She is small, and her hair looks terrible. Distressed. Long and ratty, a bad white-yellow with a greenish tinge (dark roots are struggling back), it appears to have fallen victim to one too many dye jobs. Blond Ambition takes its toll in more ways than one. She does not quite glow with health. Her less- than-perfect skin is pale and lightly powdered; her lipstick is dark red. She is wearing a cream-of-asparagus cardigan over a decollete blouse; an edge of gray-blue brassiere shows. Her trademark. Her chest is freckled. Her denim cutoffs are festooned with a nightmarish profusion of spangles, doodles, flags. On her feet are pointy turquoise mules. Madonna at home would have pleased Charles Addams.

Yet withal, she is a lovely woman. She could, you have the feeling, change clothes, do something with her hair, and look ravishing in five minutes. And she’s done it, a thousand times. Only she could bring it off. There is, first of all, that body. And her blue humorous eyes, which pierce and search. Her calm, measured, only slightly provocative presence. And her speaking voice, which sounds the way a pretty girl would sound over the telephone before you ever met her: subtle, teasing, with just a hint of brass.

She can say singular things with it, too. I met her once before, in passing, when an actor I was interviewing introduced me. The chirpy remark she made, at the actor’s expense, was as funny as it is unprintable. Today, however, she’s on her best behavior. Sort of. One does not enter Madonna’s home ground with equanimity, nor does she exude phony hospitality to unknown inquisitors. A certain tension hovers in the air, like sachet. We’re sitting in the living room of her home, atop one of the Hollywood Hills. The exterior of the house is rectilinear and severe; the terrain is steeply sloped and forbidding. This is reclaimed desert, after all: There are snakes, of many varieties, in these hills. Not to mention armed security guards. It’s not the kind of neighborhood you stroll through at night.

The inside of Madonna’s house is also severe, with the saving grace of a sexuality that reaches every corner of the sparsely but quirkily decorated place. The art is beautiful and eclectic but, like its owner, dark and challenging. A consistent theme, in paintings, photographs, and books, is the female nude. One remarkable black-and-white photo, prominently displayed in Madonna’s office, superimposes the outline of a cross on the naked posterior of a woman.

“That’s a Man Ray — that butt right there,” Madonna says, as she shows me around.

“That’s great,” I say. ”He really foresaw…”

She finishes my sentence for me. “My future,” she says.

Madonna Louise Veronica Ciccone — a petite Italian/French Canadian brunet out of Pontiac, Mich., with gapped teeth, badly bleached hair, and a mole on her upper lip — appears to unsettle us inordinately. How does she do that? Hard to say. Precise definition, in any case, would diminish her omnipresence. And her longevity. A public figure, any public figure, is Scheherazade. The moment she ceases to interest us in her story, she’s dead. (Where have you gone, Cyndi Lauper? Debbie Harry?) Madonna has lasted far longer than 1,001 nights (it’s been eight years now, a pop-culture eternity) by never repeating herself, never pinning herself down. Were she a more than effective singer-songwriter, she would somehow matter less; were she a great movie star, she would not impinge so on our dreams. And now here she is in a movie that will probably lift her star above the zenith.

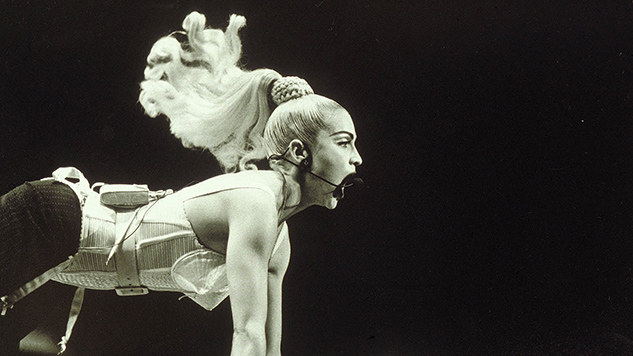

Truth or Dare, opening nationally this week, dares to presume that a great many of us are sufficiently fascinated by Madonna to want to watch a two-hour quasidocumentary about her last tour, the one entitled Blond Ambition. It appears very likely that, as has almost always been the case with Madonna, her presumption will guarantee our interest. The movie takes its title from a party game that Madonna and the rest of her group played while relaxing on tour: It is a game of psychic (and sometimes physical) disrobing, and the title’s conceit is that the star is engaging in a similar self-revelation by appearing in the film.

It’s a strange and complex move. The very form of the movie is presumptuous: Documentaries are usually a type of journalism, in which the filmmaker has some kind of objective distance from the subject. In this case, the filmmaker, 26-year-old music-video director Alek Keshishian, was hired by the subject; some rumors had the filmmaker literally in bed with the subject. At the very least, he was a big fan. Madonna herself put up the money ($4 million) for the project, and served as its executive producer.

And yet the movie’s dark and often unflattering vision of its own star makes it more than an exercise in vanity. Or does it? If there’s one thing Madonna’s always claimed to be, it’s an artist: Now she seems to have latched onto the extraordinary idea that not just her image but her life itself can be art. It’s a facile, open-ended aesthetic, one in which no excess is out of bounds. But excess has always been right up Madonna’s alley. The gamble she’s taking here is that she might — heaven forbid — bore us.

The books—provocatively placed? — on the coffee table between us are Jeux des Dames Cruelles, by Serge Nazarieff, which would appear from its cover to be a history of spanking, and two books by the French photographer Bettina Rheims, whose pictures of women are harsh, raw, and erotic. Directly overhead, fixed to the ceiling, is a huge 19th-century French oil of a nude Diana with an unclothed Endymion — the only naked guy in the place.

“It’s something that I felt compelled to do,” Madonna says of Truth or Dare. “I was very moved by the group of people I was with. I felt like their brother, their sister, their mother, their daughter — and then I also thought that they could do anything. And that we could do anything on stage.

“Because the show was so demanding, so complex — whenever you go through something really intense with a group of people it brings you closer together. And ultimately, though I’d set out to document the show, just to get it on film, when I started looking at the footage I said, ‘This is so interesting to me. There’s a movie here. There’s something here.’ ”

“Her life is all about staying in the public eye, and staying revered and needed and desired.”

Much will be made of the psychodrama within the tour’s all-male dance troupe, all but one of whom is gay. But the most highly charged passages in Truth or Dare revolve around (who else?) Madonna herself. One is a brief tête-à-tête between the star and her close friend, actress Sandra Bernhard; the two were the subject of much buzzing a couple of years ago when a coy joint appearance on Late Night With David Letterman seemed to hint there might be more to their friendship than friendliness. In the movie Madonna tells Bernhard how, as a little girl whose mother had just died, she slept in her father’s bed; she then makes an unsettling joke about having sex with him. (“It’s a joke, for God’s sakes!” Madonna protests to me.) This, in turn, leads to more sex talk. Madonna: “Are you still sleeping with her?” Bernhard: “I hate her.” Madonna: “I hate everybody I sleep with.” Bernhard: “That’s why you sleep with them.” Bernhard asks who in the world she’d most like to meet. Madonna says, “I don’t know. I think I’ve met everybody.”

This is, of course, a cozy meeting between two visible participants and four unseen ones: camera, light, sound, and director. And as is the case throughout Truth or Dare, there are several levels of meaning at work, some intended and some not, many ajar with each other.

The star seems perfectly comfortable with the contradictions; her friend does not. Bernhard, a powerful, abrasive presence onstage, a wonderful actress when the situation calls for acting, seems shy, ill at ease. Is this an intimate meeting between friends or a movie scene? If it’s a movie, where is the script? If it’s a documentary, where’s the reality?

Now I mention the scene to Madonna, and say that one charge her critics have consistently made is that she lacks vulnerability. “It seemed to me,” I say, “that even in those moments in the movie when you would appear to be most vulnerable, you’re so in control.” She folds her arms. “Uh-huh.” I tell her I thought Sandra Bernhard had the look, in that sequence, of a civilian.

“And I didn’t?”

“Not for a second.”

She laughs nervously. “What did I look like?”

“You looked like Madonna,” I say.

“And I’m not a civilian?”

“I can’t imagine you being a civilian. Now, that may be my failure of imagination.”

“It is,” she says. “I think that you’re suffering from what the mass population suffers from — once you put somebody on a pedestal, you can’t see them any other way. I think you should watch the movie again. I disagree with you.”

”I’m glad you do.” ”Because you would hate to think I was invulnerable — is that what you were going to say next? I don’t think one can get through life being invulnerable.”

Nevertheless, I say, her strength is formidable.

”Well, you better be strong if you’re gonna be in this fight — that’s all I can say.”

That superstars are embattled comes as no surprise. But few have girded themselves this well: You have to look hard to find signs of Madonna’s vulnerability in Truth or Dare. Still, in revealing her toughness, the movie appears to have gone further than even she expected.

“I think she didn’t understand what she was getting into,” Bernhard says, later. “Her life is all about staying in the public eye, and staying revered and needed and desired. Her addiction to attention is so intense that she’ll go to any lengths to get it — to the detriment of her sanity, and of her soul, sometimes. It’s not necessarily an admirable trait.”

“Does anyone talk about how crazy this is?” Warren Beatty says, on-screen and mid-tour in Truth or Dare, while Madonna has her severely taxed larynx examined by a doctor.

“Is there anything you want to say off-camera?” the doctor asks Madonna.

“She doesn’t want to live off-camera, much less talk,” Beatty says.

(Madonna says she felt Beatty didn’t take Truth or Dare seriously while it was being made — “He just thought I was making a home movie” — and hasn’t seen it. “I think that his agents and his publicists and people close to his lawyers — they’ve all seen it,” she says. “And basically reported back to him that he’s okay in it, that it’s not a debacle.”)

Madonna herself appears to be calm, even happy, about her movie. Or maybe it’s just that she’s girded herself yet again. “I think she’s very nervous,” Bernhard says. “I think she’s bitten off more than she can chew. But I’m sure that on some level she’s bored; she has to do something to scare herself.”

But how high was the high wire? Was there a safety net underneath? Who had final cut? “Madonna was the executive producer, okay?” director Keshishian says. “But I think by the time we finished shooting, she respected my autonomy. Still, you have to understand, I really did look to her for her input, which was not based on vanity or self-protection, but on the correct pacing for the movie.”

We’re sitting in Alek Keshishian’s cubicle at Propaganda Films, the production company he joined after directing music videos for such stars as Elton John and Bobby Brown before he got the big call. It was a call Keshishian had waited a long time for: He’d avidly followed Madonna’s career while he was at Harvard — where she wasn’t exactly a popular taste — and included songs from True Blue in his senior thesis, a very up-to-date theater translation of Wuthering Heights.

“I’d seen a lot of his videos,” Madonna says, smiling. “I’d seen him around in nightclubs and stuff. I liked the people he was with; I liked the way he looked; I liked the way he danced. I knew he was educated. And I felt that I had something in common with him. So — I just called him.”

Keshishian is handsome and intense, with big, close-set brown eyes and dark hair slicked back in a ponytail. He smokes steadily, and speaks with a world-weary rasp that makes it easy to forget his age. (At one point in our interview, I ask him how much more time I have. “Till you keep me interested,” he says, exhaling smoke.) On the walls behind him are a still from A Hard Day’s Night and a large calendar for May, with ”Cannes” printed over the week of the 13th.

“Is Truth or Dare a documentary?” I ask.

“I would consider this more of an emotional documentary,” Keshishian says. “The overall effect certainly is to document what the tour was like. And there was a very fine line between allowing reality to happen as it were to happen, and pushing it to the limit, where at times you try to manipulate the confrontation between people.”

“So some things were manipulated?”

“Sure. I mean, there was stuff like Moira McFarland.”

Her power can’t be denied; only her artistic intent is puzzling. By applying her image-making skills to what appears to be her actual life, she has passed into anxious new territory.

When, during the Japan leg of the tour, Madonna mentioned her childhood friend on camera — “the girl who taught me how to stuff my bra, insert a tampon and French kiss” — Keshishian looked up McFarland, a housewife and mother in South Carolina, and put her in touch with Madonna. When Blond Ambition went to Washington, D.C., Keshishian brought McFarland to town and, without telling Madonna, placed her in the hotel hallway so that the star would encounter her on her way to a sound check. Then he turned on the cameras.

The result is painful and complex. McFarland is eager for this reunion — she presents her friend with a painting — but says Madonna hasn’t answered her letters. The bushwhacked star seems distracted and chilly. Then McFarland makes a dramatic request: Will Madonna be godmother to the child she’s carrying? Madonna hedges, then leaves.

Their parting is awkward. “Goodbye, Madonna,” McFarland says. “Goodbye, Moira,” says Madonna. Moira, under her breath: ”You little shit.” Later, in her room, Madonna makes fun of the painting Moira has given her.

“She was still really a stranger, in a lot of ways,” Madonna tells me. “My concentration is on the show. I couldn’t really sit down, and I knew she was feeling very vulnerable, and she asked me to do something which was very flattering and very personal, and it really took me by surprise. And you can see — I absolutely don’t know what to do. And I think probably I come off as being cold.”

“Madonna grabs my arm when we see that scene together,” Keshishian says, with satisfaction. Indeed, the moments he manipulated are the ones that show her at her most vulnerable or unattractive. Scaring herself — and risking our alienation — all seem to be part of the high-stakes gamble.

Despite Madonna’s initial pull toward her director, she was brusque with him when he and his crew first joined the tour in Japan-probably because neither he nor she had any idea what he should do. For all anyone knew, this would be a standard rock documentary. Only when the first rushes were shown did it become clear what the picture might become. And only when Keshishian, brusque in return, demanded his crews have unlimited access to Madonna’s life did his star warm up. He had found his idol’s preferred mode: tough love.

Both he and Madonna claim they were never romantically involved; in any case, it’s clear where their mutual passion lies. “Madonna and I share a very similar viewpoint on the way one can use image in an artistic yet also commercial light,” Keshishian says, dead serious. Truth or Dare is a jointly conceived, barbed-wire valentine, crafted by two media wizards: one who often seems to need a male muse to goad her vision from her, one who needed his heroine to stimulate him to his best work. Their joint calculation can lead to weird results. In what might have been a pivotal emotional moment, Madonna makes a rare visit — for the cameras — to her mother’s grave. (Madonna Fortin Ciccone died of breast cancer at 30, when her daughter and namesake was 6. “She’s still running from it,” Sandra Bernhard says.) It becomes another manipulated moment — a photo opportunity taken to wrenching extremes.

“That’s the one place where it’s such a private moment that the sheer act of capturing it on camera is gonna give you that sense,” Keshishian says. “I had my crew go there earlier; we hid a microphone in the ground. She didn’t know she was being miked. There weren’t wires or anything. What we tried to do was put the cameras behind trees and stuff.

“When that graveyard scene was done, I was in the car with her, and she was very moved. It was an exorcism for her. And no matter what anyone says, I think there are glimmers of truth, and loneliness, there. It might have been more emotional if the cameras hadn’t been there; it might’ve been less. All I can tell you is that it was emotional for me watching it, there behind the tree.”

Says photographer Herb Ritts, her longtime iconographer: “The first time I worked with her was when I was doing the poster for Desperately Seeking Susan. She marched in with this little cigar box full of jewels and trinkets that she wanted to wear. She knew exactly how she wanted to look. I liked that. She’s very open to trying and doing.”

As long, that is, as she has significant control of the process. Where Madonna’s ability to enthrall has fallen short has usually been when she’s stepped into other people’s projects. The problem is that movie acting — perhaps her highest ambition — is usually someone else’s project, by virtue of the sheer capital involved. And the essence of acting is not just command but surrender. How could this woman ever surrender?

“She once came in and read for me on a picture I was doing,” director and actress Lee Grant says. “This was just after Desperately Seeking Susan. And she was wonderful — open, alive. She cried during that reading. These days she’s so busy packaging herself that she’s covering whatever she had. She had talent, and she closed up like a clam.”

I mention to Grant that some of Madonna’s recent glamour photographs, as well as her performance on the Oscars, have made reference to Marilyn Monroe. Should we compare icons?

“She hasn’t a clue to what made Marilyn Monroe,” Grant says. “It was vulnerability. What she is is Jean Harlow.”

But this doesn’t seem exactly right, either. Harlow was soft, if brassy, with an easygoing, wisecracking sense of humor. The Madonna we see in Truth or Dare — with her hard, sculpted body, her ritualized stage posturing, her tough-mama act behind the scenes, and her willingness to let it all be filmed — isn’t quite like anyone else, ever.

“There’s a moment at the end of Truth or Dare,” I say to Madonna, “when you and your dancers are all in bed together, and you all say, ‘Do we care what Hollywood thinks?’ And everybody shouts, ‘No!’ Is that true of you?”

She shifts in her chair. “I think that’s our way of saying, Well, we just filmed some crazy stuff, and if they don’t like it, we don’t care,” she says. “I mean, we were being silly to a certain extent, but I know that a lot of the things I do are not necessarily accepted. Even by Hollywood.”

“But there’s this whole question of your movie career.”

A silence you could slice. “Mm-hmm,” she says.

“Which has had its ups and downs.”

“Yes.”

“And which you seem to be planning to keep going.”

“Yes — because I would like to make some good movies. But just because I want to be good doesn’t mean I want to conform.”

I’m curious if she has any role models in mind. “Who’s been good without conforming?” I ask.

The answer is instant. “Me.”

She is, those close to her say, a sweet girl, a romantic at heart, who loves to make spaghetti in her kitchen for friends. She is also, she admits, an “emotional cripple. I’m not a completely evolved, whole human being.” This would certainly account for some of the less pleasant parts of Truth or Dare, as well as for her outsize ambition.

But we should keep in mind how little we tolerate ambition in women. It’s easy, in Truth or Dare, to see Madonna as a cold, domineering, emasculating mother to her dancers — yet as Vincent Paterson, the tour’s choreographer and codirector, points out, the road creates unimaginable pressures, and the star is also, after all, an employer. It’s also easy to see her, throughout her career, as a demon of calculation, inventing and reinventing herself at exactly the right moments. “I’m very flattered that everyone thinks I’m such a good businesswoman,” she says. “But I think that to say that I’m a great manipulator, that I have great marketing savvy, is ultimately an insult, because it undermines my power as an artist.”

Her power can’t be denied; only her artistic intent is puzzling. By applying her image-making skills to what appears to be her actual life, she has passed some point of no return and moved into anxious new territory: How, after this, could she ever give us less? It’s remarkable how the calculated provocativeness of the Blond Ambition production numbers in Truth or Dare, in color, pales next to the black-and-white footage of what went on off the stage: She has outdistanced herself that fast. Now the ante seems impossibly high. In the nine months since her tour ended, Madonna has brought the state of her art — whatever it is — to a new level. She’s found her true medium at last: This is her greatest, her only, role.