The guide cupped his eyes against the sunlight and watched the man pick his way up the cliff. Where to? he wondered. Why?

Their raft had ridden out the rapids and reached a place where the river rested. There the group of vacationing men had stretched out to feel the sun, to float upon their backs in the water. One of them had grown restless. He’d swum to the bank and begun to climb the cliffs that flank the Colorado.

“Come down!” the guide shouted. “It’s dangerous up there! Just move along the ledge a little farther and inch your way down.”

Carefully the man looked down the steep drop of shale and reconsidered the river’s depth. “Screw it,” said Joe Biden. “I’m jumping.”

On campaigns, on rivers, on mountains, this was Joe Biden’s way. Often he was spectacularly right. Sometimes he was painfully wrong. He had jumped into a Senate race at age 29 against impossible odds—and become one of the youngest senators in U.S. history. He had hurled himself down a ski ramp when he was just learning the sport—and separated his shoulder.

Now, six months before the primaries, few in America had yet to distinguish him from the pack of announced Democratic candidates for President. He found himself not in a race, but in the two-year plod through press conferences and banquet speeches, photo opportunities and coffee chats that the American presidential quest has become.

Let the other candidates inch their way down the slippery slopes of a presidential race—Joe Biden was jumping.

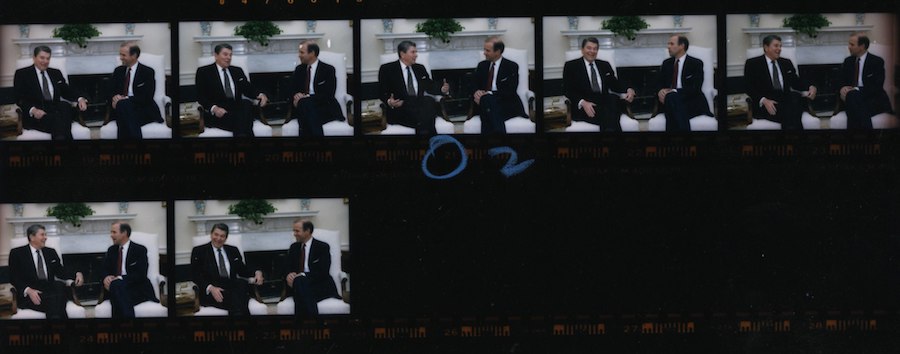

Then one day a moderate judge in the Supreme Court resigned, and a week later Ronald Reagan nominated a conservative heavyweight named Robert Bork to replace him. Suddenly it appeared the court would swing sharply to the right for years and years. Suddenly the 44-year-old Delaware senator had what he craved—the cliff ledge.

In the Senate’s confirmation hearings, before hundreds of cameras and notepads and a national TV audience of millions, he could arc through the air and make a clean, perpendicular dive into the presidential waters—or belly flop onto the rocks. In the most hotly contested battle over a Supreme Court seat in American history, Biden—the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee—had decided to lead the charge against Bork.

“Biden versus Bork … make or break,” he said. “It’s an exaggeration, but the presidential test and the Bork test have become one and the same in the minds of many, many people.

“Short term, it may hurt me. People in Iowa like to see you and touch you, and I’m losing a lot of time in the field. Long term, if I get past Iowa, it could be phenomenally good in a general election. I like the challenge. I like the platform. Robert Bork doesn’t understand the soul of the Constitution. This is high-stakes stuff for America. This is the most important thing I’ve ever done.”

Let the other candidates inch their way down the slippery slopes of a presidential race—Joe Biden was jumping.

One morning on a recent campaign stop in Iowa, after he had shaken all the strangers’ hands and made all the small talk seem not completely awkward, after he had sandpapered a soapbox go-cart for the cameras and hit two jump shots from the corner and tried on some boxing gloves in the ring and done all the other things that certified he was worthy of being America’s next President, they asked Joe Biden to absolutely prove it. They asked him to karate-chop a block of wood.

The wood was hard white pine, one inch thick. A man who did not commit all of himself to the motion could shatter all the bones in his hand.

Photographers aimed their cameras. Spectators craned their necks. Two of his aides looked at each other and asked if they should step in and stop it. Biden had never karate-chopped a block of wood in his life.

“Some people call me rash,” he says. “I’ve never been rash. For me that’s not a chance. I knew I could do it.”

He edged close to the karate instructor and whispered a request for instructions. He likes to take risks, but always on his terms.

He was roaming the country telling voters that something was wrong in America, that alarming numbers of her children were using drugs or contemplating suicide, that “their values are being perverted by our culture … for too long we have sacrificed moral values to the mere accumulation of material things … for a decade, led by Ronald Reagan, self-aggrandizement has been the full-throated cry of our society … In this gathering of discontent … my candidacy gains its voice!”

Would people with microwave ovens and remote-control televisions and videocassette recorders respond to that message? Perhaps Biden was risking, but only after massive hours of briefings and pollsters’ studies led him to believe that America was sated by Reagan’s banquet and ready to run off its fat. That a huge generation of baby boomers were finally having children and ready to think of issues beyond themselves.

“People in America have become too comfortable,” says Delaware Democratic committee chairman Sam Shipley. “It has been like talking to a wall. It will take someone with color, imagination and passion to break through that wall.”

And there stood Biden, his handshaking hand raised up near his opposite ear, his eyes staring at a spot on the wood. His body spun; out lashed his forearm. The block of wood broke cleanly in two. “That boy,” said Biden’s brother Jimmy, “wants it baaaaaad.”

“Honest to God, I believe I’m going to be the next President,” he’d say more than once, leaning very close to touch your wrist with his fingers, to drill through your skepticism with his blue eyes and perfect smile. People who meet Biden often leave feeling as though they’ve been cultivated, enlisted, sucked into the current of his personality. But a poll in early June showed that 80 percent of the voters had never heard of him, so he spent the summer cramming for the Bork battle and racing for airplanes, bent on drawing 240 million people close enough to feel the force of his will.

“Don’t tell him he can’t be President,” warns Marty Londergan, a friend since boyhood. “All that does is throw gasoline on his fire. He’s an infinitely restless man—he couldn’t be a senator for life, that’s not enough challenge for him. He can’t sit still. He runs like a long-distance runner while his aides drop around him. He leaves them in the gutter and picks up new ones. He’ll literally go until he can’t go anymore, then limp home with walking pneumonia.”

“I think Americans worry about a man who lusts for the presidency,” says Republican political consultant Roger Stone. “Voters look for a certain serenity, the kind Reagan has. Joe Biden is hot to be President.”

In a small room a few months ago in Nashua, N.H., with powerful klieg lights cooking the audience, Biden was at home. He took off his suit jacket, unhooked the microphone and paced the stage, crying out against the unchecked individualism and smugness in the land, exhorting the baby boomers to shake off their cynicism, to care, to follow him. The applause grew. His passion spread.

“Some people think there’s a certain way you have to be to become President,” says Biden. “Everyone is so worried about making a mistake, they become so plastic, and that’s one of the reasons people aren’t voting.”

“Just because our political heroes were murdered does not mean that the dream does not still live buried in our broken hearts,” he says over and over in his speeches, his voice brimming with emotion. “…I ask God’s blessing, that He raise America up on eagles’ wings, and bear it on the breath of dawn, and make the sun to shine on it!”

Deep passion? Or oil on the surface? When he talked in the South, didn’t a drawl creep into his voice? “Part conviction,” says Bill Quillen, ex- superior court judge in Delaware, “part passion … and part theater.”

Sometimes when Biden spoke, people stood and cheered wildly. Sometimes they wept. And sometimes they squirmed in embarrassment or discomfort. Simply to stay in control when he stood before the public did not intrigue him. He had to calculate how close he could go to the edge without misstepping.

Twice last year, during a verbal firefight with Biden in a Senate hearing on Reagan’s policy of “constructive engagement” toward South Africa, George Shultz literally squirmed, grabbing the arms of his chair, lifting his weight and moving his buttocks. But the Secretary of State never changed the look on his face or the tone of his voice. Biden? He struck the table, shook a copy of the administration’s policy statement in the air, clenched his teeth and screamed. “I’m ashamed of the lack of moral backbone. I’m ashamed that this country puts out a policy like this that says nothing. Nothing!”

“I don’t want a man running the country that flies off the handle like that,” says a businesswoman in Biden’s home state.

“That wasn’t Biden losing his temper,” says Roger Stone. “That was Biden posturing for the cameras.”

“The only white man I’ve ever seen who speaks with conviction about the black man,” said a black woman who shook his hand in Iowa.

“I didn’t lose my temper,” says Biden. “I’m in total control. I was angry, but I knew precisely what I was saying.”

“The goose-bumps candidate,” says Biden fund-raiser Bob Osgood. “But I know that makes some people in my Wall Street world uneasy.”

With Bork, Biden planned to show a different side. “The best thing I can do is lay out my position in as dispassionate a way as is possible,” he said, “and then let people decide, I don’t want America to go this [Bork’s] way. If I beat Bork by being shrill and browbeating him and making him crack, everyone deeply concerned about the depth of the issues involved will say, ‘Great,’ but the majority of Americans won’t like it.”

Still, the question persists: Do we prefer to be emotionally challenged by our leader or, as by Reagan, emotionally comforted? “Excuse me,” said a woman when Biden leaned very close to her at a New Hampshire gathering. “You’re invading my space!”

On your left, a half dozen Golden Dragon Head Chompers. On your right, Joe Biden, then a 20-year-old lifeguard at an inner-city pool in Wilmington, Del. They have barber’s razor blades; he holds six feet of chain. Just that morning Biden had caught Corn Pop strutting and bouncing on the high-dive board, breaking the rules. “Hey, Esther Williams, get down!” Biden had hollered, and kicked him out of the playground.

Everyone cringed. A previous lifeguard was said to have received an 85-stitch slice down the back from a gang, and sure enough, as Biden later walked to his car, there was Corn Pop waiting with his boys to settle up.

“I never liked the feeling of being out of control,” he says. “I don’t even like to take aspirin.”

In a gush, Biden began to talk. “I was right to kick you out of the pool, and I’ll do it again if you break the rules, but I was wrong to call you Esther Williams, and I won’t do that again. Let me tell you something, Corn Pop—you might cut me up, but I’m going to wrap this chain around your head if you do. Just you, Corn Pop, I’m going after you.”

Corn Pop called off the carving. Biden dropped the chain he had no idea how to use, and by the end of the summer the Head Chompers were his buddies. This was classic Biden: talk your way into a mess, talk your way out. “I turned lemons into lemonade,” he says, grinning widely.

“We had a team in a touch football league after college,” says Marty Londergan. “He’d taunt the other team, throw the ball at their chests to rattle them, to instigate them. And then when the fight started, he’d be on the sidelines holding everyone’s coats. He was a smart aleck, a wise guy. He’d rub a lot of people the wrong way. A lot of it was to cover up a feeling of inadequacy.”

As a boy Joe looked up to his father, a tall, stately man who exuded control, a sales manager for a car dealership who wore an ascot to entertain, matched shirts even to his shorts and rectified an elbow on the dinner table with a withering glare. “Champ,” he called his firstborn, but often Joe didn’t feel like one. He burned to be masterly, too, but he was the second smallest in his class, he had asthma and he stuttered. “B-b-b-b-biden,” the children snickered when he read aloud in class.

With the encouragement of a proud, close-knit family, he attacked his problems. He filled two coffee cans with cement, attached them to a bar and pumped them to grow larger, ate bananas even though he didn’t like them and milk shakes by the score. He recited Emerson aloud in front of a mirror and studied the movement of his lips. Knowing the teacher in his Catholic school would call on each student in alphabetical order to read a paragraph, he calculated which paragraph would be his, memorized it and yoked it with a cadence. It would set a pattern for his life: working feverishly in private to come off as a natural in public. By his senior year in high school, he was his team’s leading scorer in football, the commencement speaker at his graduation.

One drink—save for diplomatic toasts—that’s all in 44 years he ever remembers taking. Always it was Joe who did the driving. He never liked to dance, to yield his reason to his torso. “I never liked the feeling of being out of control,” he says. “I don’t even like to take aspirin.” Years later he would exasperate his aides with his inability to let go, demanding to know even the design of the invitations for the annual staff picnic.

He was handsome, well built and could charm the glower off a Head Chomper, but the more he found he could control, the closer to the edge he had to inch to feel the gratification in controlling. Wearing just a jockstrap, he shocked classmates his last year in high school by darting across campus on a dare and touching the statue of Saint Norbert. He went months barely studying at the University of Delaware and at Syracuse University law school, then borrowed buddies’ notes the night before the tests and outscored them.

But he didn’t forget how it felt to hurt inside, to have a problem. He befriended a stutterer in law school and worked with him on his speech every night for a half hour. He stopped in the rain to help people change tires; he jumped from his car to chase muggers assaulting a woman.

A man in that much command of himself and the molecules around him could make plans. “The first day I ever met him,” says Jack Owens, a Syracuse classmate and now Biden’s brother-in-law, “he said to me, ‘I’m going to marry my girlfriend Neilia, go back to Delaware, become a criminal lawyer and then become U.S. senator from Delaware.’ ”

He married Neilia Hunter, a woman with beauty-queen looks and dean’s-list smarts: She delivered him three children and became the check on his impulses, the ballast in his life. He became a criminal lawyer, leaning into juries’ boxes to make them feel the heat of his sincerity. He won a Democratic seat on the County Council at 27 in a heavily Republican district where he was given little chance, and then, when he was given noneagainst a popular incumbent, a U.S. Senate seat.

He took the Capitol steps two at a time, life in his hip pocket. On December 18, 1972, two weeks before he would take the oath, he sat in his new office interviewing applicants for his staff as Neilia, 100 miles away in Delaware, drove home with the three children and the Christmas tree. Pulling out from a stop sign, she never saw the tractor trailer.

Neilia and 13-month-old Amy were killed, their two sons injured. “I thought I could control everything,” says Biden, “that I could guarantee my destiny. Why could I not have controlled this? Why couldn’t I have been there?”

He punched a hole through a wall in his house, and walked the streets for hours at night, bristling when someone brushed his arm, aching to hit and be hit, trying to exhaust his rage. He told the governor of Delaware to look for someone else to fill his seat, then was talked out of it by Senator Mike Mansfield. His sister moved in to help him raise his boys; his brother Jimmy accompanied him on the haunted walks at night. Shunning the capital’s social scene to be home with his children, Biden began the nearly four-hour round- trip commute from Wilmington to Washington that has been his pattern for 15 years. “I did my job and went home, period,” he says.

It wasn’t until he met a schoolteacher named Jill Jacobs in 1975 and married her two years later that the rage leaked from him. He became known as one of the Senate’s best speakers and brightest minds. The brilliant smile returned to his face, and at 39 he became the father of a little girl named Ashley, now 5. The raft had ridden out the rapids. And there was Biden climbing the cliffs again, and jumping. “If I weren’t running for President,” he says, “I’d probably spend my spare time learning to drive a race car. Seriously.”

But who is he? people asked. His need to be at home had kept him off the weekend newsmaker shows; so had his tendency to devour an issue, then catch scent of the next, rather than to keep chewing on one and become well known for it. And it didn’t help, as the Bork hearings began, that Biden was found to be using unattributed passages from the speeches of Robert Kennedy, Hubert Humphrey and British Labor leader Neil Kinnock. The candidate’s love of oratory—of words for their own sake—made people wonder what he really stood for.

Biden is liberal. He wants to shift money from the military budget to education and guarantee a poor child free health care to the age of 12—and yet he is not consistently liberal. He refused to budge from the tarmac of a South African airport in 1976 until authorities allowed him to walk through the blacks-only entrance with a group of black congressional colleagues—but he voted against busing. He supported a woman’s right to abortion but voted against federal funding of abortions.

“Some people think there’s a certain way you have to be to become President,” says Biden. “Everyone is so worried about making a mistake, they become so plastic, and that’s one of the reasons people aren’t voting. But I don’t want them to package me. Governance isn’t some antiseptic, passionless exercise.”

During SALT II discussions, when Premier Aleksei Kosygin used a number Biden knew to be low in speaking of Soviet troop strength in Eastern Europe, he put his hand on Kosygin’s arm and said, “Don’t kid a kidder.” In 1984 in Moscow he told Georgi Arbatov, head of the Soviets’ Institute of United States-Canada Studies, “All right, Georgi, cut the crap. Your economy is in a desperate situation, your philosophy is dead, no one’s buying that song and dance anymore.” He would deal with Gorbachev the same way he did with Corn Pop, say his friends: Strip away all his props with one bold verbal thrust, singularize it to just Joe leaning very close, one on one with Mikhail.

Biden’s insistence not to sacrifice his family to his restlessness has become almost ferocious. One day in late August, he stood on a porch at his son’s high school as 17-year-old Hunter ran through preseason football drills in a driving rain—the only father watching. Another day he sneaked in a 15- minute catch with 18-year-old son Beau during a staff meeting at a beach house, when aides thought he had only gone off to the bathroom. The effect the campaign could have upon his wife and children makes him uneasy. During appearances he often has Ashley in his arms or at his side, stroking her cheeks with his fingers, keeping her and Jill within the reach of his hand. A man cannot control something distant, his life had taught him, but a man of heat and force, if he could find a way to stay very, very close….

In Washington, D.C., just before Biden began the speech that declared his candidacy, Beau stood as his father kissed him. Hunter, seemingly less comfortable with such a public display of emotion, darted offstage untouched. And maybe, in the end, that’s what Joe Biden’s chance to be President would hinge on: How many Hunters are there in America? And how many Beaus?

[Photo Credit: Wiki Media Commons]