“Look, honey, yourself. Gimme a Jax.”

“Besides, how old are you?”

“Old enough to like Jax for breakfast.”

Off the lobby, which was peopled by wheezing old men propped up in cracked plastic chairs and reading the Montgomery Advertiser, an orange sign over a doorway blinked BOOM-BOOM ROOM. She took the worn carpeted stairs at the doorway and walked down one flight into the dank bar. It was done up in neo-Hawaiian, with revolving pastel lights and a phony bamboo ceiling and colored beads and a straw-mat floor, and from the Technicolor jukebox in one corner came the heavy beat of Fats Domino singing “Blueberry Hill.”

Ah foun’ mah threeal

Awn Blueberry Heeal…

Dixie wriggled onto one of the bamboo stools at the bar and checked herself out in the dappled room-wide mirror behind the bar. In the darkest corner of the room were two businessmen in short-sleeved see-through nylon dress shirts and two gap-toothed route salesmen with rows of ballpoint pens jammed in the chest pockets of their blue work shirts. Dixie pulled a Winston from her halter top and was lighting up when a plump blue-haired barmaid in a skirt slit to her thighs came up to her from behind the bar. “Honey, you cain’t wear that in here,” the barmaid said.

“Cain’t wear whut?” Dixie said.

“Well, that. Halters and short-shorts ain’t allowed.”

“You wouldn’t be jealous, would you?”

“Now, look, honey.”

“Look, honey, yourself. Gimme a Jax.”

“Besides, how old are you?”

“Old enough to like Jax for breakfast.”

“Honey, we cain’t serve minors.”

“And put it on Cantrell’s tab.”

The barmaid blinked. “Cantrell?”

“Mister Cecil Cantrell. Room Twenty-four. He’s my guardian.”

“Honey, I didn’t know—”

“Neither does he,” Dixie said. She blew smoke into the barmaid’s face. The barmaid opened an ice-cold can of Jax beer and slid it down the shellacked bar to Dixie. The four men at the table ordered another round of drinks and began ogling Dixie, talking low among themselves and motioning toward her, until finally one of them got up and approached her.

“Anything special you’d like to hear on the jukebox?” he said.

“Anything you want to dedicate to me is fine with me,” she said.

He dropped a dime into the jukebox and returned to the other three men at the table.

Kitty Kallin’s recording of “Little Things Mean a Lot” began to play. The salesman poked one of the others with his elbow and, when he caught a glance from Dixie, held up both hands about five inches apart and began laughing and nodding. Dixie couldn’t help herself. She shook her head sideways and began to giggle out of control.

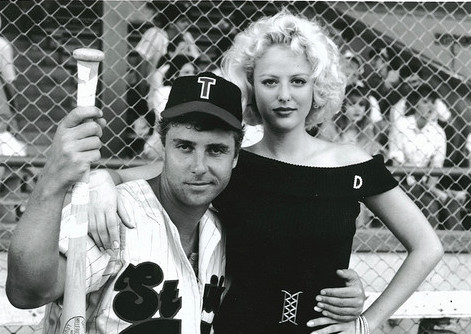

She was starting on a second beer when Stud and Jamie came in through the step-down entrance to the Boom-Boom Room from the sidewalk. Jamie still carried his bat and his glove and his spikes. Stud, squinting and making the adjustment from the brilliant sunlight to the darkness of the bar, saw Dixie and motioned for Jamie to follow him. “Well, if it ain’t Miss Crestview,” Stud said as he and Jamie hoisted themselves onto stools on either side of her.

“You got me drunk,” Dixie told him.

“That ain’t the half of it. Gimme a Jax, Bonnie. This here’s my new temporary second baseman, Jamie Weeks, from Birmingham, Alabama, and the Sho-Me Baseball Camp in Missouri. Beer, kid?” Stud slapped his cowboy hat on Dixie’s head.

Jamie said, “Just a Coke.”

“A Coke?” Stud said. “Got me a goddamn Baptist.”

“I just don’t feel like a beer right now.”

“Coke, Bonnie. Put ’em on my tab.” Stud looked at Dixie. “See you got your beauty sleep. Don’t believe we’ve officially met yet. I’m Stud Cantrell. This is Jamie Weeks. Who’re you?”

“Dixie Box—Dixie Lee Box—from Crestview, Florida.”

“Dixie”—Stud was howling—“Dixie Lee Box?”

“You heard it right. Dixie … Lee … Box.”

“You a stripper or something?”

“I roast the best cashews in Crestview.”

“Cashews,” Stud said. “Them’s nuts, ain’t they?””

“I’m not going to pay any attention to that,” said Dixie. “It would be demeaning to the people at Maxwell’s Department Store.”

“Is that”—Stud was still laughing—“is that where you work? Dixie Box? You the cashew-nut girl at Maxwell’s Department Store in Crestview, Florida?” He punched Jamie in the ribs with his elbow. “I don’t rightly recall that I ever met a real live cashew-nut roaster before. Not on a personal basis, anyway, if you know what I mean.”

“I know what you mean. Stud. Is that it? ‘Stud’?”

“Cantrell, ma’am. Stud Cantrell.”

Dixie sipped the rest of her beer. “Well, Stud Cantrell of the Graceville Oilers, you ’bout ready to go? It’s gonna take up nearly four hours, just to get there and back, and that’s if we’re lucky getting rides.”

“Go?” A pall fell over Stud. “I ain’t goin’ nowhere.”

“Sure you are. You’re going to Crestview.”

“Hell, I was in Crestview last night.”

“Sure you were. With me. We’re going again.”

“What’s this ‘we’ shit?”

Dixie said, “Me and you. Gotta get my car.”

“Wait just a goddamn minute, here.”

“Well,” Dixie said, “us crazies gotta stick together.” She wheeled off the highway and dropped Stud at Oilers Stadium.

“We gotta get my car and my clothes and my toothpaste, and I gotta leave a note for Mama, and I guess I ought to go into the refrigerator at the trailer and take out some more of the cash from Daddy’s insurance policy. Then I suppose I owe it to ’em to run by Maxwell’s and tell ’em where to put their cashews—“

“Now just a goddamn—”

“—and possibly, in case you keep on saying ‘Just a goddamn minute,’ drop in on the sheriff and tell him I’m just an innocent little girl who got taken advantage of by some mean-eyed fucker who’s old enough to be my daddy.”

When Dixie finished, she looked sweetly into Stud’s eyes and batted her lashes and said, “Shouldn’t we leave a tip for Bonnie? She’s such a nice girl. A little fat. But nice.”

Stud slammed two quarters on the bar and dismounted from the stool.

“Go ahead and check into Myrick’s Boarding House, kid,” he said to Jamie, “and I’ll take care of this. Get to the park by five o’clock for batting practice.” Jamie grabbed his bat and glove and spikes and followed Stud and Dixie up the steps, out of the Boom-Boom Room, into the sunlight on the sidewalk. He turned left, to walk toward the boardinghouse, and when he looked back, he saw Stud gesticulating wildly to Dixie as they went toward the highway to hitch a ride to Crestview.

By four o’clock in the afternoon they were tooling back eastward on U.S. 90, between Crestview and Graceville, with the top down on Dixie’s battered ’50 blood-red Chevrolet convertible. They had hitched to Crestview in one ride, riding in the back of a pickup truck with two hogs, and stopped at the ballpark to get the car. Then they had driven to the trailer park on the east side of town where Dixie was living with her mother. Dixie’s mother was off at work, in the department store downtown, so she left a note—

Mama:

I’ll be living in Graceville for a while, with a friend, so don’t try to come and get me. I got some clothes and I took $200 of Daddy’s insurance money. Don’t worry I’ll be alright.Love,

DIXIEP.S.—You’d love him.

—and hurriedly stuffed jeans and t-shirts and sneakers and toiletries into a brown paper grocery bag, tossing the bag into the back seat of the car before sliding behind the steering wheel and cranking the Chevy and scratching off.

Now, a half hour away from Graceville on the return trip, they were wobbling down the road as the car radio hummed with the Platters’ Greatest Hits. Stud was stripped down to the waist, taking in the sun, half awake and leaning against the door while Dixie drove.

“I sure love those Platters,” Dixie said.

“Humph?” Stud mumbled, jerking up straight.

“I said I sure love those Platters. Way they sing.”

“Bunch of niggers, if you ask me.”

“What’re you, one of them hillbilly singers?”

“Gimme a choice, I’d take Kitty Wells any day.” Stud yawned, stretched, sat up straight, and slipped back into his t-shirt. “Where’d you get the car? Hell, I ain’t even got a car. And that money you got out of the trailer. Them clothes.”

“I told you. When Daddy got killed. Insurance.”

“You didn’t even stop at the department store.”

“They know what they can do with their cashews.”

“Whhee-eww,” Stud said. “You’re something else. Goddamn banging on my door this morning and I said, ’Pussy posse.’ I figured it was half of Crestview coming after me, gonna leave me out on the road, nail up a burning cross, and take you back home. How many brothers you got? I mean big brothers. Bigger’n me.”

“No brothers,” said Dixie. “No sisters. Just Mama.”

“Yo’ mama big and mean?”

“Mean as shit.”

“Daddy’s dead.”

“Daddy’s dead.”

“How far we got to go?” Stud said.

“Where to?”

“Ballpark. Graceville. We got a game tonight.”

“I figure we’ll be there in twenty minutes.”

Stud tilted his hat and scratched his groin and lighted a cigar. “Whhee-eww,” he said. “You’re crazy as Talmadge Ramey. You know that? Talmadge is this goddamn queer that runs the ballclub. Drinks moonshine with tea at nine in the morning. Got three of the prettiest little boys you ever saw living with him in this big old funeral home. His mama lives in a wheelchair down there where they keep the bodies. Talmadge sells everything but autographed pictures of Jesus on the radio. But I tell you, Miz Dixie Lee Box Crestview, you beat anything I ever even heard of.”

“That a fact?”

“You’re crazy. Bona fide crazy, girl.”

“Well,” Dixie said, “us crazies gotta stick together.” She wheeled off the highway and dropped Stud at Oilers Stadium. “Play good, now, you hear?” she said. “I think I’ll just go tidy up the place. Try to get home early.” Before Stud could say anything, she had spun away in a cloud of dust.