producer for ABC’s 20/20.

If there has been a constant in Wenner’s perpetual whirlwind of change and false starts, it has been his wife, Jane, a lean, tangy sprite with wise, wily eyes. They met at Ramparts, and Wenner fell hard and fast, telling her the first week that he was going to marry her. The couple’s marriage, which has seen treacherously rocky times and a number of separations, is now in its eighteenth year. During breakups, friends say Wenner shuffled around and was miserable. At the office, he became even more irrational than usual. But when they are together, says a former editor, they draw something from each other that is intangible but no less real. “I’ve seen it,” he says. “They get it out of each other. There’s an incredibly complex mutual bond there. I’ve seen it many, many times, and it manifests itself in intensity.”

“Jane has always been a stabilizing force in my life,” says Wenner. “She’s very, very smart and she’s very perceptive about people. She loves me. And to get married to someone at 21 and to have survived all these years, and managed to keep up and to cope with me, which is a problem to begin with, is amazing. She has been able to move from just sort of marrying this kid and then having to entertain Jacqueline Onassis or the president of a bank or Alan Cranston or the deputy mayor or eighteen movie stars or all the glitterati of the world. And she does it great, although she doesn’t really like it. She’s not what I’d call a corporate wife, but when you have to count on somebody, she’s there. And she’s hysterically funny. She’s my best friend. Absolutely.”

In meetings, Wenner is Stravinsky and the minions the orchestra. In a one-minute period he can be gracious and brusque, crude and brilliant.

When he’s in the office and not on the phone to Jane or Michael or Richard, Wenner has meetings, many of them, anything from random drop-ins to discuss layouts to proper executive functions with agendas and performance reports and sweaty-palmed underlings. “Jann loves meetings,” says a friend. Here Wenner is Stravinsky, and the minions the orchestra. With little or no prep-aration, he can grill Rolling Stone executives in their areas of expertise, pointing out flaws in their planning and growing impatient when tasks that were to have been done, haven’t been. When things wander, he snaps them back in an instant. In a one-minute period he can be gracious and brusque, complimentary and eviscerating, crude and brilliant. When meetings run on beyond his attention span—not long—he becomes fidgety, like a kid on a long car ride, his body stretching out farther and farther in his chair until he is finally reclining on it like it’s a divan. At other times he will curl himself up in a ball, and a moment later appear to be expanding his way across the table at the person on the other side.

Rolling Stone has always been what they used to call a “weekend hippie,” and even in its earliest days, Wenner bristled at its being called a rock tabloid or an underground paper. Luce, not Leary, was his hero. Rolling Stone was first and foremost a business concern. Music coverage was its product: politics, show business and everything else were peripherals, and when profits or audiences waned, Wenner always went back to the original merchandise.

A year and a half ago, Wenner sacked managing editor David Rosenthal, who didn’t like music, and brought back former Rolling Stone assistant managing editor Bob Wallace, who did. Circulation is up one third over a year ago, and is twice what it was in Rolling Stone’s mid-Seventies heyday. And despite a cover-price increase from $1.50 to $1.75, Wenner announced in July a rate base of 1 million circulation. This growth has not come without a price, however. The quest for greater and greater circulation figures has meant softening the magazine, a loss of consistent literary and journalistic edge that has alienated not only many former writers but many former readers. Revenues have climbed to $38 million this year from $28 million in 1983, and this year’s profit is $5 million. There are two quick yardsticks for determining a magazine’s sale price: one year’s revenues or its earnings multiplied by ten. By these two measures Rolling Stone is worth between $38 million and $50 million, and the Wenners own 80 percent of it.

Fingering his gold Rolex, his Siberian husky Addie at his feet, the purchase papers on he Mercedes 300 TD station wagon freshly signed, Jann Wenner is at his desk, feet up, attempting to explain to his niece Megan what a yuppie is, and words are failing him. “You know what a yuppie means?”‘ he asks. “It stands for young, upwardly mobile. ..or young urban people or professional or some-thing. It’s all these people, you know, with BMWs and Rolexes who play … squash!”

“I’m your yuppie success story, ne plus ultra,” says Wenner as he strolls about the grounds of the beach house that he and Jane rented through October. (This is their seventh and last year renting in the area. Next year, they move into their new summer home, a lofty Georgian manor close by, accessible by a tree-lined, quarter-mile of driveway) This day. Wenner is dressed in rubber thongs, khaki shorts and a monogrammed dress shirt, with the shirttails hanging out. “Jane told me to change into this shirt,” he says. “She said that what I had on made me look like a box.” The house lies sheltered in a sprawling, manicured compound of a half-dozen other gray, weathered beach houses on the eastern tip of Long Island. Ralph Lauren had it last year. The house the Wenners rented in the past has been turned over to Calvin Klein. Playwright Herb Gardner leases one of the houses on the estate, too.

The Wenner place is expansive and graceful, with gray-shaked exterior walls and sieep, pitched roofs. Wenner moves in to play daddy, picking his son up and cooing and gurgling at him. If there was an element missing in Wenner’s life in the past, it was children. He is godfather to Joe Eszterhas’s daughter and Jim Webb’s son. “Having a family was the only thing I felt that was missing and wanted. I love children,” he says. The adopted answer to this dream is responding to his father’s antics with big, alert eyes, and his father is loving it. It is time for Alexander’s afternoon nap, and up Wenner goes with the nanny to the nursery, a near Victorian pleasure of thick white linen, muslin, lace and wood. Wenner kisses his son, then puts him to sleep.

Fatherhood, maturity, and the times have had their effect on Jann Wenner. He says he has given up drugs and Elaine’s. On nice nights these days he leaves the office at 7:30 and walks up Fifth to his brownstone in the East Sixties. If he’s in the office in the mornings, he’ll occasionally go home for lunch.In the evenings, after the baby is in bed, he and Jane have dinner together, then settle in to watch TV. Wenner makes the occasional call to the Coast, but he’s generally in bed by 11:00. Dinner parties, when they have them, are small, with close friends like Douglas and his wife, Diandra, and Gere and Sylvia Martins. They go out for dinner maybe once a week, usually to Elio’s or Parma.

“I’ve begun to realize that I’m about halfway through life,”‘ says Wenner. “I’ve become very aware of older men. Not so much about what I am going to look like when I’m their age, but I pay attention to their alert-ness. The last time I was in California I went over to Swifty Lazar’s, and mentally, he is still this fucking firecracker. Whereas my father, who is much younger, is already beginning to repeat himself.”

At CBS’s West Fifty-seventh Street studios, Wenner has just finished a Morning News interview with Maria Shriver. Saying Goodbye to Amy Rosenblum, the segment’s Producer, and to Morning News book critic Digby Diehl, Wenner heads out of the green room. Down the corridor lopes a tall, gangly fellow with a great shock of shoulder length salt-and-pepper hair. Arlo Guthrie. There is a moment of awkwardness as these two central figures from a time long past bring each other up to date on their doings. Wenner talks about US and Perfect. Guthrie says that he has just purchased a small radio network based in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, but that it doesn’t broadcast yet. “That’s what’s happened to the revolution,” says Wenner, lighting up a Cigarettello and heading for his limo. “Arlo Guthrie buying a radio network that doesn’t broadcast.”

Taking his Ferrari back over Route 114 to Sag Harbor, Wenner notices two envelopes with pictures of his son fluttering on the dash. As he reaches over to put them into his lap, fatherhood, the automobile, the feel of the road, take him back. “My father loved sports cars too,” he recalls. “And he used to have this old MGTD with these little battery-powered windshield wipers. And we used to go skiing to Squaw Valley all the time when I was a kid. And quite often, during a heavy snowstorm, the batteries would run down and I’d have to hang outside the window with my father holding on to me and work the wipers by hand. God, I loved those days.”

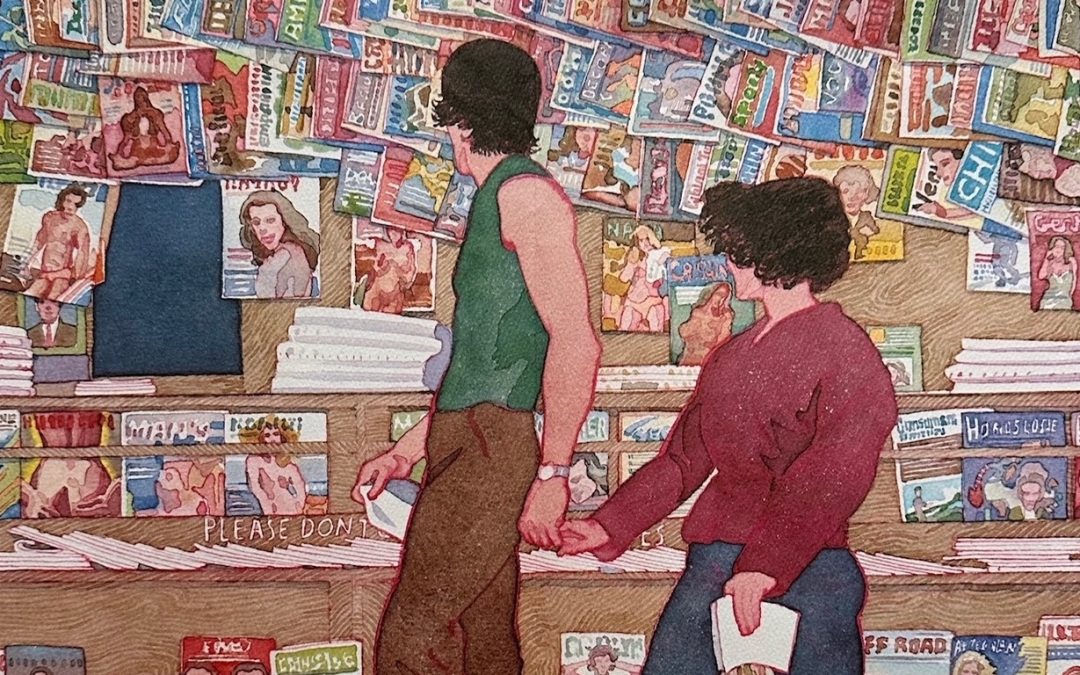

[Featured Illustration: James McMullan]