Los Angeles is in the middle of a heat wave; the Santa Anas are blowing in off the desert and the air is hot and dry even here in the Forum, where tonight the Lakers are up against the run-and-gun San Antonio Spurs. Third-quarter action. Earvin Johnson, the Lakers’ 6-9, 20-year-old rookie—the Point Guard as Big as the Ritz—has the ball. He comes down, gets it in to Kareem, goes back door and gets it back, goes up and can’t find the tree line. There is no shot over the outstretched arms of two San Antonio defenders, no place to go except down. He switches hands, moves his left wrist, and the ball comes out on the other side of the forest, back in the hands of Kareem, who drops it in gently off the glass. A breeze rustles through the Forum.

The Spurs come down, miss. Kareem gets the rebound and makes the outlet pass to Norm Nixon. Nixon finds Johnson at midcourt, in traffic. He steps around one man, doodling with the ball, wide-eyed but unconcerned. Misdirection. Peeking back at Jim Chones sprinting up the floor, he steps over the three-point line with the ball in his right hand and scoops the ball back to his left, to the breaking Jamaal Wilkes, for a no-bounce lay-in. Just winks, drum-thumping for the marvels to come later, the ones worthy of the packed house and enthusiastic applause. Intimations.

A week before, against the San Diego Clippers: Kareem tips to Nixon, who fires to Johnson. He is off and running in that peculiar gait of his, like an arthritic stork, driving hard on Lloyd Free. Nothing pretty here, just confidence and determination—get the first basket. Giving away six inches, Free shadows him in, conceding the lay-up, hoping for the cheap steal. Johnson, leaning, pulls up and shoots the awkward elbows-out jumper he learned at Michigan State. The ball banks in from 10 and, thrown off-balance, Free fouls. The announcer blares, “Basket by Earvin Magic Johnson,” which is what they call him out here on the Lakers.

Magic is their sky pilot, the point guard whose passing game and enthusiasm have helped rejuvenate a bland, stale team. In the warm, often languorous world of the NBA, he is a bright, hard metallic note.

A Saturday night in March in Seattle, the Lakers’ last regular-season match-up against the world-champion Sonics. The game is a struggle for purchase, king of the hill played at speed. A recurring image: Magic rips a rebound off the defensive boards and comes shooting out of the backcourt. John Johnson cuts off his lane, bracing for the charge, but Magic pushes the ball behind his back and is gone. There is no one that tall who can do that; if you saw, say, Maurice Lucas do that, you would smile and shake your head. Jamaal Wilkes grabs Magic’s behind-the-back pass in midstride and lays it in, and the ball doesn’t touch the floor. The Lakers win, 97–92. Magic is their sky pilot, the point guard whose passing game and enthusiasm have helped rejuvenate a bland, stale team. In the warm, often languorous world of the NBA, he is a bright, hard metallic note. Magic Johnson speaking:

“It was nice, because the people get off on you. Either you’re good or you’re no good. Either one or the other—you can’t be in between. You can tell when you’re no good because the crowd will be blah. They’ll be standing there. But if you got them dancing all the time, that’s when you can tell. That’s a big part of me. My music.”

Magic, his music. At Michigan State, he had a regular deejay gig at Bonnie and Clyde’s, a Lansing disco, and when the set ended, there he was, standing up to say there was a game Saturday over at Jenison Field House, and everybody should come on over. “I play to a beat,” says Magic.

EJ the Deejay, doing it for love. The Big Fun. But the fun comes after the main thing, and the main thing is the winning. Short reviews from some tall people—the toughest audience in the world: “He’s a great all-round player and a better passer than I am, no doubt,” says Larry Bird, the player everybody makes into Magic’s rival and a fellow 7UP drinker. “He has the enthusiasm and the hustle to be the greatest ever.” Elvin Hayes: “The way he brings out the best in a team reminds me of Dave DeBusschere, Bill Russell, Bob Cousy, Walt Frazier….” “He’s exciting in all ways,” says Dennis Johnson. “Magic does exciting things. The Hop, the No-Look, the Hesitation….” Bobby Knight: “There isn’t anything singularly impressive about Magic Johnson. He’s encompassingly impressive.” George Gervin, an old Magic backer: “He hasn’t surprised me. He can score big when he wants, and he makes the team look sharp.” His future, says another old friend, Julius Erving: “Unlimited.”

Magic remembers Lansing days, chapters in the making of a basketball player: “I’d get to the playground and somebody would pick me for his team. But before I would decide, I’d ask him who else was on the team. If he had Johnny Doe, who leads the city in scoring, and also the next leading scorer, I would say, ‘No.’ I’d wait and ask the next guy who he had and if he said he only had me I’d say, well, me and you and get Sam, a good rebounder, and John, a good defensive player. Then we would have a good mix; we’d have a team.

“You get all those big scorers or the one-on-one players and the game breaks down: Everybody gets mad because one guy’s trying to show off for all the women. But the team that was a team always won. My team won all the time.” Everybody he plays with just gets better. A cold, tough claim to stake, maybe, but the numbers are there, blinking a relentless staccato that flashes WINS.

Lansing Everett High was 9–11 and 11–12, and then in the 1974–75 season along came Magic, who led it to a 22–2 record. There followed a 24–2 season, and then 27–1 and the state championship that George Fox, then the Everett coach, says he thought they’d win at least two of the three Magic Years.

Fox is a square-built, kindly man who quit coaching the year after Magic left, when his 22–2 team—four starters back—lost in the states. The next year Everett went 7–15. He remembers Magic’s senior-year team had a lot of pride—“Pride in its defense. Some teams like to trade baskets, but not that one, Buddy. I’d say, ‘No lay-ups!’ and we’d give teams the baseline, Earvin would block their shots and away we’d go.” George Fox smiles, remembering that last championship season. “When he was a senior he was averaging 44, 45 points a game the first four games, but we weren’t playing good ball. I said, ‘Earvin, if you want to win the states, I think you’d better average about 23.’ He said, ‘I got you, Coach.’ That was all I had to say. I think he averaged 23.8 that season. It was almost like he had it programmed.”

Michigan State and Jud Heathcote had gone 14–13 and then 10–17 when they won the intraconference, intrastate battle for the rights to Magic. “Johnny Orr, then at Michigan, said, ‘Foxy, do you know what I would do for that kid?’” laughs Fox. But, all other things even, Earvin Sr. leaned crosstown toward State, where Greg Kelser and others were tuning up. Magic was the maestro, and on winter mornings in places where they take their basketball pretty seriously, places like Bloomington or West Lafayette, people would get up and rub their eyes and see that the Spartans had won again. In Magic’s first year they went 25–5, finally losing to NCAA champion Kentucky in the finals of the Mideast Regional, 52–49. The next year they were back and, despite a January slump, out at Jenison everybody knew the W’s would come, and then it was the roses for Heathcote and the Lakers for Magic. This fall, Jud Heathcote became the first coach to win an NCAA championship, to get three starters back and not be ranked in any poll. Michigan State fell to 6–12 in the Big Ten. “I knew he could start for any club in the NBA,” says Heathcote now. “But I’m surprised he’s scoring as high as he is. I thought he would concentrate more on his playmaking.”

He had first turned up in Los Angeles in the middle of last summer to play in a summer-league game, and 3,000 people turned out. They got a show, and when it was over Magic was inviting the crowd out to the Forum in the fall for the real thing. It would be, he said, real interesting. In October, the Lakers won their first game against the Clippers 103–102 on a last-second skyhook by Kareem. As the ball dropped through, the somewhat startled Jabbar found Magic—who had scored 26—in his arms, hugging him. Do it for love! There was a new kid in town.

He is a child of television—it was television that made a star out of Magic, that showcased him in last year’s NCAA tournament. Television is for Magic Johnson.

It is easy, because of the hand-slaps, his obvious joy in the game and the grin that leaps out at you, to dismiss Magic as a hipper, latter-day Say Hey Kid for the post-disco eighties: When the klieg lights go on, it’s showtime. In a three-minute round with two minicams and four microphones, he can hang with the best. Mike Douglas had him on the show, and no request was too silly—all right, says Mike to Danny Thomas, Neil Sedaka, Helen Reddy and Magic, now we’re going to see who can pump up this here flat basketball the fastest and bounce it waist-high. And Magic won and obviously had a good time winning. He is a child of television—it was television that made a star out of Magic, that showcased him in last year’s NCAA tournament. Television is for Magic Johnson. And he seems to be fairly comfortable in the public persona of good old lovable EJ, coming up for 7UP. But it’s a mistake not to look behind the commercial. Always polite, there are times when the skin at the corners of his wide-set oval eyes tightens, and you see the hardness, the maturity there. Magic brings a healthy dose of Midwestern cynicism with him, what used to be called horse sense. Court sense. Don’t go for the first fake. See the entire floor.

It’s a new/old idea, the athlete as lunch-pail kind of guy. Be serious. Pick and rolls, not mink and Rolls, not Clyde or Broadway Joe. Magic is obviously intrigued by the likes of Jack Nicholson at courtside but at the same time he has a job to do, not unlike his father back at the plant. This year he had a chance to be on The White Shadow, but it would have interfered with the game, so he let it pass.

Yet there is an almost touching naiveté about him—this kid who came to the Coast and listed his telephone number in the book, just in case anybody wanted to call him up. He went to school 10 minutes away from his mother’s table, and this is his first real experience away from home. He doesn’t know Los Angeles well, doesn’t go out much.

“Hollywood,” he says. “I haven’t checked any of it out. When I go out, I just go out—and have some fun. Not everybody’s there to have fun, though. Everybody’s there to be—I’m here, you know, and I be there to dance and dance some more. But they just be standing there. Shhh….”

Still, there’s time to conquer the cameras—smile for the pretty girls—but you do it on your time, made time. Earlier in the season, press demands on Magic were so disruptive the Lakers instituted a special press conference in each new city they visited, just for him. In Madison Square Garden the cameras were rolling, the questions came, including the one he is asked most—what about the transition to the pros from college? How would it be different if he were back in Lansing?

Magic blinks. “Wouldn’t be three-and-five in the conference, I can tell you that.” He smiles. EJ, the Point Guard as Big as the Ritz.

The drive into Lansing takes you through cold farmland that stretches almost to the very edge of town, a small city dominated by the auto plants, the machinery of state government and Michigan State over in East Lansing. A gray town, marked off into neat blocks of frame houses, like the one Earvin Johnson Sr. settled into 25 years ago, after coming up north from Mississippi. He moved into a hotbed of basketball talent—“Best players in the world come off the Michigan playgrounds,” says a partisan George Gervin. “That’s a shooter’s world up there.” Gervin, Terry Furlow, Ralph Simpson, Spencer Haywood and others had played in northern Michigan, and it was on those playgrounds that Earvin Johnson’s son made a name for himself.

In 1974, Fred Stabley Jr. was a young sportswriter covering high school basketball for Lansing’s State Journal. “The first game Lansing Everett played that year, they got by Holt by a point, and Holt wasn’t very good. Earvin was 6-5, 6-6. He was average. Then I saw his next game and I never saw anything like it. I think he had 36 points, 18 rebounds, five steals, 14 assists; it was against Jackson Parkside and they were supposed to be one of the best around. I went down and I said, ‘Man, Earvin, that was something else. We got to call you something.’ And ‘Dr. J,’ that was taken, and ‘the Big E’ was, too. I said, ‘How about Magic?’ And he said, ‘That’s okay with me.’”

Magic. George Fox never called him that, but he thought he had something. “I knew him when he was in junior high. He was about 6-3, skinny as a rail, liked to stand outside and shoot. One day his brother came by and said, ‘Hey, Coach, Earvin says to come to the game today. He’s going to set a junior high scoring record.’ I went. He did.

“By the ninth grade he’d grown an inch, he was 6-4. We knew we had a good player coming, but no sensation. We had set up a summer program and we played Haslett. At the end of the third quarter we were ahead 33–5. People said he was further along in 10th grade than Ralph Simpson had been. I said he’d make people forget Ralph Simpson.”

The Lansing school district was in the middle of a busing dispute; Magic should have gone to Sexton, over by the Fisher plant on the west side, but he ended up at Everett, then thought of as a white school. In the early ’70s, there were some racial troubles that nobody wants to talk much about, and they touched Fox, who had a reputation as something of a disciplinarian. One of Magic’s brothers was on the Everett team, and when he missed a Christmas-vacation practice, Fox kicked him off. The brother swore Magic would never play for Fox, but in the 10th grade there he was, and there Everett went, losing in the semifinals of the state tournament when they blew five one-and-ones in the last minute. Some people suggest that with that team—three white starters, two blacks, plus Earvin Johnson’s personality—the racial problems in Lansing began to cool down. By the time they won the state championship in 1977, those troubles were in the past and there was just the recruiting to deal with. Magic narrowed his choices to UCLA, Maryland, North Carolina, Purdue, Indiana, Michigan and Michigan State. He was a force in Lansing, and when he decided to stay it was as if a municipal treasure had been ransomed.

“The Magic years,” Fox says, “were a lot of hard hours. He was just like a big kid, and I didn’t want anybody to hurt him. His family meant a lot to me. Maybe if his mother and father were wheeler-dealer types, I wouldn’t have cared.”

Life was good for Magic. The summer between eighth and ninth grades he met Terry Furlow, then an incoming freshman at Michigan State. He got into faster and faster games with Gervin, other pros. He was 13. “Furlow took me under his wing, you know. When they’re older and you get to hang out with them, meet people, date girls, that’s fun. The way I lived, coming up, I always had fun. That’s all I wanted to have, was big fun. If I left tomorrow, died or something, I’ve enjoyed every bit of it. It’s been cool.”

Meanwhile, Earvin Sr. was setting a higher standard for the work ethic, putting food on the table for his 10 children. For the last 23 years, Johnson Sr. has worked at the Fisher auto-body plant in Lansing. For most of that time he drove his own garbage truck, and some other years he pumped gas to make ends meet, while his wife, Christine, worked as a supervisor in a school cafeteria. “Some black athletes don’t have any direction,” says a friend of the family. “Magic had all the direction in the world.”

“He always hoped we’d do something in life, you know,” says Magic of his father. “He didn’t want me to ever join him, hammering them bodies. He wanted something better for me.” If the kids wanted to go to college—Magic and his sister Evelyn, the Sweet E, on a basketball scholarship at South Carolina, are the only children with enough athletic talent to pay their way—Earvin Sr. made sure there was money. He is a big man, about 6-4, and quiet. Another family friend says, “Once you’ve met Earvin Sr., you don’t know if you’ve met him.” The impression he leaves is one of strength, and there is obviously a bond between him and his youngest son. They would sit together on Sundays, watching the NBA game of the week—Earvin Sr. had been a basketball player back in Mississippi—and the father would analyze what was going on, why this happened and why that happened. Despite his work load, Earvin Sr. rarely missed one of his son’s games. With the help of an understanding supervisor, he always got a couple hours off on the nights Magic was playing. “If we wanted something, he always got it to us, you know, and what happened is, him and her didn’t get much.” Magic has spent some money trying to turn that around; he bought his mother a new car and his parents a new house—which his father grumbled about, claiming that the old house was good enough for him. Magic laughs. “My dad was a really big influence on me. He doesn’t play me up, he’s just regular. He’s the same old man, you know, does the same old thing.”

The other side of Magic’s personality comes from his mother. A devout Seventh-Day Adventist, Christine Johnson is shy and reserved in front of strangers. But as Magic says, “My mother likes to have fun. She loves to talk, and I got that from her. She likes Kareem, talks to him a lot. She’s really outgoing—I mean, invites everybody to dinner, cooks. Like, all our boys, we get on off the court, we just come over to the house, and she just get out the big pot.”

There were always people who cared. Greta Dart was Magic’s fifth-grade teacher. When the kids needed an adult supervisor to get into the gym, her husband, Jim, volunteered and became Magic’s first coach. The Darts are fans of, in this order, Magic Johnson, Michigan State and Jud Heathcote, and basketball in general. In his forties, Jim Dart still plays in a Lansing league. Childless themselves, they took an interest in the young Magic, found him summer jobs, sent him to basketball camp. And generally wished him well.

They talk about young Earvin and the pride is in one of their own. “I hired him to mow the grass once, and I assumed it was getting done because I could hear the mower,” says Jim Dart fondly. “And when I looked, there was the mower going around in circles at one end of the yard, and Earvin at the other, talking to somebody.”

Dr. Charles Tucker is a psychological consultant to the Lansing school district, and he became Magic’s main man. He played college ball at Western Michigan and then briefly with the old Memphis Tams, where he became friends with people like George Gervin and Julius Erving—people who were of no little help to Magic when he was considering going hardship. “The reason George, Julius, people like that, look up to me,” says Tucker, “is that when I got cut by the Spurs, I just went on back to school and got my degree.” He is smart and tough, and when Earvin Sr. needed advice, Tucker was there. Tucker helps Magic find his way through the sometimes-trying vagaries of a pro athlete’s life, especially trying if the athlete is 20 and away from home for the first time. And, excepting the occasional airline ticket, he does it without pay.

“He was at Everett High School, once I got there, and we played a lot of pickup games,” says Magic. “We just started hanging out.” Fox is clearer: “Earvin Sr. needed somebody like him. During the racial stuff, Tucker told the black kids, ‘Hey, this guy Fox knows basketball and he’ll make a ballplayer out of you.’ Tucker stands in the background, but he’s kind of a second father to Earvin.” It was Tucker who held Magic back when he wanted to go hardship after his freshman year at Michigan State, telling him the money would be sweeter the next year, and that, besides, there was the national championship to win. And Tucker did a large part of the negotiating on the Laker contract that will bring Magic somewhere around $500,000 this year. “I help Earvin sort through business,” says Tucker.

January. Dirty snow on the black tooth of Detroit. It was Magic’s homecoming—his only appearance in town this year—a Friday-night date against the Pistons in the Silverdome. The Lakers had set up an extra-special press conference for Thursday. The only thing was, nobody told Magic. Tucker had met him at the airport and off they’d gone while the local media fried under the television lights. “We don’t know where he is,” said an exasperated Laker official. “If you know where he is, tell us where he is.”

Tracked down in Lansing, about an hour and a half to the west, Magic’s response is direct, sure-handed. “Oh my God.” WJBK-TV flies to the rescue. A helicopter is dispatched, in return for a live interview on the six o’clock news, and the press conference goes off, five hours late. Detroit, with the Pistons, the Red Wings and the Lions in last place, and the Tigers an annual disappointment, does not have that much to cheer for. The Pistons expect a record crowd; it seems half of Lansing will be there.

But Christine Johnson won’t. The Seventh-Day Adventist Sabbath begins Friday at sundown, and she will leave the house only to go to church. Jud Heathcote won’t be there either; he’ll be down in Bloomington, watching the Green-and-White lose to Bobby Knight’s Hoosiers and probably wondering what if? The temperature has dropped. Out in Pontiac the wind collects grit and small pieces of gravel from the far edges of the parking lots that stretch for acres and whips them into your face. It is something like walking into a sandblaster, but 28,146 people have come to see Magic. George Andrews, Magic’s agent, has come up from Chicago. Greg Kelser, Magic’s teammate at Michigan State and the Pistons’ first-round draft choice, is here, sitting at the end of the Pistons’ bench with an ankle injury. And about 10 rows above courtside is a large square man in a reddish leather coat and a leather hat. Earvin Johnson Sr. is occupying one of the seats his son has reserved. “He liked Wilt, you know,” he says. “Wilt was who he wanted to be.”

Earvin Sr. barely looks up as the crowd cheers. Applause doesn’t make much of an impression on him; his concerns are more basic. The same old man. The same old things. “You know it made a difference,” he says of his youngest son’s money and celebrity, “but let’s just say this—it didn’t make me no bigger than I already am.”

He downplays his influence. “From the sixth grade on, I told him what I thought. When it came time to decide about the pros, I couldn’t say that I wanted him to stay or go.” He stares impassively at the raucous Michigan State fans around him and hunches forward so he can be heard. “It seemed like he couldn’t do no more there. They won the Big Ten, then they won the NCAA. After that, there didn’t seem like there was anything for him to do.”

Earvin Sr. is a proud man, but the pride is not for public consumption. He always sort of believed that if you worked hard enough for something you wanted bad you would probably get it in the end. Cramped in his seat, he is not an especially articulate man, but there is a look of satisfaction on his face. He says, “I believe in doing the right thing, not the might-be-okay-to-do thing. You know what I mean?” The national anthem is beginning, and Earvin Sr. is getting up slowly. He has one last thing to say:

“I never had no trouble out of Earvin.”

George Andrews is still regarding the upper deck, still going for the Green-and-White, minutes after the Laker victory, 123–100. “A show, wouldn’t you say?” he asks. Andrews, with his uncle Harold, represents Magic’s interests in the big-money circles. And those interests are considerable by anyone’s standards: Magic stands to double his Laker salary this year on endorsements. Harold Andrews is expansive, a Midwestern country clubber in Lacoste shirts and aviator glasses. “Earvin’s one of the best young businessmen in the country,” says Harold. “He’s a genius.” Nephew George is younger, plumper, but a little harder around the edges. They are outgoing but very discreet about their clients. They are even discreet about how they got to be Magic’s agents but, basically, they got to the final four, were invited to Lansing and hit it off with everyone. Chicago lawyers, they retain the less urban flavor of downstate. Conservative. Sincere. They represent mostly professionals and medium businessmen; the meat of Harold Andrews’ practice is with McDonald’s franchisees. Their few athletes—mostly Chicago or Michigan products, like the White Sox’ Lamar Johnson or the Pistons’ Phil Hubbard—have come to them on referrals from other athletes. They take pride in the fact that Magic is not nearly their single biggest client. Out in Los Angeles, George Andrews had spread his hands on a table in the Forum pressroom:

“He’s 19, 20 years old, and anything he does he’s going to have to live with. We’re getting him into some triple-A real estate, some blue-chip broadcast properties, some endorsements—you’ve seen the 7UP commercial?” Yes. Onward. “Spalding, Converse—hey, we’re talking with Oldsmobile. We said to them, ‘Look here, you’ve been putting bread on the table a long time, and we’d like to give you an opportunity to get some of that back.’” The details on that one hadn’t been finalized yet. Meanwhile, Magic has a brand-new Olds to park beside the requisite Mercedes. “—And we’re going to talk with some toothpaste companies in New York.” George Andrews leans across the table and says, “I want to represent Earvin’s kids when they are doctors or lawyers.” He notices a middle-aged white couple, and whispers, “the Darts. Almost Earvin’s second family.”

“I think Magic has led us. He’s playing the same game, but he’s getting smarter—throwing away the ball less. He’s just like me—l was never a rookie and Magic was never a rookie.”—Kareem

The weeks in L.A. just before Christmas were the worst, says Magic. “You can be homesick burned,” he adds gravely. The phone bills were running $375 a month, and finally he just gave up, called a few people, said come on out. Greta and Jim Dart came.

“Until this year, I’d seen every game Earvin had ever played,” says Jim Dart. He sighs. “It would have been nice to have him in Lansing another two years,” says Greta Dart. “I was hoping he’d stay one more year, let the Pistons draft him so we could get down to see him play some.” Her husband breaks in, “but we knew we’d lose him. When he went to State, he said, ‘I’ll stay till we win it.’” (Magic will say later, “I didn’t put it exactly like that.” He will smile.) Jim Dart continues, “We knew when he walked off the court in Salt Lake City, with that net around his neck, we’d probably lose him. He’s a fine young man, but let me tell you—any of his brothers would have handled it just as well. They were raised that way. When I had trouble getting on the charter to Salt Lake City last year, Earvin fixed it. We hadn’t been out here yet, and he asked us to come out. We’re staying at his place. How many of these guys would do that?” Dart stares. “And how many of them should?” He drops his eyes. “He’s going to outgrow us, someday,” he says, matter-of-factly.

George Andrews is on his feet. “Here he is. How you doing, Earvin? Great game,” he says, and Magic slides into his vacated seat, accompanied by Dr. Tucker. Tucker can be cool, almost to the point of surliness, then break it up with a smile. He is not smiling now. Magic is polite—he is too well-mannered to be otherwise—but there is that tightness around his eyes; the beginnings of annoyance. All he wants to do is get all these people from the Forum to his apartment in Culver City, and from there get something to eat.

This is, with Magic’s parents, his inner circle, and it is a different crew from what you might expect. There are strict, sentimental Frank Capra values in operation here, small-town talk, and it seems out of place in vanity-plated California, where even the weather is dramatic. The Point Guard as Big as the Ritz fills the Forum and gets his old friends out of a Michigan winter for a little L.A. sunshine. The one with his feet on the ground is king, or crown prince anyway. The crown prince has a restaurant picked out down by the Marina and insists that Jim Dart take the Mercedes—he’ll follow in George Andrews’ rent-a-car.

New York, just after the All-Star break. Third-quarter action, Magic with the ball. He throws it in to Kareem who waves it around, then zips it back to Magic, breaking. Lay-up, over Joe C. Meriweather. Chones fouls, but then Magic is fouled by Ray Williams. He makes one of two, then fouls Meriweather in the backcourt, a silly foul. The Lakers come down, Magic throws it in to Kareem and breaks, but Kareem, giving Bill Cartwright a lesson in how to play center, skyhooks it in. Toby Knight gets a tip-in for the Knicks, but Nixon hits one from the top of the key, Chones hits a baseline jumper and Magic comes swooping in from the left side and jams in one of Kareem’s misses. A nine-point lead has jumped to 17 in less than two minutes; where yesterday’s Lakers might have been content, complacent, these Lakers just keep coming. Nothing fancy—even a little sloppy—just power. Just boom. It illustrates the way they have jelled since September. With Kareem, Chones, Haywood and Landsberger and Magic at point guard, they can beat you into the floor. With Kareem, Wilkes, Cooper and Magic at power forward, they can finesse you to death.

Magic has been playing more at forward, to get Cooper into the lineup more often, and his scoring has dropped slightly, to 18 points a game. He still made the NBA’s top 10 in both assists and steals, and his 7.7 rebounds a game far and away led NBA guards. Magic is a fast learner; within the Lakers’ fast-break style he was quick to realize the mismatches his talent created. Others realized it, too.

“He has great court awareness, but what impresses me most is his intelligence,” says Dennis Johnson. “He recognizes situations on court very well. For any young player to come into this league and understand what’s going on as well as he does is amazing.” The intelligence is beginning to show in his defense—“Early on, they were eating him up,” says Bill Fitch, “but he’s made much better adjustments to defense from the beginning of the year.” Says Larry Bird, “Ah, they always talk about rookies and defense. If he does make a mistake on defense—which all of us do—he can come back and make some guy who has maybe been in the league nine years look bad.”

There are some pretty shrewd observers of the NBA who wonder what Magic would be like without the Lakers’ supporting cast. Atlanta’s Hubie Brown says, “If I had to vote today for rookie of the year, I’d go with Bird. Magic plays with supers.” But with Magic on the court, the Lakers’ supers play even more super. It is no accident that both Wilkes and Nixon, overlooked in the shadows cast by Kareem and Magic, are enjoying very good seasons. “I thought the Lakers had a great team last year,” says Fitch, “but they needed a couple of chemistry changes. With Chones and Magic they’ve really helped themselves.” The chemist might be Buss, but the chemistry is Magic. Tonight, in Madison Square Garden, they shoot 56 percent to New York’s 38, counter Knick surges with good defense, and win 116–105.

In the locker room, Magic is relaxed, smiling. “We’re becoming so close, man,” he says, “you wouldn’t believe it. All of them are showing their emotions now—Kareem is definitely fired up, smacking hands. We doing a lot of things, and that’s part of the team I want to be on.”

The Lakers are running smoothly, winding it out, tuning up for the playoffs. Magic, too; he is more collected than three months before, smoother. He is a professional. He sits for a long time, patiently answering questions, then ducks in for a quick shower. The Magic Line for tonight: 19 points, 10 rebounds, 11 assists. Not a bad night, even for the Point Guard as Big as the Ritz.

“Down to the wire, Magic wants the basketball,” Paul Westhead said. “He wants the loose ball in the lane, wants the follow. And he’ll put it in somebody’s face. It’s over for the rookie stuff.” And Kareem agrees: “I think Magic has led us. He’s playing the same game, but he’s getting smarter—throwing away the ball less. He’s just like me—l was never a rookie and Magic was never a rookie.”

Magic reappears, wearing a long fur coat over his red-blue-and-white satin All-Star uniform. “Catch you tomorrow,” he says. Magic Johnson is headed for Studio 54.

Tomorrow comes early, but at 10:30 Magic is sitting in Tucker’s hotel room, yawning over a cup of fresh fruit. Fifty-four was all right. He yawns again. Practice is at noon. He touches his head gingerly—last night he ran into Toby Knight’s tooth; three stitches. What about the Lakers?

“Color them dark gray,” wrote Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray, “the American Gothics of sport.” The American Gothics were 45–37 in ’77–78 and 47–35 in ’78–79, eliminated in the early rounds of the playoffs both years and playing increasingly uninspired basketball. Changes. The cover of the 1978–79 press guide shows an unsmiling, begoggled Kareem against a dark background, putting up a skyhook. The cover of the 1979–80 guide shows Kareem and Magic, numbers 32 and 33, smiling against the white pillars of the Forum. There are four players left from the ’78–79 roster—Kareem, Nixon, Wilkes and Mike Cooper, who spent most of the year on the disabled list with a bad knee. When you open the ’79–80 guide you find that seven Lakers who were around to get their pictures in it are no longer there. The list of Lakers who were lost this year and last is not inconsiderable—Adrian Dantley, Lou Hudson, Ron Boone, Don Ford. There is an important new name in the book, in fact, the first name—Dr. Jerry Buss, the team’s owner.

Jack Kent Cooke had built a team that usually won between 45 and 50 games a year, and the team was moody, bored and boring. One suspects that even Jack Kent Cooke was bored with them. Whatever, he had an extremely complicated divorce settlement to worry about, and when that was taken care of, he signed Magic to a five-year contract and rode off east to take charge of the Washington Redskins in person, having sold the Forum, the Lakers and the NHL Kings to Dr. Jerry Buss for $67 million.

A doctor of chemistry from USC who had made a $300 million fortune in Southern California real estate, Dr. Buss moved quickly to revamp the team. A trim 47, Dr. Buss has silvery hair, and he favors jeans and leather jackets cut to his belt line. He also favors pretty women who smile up at him adoringly. He is Western money, and there clings to him something of his native Wyoming—an arrogant cattle-baron look about the eyes. He realized quickly that to get to a player’s heart, you must first cut through his bankbook, and raises went out to the Lakers who were left, Nixon and Wilkes and Cooper. Importantly, the Big Guy got a new contract—about a million dollars and the Forum one night a year. More importantly, he got some help on the boards. Jerry West had a three-year coaching record of 145–101, for a .589 percentage, but he couldn’t get around the fact that the Lakers could not be successful playing two small forwards—Dantley at 6-5 and Wilkes at 6-6—alongside Kareem, a finesse center who takes an incredible pounding anyway. West’s record in the playoffs was 8–14. There, teams that played tough, physical defense had the Lakers’ number. Portland, with Walton and Lucas; Seattle, with Sikma and Shelton. When they came to town, it was push Kareem around and go to the boards. Dantley was exiled to Utah for Spencer Haywood. Jim Chones arrived from Cleveland—a big find since he can also spell Kareem at center. For the playoffs, the Lakers picked up rebounder Mark Landsberger, and while they were at it, veteran guard Butch Lee to steady their young backcourt.

Magic sits in the back of the bus and sings quietly. “Do it for love….”

West, who sometimes became frustrated with Kareem’s lackadaisical play, moved into the front office. The new coach was Jack McKinney, who had built a relationship with Jabbar as Larry Costello’s assistant in Milwaukee. Then, in a freak November 8 accident, McKinney fell while riding a bicycle, hit his head on a Palos Verdes curb and nearly died. His assistant, Paul Westhead, has performed more than capably in his absence; the Lakers were 9–4 under McKinney and 51–18 under their interim head coach.

“I think we got a chance to go all the way,” Magic says. “We’re working hard, you know, and we’re willing to do the things you have to do to get that far. But just working hard on the defense, that’s what’s going to get us there.” Another yawn. A smile. “We have big fun you know.” He is sleep-walking, giving the polished answers.

The head is bothering him. Magic had never had more than a sprained finger until the third game of the season, when he went down with a knee against the Sonics. He was scared, and even more scared when the Seattle team doctor told him, after a preliminary examination, he could be out six weeks. There was a chartered jet back to L.A., where Dr. Robert Kerlan assured him the injury wasn’t that serious. Magic was out nine days, but the memory lingers. He had never played more than 31 games in a season; this year he will play more than 100, and he was run down.

“I might be a little brittle, but that’s the way I play—as hard as I can. And I don’t mind taking the charges.” He smiles. “Goooddaaamn, I swear I always get hurt. I used to never get hurt; now I always get hurt.” Before the season started he said he hoped he could keep his intensity for at least 70 games of the 82-game season, and he thinks he has.

There is a knock at the door. Harold Andrews walks in and says, “Magic, I hear they’re biting you on the head.” It is time to go to practice.

Tucker is on the streets of New York City, with only a limited notion of where he is beyond that. Magic has an appointment with the toothpaste executives later, and he is out of shirts. Tucker has been appointed to buy him one.

“I like to take care of business,” he says, as store after store cannot produce a size 17½ black silk shirt. “Harold and George, they’re lawyers. They like to talk it over.” At Ted Lapidus, a suitable shirt is found, and Tucker is on his way up to 84th and Park, to the Loyola School, where the Lakers are practicing in a gym that can’t be more than 60 feet long, with a displaced P.E. class sitting in the bleachers.

Marty Byrnes, the Lakers’ fifth forward, is leading breaks against the gold team. As he crosses half court Magic yells, “Hey, Marty. Marty! Do it for love, Marty!” and, grinning, Byrnes stuffs. The kids are impressed. Do it for love ricochets with every jam. When the practice ends, they stream over for autographs, and then the Lakers head downtown. Spencer Haywood is playing tour guide, pointing out landmarks, the town house he is turning into condominiums. Jack Curran, the Laker trainer, says to Brad Holland, the Lakers’ other rookie guard, “That’s Bloomingdale’s, Brad. That’s where you want to come.” And so on. Magic sits in the back of the bus and sings quietly. “Do it for love….”

He laughs. “That’s just one of the sayings we have. See, coming to see us is like going to see the Jacksons. You’re sitting there, waiting—waiting on the show to get started.”

Idle chatter. Magic is going window-shopping later today, maybe buy a pair of shoes. But no status symbols. “I got the Mercedes because I always wanted one—not because everybody else in California is driving one, you know.” The flash of a smile. “I can’t go out right now, being big time.” There are a lot of stores to look at, says Magic. It’s all Big Fun.

“Like, being out with a special lady, going to dinner, or a movie, or the disco. Or just going out with the boys, hanging out, that’s the best time. Be there together—just talking about old times or going on the street corners again, singing at night in the summertime. You know, just reliving the old times. We had a lot of fun—me and my boys. We had a lot of fun. Leave the girls at home some nights and just go out ourselves, have a good time. That’s big fun to me.”

It should be remembered that Magic Johnson, christened by a sportswriter, is in the first generation of athletes to grow up seeing the pros interviewed every week on television, how they walked and talked and acted. That he had two very shrewd men, his father and Dr. Tucker, sitting on his shoulder, examples of hard work, telling him that he could be one way or he could be wrong. A cynic might say they told him what sells. But underneath the hype there is a brilliant talent and a gleaming innocence. Small-town values that sing at night in the summertime.

It should be remembered that Scott Fitzgerald, who knew something about at least the last of these things, wrote in The Diamond as Big as the Ritz: “‘I never noticed the stars before,’ said Kismine. ‘I always thought of them as great big diamonds that belonged to someone. Now they frighten me. They make me feel that it was all a dream, all my youth.’ ‘It was a dream,’ said John. ‘Everybody’s youth is a dream.’”

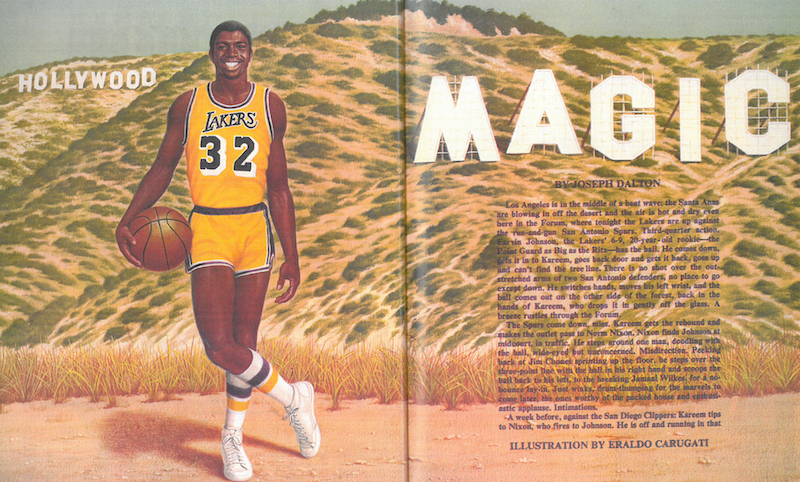

[Featured Illustration: Eraldo Carugati]