Philip Roth died a few days ago at the age of 85. My favorite tribute comes from Zadie Smith in The New Yorker:

He was a writer all the way down. It was not diluted with other things as it is—mercifully!—for the rest of us. He was writing taken neat, and everything he did was at the service of writing. At an unusually tender age, he learned not to write to make people think well of him, nor to display to others, through fiction, the right sort of ideas, so they could think him the right sort of person. “Literature isn’t a moral beauty contest,” he once said. For Roth, literature was not a tool of any description. It was the venerated thing in itself. He loved fiction and (unlike so many half or three-quarter writers) was never ashamed of it. He loved it in its irresponsibility, in its comedy, in its vulgarity, and its divine independence. He never confused it with other things made of words, like statements of social justice or personal rectitude, journalism or political speeches, all of which are vital and necessary for lives we live outside of fiction, but none of which are fiction, which is a medium that must always allow itself, as those other forms often can’t, the possibility of expressing intimate and inconvenient truths.

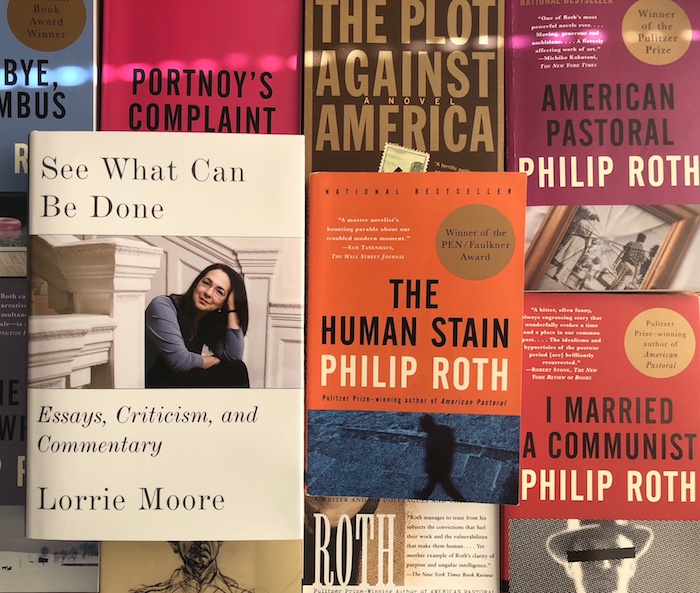

If you have never read Roth—boy is there so much to choose from. There are the classics—Goodbye, Columbus and Portnoy’s Complaint—and the later masterpieces like Sabbath’s Theater, American Pastoral, The Plot Against America and The Human Stain, which was reviewed in the Times by the novelist Lorrie Moore (the piece appears in the terrific new anthology of Moore’s non-fiction):

In terms of sheer productivity, brilliance, distinctly American diction, philosophical rage, comic irritability, dramatic representations of solitude, uniqueness of voice and unwavering repugnance toward heterosexual convention, it is difficult to think of a contemporary artist with whom Roth might even be compared. If one strains and reaches into another medium entirely, Stephen Sondheim comes to mind. Both have committed their lives to a single (if commercially ailing) art form, provocatively pushing at its margins with piercing wit and multitonal notes, for the avid consumption of the more literate members of an essentially middlebrow audience—their loyal fans.

The condition of the fan over time, however, is a complicated one. The fan’s admiration may grow proprietary, neurotic and fussy—no longer conducted in the language of love but in the unattractive tones of disappointed connoisseurship. Such a condition, with time, resembles something vaguely if unilaterally marital, replete with dashed hopes, eccentric pronouncements, insincere forgiveness, nagging, muttering and some occasional really extremely minor drinking.

Head on over to The Paris Review and dig into their 1984 Art of Fiction Interview with the Master. And then listen to his conversation with Terry Gross.