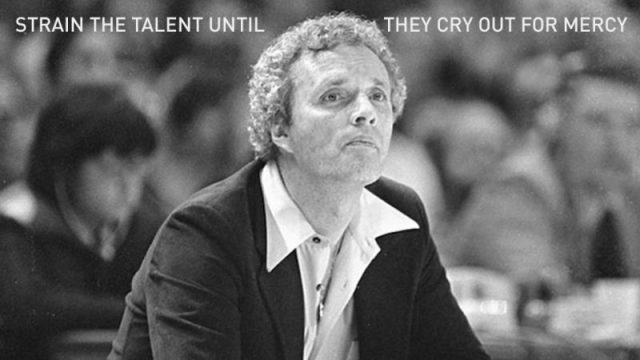

From a vantage point high in some structural-steel arena in a city like Philadelphia or New York or, for that matter, Atlanta, Hubie Brown, the coach of the Atlanta Hawks, appears to be a slightly mad martinet, a ranting, bantam dictator commanding an army of giants. Clad in a loud plaid jacket, a silken shirt open wide at the collar, double-knit slacks, and shiny black shoes, he stomps along the sidelines of the National Basketball Association cursing and screaming and throwing his hands over his head in nearly game-long bouts of apoplectic rage. When a call goes against the Hawks, Hubie erupts from his chair at the head of the bench and storms toward the offending referee like a bouncer going after an unruly drunk. “What kind of an asshole call is that?” he shrieks. After a string of bad breaks or blown plays, Hubie tromps to the end of the bench, squats down in a catcher’s crouch, lectures whatever Hawk happens to be perched there, springs again to his feet, covers his head with both bands, and walks back to his seat moaning, “Oh, Jesus Christ. Oh, Jesus Christ Almighty.” Hubie’s time-outs are legendary, and if he’s especially angry, he summons his charges into a circle around him near the center of the court. But even a wall of seven-foot-tall athletes cannot muffle Hubie’s Jersey-shore croak. “What the hell’s wrong with you?” he screams. “We’ve been down the court eleven times and got only two good shots.” Hunched over a miniature magnetic basketball court on which he moves pill-sized metal discs representing the players, Hubie raves relentlessly about flaws in the team’s offensive execution. Glancing up, he starts in on guard Eddie Johnson. “Christ, I’m telling you, Eddie, that you better get your shit together,” he screams. “The ball is precious, but you go one-on-one with three guys on you. Christ. And your defense is abominable.” He levels Johnson with a withering gaze. When the player attempts to interject, Brown cuts him off. “You’re out. I gotta get somebody who can play.” Johnson again tries to counter the charges, but Brown barks, “Hey, am I talking to you in a foreign language? Didn’t you hear what I just said?” His face blotched with angry red patches, his centurion-style gray hair drenched with sweat, Hubie heaps abuse on nearly every Hawk before the scorer’s horn finally blasts to signal a return to action.

In a profession known for its hair-trigger tempers and blue utterances, Hubie has managed to achieve notoriety not only because of his blistering attacks on referees and players, but because he is willing to go one-on-one with fans as well. It is almost a cliche that professional basketball is life’s only niche in which a short white man can call ten leviathan blacks “sons of bitches” and escape with his hide unscathed; but Hubie approaches the sport as if it also gave him carte blanche to dress down obnoxious devotees in the most hostile of coliseums. If a crowd rides Hubie, he retaliates by spinning around viciously, picking out one of his loudest detractors, pointing at him and yelling, “Do you want to coach this team, Jack? If you do, get down here. If you don’t, shut up.”

Roaring through the season like a mean, late summer tempest, Hubie gives every impression that he is completely out of control during Hawks games. He appears to be merely a tyrannical blowhard whose main goal is to coerce players by intimidating them. But that is only a part of Hubie Brown. What is significant about the coach is not that he behaves like some South American despot railing against a revolutionary junta but that his fiery techniques are only the smoking tip of a coldly rational iceberg. In spite of his game-time pyrotechnics, he is the most glacially methodical coach in basketball. As a result, the Hawks are not so much a team as a ruthlessly directed juggernaut. At times, they seem to function rather than to play. They are meticulously choreographed; Brown calls each of the Hawks’ offensive and defensive plays and will not tolerate any deviation from his directives. Just how integral Brown is to the Hawks is readily apparent; more than any other professional team, the Hawks clearly reflect their coach—not just in their highly synchronized playing style but in their punishingly aggressive zeal.

Brown’s success as the Hawks’ coach is enviable. When he accepted the Atlanta job in 1976, the Hawks were perhaps the worst team in professional basketball. During the previous season, they had won only twenty-nine games while losing fifty-three. Before coming to Atlanta, Brown had coached the Colonels of the now defunct American Basketball Association to a league championship in 1975 and to the playoffs in 1976. Though the Hawks suffered a mediocre season during Brown’s first year in Atlanta, he led them to the National Basketball Association playoffs in 1978. In 1979, the Hawks posted their first winning record in five years and nearly upset the powerful Washington Bullets in the semi-finals of the playoffs. By late November of the 1979-80 season, when Brown signed a five-year contract that will earn him around $150,000 per annum, the team was at the top of the Central Division and had won thirteen games and lost only seven.

In Brown’s three years as the Atlanta coach, he has taken a group of athletes, none of whom are widely acknowledged as stars, and molded them into a menacing machine. That Brown at times treats his players like the cogs and bolts of some inhuman basketball mechanism doesn’t worry him. “This is a very cold business,” he says. “It’s either me or them. When my head is on the block, don’t think they’re going to step up and talk about what a great friend I’ve been or what a warm heart I have. There’s no love in the pros. It’s my job to strain their talent until they cry out for mercy. That’s what I’m paid to do. And I never have to worry about looking in the mirror in the morning and wondering if I’ve done my job.”

On a Monday morning early in the season, the Hawks are clustered around the baskets of the Morehouse College gym throwing up trick shots and bantering with one another when Brown slips onto the court and walks purposefully toward the jump-ball circle. Silently studying several sheets of statistics, the coach is oblivious to the action around him. When he reaches the middle of the court, he stops, tilts his head back imperiously, and stares toward several of the players, who are casually arching up jump shots. Within ten seconds all of the Hawks have tossed their basketballs aside and are rushing obediently toward the center of the court to form a tight ring around him.

Turning his hard, hazel eyes on forwards John Drew and Dan Roundfield, the coach purses his lips in disgust and snorts disdainfully, “When I pick up the stats and you’ve got two defensive rebounds, and you’ve got three for the whole game, then I know something is wrong. We should have beaten Houston, Boston, and San Antonio, but how can we hope to when you two are incapable of understanding the basics.” Brown’s face, usually marblelike and composed, fires up like a kiln. With his chin stuck out, his lips pulled back in perfect mimicry of an attack dog, and his eyes fixed like gimlets on his audience, he is completely cowing. “Should,” he repeats harshly, “is a bullshit word. It’s a bullshit word.”

After searching furiously through the handful of papers he clutches as if they were the Ten Commandments, Brown steps toward Drew, the Hawks’ leading scorer and the one player whose name is often in the limelight. “When a man calls you a star,” the coach says patronizingly, “you are supposed to be able to pass. You are supposed to be able to dribble. You are supposed to be able to rebound. You are supposed to be able to score.” Halting abruptly, Brown jerks in a long breath and roars, “Not just score. Not just score. Not just score.”

For the next ten minutes, while constantly referring to statistics pulled from his ream of data about the Hawks’ previous games, Brown bellows and bawls like an unhinged drill sergeant. Brown and his assistant, Michael Fratello, convert so many aspects of a Hawks game into percentages and numbers that at times the coach seems less like a mentor than a sports demographer. He often computes rather than judges a player’s value. Statistics reveal just how faithfully the Hawks are complying with “the system,” Brown’s highly orchestrated playing method. The system is the functional outgrowth of what Brown refers to as “the philosophy.” The philosophy is a more nebulous part of “the total picture,” but, says the coach, it is the very foundation of success. Brown realizes that he can’t convert all of his players to the philosophy, but if an athlete cannot at least adapt to the system he is, in Brown’s mind, “not good people,” and he is traded.

After methodically recounting the various figures that reveal the Hawks’ pitiful rebounding, lapses in defense, paucity of passing, and shortage of fast breaks, Brown hones in on what he and most other coaches believe to be the Achilles’ heel of every professional team—the selfishness of players. Brown waxes more vociferously on player egotism than on almost any other topic.

Mike Fratello is Brown’s most trusted adjutant. Together, they are like two combative cocks lording over a barnyard of mammoths. With their heads close, their expressions intent, they outline the day’s practice, a non-stop session that will be run with the precision of an engine.

“You want to know why Boston beat us?” he squawks. “It’s because they have people who pass. They have guys who are unselfish. But not us. Isn’t it amazing that we don’t have five guys who can play our defense and make the traps? For Christ’s sake, isn’t it amazing how soft we are? By Wednesday, we’re gonna have five guys who can play. I don’t care who they are.”

Clearing his throat, Brown extends both hands into the middle of the huddle; the eleven team members grab them, in unison, and spread out to begin their warm-up drills. Meanwhile, Brown confers with Fratello, a diminutive, curly-haired Jerseyite who, like the Hawks’ other assistant, Brendan Suhr, has known Brown since high school. Fratello is Brown’s most trusted adjutant. Together, they are like two combative cocks lording over a barnyard of mammoths. With their heads close, their expressions intent, they outline the day’s practice, a non-stop session that will be run with the precision of an engine. To Hawks fans, Fratello is known as “Baby Hubie.”

Watching a Hawks practice is akin to observing a watchmaker assemble the parts of a fine chronometer. It is at the same time like seeing a straw boss put a road crew through a grueling morning of hard labor. The Hawks drill relentlessly on every part of their complicated offenses and defenses and on their opponents’ plays as well. Hovering around the periphery of the court like a raptor, Brown shouts out seemingly abstruse terms, colors, and numbers that signal the players to concentrate on their full-court press or their fast break or their barely disguised illegal zone defenses. The team uses some of the most intricate plays in basketball, and for a player, a Hawks practice is more like a dress rehearsal than a warm-up session. Brown sees the basketball court as a ninety-four-by-fifty-foot grid that, if he spaces his players correctly, can be totally controlled. For Brown, control is the only end, the ultimate reward. As the Hawks rush through their variable plays, the coach screams signals like a traffic cop:

“Get to the spot.”

“Find the lane.”

“Get the rotation right.”

While athletic talent is important to Brown, play execution is paramount. “We don’t have a team that can overpower the best teams in the league,” he often says. “We’re fragile. So what we do is try to have a lot of set plays with options that we know will free people for good shots. We simply can’t physically beat anybody.” The Hawks are the antithesis of a championship team like the New York Knicks of the mid-1970s, a team that featured Willis Reed, Walt Frazier, and Earl “The Pearl” Monroe in the same line-up—all talented basketball artists who demanded great leeway in order to play well. Instead, Brown’s team hearkens back to the Boston Celtics of the early 1960s, probably the most disciplined team in the annals of professional basketball. And the most successful. “Our people,” says Brown “have to be completely subservient to my goals. That’s it.”

As the Hawks run through a fast-break drill, Terry Furlow lopes off the court grumbling to himself. Earlier in the morning, Brown had assigned Furlow to a new position.

“They’re gonna have to pay me more money to play this way,” Furlow mutters as he crosses the sideline.

From across the court, Brown rushes toward the player shrieking, “Jesus Christ. Jesus F. Christ. If you don’t like it here, just get your ass out. Get out.”

A minute later, as Furlow runs through the same drill, he pauses momentarily near the half-court line and dribbles the ball listlessly. “Hey, big shot,” Brown cries, “will you give up the ball? Do you know how to pass it?”

Within seconds, Furlow drives toward the basket, fakes a shot, and throws a bad pass that bounces out of bounds. “What in the name of Christ is that?” Brown screams. Furlow shakes his head and glares at the floor.

He drops the expletive in at the end and beginning of almost everything he says in the same way that preachers in gulch-side tarpaper churches tag “Jesus” onto every admonition.

A Hawks practice never winds down. It simply ends. After running drill upon drill, Brown finally calls the session off and leads his team down a dimly lit flight of stairs to a grim cinderblock classroom. The players fold themselves into tiny school desks while Brown storms to the blackboard and writes one word: “Soft.” To Brown, people who are soft are selfish, inept, lazy, and worse. “Everybody in the NBA is soft to begin with,” he says. “They come here spoiled. They’ve been the star in high school and college, and they are soft. It’s my job to harden them.” For ten minutes, Brown ricochets around the room like an atomic particle in a reaction chamber. Screaming and screeching about the team’s weaknesses, he sermonizes about the previous game. “They have to understand why they lost the last one so they won’t make the same mistakes again,” he contends. Brown can be righteous and obscene in the same breath. His constant use of the four-letter obscenity for intercourse is less foul than it is sanctimonious. He drops the expletive in at the end and beginning of almost everything he says in the same way that preachers in gulch-side tarpaper churches tag “Jesus” onto every admonition. His exhortation finally climaxes in a crescendo of pious fury about the Hawks’ lack of discipline, aggressiveness, and intensity. Shrieking so loudly that his voice cracks, he dashes a piece of chalk into its tray, storms out of the college classroom, and zips down the hall toward the Morehouse bowling alley. There he corrals his nine-year-old son, and for a second they watch a group of students clustered around the long hardwood tongue of the lane. Briefly, Brown’s bellicosity subsides. He smiles at the boy, puts his arm around him, and they walk up the stairs.

Later that afternoon, clad in a white Hawks T-shirt. and a red team windbreaker, Brown traipses down a skylit hallway of the Sporting Club—a plush, northside spa—toward its wood-paneled bar. The John L. Sullivan Bar, a dimly lit retreat hung with ersatz boxing prints suggesting a New York City athletic club, is familiar to the Hawks’ coach; Brown spends much of his spare time at the Sporting Club. Immediately after practice, he rushed to the club’s gym to film a commercial aimed at attracting new members. Now, as he pulls up a chair at a comer table and orders two happy-hour Bloody Marys, he chortles, “This is a great place. Best place like it in town.” The Sporting Club offers one of those private havens that are the privilege of the nouveau riche; it reminds them of how far they have climbed. Like most of the trappings of Brown’s life now, the club is comfortable. Brown lives with his son, three daughters, and wife Claire in a handsome five-bedroom house in the far reaches of Dunwoody. It is a spacious, tastefully decorated house with book-lined shelves and cases of sports memorabilia—all symbols of Brown’s success. At times, the amenities of Brown’s club and home must seem unreal, especially in light of the place where he was reared. Brown enjoys the rewards of his success, but he talks constantly of his past, saying that it is the key to understanding him.

Hubie Brown grew up in a small, four-unit apartment building in a rough-and-tumble section of Elizabeth, New Jersey, one of many tough port towns squeezed between New York and Philadelphia on the Jersey shore. He was an only child, and his father, Charlie Brown—a foreman at the Kearny Shipyards—spent most of his free time teaching Hubie how to play baseball. Charlie and his son passed long Saturday afternoons in an Elizabeth park with a bat and a bucket of taped-up balls. Charlie pitched to Hubie until the sun went down. and the next morning—soon after Hubie returned home from nine o’clock mass—the two caught a train for Penn Station in New York and then took the subway to either Yankee Stadium or the Polo Grounds, home of the New York Giants. They always arrived at the park long before batting practice began, and bought $1.75 tickets for seats along one of the foul lines. Throughout the game Charlie would lecture his son about the sacrifices ball players made to get into the Majors. Charlie Brown wanted his son to play professional baseball, and he drilled him incessantly, sometimes ruthlessly. As a boy, whenever Hubie suffered a hitless night during American Legion baseball games, his father raged at him. “He was a very demanding man,” Brown remembers. “My wife, who’s very bright, thinks I now have a great ability to punish myself for losses because of the way my father punished me for the times I played badly as a child. I don’t know about that, but it is probably the subconscious reason why I really hate to lose.”

The Browns never had much money; they had no telephone or car, and sports was their only form of recreation. They lived in a hard, Irish Catholic neighborhood of working class families. By the time Hubie was in grade school, he had taken a job serving 6:30 mass every morning at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Each night, he hung out on the streets where he learned how to fight and cuss and fend off bullies by bullying back. Between the relentless urgings of his father and the street survival instincts picked up in corner tussles, Hubie was already a brutal competitor by the time he entered high school.

“The really great thing about my childhood,” Brown recalls as he slumps back into his chair and pulls the straws from his drinks, “is that I had great coaches who drove me.” Since 1947, when Brown was the catcher on an undefeated St. Mary’s grammar school baseball team that won the New Jersey state championship, he has usually played for victorious teams. But not surprisingly, he was never spoiled by success—his father would not allow it, and neither would circumstances. When Brown was in the eighth grade, the Kearny Shipyards shut down, and his father lost his job. For nine disheartening months, Charlie, as Brown called him, stood in unemployment lines. By the time Hubie entered his freshman year, his dad had taken a job as janitor at St. Elizabeth’s High where Hubie would be a star in football, basketball, and baseball before earning a dual basketball and baseball scholarship to Niagara University.

During the year that his father was out of work, Hubie watched the family plummet to near destitution. His father had always preached to him that if he worked hard enough, he would succeed, but Brown began to tell himself that it didn’t matter how hard he worked if he lost control of his life. A man who has observed Brown closely for several years says, “Hubie comes from a very brutal world where jobs were tough to get. He remembers that. He identifies with that, because he still lives in a brutal world. Coaches have no security. Deep in his heart, I think it really nags him. I think that’s exactly why he’s so obsessed with trying to control everything about his basketball team and every minute of a game. He wants to have his hand on every single lever that could possibly affect his life, because he remembers when his father couldn’t.”

Unlike most professional coaches, men who were either pro players or highly successful college coaches, Brown came in the back door by coaching at high schools.

At Niagara University, Brown played guard for the school’s great mid-1950s basketball teams, which featured such players as Larry Costello, later a National Basketball Association star, and Charlie Hoxie, the premier Harlem Globetrotter of the early 1960s. Hubie’s father could not afford to travel to the games, but told him to pick out an old man in the crowd and imagine that he had to please that man as if he were his father. Brown still observes the ritual. His father died before seeing his son coach in the pros, but when Brown first took his Kentucky team to the playoffs, two friends bought an empty seat across from the Colonels’ bench and told Brown that it was for his dad. While Brown was a talented athlete, his basketball playing days ended after college when he decided he was not talented enough to play professional baseball or basketball. He decided the would coach instead.

Unlike most professional coaches, men who were either pro players or highly successful college coaches, Brown came in the back door by coaching at high schools. One of his first jobs was at Fair Lawn High in Fair Lawn, New Jersey, where in his initial season his team won just two games, and his wife had difficulty finding anyone to sit with her in the grandstands. But in two years, Brown took the school to a state championship. Brown got his first real break in coaching in 1967 when he took an assistant’s job at William and Mary College; the next year, he took a similar position at Duke University. While in North Carolina, Brown’s college teammate Larry Costello was named head coach of the Milwaukee Bucks and offered Brown an assistantship there. It was the big break for which Brown had been angling. After three years in Milwaukee, Brown moved on to the Kentucky job; two years later, he came to Atlanta.

Sometime during those hard, grinding high school years when his triumphs extended no further than the local newspaper, Brown figured out that to get where his ambition was driving him he needed more than just brass and moxie. An economics major as an undergraduate student and an education major in graduate school, Brown had been exposed to various systemized, goal-oriented approaches to “making it.” Slowly, he began to develop his own philosophy and system. His fanaticism about three-year, five-prong programs has come to resemble that of the Soviet government. His basic formula is not unlike any Dale Carnegie “self help” system, but he has broken it down into so many quantitative hierarchies that it totally pervades his life and the way he coaches the Hawks.

His glass empty, Brown orders a cup of coffee. It has been a long day, and he has a long evening ahead of him. He and Fratello are in the final stages of editing a basketball coaching pamphlet. Aside from coaching the Hawks, Brown appears at numerous basketball clinics every year and is one of the highest paid tutors of the game in the country. During the spring and summer, he is constantly flying to Northeastern cities where he speaks about the sport; usually, his lectures dwell on his system and his philosophy. Not only does Brown proselytize about his method to other coaches, he is often on the corporate self-help circuit, speaking to companies like Aetna Life Insurance and IBM about applying his coaching wisdom to the big game of life.

Setting aside his coffee, Brown grabs his left index finger with his right hand and exclaims, “The whole thing finally can be broken down to five things. It’s how I coach the Hawks and it’s what I tell businesses. You could coach baseball with this system. Or football. It’s very adaptive.

“The first thing is that you’ve got to be totally organized with your goals—daily, weekly, and monthly. That’s why we keep such careful records on everything the Hawks do.

“The second thing is that you’ve gotta have a total philosophy. By that, I mean that in basketball you’ve gotta understand the game so well that you have a sound system. A sound system is the hallmark of every good coach. It’s why a great coach can take a mediocre team against a talented bunch of morons and he can ‘X and 0’ them to death.”

Counting down quickly, Brown adds, “The third thing you must have is discipline. You can treat a player anyway you want to as long as it’s fair and it teaches him something. By the time they get to the pros, they don’t want love. Hell, they’re making an average of $137,000 a year.

“The fourth thing is good people, people who will be subservient to the team. The big problem with pro ball today is urban blacks. Now, Southern blacks are all right, but these urban kids who come off the streets think the sport is just run-and-gun and dunk-and-shoot, and they’re so damn cocky. They just won’t fit in.

“The final thing you’ve got to have,” Hubie adds, “is style. We play like blue-collar workers. We bring our lunch pails with us and we wear you out. We’re a ninety-four-foot team and we press and fast break and we control everything we can.”

While Brown’s systemized approach sounds no different from any other general form for solving a problem, he uses it as an umbrella for the dozens of secondary systems that he religiously employs in his coaching. He can categorIze and subcategorize almost every element of the Hawks’ playing style and plug them all back into the “total picture” like a telephone switchboard operator. He believes in the system like some men believe in God.

Pushing himself up from the table, Brown picks up the check, pays it, and walks out of the bar. It is already dark, and he has a thirty-minute drive home.

During Brown’s difficult climb to a head coaching job in the pros, he made his share of enemies. Shortly before comIng to Atlanta, Brown was contacted by the owner of the Milwaukee Bucks and asked if he’d be interested in returning to the team as head coach. At the time, Larry Costello was still coaching the Bucks, and Brown contends that he emphatically said he would not consider taking the job as long as Costello had it. Shortly after Brown talked with the Bucks’ owner, the Milwaukee Journal printed a series of articles implying that Brown was actually jockeying to take Costello’s job. “That was just fiction,” says Brown. “It was so far from the truth. It ruined a great friendship. It’s probably the worst thing that ever happened to me in sports.” Costello is still bitter about the episode, claiming that Brown was vying for his job. After Brown took the coaching position in Atlanta, Costello resigned; he now coaches a professional women’s team. “I don’t want to get into it again,” says Costello. “But I will say that Hubie is a real rotten apple. A horrible person. He’ll do what he wants to get what he wants.”

The fanatical control that Brown exercises over the Hawks leaves little room for contentious employees in Atlanta management. Mike Storen, formerly commissioner of the American Basketball Association and briefly general manager of the Hawks, contends that Brown consciously set out to have him fired from the Atlanta job. “He’s a sick man,” says Storen. “He wants to control everything, and if you get in his way, he’ll get you. He plots. He schemes. It’s all very deliberate. He ruined my career in basketball.” Hawks owner Ted Turner dismissed Storen in 1978; since then Storen has filed a $300,000 suit against the Hawks. During Storen’s short tenure with the team, he and Brown fought over the future of several players and the general style in which the Hawks would be managed. “I thought it would all work out,” says Storen, “but Hubie decided he had to get me out of the way, and he got it done.” Brown counters, “Storen pulled so much shit while he had that job that Ted had to can him.” Shortly before Turner deposed the general manager, Storen asked an Omni technician to bug Brown’s office phone. The workman refused; the next day Storen was fired.

While Brown has had his share of disputes with players, he has made surprisingly few enemies among athletes he has coached. When Brown traded Lou Hudson, Atlanta’s only bona fide superstar, to the Los Angeles Lakers in 1978, the All Star guard protested. He had played for the Hawks for ten years and was still one of the game’s finest pure shooters. “Sure it hurt to leave Atlanta,” says Hudson, “but I don’t blame Hubie. He did what he thought was right. He’s a great coach. No one knows more about the game. No one is better prepared. In Los Angeles, I played for Jerry West. who is a much nicer man. But I’ve got to say that Hubie’s a better coach.”

“Hubie’s a very intense man whose entire happiness revolves around winning. It’s the whole thing with him. He’s seen that the NBA is a war and that you can’t win with kid gloves on.”

While most of the Hawks admire Brown’s regimented approach to the game, few of them will talk publicly about what it is like to play for a coach who berates them constantly. They cite Brown’s propensity for fining players who speak derogatorily about the team. Says one player, “I have to have all my creative outlets elsewhere. I’m just part of a system here.” Another adds, “It’s okay if you’re a machine, but if you’re a human being, he can beat you down.”

Tom McMillen, the Hawks’ reserve center, says, “Hubie’s a very intense man whose entire happiness revolves around winning. It’s the whole thing with him. He’s seen that the NBA is a war and that you can’t win with kid gloves on. He has to be autocratic to triumph. Now there are many players in the league who are so egocentric that they could never play for him. They’d clash with him. But I respect what he’s done very much. His system, while rigid, is fair and it works. The way he has it set up, we’re all rewarded for our efforts. He plays ten of us each quarter, and we all get our good shots. The difficult thing is that losing is such anathema to Hubie that he tries very hard to make us miserable too. He just doesn’t want us to get used to losing. I don’t blame him, but it’s hard sometimes.”

Nowhere is Brown’s urge to control his life better illustrated than in his relationships with reporters. Brown’s press conferences are akin to papal appearances. After a game, he enters the press room clutching a beer, gazing silently at the mass of journalists who are waiting for some tidbit about the team. After staring at them briefly, he issues a perfect report on the contest, a state-of-the-game speech replete with esoteric statistics. It spills from his lips like a computer printout. He has a near photographic memory of games and can pinpoint every key shot or block. After a ten-minute spiel, he often concludes with the warning, “Now I don’t want any stupid questions.” He berates journalists who do broach ignorant queries by replying mockingly, “Now, if you’d ever seen a pro game before, you wouldn’t be asking that.”

Among sportswriters, there are very definite pro-Brown and anti-Brown camps. The situation is illustrated graphically by the way Atlanta’s two daily newspapers cover the team. Darrell Simmons, of the Journal is, in Brown’s estimation, “a great writer, a fine journalist, a man who understands the sport.” George Cunningham, the Constitution reporter covering the Hawks, is, says Brown, “a truly sick man who is out to destroy pro basketball in Atlanta. He is the most dangerous threat to our team.” At a booster club meeting at the Atlanta Hilton in September, Brown launched into a lengthy diatribe against Cunningham, accusing the journalist of “trying to ruin us.” Cunningham’s coverage of the Hawks often highlights the play of John Drew and Terry Furlow, the team’s most explosive scorers and the two players Brown rides hardest during practices. Simmons usually writes about “team efforts.” Cunningham almost never quotes Brown, while Simmons quotes him extensively. Cunningham counters Brown’s criticism by saying, “Hubie’s a great coach, but he’s such a horrible egomaniac that he can’t stand any criticism, and he can’t stand anyone else getting any publicity. The reason he hates me is that I’m the only media voice in town who will criticize him at all. The rest might as well be on the Hawks’ payroll. They follow the party line.”

It is Friday night in the crowded Spectrum, the home of the Philadelphia ’76ers, one of the most awesomely talented teams in basketball. With Julius Erving, “Dr. J.,” at forward and a massive locomotive of a center named Darryl Dawkins, whose slam-dunk shots shatter backboards and whose 250-pound body has flattened more than a few wiry defenders, the ’76ers are star-studded opponents. The Spectrum crowd is unusually unruly. Thursday marked the world premiere of The Fish that Saved Pittsburgh, a bit of bad basketball cinema staring Erving, and the team organist is cranking out the disco theme music from the show while the arena’s patrons are screaming for blood, preferably Brown’s. Three nights earlier, the Hawks had handed the previously undefeated Philadelphia team its first loss of the year; ’76ers enthusiasts do not want to see their team’s record drop from “8 and 0,” to “8 and 1,” to “8 and 2”—all at the hands of the unsung Hawks. As Brown follows the team onto the court, a chorus of boos wafts down to greet him. “Better cool it tonight, Hubie,” one shrieks. “You’re crazy, Hubie.” Brown’s detractors are located both behind the bench and beneath the Hawks’ basket, and as he surveys the scene, he realizes that for an entire evening he’ll be caught in a cross fire. Before the game starts, he crouches down and pulls out a small package containing a painting of Jesus and two Catholic medals. His father gave them to him long ago. Kneeling, he kisses the picture and tucks it into a pocket.

It is a desultory first half in which defense dominates the game. Neither team can muster any scoring. Hubie stomps up and down the sideline, Fratello following as if attached by strings. During a game, Fratello constantly suggests plays and options that might get the Hawks some baskets. Fratello’s running charts on a game are so intricate that he is able to inform Brown immediately which plays are working most productively and which defenses are the most stingy. But tonight, very few of Brown’s orchestrated plays are functioning. Brown becomes so despondent that he simply sits on the bench, his head cradled in both hands, as if to watch is too painful. The first half is out of control. Occasionally he rises to his feet and screams to center Tree Rollins, “Be big, Tree.” During one time-out he accuses Eddie Johnson, Dan Roundfield, and John Drew of being “the three stooges of basketball” and says that if they keep playing stupidly he won’t be able to abide seeing them on the court any longer. As he walks into the dressing room at the end of the half with the Hawks trailing 38-33, his face is drawn and tired. He simply shakes his head.

At the start of the second half, something seems to have come over Brown. He is no longer content to sit back. He is up prowling, shifting his shoulders like a boxer. It is a low-scoring game, the kind a coach can control more easily than a run-and-gun contest, the gritty kind of game won by playing the vicious defense and control offense that Brown loves. Even before a minute has elapsed in the half, Brown is up and shrieking at Dan Roundfield, “Jesus Christ, you’re just wasting my time out there. I’m getting you out of the game.” When Brown is coaching aggressively, he is a master of operant conditioning. The most universal negative stimulus for a basketball player is to threaten him with the bench, and as the contest heats up, Brown is screaming constantly:

“One more pass like that, Charlie, and you’re on the bench for the rest of the night.

“For Christ’s sake, John, if you do that again you’re out.

“Jesus, Tree. Why don’t you dunk it? You’re the only center in the pros who can’t stick it in the hole. Jam it in there or you’re through.”

Like an overseer on a galley ship, Brown lashes’ out at whoever appears to be lagging. His gaze is riveted to the court.

In the contest’s last four minutes, Brown is like a chessmaster in a brutal game of speed chess. Bobbing up and down from his seat, touching his fingers to his temples, he screams: “Deny. Deny.” The Hawks are attempting to keep the ’76ers from passing the ball inside for easy shots.

As the Hawks bring the ball down on offense, Brown shrieks, “31.”

As Atlanta drops back on defense, he screams, “Black.”

Darryl Dawkins misses a close shot. and as the Hawks bring the ball back up court they have a slight lead, and Brown yells, “Be tough. Be smart.”

From beneath the Hawks’ basket, fans are screaming, “Shove it, Hubie.” As the team works its offense, John Drew breaks into the open for a good shot, and as he goes up with the ball one of the ’76ers flattens him. Drew crumples to the floor, and Brown rushes onto the court. His face flushed, he is bending over the player when several fans pour onto the court, shooting their middle fingers into the coach’s face. Brown stands his ground, glares, then smiles as the police step between him and the mob. “We beat you three last year. It’ll be four this year,” he barks as two burly officers push the mob back into their seats.

When Eddie Johnson hits a jump shot with three seconds left in the game to put the Hawks ahead for good at 85-81, Brown raises his hands over his head, clutching his fists. The game ends. The Hawks have won, and Brown shouts the only truly affirmative words he’s said all night: “Oh yes. Oh yes.” He is completely joyful, as if this is the only moment of joy, the only time when he has real control.

This story is collected in A Man’s World.

[Featured Image Via Sam Woolley]