The child in the child is somehow faded. She is eight years old but there is nothing in her manner to say she isn’t nineteen, with a house full of screaming babies and a high school sweetheart who doesn’t always come home at night anymore.

She walks the front yard like walking is already a chore, collecting the mongrel puppies. There are nine of them and her fingers disappear into the long coats as she picks them up, then puts them in a cardboard box next to the front door.

The house is a shack, about a block from the abandoned half-mile dirt track where LeeRoy Yarbrough, the most famous man ever to come out of west Jacksonville, Florida, got his start racing automobiles. About three blocks from the place where, a month before, cold sober, he tried to strangle his own mother.

“He live right up that road there,” she says, pointing a puppy. “Him and Miz Yarbrough, but they ain’t there now. Everybody knows LeeRoy, sometime he come by and sit on the steps, but now he wrung Miz Yarbrough’s neck, he ain’t home no more.”

The screen door opens and a woman in white socks steps halfway out the door. Missing teeth and a face as narrow as the phone book. “You git them puppies up yet? You know what your daddy tol’ you.”

The door slams shut, but the woman stays there, behind it in the shadows. In west Jacksonville it always feels like there’s somebody watching behind the screen door.

“We got to take the puppies down to the lake,” the girl says. “Daddy got back from the country [farm] and says so. He goin’ take them out to the lake with him tonight.”

I ask her why she just didn’t give the puppies away. She shakes her head. “I tol’ you,” she says. “Daddy got back from the country.”

I’m going to tell you right here that I don’t know what picked LeeRoy Yarbrough off the top of his world in 1969 and delivered him, eleven years later, to the night when he would get up off a living room chair and tell his mother, “I hate to do this to you,” and then try to kill her. I can tell you some of how it happened, I can tell you what the doctors said, what his people said. But I don’t know why.

It has business with that little girl and her puppies, though. With not looking at what you don’t want to see, putting it off until you are face-to-face with something unspeakable.

And tonight those nine puppies go to the bottom of the lake.

A Short History

“They ain’t ever been no fits on neither side of the family. That’s how the doctors knowed it was them licks on the head that made LeeRoy how he is.” Minnie Yarbrough is LeeRoy’s mother. She is seventy-six years old, and she’s sitting on the couch in her living room, as far away from the yellow chair in the corner as she can get. That is where it happened.

It’s an old house on Plymouth Street, in west Jacksonville, brown shingles, a bad roof, the porch gives when you step on it. An empty trailer sits rusting in the backyard. Inside it’s dark. The windows are closed off and Minnie Yarbrough keeps the door to her room locked any time she isn’t in it.

“I was born and partial raised in Clay County, Florida. Mr. Yarbrough was partial raised in Baker County. Both of us come from Florida families, Baptists, and there was never no fits on either side. Mr. Yarbrough died in 1974, but he’d of mentioned it if it was. We was together forty-three years…”

Lonnie LeeRoy Yarbrough was one of six children. He was the first son, born September 17, 1938, and named after his father, who ran a roadside vegetable stand.

Lonnie Yarbrough hauled the vegetables in an old truck and played penny poker with his friends to pass the time.

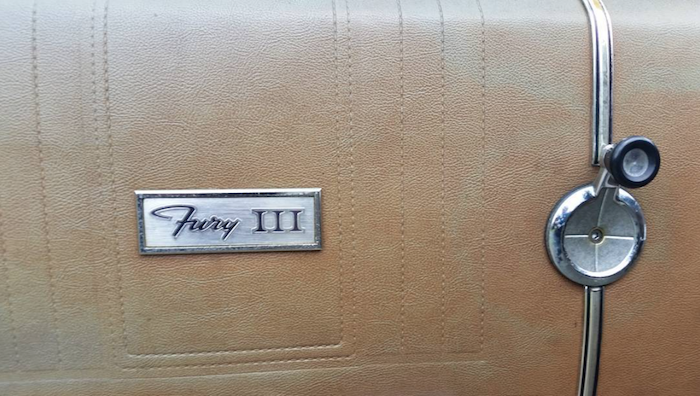

LeeRoy passed his time at Moon’s Garage. He put his first car together when he was twelve—dropping a Chrysler engine into a 1934 Ford coupe—and wore the police out stopping him along the back roads of west Jacksonville. He quit Paxon High School after the tenth grade, and he won the first race he was ever in at Jacksonville Speedway when he was sixteen.

Even now, sitting in the Duval County Jail, waiting to be processed out to a state hospital, he can tell you exactly what he was running that day. A 1940 flat-head Ford, bored out 81/1,000ths of an inch, with high-compression heads.

He can tell you that, but he can’t tell you who is president.

In 1956 LeeRoy married Gloria Sapp, who was sixteen, and became friendly with Julian Klein, who would later own the Jacksonville Speedway. “I been knowin’ LeeRoy pract’ly all his life,” Klein says. “He come right out on top in the old modified days, had it all in the bag right from the beginnin’. His impulses was sharp as a tack, but it got to his attitude. Sometimes he was cocky, sometimes he wouldn’t say nothin’. He had a temper, but not too much for a dirt-track driver.

In west Jacksonville it always feels like there’s somebody watching behind the screen door.

“I carried him to Daytona with his first car. It was obsolete, and we was too ignorant to know it, but he come in thirteenth anyway. After that we won about every race we went to. But he was gettin’ too big too fast, tryin’ to race too many races, and his wife was already out in the bars on him. Got to where he wouldn’t even be on time.

“We was comin’ back from South Carolina one Sunday, stop at this place in Jesup, Georgia, called The Pig—that’s where we’d settle up—and I looked at him and made up my mind to change drivers. I’m sixty-six, been around racin’ all my life, and in his day I haven’t seen nobody any better. But it was time. I didn’t tell him right out. Knowin’ LeeRoy, I thought I’d space it out. I didn’t get through sayin’ it till we was back in Jacksonville. He didn’t seem to mind, like it didn’t matter.

“He never come back out to the track after he got big. He went on fishin’ trips. He didn’t care, but it didn’t make you feel better seein’ him these last years, walkin’ up the street in a daze, pickin’ up soda bottles to turn in for a quart of beer down to the store.

“Nobody who was ever LeeRoy Yarbrough oughtn’ to end up like that.”

LeeRoy Yarbrough entered his first Grand National race in 1960, won his first one in 1964. It was two more years before he won on a super speedway, the Nationals 500 at Charlotte.

Three years after that, driving for Ford in Junior Johnson cars, he had the greatest year that any stock-car driver has ever had.

He won seven NASCAR Grand Nationals, all on super speedways. His winnings were almost $200,000. He kept about half of that, along with a regular salary from Ford and fees for tire and engine tests. He bought a seventeen-room house on Lake Murray near Columbia, South Carolina, an airplane, a boat, cars. When a reporter asked that year about his early days, he said he’d been a juvenile delinquent. “I don’t let myself think about some of what I did,” he said.

For half a year, every other banquet south of Indiana named him man of the year. The papers were full of pictures of LeeRoy in the winner’s circle, sometimes holding a trophy, sometimes his son LeRoi, getting kissed on the cheek by Gloria.

And by that time Gloria was called “Sweet Thing” in big racing towns all over the South.

Even though he was its top driver in 1969, Ford never used LeeRoy much for personal appearances. He stayed to himself, and Ford let him. He was quiet, but every now and then he’d hit somebody, usually without much warning. He would brag to the newspaper writers, or not talk to them at all. Or tell them he was sick. Nineteen sixty-nine was the year LeeRoy Yarbrough began to get sick.

Paul Pruss, who handled public relations for Ford racing, said, “I suppose you could say he was respected. He didn’t wrestle bears or anything.”

The year after that, in April 1970, LeeRoy crashed at College Station, Texas, during a Goodyear tire test at the Texas International Speedway. He came out of it unconscious. Later he wouldn’t remember the flight home, or Cale Yarborough (who is not related) picking him up at the airport and driving him to the next race in Martinsville, Virginia.

That whole year LeeRoy won only one major race, the Charlotte 500, and at the end of the year Ford pulled out of racing. LeeRoy and Junior Johnson split up.

In May 1971, driving a Dan Gurney car, LeeRoy went into the wall during practice for the Indianapolis 500. His hands and neck were burned, and he took another serious crack on the head. It was the sixth or seventh major accident in his career, and probably the worst.

Cale Yarborough was the first person after the doctors to see him in the infield hospital. “His color wasn’t good, like he’d seen … I don’t know what. It was a bad crash, a terrible one. He was frightened, and he should have been.”

LeeRoy spent the rest of the year in the minor leagues, winning thirty-seven late-model sportsman-class races, mostly in the Carolinas, because he couldn’t find a car to drive on the Grand National circuit.

He was in and out of hospitals from June to November, and toward the end of the year he began telling people that the doctors had traced his troubles to a case of Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

The year after that he was back on the Grand National circuit, driving a Bill Seifert Ford. His best finish was a third at Dover, Delaware, but he was fourth twice, fifth at Charlotte and Atlanta, sixth in the Firecracker 400. Respectable.

And then he was gone. Gone from racing, gone from the house on the lake in Columbia. He took his family back to Jacksonville and disappeared.

He lost his money in a business deal with his uncle, Willie Lee Yarbrough, lost his children—LeRoi and Dawn Nichole—in the divorce settlement in 1976, the court placing the children with Willie Lee and his wife, Ernestine, setting conditions that neither LeeRoy nor Gloria was allowed to visit the children “within a period of 12 hours of either party consuming alcoholic beverages.”

He went back to live with his mother in the brown-shingled house on Plymouth Street. LeeRoy and his mother and a house full of racing trophies that never got polished.

“All his life, he was a momma’s boy,” Minnie Yarbrough says. “When somethin’ got to eatin’ on him bad enough, he always come to me for what he needed.”

Sweet Thing and a Two-Dollar Part

Junior Johnson is sitting on a tractor in fresh overalls and a starched T-shirt, arms big enough to lift an engine block and there’s not a hair on his head out of place.

The tractor is sitting nose up on the bottom of the creek that runs through twenty-six acres of land that Junior owns at the foot of Engle Holler in Rhonda, North Carolina.

Besides the twenty-six acres, Junior has seventeen fulltime employees, fifteen coon hounds, thirty-nine cows, 92,000 automatically fed, climate-controlled chickens, and three or four businesses connected one way or the other to his racing cars.

All that and a tractor stuck in the creek bottom. On the bank above him, two of his employees, eleven of the cows, and a dog named Red watch him try to get out. He kills the tractor engine twice, shakes his head, and whistles.

As soon as Junior does that, one of the men scrambles to help him up the bank, the other one goes for the jeep. The cows change positions, and in the distance, a fight starts in the dog pen. Junior just waits for the jeep, and when it gets there he climbs in to be the one to pull the tractor out.

Junior Johnson runs things personally.

You get the feeling that it must half kill him when he sends somebody else out to drive the cars he puts together.

The tractor comes out on the second try. Junior leaves the cleaning up to the help and walks across the road toward his office, scraping at the mud on his boots. A man meets him at the door with his lunch.

In the office he unwraps a hamburger, folds the paper before he puts it in the wastebasket. “LeeRoy,” he says. He thinks it over, nods. If you believe Junior Johnson’s reputation, this is already a long conversation.

“I liked LeeRoy,” he says finally. “Didn’t talk much, he was a great driver—good as Cale or Donnie [Allison]—best I ever had at goin’ from one kind of car to the next. He was universal that way, like A.J. Foyt is. I like him, but I don’t make a family association with drivers.

“By LeeRoy’s time, they wasn’t a lot of hard drinkin’ and partyin’ goin’ on anymore. If you done that you got caught up with. Oh, they went to dinners and parties and such—a lot of them boys even had airplanes. I never cared too much for parties or airplanes myself. I know too much about mechanical malfunctions…”

Three days before, at Atlanta, Johnson’s Chevrolet—with Cale Yarborough driving—had problems with a bad rotary button twenty laps from the finish. That is a two-dollar part in the distributor, and the way the race was going Junior figures it cost him forty thousand dollars.

“Chickens,” he says, “now that’s a reliable thing. Controlled conditions. But racin’—any little thing can happen and throw it all out the door.

“When I heard what happened to LeeRoy, it surprised me, but maybe not so much as others. When Ford pulled outta racin’, I couldn’t afford to keep on at the same level. Me and him never had a formal split-up or nothin’, we just went our ways. But the last time I saw him, I seen trouble comin’. You could sort of tell he was changin’, his appearance weakened.

“No, I got no idea what caused it. The doctors says it was mental damage. I’ll believe that. LeeRoy, he stayed to hisself, except for his family. That’s what he had. You take somethin’ complicated, say like a race engine, push it to its stress limits, sometimes a two-dollar part is goin’ bust and take you out the race…”

They called her Sweet Thing.

She was married to LeeRoy Yarbrough twenty years, a little blond girl who drank at the races and put her hands on the men when she laughed.

“It was the booze that put the pressure on his brain,” she says. “It had to be somethin’ more than a lot of licks on the head. I can’t believe in my mind seven or eight years had to pass before any of this would of showed up. I wisht I could of helped him. I wisht I could help him even now, but I got a life of my own to live.

“Up until 1970, I never saw LeeRoy drunk but on Christmas. Along about that time he took to drinkin’ Monday to Thursday, be he was proud, you know, didn’t want nobody to know it. So he’d say he was sick. That was his way of coverin’ it up, sometimes he’d go to the hospital.

“That’s how that story about Rocky Mountain tick fever got started. He was in the hospital with alcoholic seizures—he’d grit his teeth and shake all over—and the man settin’ in the next bed says, ‘LeeRoy, maybe you got Rocky Mountain tick fever,’ so he come out and that’s what he told everybody.” (The Medical University of South Carolina refuses to release the medical records.)

“For LeeRoy’s whole life,” Gloria says, “when he done somethin’ bad, he’d always say he didn’t remember it. He thought people didn’t know if he didn’t know. He’d get drunk and bad-dispositioned, but people’d want him around anyway. He is a private person who was never allowed no privacy.

“When we lived out to the lake in Columbia, he’d go off on the boat sometimes in the mornin’ and wouldn’t come back till after dark. Just take him some half-pints out and sit in the middle of the lake all day. He always bought booze in half-pints. I ast you, what could you be doin’ sittin’ in the middle of a lake when you got a family and a beautiful home?

“Either that or it’d rain and he’d lock himself in the office upstairs. He had an office filled with them hot-rod books. He’d go up there all day and read them. Later on, back in Jacksonville, he’d buy him a quart of beer at the Majik Market and just go out in the woods and sit in a tree.

“When we left Columbia, we had $200,000 in cash. Miz Yarbrough never liked me, and she and Willie Lee always tried to get me and LeeRoy apart. What for? You figure that out. The only thing I brung out of that divorce was fifteen hundred dollars, and nine hundred of that went for the lawyer.

“After we split up, sometime he’d call up on the phone and wouldn’t say nothin’. I always knew it was him, and one time little LeRoi answered and I took the phone and said, ‘I know it’s you, LeeRoy.’ He started cryin’, said his momma was gone, and he was lonely. A grown man.

“Look, I’d like to help, but I got a new husband and a new life…”

Ask a little about the old life, and she won’t talk about her problems, says there weren’t any problems with the law. “I thought this was s’posed to be onto LeeRoy,” she says. “I think the less said about me the better.”

Dan H. Stubbs, Jr., has been the Yarbrough family attorney for thirty years, and some of the sorrows and failures of those years are collected in his files. One of those folders is for Gloria.

He shuffles through it now. “The last time I kep’ her out of jail was 1976. Charge of disorderly intoxication. On a Monday.” The police report says Gloria Yarbrough was drunk and belligerent and abusive to the staff at the hospital detoxification center. It also says Gloria is five feet, three inches tall and weighs 188 pounds.

A year and a half before that was drunk driving on a suspended license, and she only weighed 142.

He goes through more papers. “She remarried,” he says. “I guess she’s got the kids now.” He shrugs, closes the folder.

Sweet Thing is about to turn forty years old and has a new life, a new husband, and a job at the electric company. “I only wisht I could of done somethin’ to help,” she says.

Wicky-Wacky

By February of 1980, LeeRoy Yarbrough had lost contact with his wife, saw his children only at Christmas. Of his four sisters, three of them—Libby, Lillian Sweat, and Evelyn Motel—still lived in the area, and he’d see them once in a while when they came to visit Minnie. There were no old friends from the racing days—there weren’t really any of them even then. And there was his brother Eldon, a dirt-track driver who never made it beyond that.

“People ought to know better but they don’t. When LeeRoy drinks he just gets…radical. This hurts me so bad. If nobody’s around him, he’s all right, but you got to leave him his distance.”

“Eldon, he don’t think about LeeRoy.” Terry Sweat is LeeRoy’s nephew and lived in the house with him and Minnie Yarbrough. He is seventeen, and it was up to him to stop LeeRoy from killing his grandmother. He is in the house now, waiting for her to come home from the store. A radio is on too loud in the kitchen. “Eldon,” he says, “is only interested in his cars.

“Here, let me turn off that nigger music so we can hear…” He gets up and walks into the kitchen, the music stops. “My daddy done more for LeeRoy than Eldon ever did. Whenever LeeRoy was beat up, laying in a ditch, it was Daddy who went with Grandmother to get him. When the police had him and called, it was always my father who went with her down there to the station.

“All the kids around liked him. They’d holler, ‘LeeRoy, LeeRoy,’ and he’d go over if he was sober, play with them half the afternoon. The neighbors liked him too, he was famous. A lot of them, though, they’d give him liquor.

“One neighbor lady, she saw LeeRoy walkin’ back from the Majik Market with a quart of beer one day and she ast him would he like a drink. He says yes, and she says what would you like?

“She had three different kinds of liquor, and he took every one and poured it into the quart, and right there in the yard he drunk it down. He says, ‘Thank you,’ and goes on his way, gets on my motorcycle and runs it into a ditch.

“People ought to know better but they don’t. When LeeRoy drinks he just gets…radical. This hurts me so bad. If nobody’s around him, he’s all right, but you got to leave him his distance.”

By February of 1980, LeeRoy Yarbrough only had one person left. That doesn’t mean there weren’t others who cared about him. And whatever else there is to say about it, the night LeeRoy tried to kill his mother he was strangling the last person he had left in the world.

Minnie Yarbrough is a long time coming home. She says the Winn-Dixie was crowded. “Some day I maybe can live this out,” she says, “but it hurt deep. If he’d had al-kee-haul was what caused it, I could understand. But he hadn’t had nothin’.” She stops, confused. “I can’t talk on it no more right now.

“There was nobody ever really knowed LeeRoy’s background,” she says. “Maybe even me. But I know this: a woman can make a man or she can break him, and Gloria put LeeRoy to the dogs.

“Onct she called me up to South Carolina, she says I got to come and sober LeeRoy up. So I got in the car and drove up to their place on the lake and throwed all the liquor out the house. I walked right over and took them out. The house was disgraceful messy. LeeRoy was out settin’ in the boat. I said, ‘Gloria, this here is a ruin-nation.’

“And I got right back in the car and drove home. After they’d broke up I tol’ her, ‘When I was tryin’ to show you your points, nobody could tell you nothin’.’ She said that she resented me, and she jus’ wisht she could live it over, it’d be different. I tol’ her, ‘No it wouldn’t, but that’s water done run under the bridge.’”

After LeeRoy came back to Jacksonville, he went into business with Willie Lee and Ernestine.

LeeRoy put up the money. Nobody is sure now what happened to it. Some lots were bought, but they are gone. So is Willie Lee. Ernestine is dead, and LeeRoy thinks his Social Security check comes from tenants in his houses.

His mother says, “LeeRoy and me, onct he come home here we never had no argument, no hard feelin’s. If he saw that red sign board outside that says STOP, if he says it was black, I’d say it was black too. If you know somebody’s disposition was set, it don’t do no good to argue.

“We lived here together. I knowed I couldn’t comfort him like a wife could. I tol’ him, ‘I can cook for you and be kind to you and keep your shirts clean, but that’s all a mother can do.’ I tol’ him, why didn’t he go git hisself a girlfriend. He’d just laugh, ast me how come I didn’t go get me a boyfriend, me livin’ forty-three years with one man.

“I don’t know what got into him,” she says, “but I know when his mind collapsed. It was early 1977, I can’t give you no date but it was a Monday morning. He was stayin’ with Willie Lee, and his sister and me had been by the day before, he was jus’ fine as anything.

“The next day Ernestine called, said LeeRoy’d been sick all night with headache. I went over and by then his head hurt so bad he couldn’t get his socks on, so I did it. I said, ‘We is goin’ to the hospital,’ and when he didn’t make me no answer, I looked at his face, and it was all changed. It was like he was lookin’ at the devil.

“Then his body drawed to the left. I got him out to the car and blowed the horn for Ernestine to hurry—Ernestine was always slow as Christmas—and when she got in I didn’t know if I could drive. She says it was better than sittin’ in the backseat and lookin’ at LeeRoy like he was.

“So I went to blowin’ the horn and flashin’ the lights and I never got my foot out the carburetor the whole way to the firehouse. They looked at him there and give us one of them paddles to keep you from chewin’ your tongue, and I drove on to the hospital. By the time we got there, LeeRoy was drawed up into a knot—like his face was tryin’ to meet with his knees.

“Next mornin’ we come in and he didn’t know nothin’. We couldn’t even tell him he wasn’t in jail. And he was wicky-wacky from then on. The doctors said it was them licks on the head and the liquor. They said it was that if it didn’t run in the family, so it must of been, but you don’t know.

“I can’t sleep no more, worryin’ on it. I don’t know why it happened, maybe God never intended us to know such. I know they is things God didn’t intend us to see.”

LeeRoy Yarbrough has been examined twice in the last three years at the psychiatric center at University Medical Complex in Jacksonville, both times at the request of his attorney, Dan Stubbs.

The first examination was in March of 1977, after LeeRoy had been sentenced to 120 days at the county farm for two different assaults on the Jacksonville Police Department.

“A lot of times the police would see LeeRoy out walkin’ around in a daze and take him home,” Stubbs said. “The older ones, they knew how to handle LeeRoy. The younger ones, they got him stirred up. And you stir LeeRoy up, you got your hands full.”

LeeRoy got six weeks for kicking a police officer two weeks before Christmas, and another six weeks for tearing up the insides of a police car six days later.

Stubbs said, “All this time LeeRoy thought he had a lot of money in the bank, but he couldn’t remember where. He said he owned three or four houses and an airplane and kept a hundred thousand dollars in his driving helmet. And if you’d tell him to go to the store he was likely to end up in South Carolina.”

On March 25, while LeeRoy was still in the county farm (eventually he was released after serving six weeks), Judge John Cox, on the basis of the psychiatric report, ruled him incompetent to handle his own affairs. By that time there were almost no affairs left to handle.

No guardian was ever appointed. “His people were afraid of him,” Stubbs said. “His mother felt she was too old, so it just sort of never got done.”

After LeeRoy attacked his mother in February, he was examined again. While that was going on, Stubbs allowed the charges against him to be increased from aggravated battery to attempted murder. (There was also a charge for punching Officer W.T. Weaver in the nose.)

“The bond on the first ones came to a little over twenty-three hundred dollars,” Stubbs said. “That means he could get out for two hundred and thirty, and I knew damn well what he’d do.”

The doctors sent the court a two-page report saying LeeRoy was insane at the time of the attack. They put the condition down to brain damage.

They called it “organic brain syndrome, non-psychotic, secondary to cranio-cerebral trauma.” Too many times into the wall. The report also noted that in cases of brain damage, alcohol can “precipitate violence and other types of distressed behavior.”

The report said something else too. That LeeRoy probably wasn’t going to get any better. “[It is doubtful] hospitalization would accrue any substantial change,” it said, and recommended a nursing home where LeeRoy could be under constant and close supervision.

On the basis of that report, LeeRoy was judged incompetent to stand trial and eventually will be handed over to the state’s Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services.

LeeRoy

They bring LeeRoy Yarbrough down from the third floor in slippers and checkered pants. It takes a minute for it to register that it’s the same man in all those pictures holding trophies with Gloria mashing in his cheek. He could be fifty-five years old.

“I don’t like bein’ touched,” he says. “Basically, I don’t know ’xactly what’s goin’ on, but one of them police and me fell onto a little bit of an argument, I know that.”

He looks himself over, a swollen stomach, arms that have lost their tone. He flexes his hands. The outline of bone-thin legs show in the wave of his trousers.

The guards at the Duval County Jail all know LeeRoy, some of them grew up wanting to be drivers too. They find a room where he can sit down to talk and get him a paper cup of cherry Kool-Aid.

“I could still drive,” he says. “Just clear up whatever this is all about first.”

Before he shuts the door, the captain says, “He’s lookin’ much better now.” As soon as the door is shut the room gets close, you feel the walls.

LeeRoy leans back in his chair and smiles. “I can’t basically tell you what’s goin’ on,” he says. “Basically, I don’t know about that.” He looks around the room. “Don’t nothin’ worry me about here. Nobody says much to me, and I got very little to say to them. We watch television…”

Outside somebody slams a steel door, LeeRoy smiles. “Jail is noisy, ain’t it? I always like it quiet, out on the lake.” He shrugs. “Ain’t no sense braggin’ about it, but I can get out any time I want. I been here about five or six days, you know.”

It is March 15, and LeeRoy has been inside since the middle of February. He doesn’t know how old he is, how long he has been divorced, who is president. He pulls the hair up off the back of his neck and bends forward to show a patch of skin about the color of a coated tongue.

“I got myself on fire at Indy,” he says. “Gordon Cooper and Gus Grissom owned the car. [Grissom and Cooper owned a car LeeRoy drove in trials at Indianapolis five years before his accident there.] We all got along jus’ fine. I didn’t talk about what I did, and they didn’t talk about what they did. I know they made a dollar a mile goin’ to the moon, though.”

Leeroy sips at his Kool-Aid. “The first I knew I had somethin’ out the ordinary was when I was fifteen. I was the biggest hot-rodder in west Jacksonville. Won my first race in a 1940 flat-head Ford, bored out 81/1,00ths, with high compression heads…” He taps the back of his head. “That’s somethin’ that stays with you,” he says.

“After that I basically married a real stinker. I kept the children, but then me and my uncle … well, sometimes things don’t work out. But I still got my houses and my airplane.”

He looks across the table and suddenly everything in the face changes. “Is the plane in some kind of trouble? If somebody’s got my plane I don’t ’preciate that, hear? When you got somethin’ of your own it’s always different from usin’ somebody else’s. If I was up there, I’d just walk in and tell him to give me the keys to the plane, and if you didn’t I just come over the desk and git them from you.” He is coming up, more on the table than his chair, when suddenly his face changes again.

“It’s somethin’ goin’ on,” he says and sits back. “I jus’ don’t basically know what it’s about, but it’ll come back. I know me too good.” He is quiet a minute, looking into his cup. “I bet my mother’s worried. I bet she’s real upset not knowin’ where I am.”

LeeRoy pulls the hair away from his neck and shows the scar there again. He talks about the crash at Indianapolis, suddenly stops. “Basically, I had a beautiful life. I married a stinker, but I kept the children. Racin’, it don’t scare you. At Indy I got on fire, and it damn sure hurts, but it don’t scare you or you wouldn’t of got there. What it is, if we know one of us is gonna be dead when we come out this room, you try to fix things on the outside first, before you come in.”

He stops and thinks again. “I could still drive,” he says. “Just clear up whatever this is all about first.”

February 13

Terry Sweat started sweetening up about five in the afternoon. “When I’m goin’ to a party I get sweetened up all the way,” he says. “Sometimes it takes me two hours.”

When he came out of the bathroom, it was after six-thirty. His grandmother was sitting on the couch, LeeRoy was in the chair near the door. “They was just watchin’ television,” he says, “and my grandmother ast me to go down to the store to get her a pack of cigarettes.”

According to what Minnie Yarbrough told police, Terry was gone about five minutes when LeeRoy stood up, went into another room, then came back and locked the front door. He said, “Mother, I hate to do this to you,” and threw her into the yellow chair in the corner and began to strangle her.

“I heard her screamin’ my name clear out to the street when I come back,” Terry says. “I run up to the front door. It was locked, but I could see in through the little window up on the top. What I seen was LeeRoy bendin’ over the chair. All I seen of grandmother was her leg.

“She was screamin’ for me, and he was yellin’ too. He said, ‘That little sumbitch ain’t getting’ in.’ Well, a lot of people don’t understand how close me and my grandmother is. I ran around to the back door, and he’d forgot about that. I come flyin’ through there like a bullet and tried to knock him off. He was like a brick wall. He was screamin’, ‘Leave us alone, goddamnit.’

“I tried to git him off, but I couldn’t. So I did what I could. I got a jelly jar out of the kitchen and hit him over the head. That hurt me so bad to do it. It stunned him—it never knocked him down—but it was long enough that I got my grandmother out of there. I took her next door to Libby’s, and they’d already called the police.

“When the first cop got there, LeeRoy about knocked him over the fence.”

Patrolman W.T. Weaver already knew LeeRoy Yarbrough. He’d picked him up the week before and taken him home. “I found him sittin’ on a porch, lookin’ lost, so I talked to him. I got him in the car and all of a sudden he grabbed my microphone, took five minutes to wrestle it away. Anybody else, I probably would of taken him in, but he seemed so frustrated, you know? I felt sorry for him.”

Weaver was the first cop to get to the house on Plymouth Street. He was followed by a backup car and the fire rescue squad. Minnie Yarbrough and her grandson stood in the next yard and watched. LeeRoy came out of the house with a glass in his hand.

“He walked to the edge of the street, and I grabbed the glass,” Weaver says. “I got that away, and he hit me in the nose.”

It took a while, but a little at a time Weaver and the other cop and four or five firemen wrestled LeeRoy down and got handcuffs on him.

Terry says, “They took him away and my grandmother just stood there in the grass, holdin’ her neck, until he was gone up the street.”

Minnie Yarbrough can’t talk about that night yet. She still feels what happened when she walks into her house, she won’t stay there alone. “They is things God didn’t intend us to see,” she says.

And LeeRoy sits downtown in the Duval County Jail, shut off from what he has done, all that he has lost. And shut off from whatever it is you see going into a wall at 170 miles an hour, or at the moment you have to kill your mother.

Time slides by unnoticed, like a day on the lake. Somewhere under the surface, though, it’s all there waiting for him.

“It’s somethin’ goin’ on, I don’t know basically what it is,” he says. “I’m just layin’ up, rollin’ with the punches, and it’ll come back to me. I know myself too good.” He sits up suddenly, his eyes narrow.

“It ain’t my plane in trouble, is it?”

[Photo Credit: Peter Richmond]